Читать книгу Kameleon Man - Kim Barry Brunhuber - Страница 6

TWO

ОглавлениеI have always lusted after white girls, ever since I was old enough to wash my own sheets. Megan Fegan, taller and a little wider than her sister, Lara, but just as easy. Mo, who used to pay for everything. Agi Popescu, the Romanian cosmetician who just had to see me at least three times a week. The girl who worked in the little card store at Pinecrest Mall, whose name I’ve forgotten. Rhonda, whose breasts bounced over me like pink water balloons. Cyanne, who came after me one night with a fork.

This girl must have been a model at some point before she gained the weight. Dark hair, pale white skin. Asleep. A baseball cap, SEX DRIVE, pulled low over her eyes. A copy of the Tao Te Ching has slipped between her thighs. She reminds me of Melody’s ex-roommate, who I desperately wanted to sleep with. A little thicker, much of it in the right places. Once the bathing suits stopped fitting, the agency must have put her out to pasture answering phones and faxing pictures of the younger girls who haven’t yet discovered the pill. I can hear the tico-tico-tac of her headphones from the doorway.

I’m in a small round room with plenty of light streaming in from a large concave window. There’s a gnarled iron table in the centre, and a bench, upholstered in mock Kente cloth, runs along one wall. Facing me, behind the girl, is an enormous white placard, FEYENOORD in yellow lettering, and underneath it in black, PARIS, NEW YORK, MILAN, LOS ANGELES, BUENOS AIRES, TORONTO. The last city is tacked on, seemingly, as an afterthought. And all around the sign are pictures of Feyenoord’s finest, plastered peanut-butter-thick on the walls, hurled at crazy angles to stick where they may.

None of these girls are nude, though many are a nipple shy or a shadow away. The girls are blond mostly, some brown, a few red, an occasional yellow or gumball-green. I see one black girl wearing face paint and a buzz cut, body harder than algebra. Girls crouched in corners, chained to rainy streetlamps, covered in webbing, fur, smoke, scarves. Girls with angel wings, devil horns, boxing gloves, and attitudes. One girl, pale, almost translucent, wearing nothing except a sailor’s hat made of newspaper perched on her hearse-black hair. She’s palming her small breasts, her mouth open, exposing a sliver of tongue, pierced. White teeth. Her naked pubis lurks out of view, cloaked in shadow. She glows like an erotic angel.

“You know, I could make you a copy.”

The girl at the desk, awake now, arches an eyebrow, though most of the sarcasm was lost in the plucking. It’s possible she was the naked sailor.

“You’re late. Almost an hour,” she says.

“I thought...Mr. Manson told me twelve o’clock.”

“Chelsea? He’s lost. I make the bookings. When I say 11:00, that means 10:45. He went out to lunch. Everyone’s out to lunch except me.” She sizes me up. “This won’t take long. Let’s go in the back.”

I hoist my satchel and follow her dumbly, wheeling my suitcase down the dimly lit corridor. Along the right wall are tables littered with black-and-white prints, loupes, and guillotines. On the left, an office and a plushly decorated bathroom with the biggest mirror I’ve ever seen. In front of us, a glass door. On it, a tiny piece of paper taped to it: DO NOT ENTER. BOOKINGS IN PROGRESS. She opens the door.

“I’m Rianne. Have a seat.”

She pulls a rolling chair toward me, sits down herself at a circular desk with four evenly spaced computers. The walls are lined with comp cards—cardboard ones. The good kind. Rows of portfolios on the shelves. Each book with the model’s name labelled plastically to the spine.

“Your book?”

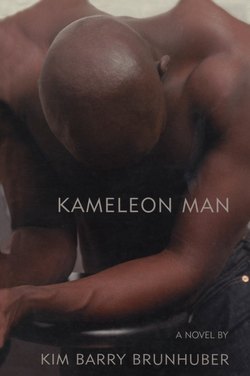

I fish my portfolio out of my satchel. It’s a sombre black volume, with DAVIS-BARRON MODELS INTERNATIONAL emblazoned in letters that aren’t quite gold. Why INTERNATIONAL I’ve never figured out. All the DBMI models I know work in Nepean, though rumour has it they sent a girl to Paris once. I open my book to the first page, hand it over open and facing her the way we’re taught. I don’t know who the hell she is. I give her a smile, but she’s already thumbing through the pictures. In a Harry Rosen suit, serious, the young black executive, the caption MAN AT WORK. In a Georgetown sweatshirt and jeans, walking down the street, oozing boy-next-door, hand waving to an imaginary friend. On a cast-iron stool in black Paul Carville, legs wide, cigarette dangling, James Dean with a tan. Snarling in outrageous plaid, stuffed into a white corner, bare-chested except for a bead necklace and a peace sign. The last shot. Army fatigues, waist-deep in snow, opening a can of army rations with an expression of sheer glee. It made the cover of Guns and Bullets. A joke shot that my agency insists I take out, the picture I always sneak back in. So the client always leaves with a grin.

