Читать книгу The Virgin's Promise - Kim Hudson - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Archetypal Theory

One of my favorite moments in the movie Ever After occurs when Danielle, a Cinderella character, says to her wicked stepmother, “Do it yourself.” It’s one of those great “aha” moments. Despite the fact that I know this line is coming and I’ve seen it at least a dozen times, I look for ward to this scene every time. It has all the features of being in touch with an archetype: the audience is willing to see it repeatedly; they instinctively recognize the situation and feel elated with the action taken; and they easily remember that moment after it’s over.

Psychiatrist Carl Jung explored the concept of archetypes and proposed that there is a consistent set of archetypes in every human. He suggested our collective unconscious causes us to be drawn to these images and behaviors because they give us a sense of direction, meaning in life, and a feeling of euphoria (Stein, 100). This is the reason we look to archetypal structure when we write.

Basics of Jungian Theory

Carl Jung set out to map the terra incognita of the human soul. Over his lifetime he developed his theory of archetypes. On one level, the theory is complicated, attempting to explain the ego and the soul, and many abstract thoughts in between. On another level, the theory refers to aspects of ourselves as humans and is therefore very familiar.

Jung proposed that we have three psychic levels: the conscious, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious. The conscious houses our memory and understanding of the events of our daily life. The personal unconscious contains those life experiences and memories that are repressed or not understood. They are acquired through life experience and therefore are not common to everyone (Jung, 1976, 38). The third psychic level, the collective unconscious, is inherited and common to all people, now and through out history. This is where the archetypes reside.

The theories of psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler deal mainly with the second psychic level, the personal unconscious. These theories are working with complexes, which develop as a result of a personal trauma. A complex is a pattern of behavior a belief designed to protect oneself from repeating actions that previously caused pain. They work on a level of which we are not consciously aware. For example, Freud is said to have had a repressed history of sexual entanglement with his sister-in-law, which resulted in his seeing most issues through a sexual lens (Jung, 1976, xvi). Adler experienced strong sibling rivalry which caused him to focus on interpersonal power dynamics and resulted in his theory of the urge for self-assertion, the drive to get the most you can for yourself (Jung, 1976, xv,61).

Problems often arise when the complex, designed when resources were limited, keeps operating in an adult. Sometimes the complex grows and adapts itself to new situations. The Joker in Dark Knight is a strong example of a character driven by an unconscious complex created by an earlier life experience. The Joker is constantly asserting that all humans are self-focused and self-preserving to the detriment of others. He unconsciously developed this belief, possibly to explain the abuse he suffered at the hands of his father. Rather than believe his father did not love him, he sets out to prove all humans are predisposed to sadistic behavior.

The complexes of Freud and Adler differ from Jung’s theory of archetypes in two major ways. First, complexes are based on events that originated in the conscious and were pushed to the personal unconscious. They are dependent on the personal history of an individual for their development. In contrast, we are born with archetypes and their patterns of behavior.

Second, Jung believed the human psyche has a mechanism to look backward after a crisis, and a mechanism to look forward when facing a challenge. Complexes are meant to stop physical and psychological movement into the unknown. Archetypes are “patterns of instinctual behavior” (Jung, 1976, 61) humans can invoke to gain insights into how to move ahead. Through dreams, myths, and fairy tales, with their inherent archetypal patterns, we are pointed towards “a higher potential health, not simply backward to past crises” (Jung, 1976, xxii). In many ways these two mechanisms keep us balanced between safety and risk. Complexes create protective barriers and archetypes act as guides towards greater human potentials.

Jung described archetypes as both a source of psychic symbols and a predisposition to react, behave and inter act in a certain way (in movie terms they are analogous to both a character and a character arc). These two aspects make archetypes very powerful. He felt they carry the energy that ultimately creates civilization and culture (Stein, 4, 85).

Archetypes have a light and a shadow side, both of which are important for going through transformations. Light side archetypes such as the Virgin and Hero represent the higher human potential. Shadow characters, for example the Whore and the Coward, represent the counterpart, which either becomes the starting point for growth, the inspiration for growth or a point of reference.

The shadow side archetype may represent the immature, stunted aspect of each stage of life (Moore, xvii) and has several functions in story telling. It may be the position from which the protagonist will grow. The Virgin has a moment as the Whore who sells her dream to appease others. The Hero starts out as the Coward, refusing to go on the adventure. The shadow may also represent the consequence of not going through the archetypal journey, as in a cautionary tale. More often, shadow side characters, or archetypes, make great antagonists whose function is to propel the protagonist forward on his/her journey.

