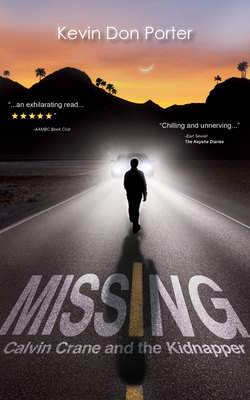

Читать книгу MISSING - Kevin Don Porter - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Nebraska

Grandma Edith was sounding-off again. “Slow down Darn, you’re driving too fast.” Darn this, Darn that. That was how she said Dad’s name. Not Darnell, but a whiny “Darn.” What a nickname. Grandma said it was easier for her to yell “Darn” when she wanted Dad’s attention instead of saying his full name. Calling him Nell for short would’ve been bad enough—but Darn? I knew Grandma got a kick out of it. I did too. Kinda summed up how I felt when I found out she was coming on our summer road trip.

Everything was too fast for her. Slow down, Darn, you’re eating too fast. Slow down, Darn, you’re breathing too fast. Slow down, Darn, you’re slowing down too fast. Me, Cybil, and Solange just sat there squeezing back our laughs ‘til they trickled through like bad diarrhea. It was Dad’s bright idea to invite Grandma on the trip to California in the first place. Now there was no turning back. We were stuck. And the roof of the van wasn’t strong enough to hold her. I checked. Besides, she would never clear any low overpasses.

Dad said we would be hitting North Platte, Nebraska soon. I loved traveling to towns out West. They were the descendants of gold rushes and golden dreams. Of guts and glory. Of cowboys, general stores, and one-room school houses. Of hallowed potato museums and the world’s largest itchy balls of twine.

I had rules for road trips. I called ‘em Calvin’s Code. Number one: If you absolutely must fart, go ahead. But sit on it. A fart starved of oxygen usually suffers a quick death, sparing the slow deaths of those in its vicinity. But in case of emergency, have a cracked window on standby. Number two: If you fart in public when no one’s around, someone will always come from outta nowhere and walk right up to you – guaranteed. Farts are magnets for unwanted company. Just pretend to be as disgusted as they are.

Number three: Morning breath is usually much worse than the night before. So avoid big yawns when you blow out, and don’t leave your mouth uncovered. Number four: Frito feet are very common. So don’t remove your shoes when your feet are especially sweaty. Have a clean pair of socks handy. Number five: When you feel like talking, no one else will want to. And when you don’t want to talk, someone else always will. Finally, number six: People will never agree to do the same thing at the same time.

Case in point: Grandma Edith. Matter fact, I just thought of rule number seven: Never bring Grandma on your road trip. She whined, “Do we really have to stop now, Darn?” Did she have something better to do? Last I checked soaking your dentures and clipping your yellow toenails were not activities. Especially in the close quarters of children who may or may not have nightmares about being chased by chomping teeth and airborne toenails the size of boomerangs.

“Looks like an interesting gift shop coming up, Ma,” Dad said.

“Let’s stop!” I said. “We could find some neat stuff!”

Solange covered my mouth with her grubby hands. “Don’t stop, Dad.”

I fist-pumped as the van slowed down and we turned off the interstate. We pulled up to the gift shop and jumped out. Grandma caved and came in too. She didn’t wanna be stuck out in that heat. I hadn’t stretched my legs since the McDonald’s about a thousand miles ago. Felt good to be out of the van. Still felt like I was moving though.

The building looked like it was made from logs and sticks. Fake soldiers perched on the rooftop holding rifles stopped me in my tracks before I realized they weren’t real. A man hung over the edge with an arrow in his butt while more soldiers stood watch in two towers at the front corners of the building – like we had just walked into the middle of battle. If the soldiers had done their jobs maybe their poor friend wouldn’ta become a shish kabob. “Fort Cody Trading Post. What’s in there, Dad?”

“That’s why we stopped.”