Rianne snaps my book shut. Grinless. “I’ll have to be honest. First of all, it’s obvious you don’t have much experience. More important, the market for black guys, it’s not really big here yet. Not like New York or Miami. Have you tried there?”

I shake my head, trying to figure out what’s going on.

“Anyway, we already have a couple of guys with the same look.” She points to a group of photos on the wall of men who look nothing like me. “They get pretty much all the work there is around here. Have you heard of Crispen Jonson? No? He’s going to be really big. Huge. The next Simien.”

I’ve heard whispers of Simien. The first black model on the cover of New York Life. The next Tyree.

“You know, you might want to try Maceo Power. It’s a smaller agency, more runway, less print, more overseas stuff. But they’re not bad. I’ll take a comp card.” She slips the floppy paper card with several shrunken pictures of me along with my measurements out of the portfolio sleeve. “I’ll pass it on to Chelsea. Thanks for coming all the way here...” She stands and takes my hand. I feel a pang of lust so bad it actually hurts. “There’s a party tonight at the Garage. Models, photographers, stylists, mostly. If you’re still in town, you should come out.”

Still shaking her hand, I try again. “I’m not sure...I was supposed to see Mr. Manson. He told me to come here. To work. I’m Stacey Schmidt?” Hoping my name will ring a bell.

“You’re not here for the eleven o’clock open call?”

“No. I met Mr. Manson at the Feyenoord Faces contest.”

“The contest? You mean...are you the winner?”

“No.” Trying to decide if her emphasis was on winner or you. “I was at the contest in Nepean. Mr. Manson saw me and told me he could find me work here in Toronto.”

“Modelling work?”

I don’t dignify that with an answer.

Rianne sits back down, swivels to a computer, and clatters at the keyboard. “There’s no note. He didn’t mention anything.” She gazes at me again. “Well, like I said, Chelsea’s lost.”

“Can I wait for him at least? If he’s just having lunch...”

She laughs. “Chelsea used to have a sign up that said OUT TO LUNCH. IF NOT BACK BY DINNER, OUT TO DINNER. Trust me. He won’t be back for a while.” Wheeling around to her computer again, she adds, “I might as well get your measurements then. Age?”

“Twenty-one.”

“Height?”

“Six-one.”

“Weight?”

“One seventy-five.”

“Jacket?”

“Forty-two tall.”

“Waist?”

“Thirty-two.”

“Inseam?”

“Thirty-four.”

“Crotch?”

“What?”

“Just kidding.” She grins mischievously. “Sports?”

“Tennis, skiing, rugby, volleyball, football, horseback riding...”

Rianne glances up at me, then continues typing.

“Do I have to name them all? Everything except basketball and golf.”

“Fine. Any special talents? Singing? Acting?”

I think for a minute. “Well, I play the cello. And I’m a pretty good photographer.”

“We’ll just put no. Keep your portfolio, and when you meet Chelsea, we can talk about putting together a new book, new comp cards, and everything else.”

That smacks of money.

“If you’re going to be working here, I’ll give you this.” She hands me a Feyenoord appointment book: small, white, plain except for FEYENOORD in bold black letters. I tuck it into my satchel.

“The best thing...” Rianne looks at my bags. “Where are you staying, by the way?”

“Mr. Manson said he would take care of that.”

“Figures. The model apartments are full right now. What you could do, though...I know a couple of guys who might have room. I’m sure Crispen and Augustus wouldn’t mind.”

Rianne picks up the phone. I search the wall for my would-be hosts. Crispen and Augustus aren’t hard to find. Two chocolate chips in a bowl of ice cream.