The shadow side archetype is inherently the opposite of its light side archetype. Viewing them as a pair of opposites highlights the important aspects of each archetype. you see more clearly what it is by looking at what it is not. The shadow defines the light. For example, the Virgin moves towards joy to realize her dream. The Whore feels victimized and loses her autonomy to the control of others and their fantasies. The Virgin is a valued commodity and the Whore is scorned by society. The fundamental differences between these two characters add clarity to each of them. The Hero looks braver when the Coward beside him has five good reasons to run away.

Jung felt that the function of story was to guide us through the universal transformations of life, collectively known as individuation, using archetypes with their symbolic characters and patterns of behavior. The first risk of life is to stand on your own, and take up your individual power. This is the challenge of developing a relationship with yourself and the work of the Virgin and the Hero. The next challenge is to learn to use your power well and join in a partnership with another person, as the Lover/King and Mother/Goddess must do. The final challenge is to join the cosmos, to focus on giving back and letting go and seeing the beauty of one’s insignificance. This task is guided by the Crone and the Mentor. you can refuse to take up these tasks but nobody gets off the planet without facing these challenges. Audiences find meaning in and are entertained by this quest for individuation.

Fairy Tales and Myths

Jung theorized the existence of archetypes after observing that myths and fairy tales of world literature have repeated beats or motifs (Jung, 1965, 392). In Orality and Literacy, philosopher Walter Ong describes how in oral cultures, where the story is memorized, non-essential information is dropped with each retelling, and the core patterns emerge strongly (Ong, 59, 60). The same effect is created in movies, which are delivered in roughly an hour and a half. In order to meet this restriction, the clutter is removed, and the archetypal beats become vivid.

Generally, Virgin stories occur in the realm of fairy tales and Hero stories occur in the realm of mythology. There are exceptions, such as the Virgin themed side-story of Cupid and Psyche found in the Roman writer Lucius Apuleius’s myth, the Golden Ass. However, it is interesting to consider why the Princess / Virgin plays a leading role in many fairy tales while myths often center on the Hero. Possibly this difference is rooted in the internal versus external nature of the Virgin and the Hero journeys, respectively.

In Bruno Bettelheim’s book The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, he notes that fairy tales are centered on self-worth and self hood (1989, 6, 7, 24). This is a natural device for the Virgin who seeks to bring her authentic self to life by following her dreams. The Virgin must answer the question: Who do I know myself to be and what do I want to do in the world, separate from what everyone else wants of me?

Fairy tales are presented as stories of casual, everyday life events, which take place in the domestic realm (Bettelheim, 37). The Virgin confronts her central question in her childhood environment with its teachings and expectations because these are the forces that compete in her mind as she seeks to define herself as an individual. Her journey is towards psychological independence.

Myths are centered on themes of place in the world of obligation. This is the realm of the Hero as he seeks to answer the question, “Could I survive in the greater world or am I to forever cling to the nurturing world of my mother for fear of death?” His journey is towards physical independence.

Myth presents a world or circumstance that is absolutely unique (Bettelheim, 37). This is compatible with the Hero’s journey to a foreign land. Surrounded by the unfamiliar, the Hero faces the challenge of learning the physical boundaries within which he can survive.

When the Hero explores his boundaries he is pushing the edges of mortality. He is tampering with the boundaries between mortals and gods, because immortality is a right of the gods. Heroes, therefore, find themselves battling with villains who seem immortal in stories of grand proportions. The Hero is often unknowingly of half-immortal parentage, a metaphor for questing for the boundaries of his mortality. These features associate Hero stories with myths.

Another feature distinguishing fairy tales and myths is that the characters in fairy tales are generic and common (Bettelheim, 1989, 40). They are father, mother, a princess, king or prince. Only the main figure has a name and often not in the title. It is Beauty and the Beast, any beauty and any beast. The Goose Girl and The Ugly Duckling both use general descriptions rather than names. Characters in myths, on the other hand, are very specific (Bettelheim, 40). It is the myth of These us and the Minotaur, rather than the general story of a hero and a beast. This again speaks to the general and casual atmosphere of fairy tales and the portrayal of a unique circumstance in myths.