The doorbell jingled behind us, and the little stick-front building opened up into an emporium of western chotchkies. The metallic aroma of leather and animal skins mingled with spicy cedar-wood slices that had been made into clocks and wooden cowboy figurines. The smell of Indian-made leather wallets and wooden trinkets. The scent of the West.

My jaw dropped. A wall of miniature guns. Little guns like pistols, ones like shotguns. And they came with tiny caps for bullets. I scooped handfuls of quartz and mica. “Dad, look at all this stuff!” Bags of fool’s gold. Piles of arrowheads tied to wooden handles. I could get used to the West.

This place was a history book where I could try everything on. It let me live in another time, be another person. I wore an Indian headdress that sprouted with long, colorful feathers and caught myself in the mirror. I’d always heard about Indians at school. How they were defeated by American soldiers. How they live on places called Reservations. But every time I thought about it I got that same strange feeling as when I saw lions in a cage at the zoo.

Grandma Edith was standing behind me. “You look just like your great-grandfather. He was part Indian you know.”

My eyes lit up brighter than two nuggets of fool’s gold. I turned around. “Really?”

“Yup,” Grandma nodded, propping her hands on her cane. “Don’t know what tribe though. But he was a half-breed.”

I stared in the mirror. “Wow.” I wasn’t just black anymore. I was black and Indian. Indiak. No, Blindian. I guess that connection I felt with the West wasn’t just in my mind. It was in my veins.

We piled back into the van with our bags of stuff, and Dad turned the key in the ignition. “Uh-oh,” he said. “Won’t start.” He hopped out and lifted the hood.

Grandma Edith put her hand on her chest. “Oh, Lord, it’s a sign,” she said, shaking her cottony-white hair.

Cybil said, “A sign of what, Grandma?”

“Maybe we shouldn’t have come on this trip. Maybe we should turn around and go back home.”

Cybil sucked her teeth. “We can’t, Grandma. I have to be at Malinda’s wedding. I’m a bridesmaid. Remember?”

Mama looked back at Grandma. “Besides, Edith, it’s a little too late for that. We’re ninety million miles from home. We’re in Nebraska for goodness sakes.”

Maybe Grandma should try walking back. She’d get home. At some point.

Dad jumped in and tried it again. This time the van revved right up. “Everything’s good. Loose connection to the battery post, that’s all.”

“See, Edith,” Mama said. “You got yourself all worked up for nothing. Everything’s gonna be just fine.”

We headed to the Quimby’s house. Friends of Dad’s who owned a farm. We drove and drove, seemed like forever. There were cornfields everywhere. I had never seen so many cornrows in my life, not since Cybil and Solange’s nappy heads. Rows and rows and rows that seemed to spring into motion like a flipbook as we drove by. The stalks were so tall. Way taller than me. What if I got lost in there? What if somebody dropped me right into the middle of one of those fields, and I had to find my way out? And what if it was dark? I would be terrified. Especially if they had a scarecrow. Good thing I had that cap gun Mama bought me back at the trading post.

I hit Solange on the shoulder. “You got the Children of the Corn touch! Shields!”

Solange hit Cybil. “You got the corn touch! Shields, force fields!”

Cybil hit me.

“Too late,” I said. “Already claimed shields.” She went for Solange again.

Solange put up her hand. “Shields force fields for life!”

It was night time when we got to the Quimby house. They had more fields of corn. We turned off the road onto a long gravel driveway. We drove past the cornfields until I saw a big white house and a little trailer off to the side. “What do we do now, Dad? Isn’t it too late to knock on the door?”

“We wait ‘til morning,” he said, leaning back in the front seat and closing his eyes.