“Busy.” She hangs up. “They don’t live far.” She draws a rough map on the back of a cheque marked VOID. It’s made out to Jeanette Grenier for $2,554.35. “While you’re there, tell them Eva from Greece will be here tomorrow morning at 9:30. That means they should get here at 9:15. Make sure and tell them that. Nine-fifteen. And tell Breffni to pack a smile. He’ll know what I mean. And here.” She scribbles some numbers on the back of the cheque. “My number. In case you need anything.”

From beneath her hat it’s hard to tell if anything means a hair dryer or a hand job.

Suddenly buffeted by the nuclear winds of the subway, I sway perilously close to the pit below. Grey steel, brown pools, yellow wrappers, and I’ve heard there are rats. The subway skrees to a stop. Crowds lunge. I hoist my suitcase onto my head like an African porter, follow the surge and grab an awkward slice of the pole. Through a corner of the window I spot a mother, a child, and its balloon rising at the top of the escalator. The mother sees the train coming and starts sprinting, dragging the child, who goes limp with the instincts of a kitten. But three chimes, the doors snap, and “Osgoode next!” We lurch into the night, packed like cigarettes.

All around me, many hues and shades of Africans. The popcorn staccato of Chinese. A nun with a small beard circulates through the car selling cookies. A short bald man in a spotless baseball uniform cleans out his ear and smells his finger in disbelief.

With one hand I search for my new Feyenoord book, pull it out, imagine it overflowing with appointments, go-sees, shoots, contacts, names, and numbers. Sharon Davis and Liz Barron, the important halves of Davis-Barron Models International, said my smile would be worth a fortune in Toronto. Said it smiling, thinking of their five percent of everything. Peering at my empty appointment book, I’m skeptical. I don’t believe much at face value. I don’t accept things until I see them for myself. A glass of water drunk upside down curing hiccoughs. Energizer batteries actually lasting longer. Catalogue shoots really running more than an hour as promised. Modelling is a business built on broken pledges. They guarantee you the moon and hand you a match.

All Sharon and Liz told me before leaving was to be careful, and to be myself. Advice as useful as aromatherapy. I’m not the country cousin. I did, after all, live in Montreal for almost a year. And why would I want to be myself, anyway, when the point of leaving is to leave myself, to slough off my old life like a snake skin?

A sudden stop and I swing halfway around the pole like a stripper.

Outside, confused by the boo-blahs of angry taxis, the greasy streets sweating rivulets of people, the smell of onions and ketchup, I stand in the backwash of a bus and have to move. Left or right, I don’t know. I feel as if an invisible man is throwing sand in my eyes. Rianne said the apartment was only about two hundred yards from the bookstore. But two hundred yards is as good as a mile when you don’t know where you’re going.

There seems to be no way to cross Bloor Street. Lexuses and BMWS, distracted by falling stock prices and cell phones, ignore streetlights. I follow a small knot of pedestrians. We cross halfway against the light, straddling the painted yellow lines, until the winking of brake lights promises safety. We weave between the stopped cars like hyenas among the wildebeest, nervous, skittish, ready to evade a sudden charge until we reach the sanctuary of the sidewalk.

Everywhere bums gumming for change. Some stretched out in sunny corners. Others curled up in alleyways like withered leaves.

A woman on the corner wears a DIET BY PHONE placard over her suit like armour, a playing-card soldier from Wonderland. I’ve never seen so many young Asians. Chinese men with walkie-talkies and cell phones. Korean women in Donna Karen mini-suits, hair tinted gold or red.

I’m almost run over by a procession of squealing kids. They’re on a field trip. Arms linked with string. Behind them their teacher leads them like huskies past me through the streets.

An old turtle stands on a welcome mat strumming a banjo, croaking “H-e-e-y, J-u-u-u-d-e.” The joints of the arthritic microphone are bent at impossible angles. “Spare some change, bro?”

I shake no and smile, wondering how he can afford an amp and a speaker when he can’t, according to the crumpled placard, afford a meal.

“Nigger,” he mutters, and stretches his song toward the next passerby.

I’m genuinely shocked. Usually bums are the only strangers you ever meet who wish you a nice day. They know most people will pass by twice. I have no witty rejoinder. I have only my Feyenoord appointment book and shiny sneakers to testify on my behalf. I can’t escape. I have to wait in front of him to cross the street.

The door opens before I even have a chance to knock. He’s even bigger in real life. His pop-out chest is more impressive in 3-D than his picture on the agency wall, half-naked and oiled, posing in an old gilded mirror. His biceps bulge under a small blue Kool and the Gang T-shirt. His legs are as thick as thieves. But somehow his head seems too big for his body. And his nose looks too big for both.