Both fairy tales and myths acknowledge the difficulties of life and offer solutions. The fairy tale has a happy and optimistic style with the assurance of a resolution and a happily-ever-after ending. Our enjoyment of a fairy tale induces us to respond to the message of the story. As with the Virgin, it is a pull towards joy that drives her transformation. The Hero is driven by the need to conquer fear. The my this more often a tragic tale of hardship with an overall pessimism (Bettelheim, 37, 43).

The happily-ever-after ending of fairy tales (Zipes, 9) also speaks to the spiritual nature of the Virgin story. Magic and optimism are metaphors for the belief that something greater than ourselves is at work for us. The pessimism of myths connects with the Hero’s need to face hardship and the fact of death and deal with the fear in a physical way.

James Hollis, a Jungian theorist, describes the study of myth as an avenue to understanding the meaning in life. The stuff of myths is “that which connects us most deeply with our own nature and our place in the cosmos” (Hollis, 2004, 8). With the introduction of the Virgin archetypal structure, I would argue that the same is true for the study of fairy tales.

Archetypal Themes

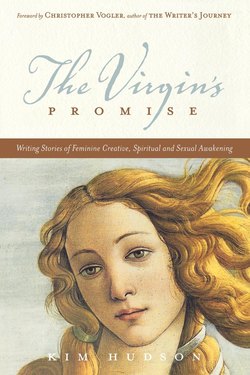

In addition to being symbolic characters, archetypes model pathways for the universal transformations in life. The work of Joseph Campbell, later customized for the movie industry by Christopher Vogler in his book The Writer’s Journey (1998), captures the twelve beats of the Hero’s Journey. In a similar way, this book offers anew theory that lays out thirteen beats common to the Virgin Story.

Comprehensive analyses of the beats for the other core archetypes are not yet available but I believe that if there are two archetypal journeys, there are more. The following description of the essential nature of the Virgin, Whore, Hero, Coward, Lover/king, Tyrant, Mother/Goddess, Femme Fatale, Mentor, Miser, Crone and Hag may provide the groundwork for that future analysis. A basic understanding of these archetypes is also useful for creating strong characters.

These archetypes represent the three stages or acts of life: beginning, middle and end; child, adult, and elder. A movie generally follows a protagonist through one of the stages showing the arc of that transformation. It may also be peopled with characters at various different stages, all interacting with each other ’s journeys. A character may represent a different archetype for some parts of the movie, but a dominant thread for one archetypal transformation is generally woven through the movie.

The Virgin, the Whore, the Hero and the Coward all represent the beginning stage of the three acts of life. Born into a dependent situation, every human must know who they are as an individual before they can reach their potential. Therefore, these four archetypes are concerned with the relationship a person has with oneself. It is the time for learning to stand on your own and take up your power.

The Virgin takes on the task of claiming her personal authority, even against the wishes of others. A big part of her story therefore is how she is viewed by society. Initially she is a valued commodity for being pure, untouched, good, kind, nice, compliant, agreeable, or helpful. She carries the hope for continuation of the virtues of a society. Through her journey she learns to redefine her values and bring her true self into being. She is well represented in movies like Bend It Like Beckham, Billy Elliot, and Shakespeare in Love.

The Hero takes on the task of expanding his boundaries in the world, at the risk of death. Driven by a desire to help his community, the Hero travels to a foreign land and learns to survive in and influence the big world. Classic Heroes are Neo in The Matrix and Luke Sky walker in Star Wars.

Together, the Virgin and the Hero represent the processes of knowing yourself as an individual, internally and externally. They also represent the two halves of having a relationship with your self: self-fulfillment and self-sacrifice.

From a power perspective, the Virgin and the Hero are moving from knowing themselves as dependent on people to knowing their own power. The Virgin gains the power to be all that she can be. It is the power to fulfill her greatest potential. The Hero gains the power to overcome his fear and shape and protect his world, even against the will of others.

The Virgin and the Hero represent the positive aspects of taking up individual power. Both separate themselves from the power structures they are born into such as being the daughter or son of… or the religious traditions of… and find a power they have earned through their own actions. The Virgin creates an emotional separation while the Hero separates himself physically from the people on which he was once dependent.

The Whore and the Coward represent the shadow side of failing to take up individual power. The Whore is caught in a life that ser vices the needs, values, and directions of others, to her own detriment and neglect. The Coward is so fearful of death that his life occupies a very small space.