Everybody else was asleep, but I stared out into the cornfields. They weren’t far away. We had to sit here all night and wait for morning. The back windows and the dome were open, and I could hear the screeching crickets. Every once in a while, footsteps. It’s a wonder how the earth is never completely quiet. Something in nature is always humming like a machine. Going about whatever it is that it’s supposed to do. There could be anything out in those fields. If I lived on a farm, I would be too scared to go out at night. I didn’t know how these people did it. Mama grew up on a farm, had an outhouse and everything. I couldn’t imagine heading outside at night to use the bathroom and bumping into the Boogeyman on the way. Not that I believed in the Boogeyman, I’m just saying. I had to pee. I had to go so bad I could feel it in my cheeks. You know how you get that tingling in your jaw?

“Whoever is doing that shaking, stop it,” Dad mumbled.

I kept still. But not for long. Felt like I was gonna burst. “I gotta pee.”

“Well, go do it.”

Something could be out there in those cornfields. If I said a prayer the Lord would protect me. Our Father, who art in Heaven…

“Calvin, go pee,” Dad said.

He messed me up. “I will.” I tried to keep my leg still. Our Father, who art in Heaven, hallowed be Thy name...

“Well, what’re you waiting for? The second coming?”

Just let me finish. I had to start over again now. Our Father, who art in Heaven…Give us this day….I was almost done. For Thine is the kingdom, the power…

“Calvin!”

Shoot! Now I had to start all over again. I couldn’t hold it any longer. I jumped up, climbed over Grandma, and jumped out. I went to a tree behind the van, peed, and came back. I had to finish that prayer. This time I finally got to the end. I started to drift off to sleep when I realized I had forgotten about being scared while I was out there. Guess the prayer worked.

When I woke up it was freezing. As hot as it got during the day you would think it would be a halfway decent temperature in the morning, but no. I didn’t have any cover either. Cybil and Solange were hogging it all. Talk about pigs in a blanket. Grandma was stretched across the two seats in front of us. I was yanking on the cover and…Bang! Bang! Bang! I almost jumped out the bed. I peeked between the curtains and saw a heavy-set white lady standing outside.

A white lady? I guess the people Dad knew had moved? Here we were camping out on their front lawn, waiting ‘til morning to surprise them, and they didn’t even live here anymore? I was so embarrassed. Why didn’t Dad call first to make sure they still lived here? I know these white people were about ready to call the police! I shook Cybil and Solange. “Get up, y’all!”

We were in trouble now. Dad jumped out the front. I could hear high-pitched voices.

And, laughter. Who was laughing? They both were. I peeked out the curtains again, and Dad and the lady were hugging. Now Mama was hugging her! Dad actually knew these people. White people who would let us camp out on their front lawn? I was scrambling to brush my hair and put on my shoes when Dad flung the side door open and held out his hand. “Dolores, this is my mother, Edith,” he said. Grandma dipped her head and smiled. Luckily she still had her teeth in.

Then, in her real proper voice, Grandma said, “Nice to meet you, darling,” holding out her hand. She could really turn it on when she wanted.

Cybil and Solange were scrambling like mad to try not to look like a couple of wild banshees with sleep in their eyes and dribble down their cheeks, but too late.

“And these are the kids,” Dad said.

We smiled and waved.

The woman had rosy cheeks and a warm smile. Funny how differently people looked once you knew where they stood. “Y’all slept in the van all night?” she squeaked. “Why didn’t ya just come knock on the door? We got plenty spare rooms.” She took us inside.

I was excited. A white person’s house! I mean, I been in Billie’s house before (he’s my friend back at home). But that was different. He was white, but I always knew he didn’t represent the true white people. He was the trailer park version. Like the imitation cereals Dad would bring home thinking we wouldn’t know the difference. Dolores Quimby was brand name.

The house was just like I thought it would be inside. Like I’d seen on TV and at the movies. Big and shiny and clean. Wide open rooms you could just walk through with your arms stretched out wide. Light coming in everywhere. The smell of potpourri. The smell of clean. The kitchen was long and neat and had flowery patterns on the frilly country curtains. I stared at the glass jars lined along the tops of the cabinets. Dolores must’ve read the look in my eyes.

“Those are preserves,” she said. Her cheeks growing even larger.