“You can hear the elevator opening from inside the apartment,” he says, opening the door wide. “The buzzer downstairs doesn’t work. The elevator door’s our early-warning system.”

“In case any of his women come knocking, he has time to hide,” a voice says from inside. Two male laughs.

“G’way,” he says, smiling. “Come in. Rianne called and said you were coming.” He grabs my suitcase with one hand, and it flies upward of its own volition. “I’m Augustus.” He offers me his other hand. His grip is surprisingly soft. His voice rumbles so deep I can feel it in my ass. “But most of my friends call me Biggs. It’s Stacey, right?”

“Yeah. Stacey Schmidt.”

“Cool. Welcome to our house.” He pronounces it hoose.

The apartment is small, carpeted with clothes of all kinds. The walls are bare, and there’s no furniture except a wide white couch and a tiny TV as large as a parking attendant’s security monitor.

“There’s not much left,” Augustus says, gazing around. “Most of the crap was Simien’s, and he took it yesterday. Tour?”

The other two are sprawled behind the couch, opposite each other. Feet almost touching. A small bowl of lumpy dip between them. They’re sharing a cigarette. Everything smells of sweetgrass.

Augustus points. “The white guy’s Breffni. Negro’s Crispen.” Breffni, brown-haired, stubbled, impossibly blue eyes almost glowing. He’s naked from the waist up. A jeans commercial. Crispen, shorter, darker than I am, bald, beautiful lips, almond-shaped eyes, and a gold earring. He’s dressed as if he should be either hitting a home run or robbing a liquor store, and has a toothpick stabbing out of the side of his mouth.

“Stacey.” I put out my hand, but it seems as if neither will get up for a while.

“The fresh meat,” Crispen says, taking a drag, passing the joint to Breffni. “Want some? In there.”

I open the fridge, hoping to find more dip, but all I see is a stick of butter, some milk, and a plastic bag of what appears to be oregano. I begin to doubt it’s oregano. Without warning Breffni applies his spoon to Crispen’s face, and the two roll toward the wall in a ball.

“They’ll be all right in half an hour or so. Simien’s supposed to be out of his room by tomorrow, so until then you can throw your stuff here.” Augustus motions to a stained corner. “Shower’s in here.”

“Rules,” Crispen gurgles from the floor.

“Right,” Augustus says, barring the bathroom door with one arm. “One. When you leave the apartment, don’t lock the door. Simien has the only key. Two. When you finish the milk, don’t just put a new bag in, cut the damn top open, too. Three—” he indicates the toilet “—we’re guys. We miss. That’s fine. But either clean it up, or do it sitting down like a bitch. Got it, Pappa?”

“Sure.” There are brown mushrooms growing in the carpet behind the bowl.

“Lucky Charms!” Breffni shouts, mouth full of dip.

“Oh, yeah. Lucky Charms are Breff’s. Touch them and he’ll touch you. Of course, he only likes them ’cause they got a picture of a little Irish dude on the cover. Keeps him in touch with his heritage.”

“’Tis troo,” Crispen quips in a cartoon Irish accent. He and Breffni both clutch their sides, dissolve into a pool of laughter.

Augustus shrugs. “Like I said, they’ll be okay in a half hour or so. Shower?”

The shower has almost no pressure. I feel as if I’m being watered. I pump some soap from an industrial-size tube. If the black dot on the tub is moving, it’s a snail. It’s hard to tell what’s in motion and what’s not. I’m so weak with hunger, my brain is a loaf of bread. I don’t even feel wet when I step out of the shower.

“You want some?”

“Sure.”

Crispen hands me the joint. I rarely smoke up, but I figure if I can’t get food, at least I can get high. I fumble, burn my fingers, then pass the roach to Breffni, who inhales expertly. Filling his cheeks like a horn player.

“So what happened to that girl you were with, Biggs?” Crispen asks Augustus. “She was fine.”

“Gave her the boot. Possum lover. She played dead.” Turning to me, he asks, “You have a woman?”

“No.” Thinking about Melody. “I wouldn’t mind working on that girl at Feyenoord, though.”

“Specifically...” Breffni says, scooping another finger of lumpy batter from his bowl.

“The booker. What’s her name?”

Scowls of collective disgust.

Breffni groans. “Shawna?”

“No. What’s her name...Rianne? She gave me her number.”