The Virgin and the Whore carry the values of their community. As a shadow side, the Whore represents what is of low value. She is often seen as dirty, used, debased, weak, pathetic, and ruined beyond repair. Her sexuality is a metaphor for her spiritual essence or soul that is used in the service of others. The Whore is selling her soul to conform to the expectations of others. She is the scapegoat: blamed for all manner of sins and then run out of town literally or emotionally through the shaming and shunning of her and her bastard children. Societal judgments promote a downward spiral for the Whore into a complete loss of self and isolation, depression, insanity, or suicide. Anne Boleyn plays the Whore as she complies with her family’s plan to gain social power in The Other Boleyn Girl.

The Whore is selling her soul because she is completely out of touch with it or because she feels like a victim who lacks the power of an individual. The selling of the Whore’s soul does not have to be sexual. The husband who feels powerless to leave a self-destructive marriage because of low self-esteem, or the worker who hates her job because she has no personal expression also embody this shadow archetype. Belle in Beauty and the Beast plays the Whore when she exchanges her life for her father’s and then devotes herself to the transformation of the Beast (Zipes, 37).

The Coward fails to explore the world beyond his safe village and therefore has no confidence he can survive on his own. He lies, cheats, shirks, and bullies people to avoid being challenged in his ability to provide for himself. He avoids any thing that could lead to death or the fear of death or even hardship. Cypher (The Matrix) is the ultimate Coward when he betrays the last settlement of free humans because he wants the comforts of ignorance. He wants to be rich and have good food and a comfy bed. Raymond Shaw in The Manchurian Candidate (1962) is another good example of the Coward archetype where his notorious failure to separate from his mother makes him an ideal candidate for brainwashing.

These shadow archetypes are doomed to believe they must stay attached to other people to survive. The Whore believes she must appease or please people and is thereby a victim. The Coward believes he must control others to survive, and is a bully or an eternal child.

TABLE 1. Comparison of the Archetypal Features of the Virgin, Whore, Hero, and Coward

The Mother/Goddess, the Lover/King, the Femme Fatale and the Tyrant are the four archetypes who represent the middle stage of life, and all face the challenge of entering into a relationship with another. This is the search for the sacred union of the feminine with the masculine, at the risk of losing oneself.

The Mother/Goddess and the Lover/king know their power and must now enter into a relationship to use their power well and gain meaning in their life. This relationship can be between a man and a woman, a mother or a father and a child, and a woman or a man and her/his community. This union brings a form of wholeness.

The Mother/Goddess knows her power and is using her talent to nurture and inspire others, gradually depleting her resources. She must find a home for her power which rejuvenates her or she will burn out. To do this she must develop the art of receiving another into her heart and her life. Vianne, in the movie Chocolat, is seen as a threat to patriarchy as she brings sensuality and pleasure to her new village. When the battle for acceptance exhausts Vianne, the villagers open themselves to her ways and create a new type of community that embraces her. Pepa in Women on the Verge of a nervous Breakdown, Antonia in Antonia’s Line, Lotty in Enchanted April and Daniel in Mrs. Doubt fire all portray this essence of the Mother/Goddess archetype.

The Lover/king is challenged to surrender his heart to the feminine. However, attaching to the feminine renders him vulnerable to the mini-death of rejection if he is found unworthy, or to the vulnerability created by loving someone, providing his enemies with a means of inflicting death-like pain on him by harming his loved one. He also fears misplacing his love and meeting his emotional death at the hands of the Femme Fatale.

The Lover/king must face this fear, and even experience the death of some aspect of himself, in order to be reborn and have meaning and purpose in his life. In so doing, he becomes the dying and rising god. Through the experience of joining the feminine and the masculine or allowing love to become central to life, the Lover/king gains a form of immortality. He goes from living in black and white to living in Technicolor.

In Michael Clayton, Michael has an opportunity to acquire a large sum of money but chooses instead to expose evil and make the world a better place for his son. Michael rises above his past to reveal his better self to his son. In the movie Camelot, King Arthur must choose between standing by Guinevere, even when she has fallen in love with another man, or sacrificing her according to the code of his men. Arthur aligns himself with his men, the kingdom falls apart, and Arthur is a broken man.

The Bridges of Madison County, The Terminal, and Casino Royale contain strong images of the Lover/king archetype and his struggle with creating a relationship with the feminine.