I looked up at Mama. “Reserves?”

Dolores grabbed a pan that was hanging in the air. “Sometimes when we don’t eat everything we grow, we can preserve them in glass jars, and they’ll last for years. Berries and vegetables and all sorts of things. And when we get hungry, we can go back and eat ‘em when we get good ‘n ready.”

“Won’t they be rotten?” I couldn’t imagine Mama cracking open a dusty bottle of furry old vegetables that were just as old as me and actually having to eat ‘em. I barely wanted to eat the ones she cooked straight from the frozen food section.

“Nope, ‘cause the jar seals nice and tight and keeps all the air out…keeps it nice and fresh and tastin’ good.”

Guess I had to get used to this country way of doing things. I stared up at the ceiling, then leaned over to Mama and whispered, “Why are the pans hanging in the air like that? Is that so roaches won’t get in ‘em?”

* * *

Ms. Dolores, that’s what Mama told us to call her, cooked us a big ol’ country breakfast. I mean big. Fresh biscuits with butter she said she made from cow’s milk. I still can’t understand how that happens. Scrambled eggs Ms. Dolores said were fresh from the chickens…everything was so fresh here. Whatever we ate was just squeezed or just laid or just something. Kinda made me sick thinking about it. About all the animals while I ate. Stuff just falling out of ‘em or being squeezed out of ‘em and us just sitting here waiting to eat it.

Ms. Dolores’s son, Forest, ate breakfast with us, but her husband, Brad, was out of town. Forest. Interesting name. White people’s names were so different. I know we had our Shauntays and Dauntays and Keishas. But they had their Summers and Winters, Aprils and Autumns. I guess Ms. Dolores was staring out at the trees when she came up with the name. Good thing she wasn’t out on the farm looking at a cow or something.

After we ate, Ms. Dolores took us to what she called the Family Room where we all sat and talked. Forest came too. He was about Cybil’s age. Tall and skinny with a head full of dirty blonde. About the same color as Billie’s, except that Billie put the “dirty” in dirty blonde. Forest made the color look clean. He kept swinging his curls out of the way while he talked. White people and their hair. It was so neat watching them. Combing their fingers through it. Twirling it around. Tossing it back and watching it fall perfectly back into place.

The room had gone quiet. Everybody was looking at me. “What’s wrong?”

Dad said, “We’re waiting for an answer.”

I looked around. “To what?”

Dad’s brown eyes grew the size of golf balls. “Forest asked how you liked the Fort Cody Trading Post.”

“Oh, it was great. I brought a gun.” I nodded.

“Bought a gun,” Mama said.

“Yeah.” I nodded.

“That’s cool,” Forest said. “I like that place too.” He looked at Cybil and Solange. “What did y’all get?”

Solange said, “I bought a little Indian doll with a baby on her back. I forgot what they call it. A papoo, or something.”

“It’s called a Pa-poose,” Grandma said, pushing out each syllable. “Y’all kids today don’t know nothing about Indians, but they supposed to be teaching you American history. They only tell you what they want you to know. Buffalo Bill Cody,” she said, like it had put a bad taste in her mouth. “Indians were here first, and the white man pushed ‘em out and they get the monuments.”

I wished I could’ve snatched Grandma Edith’s words from the air with the speed of sound before they reached Ms. Dolores’ and Forest’s ears. That was the kind of thing you think, not say out loud. Why couldn’t Grandma have lost her teeth this morning? I stared down at my lap. My eyeballs were like paperweights. Even the silence in the room had a sound.

I finally peeked up at Ms. Dolores. She smiled and tossed her long, dark brown hair over her shoulders. “My father is half Omaha. I’ve heard that all my life.”

Relief.

* * *

Solange asked Forest, “What’s in that little building over there?”

“It’s a trailer. My grandma’s house.”

I had finally seen a house even smaller than ours back at home. Forest showed us around while his grandmother was out at the grocery store. He said she should be gone for a while so it was okay. The creaky metal screen door bounced behind us. As soon as we stepped in, mothballs, eucalyptus, and Pine Sol hit me like a bully after school. The “old” smell.