Degrees of laughter all around.

“She’s as easy as pie,” Breffni snorts.

“Rianne’s not our booker, by the way,” Augustus says. “Rianne books the girls’ shoots. Shawna books ours. But by all means, go for it, Pappa. You’re just the kind of guy who’d make her runny. Damn, I’m in the mood! Let’s go out. Any of you have to be up tomorrow?”

“That reminds me,” I say. “Rianne told me to tell you guys we have some kind of go-see tomorrow morning.” I scan the room for my Feyenoord book, but my eyes can’t seem to keep up with my head. “Someone from Greece at 9:30.”

“Probably Eva again,” Crispen says. “I ain’t goin’. You?”

Augustus shakes his head.

I frown. “Are you guys mad?” I can’t believe what I’m hearing. Elite college football players skipping the NFL draft to join the pro bowling circuit. “Europe’s the big ticket.”

“Europe’s a sham, man,” Breffni says. “Guys have to pay their own way. By the time you cover rent, food, and smokes, there’s nothing left to take home. I have all the pictures I need for my book. This is the place to be, my fine feathered friend. Commercials. Movies. Hollywood without the beaches, tits, and cars. You can’t go to the can without pissing on someone who’s casting for something. Europe’s just pretty pictures. And kick-ass herb.”

“Have you ever done any movies?” I ask.

“When I was a kid in Buffalo, I worked all the time. Cutesy stuff, a couple of small roles in movies. Lots of commercials. Remember the Loony-Roos kid?”

“The kid who wouldn’t eat anything that wasn’t red? I thought that kid was blond.”

“That was me. I dye my hair brown now.”

“Damn.” Impressed. “Have you been in anything lately?”

“I was Dude Number 4 in a Schlitz spot, and the guy who gets pushed out of the way in Revenge of the Hammer. I haven’t gotten any speaking roles since high school. My career peaked at age thirteen.” He smiles. “It would be funny if it weren’t sad. That’s why I came to TO. They don’t call this Hollywood North for nothing. Forget about overseas.”

“They wouldn’t take us, anyway,” Augustus says.

“Why not?” I ask.

He pulls up his sleeve and rubs his arm.

“What’s that?”

“Skin tone.”

“You’re black, right?” Breffni asks.

“What do you think?” I feel the answer’s obvious, even though I still can’t figure out whether to capitalize black or put it in quotations.

“You’re light-skinned,” Augustus says. “Who knows? Maybe they’ll like you.”

“Like I said,” Crispen says, smiling. “Fresh meat. How old are you?”

“Twenty-one. You?”

“Twenty-four.”

“You?” I ask Breffni.

“Twenty-four.”

“How old are you?” I ask Augustus.

“Older than you.”

“Seriously. How old?”

“Seriously old.”

I turn to the others. “How old is he?”

Crispen and Breffni exchange glances. “We don’t know,” they both say.

“How do you not know?”

“He never tells us,” Crispen says.

“Put it this way,” Augustus adds. “I was doing shoots in New York while you were watching Hammy Hamster.”

“If you modelled in New York, what are you doing here?”

“Well,” he says slowly, “too many models in New York. I read somewhere that there are more models in the Big Apple than people in Jackson, Wyoming. And there’s less competition here. No offence.”

“No offence?” Breffni says. “Tell him what kind of modelling you were doing in New York.”

“Never mind that, Pappa. Money’s money.”

Breffni grins gleefully. “Biggs was a hand model.”

I did some hand modelling once in an internal video for the Department of National Defence. They had to shoot eighteen takes because I had trouble opening the envelope. The client blamed me. I blame extra-strength tamperproof glue. Hand modelling, like pretty much everything in life, is harder than it seems. I crane my head to study Augustus’s hands, but they’re now in the pockets of his sweater.

“Don’t blame me if people want to pay me serious cash to wear shiny things on my hands. And I’m doing more real modelling now, anyway. Hand modelling’s just for the money. So are we out or what?” Augustus asks, standing.

I peer at my watch. Somehow it’s already past 11:00. “I think I’ll have to pass. I’d better get some sleep if we have to be there for 9:15 tomorrow.”

“Forget it,” Crispen says. “You’ll have plenty of time to sleep when you’re dead.”

“Yeah, but if I don’t sleep, I’ll be dead that much sooner.”

They’re all looking at me. Didn’t Rianne say something about the Garage?

