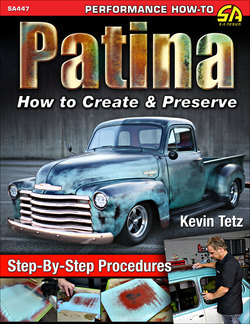

Читать книгу Patina - Kevin Tetz - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT

Perfecting your paint technique by practicing will give you the confidence you need to do an excellent job, regardless of your goals. Even hobby painters make a regular practice out of doing “spray outs” on separate test panels to get a feel for gun settings, color selection, and temperature recommendations, as well as to improve muscle memory.

You need to have a strategy to be comfortable moving into your paint job to achieve the patina of your choice. When you look closely at a worn paint job, you’ll notice that there are several different aged effects that need to be recreated, depending on the area. There can be wear around the driver door, sun damage on the top panels, delamination and rust on lower sections, and abrasive damage and rock chips on the leading edge of some panels.

This late 1960s pickup shows its great natural patina with much of the original color still on the panel. The wear occurs naturally where a driver’s arm would hang out the window. This vehicle doesn’t have an air conditioner, so driving with the window down and using the opening as an armrest would be common.

Aged Effects

A realistic patina job becomes much easier if you break it down into specific sections. We will focus on the main types of patina: wear damage, sun damage, and impact damage. Mimicking these effects takes some consideration, so let’s break it down to three categories.

Wear Damage

One thing to remember is a paint layer is very thin. Most factory paint jobs are only 2.5 mm total thickness, so it stands to reason that the paint can wear through in certain places over time. Certain areas are more susceptible to wear, such as the door handles, scuff plates and rocker panels, the bottom of the door glass opening where someone’s arm may hang over, and even the edges of a hood where it may have been handled opening and closing for decades.

Another common spot to find wear damage is around the ignition key. Wear to a factory single-stage metallic paint job can create an interesting pattern under the bezel. Wear damage can also create a matte finish on a vehicle that was once semigloss. This occurs because as the color is worn away so are the resins that hold the gloss.

A keychain swinging from the dash for 50 years created a distinctive pattern on the paint of this 1966 C10 truck. This is original and very subtle. Sometimes one can accentuate wear like this in the spirit of creating an effect and still maintain realism in the patina.

This 2000 F150 has a badly damaged clearcoat finish. As clearcoat degrades, it turns lighter and becomes chalky white before it completely delaminates. This wear is from the sunlight and UV energy oxidizing the color under the clear, causing it to separate.

Vehicles that have natural patina and worn paint provide clues as to the history of the vehicle. They also give inspiration for age effects to recreate on paint.

Sun Damage

The combination of time and exposure to sunshine and the elements is damaging to paint coatings, plastics, and rubber. Most of the time, it results in lightening of the colors, loss of glossiness, flaking, and deterioration. The degree of that damage and how it looks is what we are calling patina, but sometimes it is simply referred to as faded paint.

Newer clearcoat paint jobs show sun damage much differently than a single-stage enamel or lacquer paint job from the 1950s or 1960s. Due to the two stages of a clearcoat, the clear typically degrades first. It turns whitish and then flakes off and exposes the underlying color. The color then fades and allows moisture penetration to the metal, eventually causing rust to show.

With single-stage paint, the fading layers of paint do not take on the whiteish appearance like a clearcoat. Instead, the layers stay a relatively similar color to the topcoat. Looking at the center of a badly faded panel, you can typically see the undercoat colors that are revealed as the topcoat color oxidizes away. This is much more pleasing to look at (in my opinion) and certainly much easier to replicate.

For the most part, this book will focus on replicating patina of single-stage (direct gloss, direct color) paint. This is simply because it represents similar technology that was used in the 1920s through 1960s on mass-produced vehicles.

The roof panel on this 1960s car with a single-stage off-white color is much more damaged than the rest of the body. It is the largest panel on the car and is lopsided in its fading. Many different factors can cause this, but it’s quite common that panels wear in an uneven manner.

Until the late 1960s, vintage trucks were considered tractors with doors. Many of the mechanisms were quite crude until the trucks were finally recognized as passenger vehicles as well as work vehicles. Case in point, the tailgate latches were a stud, a swing latch with a hook, a loop on the tailgate, and a chain to keep everything from dropping into the mud. That’s not much different from the gate latch on a covered wagon! The chain on this truck has left a witness mark on the paint, and the latch has made an arched wear pattern under the main stud on the bed.

The leading edge of any vehicle takes the brunt of most of the damage, whether it’s sun damage, rock chips, or rubbing up against objects during the life of the vehicle. Here the headlight housing is showing deep chips, scratches, and exposed metal that are all beginning at the front and lessening at the back.

Impact Damage

There is a type of paint damage that is not caused by natural or chemical elements. For example, a tailgate chain on a vintage pickup can cause a distinctive wear mark or witness mark as it comes into contact with the paint repeatedly over time. Rock chips, damage to leading edges of panels and rocker panels, and even collision damage all have distinctive signatures that can be recreated.