The place was stuffy and hot. Forest cracked a window. “Grandma stays so cold all the time. Remind me to close this before we leave,” he said. The narrow hallway was stacked with piles of yellow newspapers and books. Frameless pictures and portraits covered the walls like peeling skin. Made me wanna scratch.

I looked around. “Old people. They hold on to everything.” Forest looked back at me. “My grandmother’s old too,” I said. There was a big black and white portrait of a young woman on the wall. “This your grandmother?”

“Yup,” Forest said.

She must’ve had a big life. Knew a lot of people judging from all the faces on the walls. But something about the tiny trailer seemed like locking the dog in the basement when company came. At the end of the hall in the little living room was a huge flag I didn’t recognize pinned up on the wall. “What’s that?” I asked Forest.

“A flag.”

“I know that, but of what?”

He shrugged. “I dunno. Been there forever.”

Maybe his grandmother was an immigrant. Probably the country she was from.

“Oooh-Oooh,” Cybil and Solange sounded like a pair of owls. It was a bedroom full of dolls. Shelves of ‘em. White dolls with puffy pink cheeks, little red lips, and curly blonde hair. The dresses covered their feet, making ‘em look like little angels in bonnets.

Solange bounced like a basketball. She reached up. “Can I hold one?”

“No!” Forest shouted. “Grandma don’t let nobody touch ‘em. Only she can. If something happened to one --”

The screen door bounced. I froze, hoping it was Ms. Dolores. But slow, dragging footsteps sounded…Please don’t let it be…

Forest said, slow and sorry, “Hi, Grandma.”

Me, Cybil, and Solange looked like The Three Stooges the way we bumped into each other trying to find a hiding place. Maybe we could hide and slide out when she wasn’t looking. But the old woman was in front of us now. She dropped her grocery bag and sounded like somebody had her by the throat. Like a whispering gremlin. “Who are they?”

“Calm down, Grandma. Just some friends from out of town. Visiting Mom. Didn’t you see the brown van outside?”

I reached out to her. “Hello.”

She growled, “What are they doing in my house? You don’t let strangers into my house!”

Forest waved us out, and we didn’t waste no time! Once we got out by the van, we busted out laughing.

* * *

Cybil and Solange were back in the house. Ms. Dolores was showing them how to make peach preserves. I played outside with Forest’s black cat, Midnight. I didn’t know a black cat that wasn’t named Midnight, or Blackie, or Smokey. White people loved them some cats…and dogs. Black people around my way didn’t usually have pets other than goldfish or something else that could be tanked or caged. Guess it would’ve just been one more mouth to feed. I only knew a few that did.

My neighbor, Paula, was one. She had a little black dog named Pepper. At least she got creative with the name. I used to walk him for her. I think it was a he. She was about the only black person on the street with a dog that they actually bought and didn’t just find. I for sure never had a dog or cat, except it was a stray. And then it only hung around as long as I was throwing it bologna. When I ran out, it did too.

I had the plastic seal from a gallon of milk tied to a string. I would throw the string out toward Midnight, and she (I really didn’t know if it was a he or she) would creep up real slow and try to pounce on the seal with her paw. I would yank it away just in time. I did this for almost an hour. Midnight loved it.

Forest came and sat down beside me on a fallen tree trunk. Talk about two bumps on a log. He threw rocks and watched them disappear into the cornfield. He stared down at the ground. “Sorry about that with my grandmother and all.”

“Don’t worry about it. We shouldn’t have been in there in the first place. Plus, it kinda makes up for what my grandma said earlier. So we’re even. What’s wrong with old people anyway?” I tossed the string out to Midnight. Do you think she would’ve been mad if we were white? That’s kinda what I wanted to ask, but I didn’t wanna put Forest on the spot. Maybe his grandmother was just mad ‘cause we were strangers up in her house, that’s all. Old people were particular that way. Still seemed like after Forest explained who we were she could’ve shook my hand.