“Well, if I go, I have to eat first. I’m starving.”

“Me, too,” Augustus agrees. “Starvin’ like Marvin. Let’s get some pizza.”

“Pepperoni, Italian sausage,” Crispen insists.

“Make it half and half,” Breffni says. “Tomato, onion, and zucchini for me.”

“Your pizza’s getting nastier every time we order, Breff,” Crispen says, wrinkling his nose. “Next week it’ll be corn, squash, and rice. I don’t know how you live on plants and still have any meat on your bones.” Breffni is shorter and thinner than the others, but cut like a diamond.

“Protein’s in the beans!” Breffni sluices the last of the goop from the bowl into his mouth.

Augustus, holding one end of the receiver, asks, “Do we want free pesto?”

“Throw a shirt on, Breff,” Crispen says.

“I can’t dress until I hear some tunes,” Breffni says. “Let’s hear some tunes.” He turns to me. I notice one of his nipples is pierced. “C.J.’s a kick-ass DJ. He used to DJ in the States.”

“Back in North Carolina,” Crispen says. “I got everything from Method Man to Mozart, man.”

The house bops to some old Cameo while we dress. I root through my suitcase for my dancing gear, chip a nail on my camera at the bottom. An old Canon, not the best, but good enough to win last year’s Nepean Public Library Photo Competition, Amateurs Under Forty. I pull it out. “Will this be safe in this apartment?”

“Safer than if you left it out in the hall, but that’s about it,” Crispen says.

I stuff it back into the bottom of my suitcase. The little gold travel lock’s just enough to delay a would-be thief by the length of a chuckle.

Breffni’s still primping long after the three of us are done. We finish off another joint and the pizza while we wait. Both taste like tapestry. For some reason it doesn’t seem the least bit strange to be sharing stories and spliffs in a strange city with three strange guys. I suppose I haven’t lived long enough for anything to be truly surprising. I wonder if one can go into shock from the experience of moving. If the phrase comfortably numb wasn’t sung about decades earlier, now would be a good time to dream it up.

“Hurry up, Breff!” Crispen shouts. “When he’s doing a show, he can change from a sweater to a tux in less than twenty seconds. But when we want to jet, it takes him an hour. Go figure.”

Breffni yells from the bathroom, “Big difference between modelling and real life, right?”

“Just hurry the hell up.”

The men’s washroom at the Garage is surprisingly similar to the rest of the club. Cold concrete underfoot, hot neon overhead, and tools as far as the eye can see. My stepfather, were he alive, would be prying pliers and spanners off the wall. Even in here there’s no refuge from the black light. Constellations of lint glow on my black turtleneck. On the sleeves, long electric filaments from cats long dead. I’m afraid it may appear to be dandruff. Right now I’d trade my shoes for a lint brush.

The taps are operated by unmarked wrenches. I’d like to splash some cold water on my face, but I can’t figure out the taps. I puke in the sink instead. Pieces of salami sluice down the drain. I’m tempted to blame the pesto, but I know better. My eyes are infernally red. Then I squawk with dry heaves. I feel as if my soul is passing out of my mouth. There’s a young, smartly dressed man standing politely next to me. I try to ask him what pesto is, but it comes out more like “Why I’m pissed.” He offers me a towel. I’m not sure if it’s pity or his job that motivates him. I compromise by accepting it and giving him a quarter. His expression says that was clearly the wrong move, though whether it’s because I gave him money or because I gave him so little, I can’t tell.

I check myself into a stall for a half-time pep talk. My game plan is clearly not working. Focus is the key. A comeback, not entirely impossible. Crispen and Breffni are hunting a school of young models. On the dance floor they circle closer and closer like reef sharks. Breffni’s after a tall brunette with a fake tan and mechanical breasts. She seems familiar, but they always do. I’ve had plenty of girls like her, all forgotten. Crispen, tonight’s designated pilot fish, will be happy with the leftovers.

I’m still looking for Rianne. I think I saw her by the pool tables. It’s possible I bought her a passing rose and told her I’d like to put my finger in her pie. She may have slapped me.

Augustus leads a line dance. “Bring it back!” he shouts, twirling like a Four Top as eager secretaries and fresh divorcées shyly try to follow his Cabbage Patch, his Electric Slide, unsure of themselves, but having a ball, just happy to be retroactively learning the latest steps, thrilled to be tutored by a certified Master Negro. Augustus ignores the glares from the other dancers around them, from those too young to remember when Michael Jackson was still black. He’s in a zone. He doesn’t care as long as he’s spinning and winning on the baseline. Scoring, for one. “The roof, the roof, the roof is on fire...”