The Mother/Goddess has the power to nurture, inspire, create ecstasy, and bring chaos. She uses her power to create growth and unconditional love in others. The Lover/King has the power to assert his will over others, even against their will, and bring integrity, order, justice, and security to his community. The Lover/King and the Mother/Goddess must come together to harmonize their powers to bring a balance of growth and stability, nurturance and justice, and receiving and offering.

The Femme Fatale and the Tyrant fail in the quest to join the feminine and the masculine by using people to preserve and enhance themselves. The Femme Fatale embodies a manipulative misuse of emotional power resulting in emasculation, dehumanization, and mistrust. These are all major impediments to entering into a loving relationship. In the movie Chicago, Roxie kills her lover, who told her he actually couldn’t get her into vaudeville, and tries to pin it on her husband, Amos. Amos believes his wife when she says the man was a burglar and willingly confesses to the murder. When he learns the guy has been visiting three times a week, he feels like a sap and rescinds his confession. Roxie accuses him of being a bad husband.

The Tyrant seeks to use his power for personal gain and is unfeeling towards the feminine. The Tyrant believes in transactional giving — he gives to get. He aims to control and dominate others. The Godfather movies enter the world of the Tyrant with murderous behavior in the name of the family. Codes stress the importance of respecting the Godfather’s dominance and superiority, and every interaction must give the Tyrant a benefit of status, respect, money, power, or future considerations.

The Femme Fatale and the Tyrant wish to maintain an imbalance of power. The Femme Fatale wants to emotionally manipulate the masculine until he is castrated. She sucks the life energy of others until they are dead. The Tyrant wants to assert his will over others to his maximum gain. He dominates a world of usury, rape, crime, violence, and patriarchal codes.

TABLE 2. Comparison of the Archetypal Features of the Mother/Goddess, Femme Fatale, Lover/King, and Tyrant

The end stage of life, the time of the Crone, the Hag, the Mentor and the Miser, sees the release of power and attachments to people and things and joining in relationship with the cosmos. The Crone and the Mentor spend their final days on earth releasing their power to leave a positive impact or discovering the beauty in their insignificance.

The Crone looks at the span of a lifetime and uses this perspective to recognize the growth people need to undergo when they can’t see it themselves. This growth initially appears to be a hardship, but eventually proves to be a transformation that makes life meaningful. The Crone’s abilities approach the magical as she moves towards releasing her body form and joining the spiritual world. She is the Trickster, using magic, intuition, and serendipity to drive people to face their flaws, as in Beauty and the Beast, where the old woman curses the Prince to be a beast until he learns to love and be loved in return. Fiona Anderson in Away From Her and Ninny Threadgoode in Fried Green Tomatoes also represent this journey of the Crone where the old woman places a friend in a situation that challenges the friend to grow.

The Mentor reflects on his life and evaluates his value to humanity. He looks for ways to leave a lasting memory of his time on earth after his physical body is gone. He endows gifts, builds monuments to things he values, supports causes he deems worthy and transfers his knowledge and wisdom to worthy recipients. He ensures the continuation of stability and good values through philanthropy, building, and mentoring and in this way gains a form of immortality.

The Hag and the Miser refuse to enter into a relationship with the cosmos. The Hag refuses to accept her unused potential and uses her magic to deny aging and confound the pathway of others. She may divert a Lover/king from his true destiny and into a hopeless union with her. Rather than contributing to the next generation, she robs it of a future. Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate is the perfect model of a Hag, as are Sheba Hart and Barbara Covett in Notes on a Scandal. The Hag is also the harbinger of doom, spreading a pessimistic message of the hopelessness of the future, as Hanna does in The Reader.

The power of the Hag is to cause stagnation in the personal growth of others. She cripples people with fear or interrupts their growth by using her magic to inhabit their lives. Brook and Mel in Thirteen are examples of the Hag who confounds the lives of teenage girls, consumed with efforts to appear young rather than fulfilling their mother role. Marquise Isabelle de Merteuil and Vicomte Sebastien de Vamont in Dangerous Liaisons also embody the Hag interfering in the lives of others for their personal amusement.

The Miser refuses to see the value of his accumulations to the greater community, even though power and material things are becoming of limited use to him. He hoards his wealth for himself and ignores the effect of his neglect on others. The actions of the Miser make his time spent on earth quickly forgotten. The classic example of the Miser is Scrooge in A Christmas Carol. The Miser also permit s ignorance, neglect, deprivation, and instability in the community. The father who is too busy working to engage with his children, as seen in movies like Thirteen and Liar Liar, embodies this archetype.