The leading edge of vehicles such as fender peaks, hood lips, and bumpers sustain damage from rocks and other objects hitting the front of the panel during decades of use and abuse. The variety of the composition of the panels (some being pot-metal, some chrome) may mean that there is no visible rust showing through the paint. Keep this in mind when recreating natural-looking wear from impact damage, and know how your materials react to atmosphere. The goal is to find what happens organically and recreate it with a subtle effect that looks realistic.

Undercoats and Primer Colors

Undercoats are different colors on different types of vehicles. Vehicle manufacturers determine what coating lies under the visible topcoats based on several reasons. Certain vintage paint jobs have red oxide primers, some have black, and some have neutral grey. Red oxide was very common in Chevrolet vehicles of the 1950s and 1960s. Black primer seemed to be common in Dodge, Plymouth, and Chrysler vehicles. Many older vehicles have been poorly refinished or have had panels that have been repaired badly, and this can reveal different colored primers and different layers of paint.

Modern auto manufacturers use color-keyed sealers and primers to minimize the amount of topcoat that needs to be applied. These undercoats are almost exactly the same color as the topcoat, so only a minimal amount needs to be applied for color effect and match (saving cost on manufacturing). As an added bonus, the damage isn’t as noticeable from a distance in the event of road damage, rock chips, or even deep scratches.

Creating your own patina allows you to choose the undercoat color, giving you the option to color coordinate the effect and look that you want on your project. This is one of the benefits of “patinizing” your own vehicle: you can match interior colors, wheels, or a specific time period that you have an affinity to.

Test Panels

I always advocate practicing different types of effects on a panel before committing to the project, regardless of the nature of the refinish job. You can fine-tune the style and designs you want to create with much less stress on a test panel. Plus, mistakes are easier to recover from on a small fender or panel! You can end up with some cool souvenirs of your project as well. Make practice panels a part of your project for no other reason than to understand how to create different patina effects.

You need to protect yourself while handling sharp metal and any paint materials. Nitrile gloves will protect your skin from paint exposure and keep your skin’s oils and acids off of your project. A protective mask and a well-ventilated area are a must for spraying paint.

We found our metal at a home center for a few dollars for all three panels. You can use any substrate for these test panels, but we suggest using something similar to your project. In our case, that meant using thin sheet metal.

The type of paint is less important than the color strategy. That said, we’ll be using mostly solvent-based paints due the increased durability and similarity to what was used when the vehicle was manufactured. We’re using a black aerosol for the ground coat, a red oxide primer for the middle layer, and a pale yellow for the topcoat.

I know many custom painters who do spray-out panels for their customers long before they begin the final paint on the project. They use the panels to confirm they are on the same page as the customer as well as develop the technique they will use for the actual vehicle.

You can create practice panels and hone your patina-making skills along with us. We’re using metal sourced from a home center and some simple primers and paints for our test panels. You’ll need some inexpensive light gauge metal that’s similar to automotive sheet metal. We suggest 22-gauge metal because it is inexpensive and available at several different stores. You’ll also need some scuffing pads to prep the metal to ensure adhesion of the primer and paint, as well as some 400- and 600-grit wet or dry sandpaper.

We are creating three test panels, one for each of the types of damage (wear, sun, and impact). Each panel is prepared exactly the same so we can understand clearly how to create three distinctly different patinas. This will also give you a good idea of how different prep techniques with the same materials will simulate patina. This exercise is designed for you to become comfortable with sanding and exposing the underlying layers of paint and using the contrasting colors to mimic paint that has deteriorated from the top to the ground coats.

Prepping the Panels

Start by scuffing your panels with sandpaper or a scuffing pad. Use firm pressure and be thorough, but don’t try to do anything but scratch the outer surface. It is necessary for the surface to be abraded before paint application because this gives the paint something to hang on to. The scuffing can be a fast process, depending on what your substrate is. It took three to five minutes on our panels.

Follow by cleaning your metal panels with a solvent-based cleaner. These cleaners are available in aerosol form or as liquid in pourable containers. If you don’t have any body shop products handy, acetone or naphtha from a home center will work well.

Scuffing the Panels

1 To have proper adhesion, you must sand the metal panel to create a mechanical bond. A red scuffing pad and some elbow grease (pressure) will create enough tooth on the panel for the first layers of paint to stick well. The rest of our colors will bond into the first color coat.

2 After scuffing, precleaning is necessary. Solvent cleaners are available at body shop supply stores, but there are alternatives if you don’t have one around. Home centers and hardware stores have a variety of chemicals that will act as a solvent cleaner. By the way, make sure you’re wearing gloves for these preparation steps! Solvents can be absorbed into your bloodstream very quickly through your skin.

3 While the solvent is still wet, wipe it all the way off the panel in one direction. This makes sure you’re not just smearing around contamination. Allow the panel to dry for 5 to 10 minutes after wiping the solvent off and before painting.

Our ground coat is black, which mimics a lot of vehicle manufacturers’ metal sealers and base primers. Each layer of undercoat must have at least three wet coats in order to layer enough material to tolerate sanding some of it off and still showing color.

The red oxide primer is a nice contrast to the black. It easily shows when the black layer is completely covered. Apply at least four coats of red oxide, waiting 5 to 10 minutes or until the gloss has gone from the coat. The red oxide will mimic the undercoat that many vehicles had directly under the topcoat color.