And, giggling, one by one, his understudies join in, only mouthing the words at first, then, Long Islands and Blue Lagoons later, screaming out, “Burn, motherfucker, buuuuuurn!”

We’re huddled on the couch for warmth like baby rats. The stereo’s still on—“Single Life” stuck on repeat. “Single guys, clap your hands!” over and over. We’re too tired to turn it off.

I prod Crispen, who’s on my thigh, but he seems to have passed out. Breffni’s still talking about the brunette and the fight her boyfriend picked with him outside the bar, quickly unpicked when Augustus walked their way. No one’s listening.

“So where do I sleep?” I ask.

Augustus points to a thin mattress leaning against the wall. I notice he’s wearing gardening gloves.

“Why the mitts?”

“Keeps ’em steamin’ fresh,” Crispen says, stirring at last. His chuckle turns to heaves. He grabs Breffni’s bowl. Its new contents are indistinguishable from the old.

“Don’t laugh, Pappa,” Augustus says. He peels off a grey glove, exposes a ring. It looks as if it cost more than I do.

“Half an hour of turning faucets and flushing toilets. No stylists, no makeup. Fast and dirty. Easy money.”

“You wear makeup?”

“On my hands?”

“On your face.”

“Powder. Don’t you?”

“No.” I’ve never touched a spore of makeup in my life. I didn’t even know powder came in brown. All of a sudden I’m nervous about tomorrow’s go-see. I’m playing in the majors now. Can’t afford a strikeout at my first at-bat. “What’ll we have to do for that woman tomorrow?”

“Eva?” Augustus says. “The usual. She’ll peek at your portfolio, make you do a couple of laps, then tell you there’s not a big market for your type in Greece.”

“Don’t worry,” Crispen slurs. “You’ll be fine. You know how to walk, right?”

Suddenly I’m not so sure. In Nepean, cock of the walk. In Toronto, a shambling mound, lurching up and down the ramp to the tune of snickering models and simmering clients.

“Give me a professional demo,” I say to Crispen. “Just for fun.” But he’s lapsed back into unconsciousness. “Augustus?”

“I don’t do shows.”

“Why not?”

“I’d break the clothes. Breff’s the man.”

“I’ve lost the use of my legs.”

“Come on, Pappa,” Augustus wheedles. “Show ’em how it’s done.”

Breffni slides off the couch. “You know the drill. Head straight. Stomach in. Pretend you have a tail and tuck it between your legs. And just walk.”

He doesn’t walk. He glides. As if he were a passenger on a moving sidewalk. Up and down the living room, looking side to side, while Cameo’s single ladies clap their hands. Until he walks into the wall and collapses.

“Well, that’s my cue for beddy-bye,” Augustus says.

“Me, too,” Crispen says, awake again.

Breffni hasn’t moved. It doesn’t look as if he will until morning.

I turn off the stereo, pull the mattress off the wall, lie down. It’s like sleeping on a playing card. “Do you have a sleeping bag or some kind of foam to put under this thing?” I ask anyone.

“What are you? The princess and the pea?” Crispen growls, still on the couch. “Stop complaining and turn the lights off.”

It’s dark and cold and they’re snoring in stereo. Breff is herking and jerking on the floor next to me, no doubt chasing women in his sleep. I’m still high as a weather balloon. My bed’s spinning. Doubts and misgivings are pulled from the recesses of my mind by centrifugal force. From this mattress the life of a Toronto model appears as glamorous as laundry. I’d like to press Save at this point in my life, just in case things don’t work out, in case this was all a big mistake. I’m messing with a fragile balance, I have to move carefully. Life itself is too good to be true, and if I were to think about that too hard, I’m afraid God would catch on and pull the plug. Good luck isn’t always as simple as it seems. Payback’s a mother. The mean happiness quotient takes care of that. That’s the average level of happiness I’m allowed to maintain in my life. I’m a firm believer in the principle of Even Steven. Like a sitcom hero, after a few adventures, I always return to the status quo. Tomorrow, with Feyenoord, the chance to become a one-name model. Iman. Elle. Instantly recognizable. Stacey. Any more good luck will skew the quotient. Something’s got to give. Things, if left to themselves, always even out in the long run.