TABLE 3. Comparison of the Archetypal Features of the Crone, Hag, Mentor, and Miser

The Language of Symbols

Writers know the adage “Show, don’t tell.” This phrase points to a fundamental feature of archetypes: they speak through symbols. On-the-nose dialogue addresses the brain. Symbols address the unconscious and the soul of people, which is much more powerful and engaging than an appeal to the brain. Carl Jung recognized that archetypes are moved from our unconscious to our consciousness through symbols (Jung, 1976, 321), which explains why film is such a powerful medium for the expression of archetypal stories: it can be embedded with a wealth of symbols.

Metaphors are word images rather than words of direct meaning. In Billy Elliot, for example, the writer could address the brain with Billy saying, “I am struggling to find a place for my feminine energy which needs to be expressed through dance, and I need you to accept this part of me and not assume I’m gay. Mom would.” Instead we are given dialogue and images of Billy caring for and feeding his grandmother, who is under valued by the men; sitting at his deceased mother’s piano, trying to play the piano and being rebuffed by his dad; hating boxing classes, which his father highly values; coming alive in dancing classes; and watching his father bust up his mother’s piano to burn for heat. The words and pictures that speak symbolically have a much more powerful effect, even though they send the same message as the direct words. A symbol holds more meaning than words can explicitly state and opens up new avenues for understanding (Jung, 1976, 307).

Jung wrote, “Meaning only comes when people feel they are living the symbolic life, that they are actors in the divine drama” (Hollis, 2004, 11). This statement ties into another fundamental principle of screenwriting — audiences need a protagonist they can relate to. Virgins and Heroes are symbols for the universal need to stand on your own. When a symbol connects with the unconscious it generates energy that makes a person feel alive and ready to take on a transformation (Stein, 81). This is when character arc occurs. “When we resonate to this incarnated energy, we know we are in the presence of Soul” (Hollis, 1995, 9), and it gives the power to overcome hardship. The key to writing strong, relatable characters is finding symbols that personify the archetypes and make them recognizable.

The essential three acts of life appear in our culture as the trinities. They are the Holy Trinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, or the Celtic Trilogy of the Maiden, the Mother and the Crone. Each of these has a shadow counterpart, making twelve core archetypes. These essential archetypes can be known by many names. There may also be other archetypes that function beyond these twelve, but they represent the minimum a screenwriter needs to be familiar with. Table 4 includes examples of the range of male and female descriptive names in each category.

TABLE 4. Various Names Associated with the Twelve Core Archetypes

Archetypal journeys are not one-time events which occur at a certain age. Each time a social organization places someone at odds with their true nature, the Virgin archetype provides guidance towards becoming authentic. Any time something valued is threatened the Hero archetype may rise to save it. These moments can happen at any age and any number of times in a story.

Also, a character is not restricted to embodying a single archetype. The Virgin may play the Whore for a while, to emphasize the consequences of not realizing her dream. The Hero may play the Virgin as seen when a Prince is frustrated by the duties he is born to. Each archetype, however, represents a pivotal transformation and a protagonist generally follows one major journey.

Comparison of the Virgin and Hero

Virgin and Hero stories explore the theme of knowing yourself as an individual. Jung defined individuation as “the personal struggle for consciousness,” which begins with the understanding that you can exist as an individual (Stein, 174). The Virgin frees herself from dependency on her family of origin by connecting to her inner world. She expands her values to include her personal choice by developing her sensuality, creativity, and spirituality in a drive towards joy. The Hero achieves a sense of his ability to exist in the larger world by travelling to a strange land without anyone to provide food, shelter and safety for him and by challenging evil. He is learning to be brave, clever, skilled, strong, and rugged in a drive to overcome his fear of death.

The Virgin and the Hero story patterns are in many ways polar opposites of one another, two halves that make up a whole. Although they are both stories of learning to stand alone, the Virgin story is about knowing her dream for herself and bringing it to life while surrounded by the influences of her kingdom (Ever After). The Hero story is about facing mortal danger by leaving his village and proving he can exist in a larger world (Willow). The Virgin shifts her values over the course of her story to fully be herself in the world. The Hero is focused on developing his skills to actively do things that need to be done in the world. The Virgin is about self-fulfillment, while the Hero is about self-sacrifice. They represent the two driving forces in humans when faced with challenges: propelled towards the joy of being in harmony with yourself (Virgin’s journey); or driven away from fear to face hardship and conquer it bravely (Hero’s journey).