“So how is it living out here?” I asked.

Forest shrugged and threw another rock into the cornfield. “Okay, I guess.”

“Do the cornfields ever scare you?”

He laughed. “No. Why should they?”

“You never seen Children of The Corn?”

“Calvin, when you get my age, movies like that don’t really get to you. So how’s it living in DC?”

I yanked the plastic cap from Midnight. “I don’t actually live in DC. We just tell people DC because everybody knows where it is. But I live pretty close by in Maryland in a town called Capitol Heights.”

Forest nodded. “So you’re close to all the action.”

“That’s what everybody thinks. It’s okay I guess.” The evening air was cool and damp. I breathed in deep. “I think I would love living out here, though. Except for all the cornfields. And the cows and chickens and preserves and stuff.”

Forest threw his hands up. “Not much left past that.”

“I guess not. Isn’t it something how we end up the way we do? And we don’t have any say about it? Me on the east coast, you out West. Me black, you white. You ever think about that?”

“Not really.”

I smiled.

“What?” Forest asked.

“You never had to. You know what my friend, Billie, told me the day before our trip? That white people out West won’t like me because I’m black.”

Forest threw a rock. “Some friend.”

“Tell me about it.”

“We like you so you know it’s not true.”

“Not all true. But how much?” I could just see Billie’s neck winding like a snake: “Most white people out West won’t like you.” What if he was right? How many was most? I had decided to keep a tally. Write down whatever happened, the good and the bad. I needed to know. It’s really not stupid. The government does it all the time, use numbers to make decisions. Especially about race. The number of blacks and whites in a state. The number of blacks who own homes. The number of whites with a degree. They turn color into numbers. They say age ain’t nothing but a number. Maybe color is too.

Maybe all of ‘em wouldn’t like me, but I would feel better knowing most of ‘em did. Kinda like the President knowing he got elected by more than fifty-one percent. Then maybe it could be the best summer-vacation story in Mrs. Williams’ sixth-grade class. Maybe it could win best summer-vacation story of the school and be featured in the Capitol Heights Gazette like the one last year. Maybe it could change everybody’s minds about everything.

I just wanna be okay.

Stop hiding all the time, stop trying to just get through. Stop being scared somebody’ll call on me. For once, I want to raise my hand.

I looked at Forest. “You never had to think about stuff like that ‘cause it’s never been a problem for you. You never had to wish you were something else because what you were wasn’t good enough. You’re lucky.”

“Because I’m white.”

I nodded. “Things happen for you. People like you. It ain’t your fault. That’s just the way it is.”

“Believe me, everybody doesn’t like me.”

“At least you get the chance to help ‘em decide, instead of them seeing you and already being decided.”

Forest threw another rock. “Somebody decided about the little white girl from Kearny that went missing that everybody’s talking about. What did she do to deserve that?”

“You knew her?”

“No, but some of my friends did. Got everybody around here on edge again.”

I let Midnight get away with the string. “Again?”

“Two other kids went missing back in the spring. Each one was from a state close by. One black boy, one white. Whoever it is don’t discriminate. Each time they went missing they said nobody noticed nothing unusual. No screams. No strange sounds. It’s like the kids just vanished. Whoever it is must’ve blended right in. Looked friendly. Safe.”

“How long she been missing?”

“Almost a week. Could be dead. Could be alive. Could be dragged off to another state by now. Who knows? Everybody’s looking over their shoulders. People don’t wanna let their kids out to play no more. They telling people to watch out for some man they don’t even have a description of. If it even is a man. Alls I’m saying is that little girl is gone, and there’s nothing she did to deserve it.”

I tried to picture the girl and how scared she must’ve been.

“I know you’re on vacation and all, but wherever you go don’t go by yourself. Don’t trust no strangers. Keep your eyes open. He’s out there. Somewhere.”