In Jungian terms, the Virgin must overcome her Father, or Ophelia, Complex, which is a need to please and conform to others’ values. Ophelia, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, is a young, sheltered girl who is used by her father to gain information about Prince Hamlet after he notices Hamlet is draw n to Ophelia’s beauty. A pawn to her father, superficially loved and later considered a whore by Hamlet, Ophelia eventually goes insane.

The Ophelia story illustrates the theme of how the Virgin must stop conforming to the wishes or beliefs of others or suffer greatly. Dependent on her father for love and security, and therefore unwilling to disturb his world of tradition, commerce, protection, and order, Ophelia adapts to her father’s values at the expense of her own.

The Virgin may even be proud to be useful to her father and enjoy his attention. Her over-identification with father-centered values will eventually leave her feeling empty until her own instincts towards creativity, sexuality or spirituality begin to rise. These feminine qualities make the father uncomfortable because they threaten his ordered world. The Virgin learns that she must place her own values and vision for her life ahead of those of her father (Murdock, xiii, 89) as seen in Bollywood /Hollywood and Billy Elliot.

The vision the Virgin has for herself could be a choice of lover, one who adores her rather than one who meets societal expectations of sexual orientation or social status (Broke back Mountain and Shakespeare in Love). She may dream of being a dancer, crusader, singer, soccer player, or boxer while her family, school or social class disapprove (Strictly Ballroom, Erin Brockovich, Bend It Like Beckham). She may have a spiritual need to reach for a sports achievement against impossible odds (Rocky, Angels in the Outfield). She must look inside herself and reach for her dream regardless of what others envision for her.

The Hero’s journey is the path to overcoming his Mother, or Oedipal, Complex, which is a desire to cling to the comforts of home at the expense of knowing the bigger world. In Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, Oedipus is a tragic character who inadvertently kills his father and marries his mother. This cautionary tale warns of the dangers of not separating from the place of origin.

The Hero must overcome his trepidations about leaving the warmth of the village, the metaphoric womb, and venture into the unknown to face his fear of death. He will only truly know that he can stand alone once he has proven himself in a foreign and inhospitable land. The Hero is motivated by the need to keep the village (or the maternal) safe but ultimately gains the knowledge that he has the skill to beat back death and live autonomously.

The differences between the Virgin and Hero themes illustrate the internal and external aspects of the process of knowing yourself as an individual. The Virgin emotionally separates from the people with whom she lives and creates a boundary between their values and hers while still living with them. The Hero physically detaches from the comforts of home and derives power from knowing hardship and developing skills. These archetypal stories show the path to becoming individuals, emotionally or psychologically and physically.

The Virgin and the Hero symbolize two aspects of knowing one’s place in the world. The archetypal journey takes the protagonist from one polarity to the other, from shadow to light. Growth initiates from the Whore or the Coward, and then follows a path into the Virgin and Hero journeys. Therefore, the Virgin begins her story lacking a sense of self, giving too much energy to the needs and opinions of others. In the end, the Virgin meets her need for self-fulfillment. By contrast, the Hero starts with a strong sense of self-preservation, refusing to get involved. Ultimately, he meets his duty of ser vice to others through self-sacrifice.

Another major distinction between the Virgin and Hero stories is the setting. The Virgin transforms within her kingdom; the familiar domestic setting where people assume they know what is best for her. This setting sets up the task for the Virgin to assert her vision for her life against the psychological pull of her community.

The Virgin does not leave her kingdom because her challenge is to face the influences of her domestic world whether they are physically around her or in her head. She finds a Secret World within her kingdom in which to practice her dream and grow in strength. At the same time, she meets the expectations of her Dependent World, keeping both worlds alive for as long as she can, fearful of discovery, yet joyful in her developing dream. If the Virgin does leave the kingdom, the internal pressures that limit her actions must be portrayed in some other way, such as flash backs or incidents that refer to an earlier influence that still affects her.

The Hero story is set in a foreign land — the more foreign, the better. It can be another country, galaxy or social status, but every thing he experiences is unfamiliar, such as habits, food, customs, and clothing. When he enters this land he is marked as an outsider, vulnerable to any number of unknown dangers. Danger is a key element because the Hero is pushing the boundaries of his mortality, exploring how far he can risk his life and still survive. Notably, the Hero has no feeling for the world he enters beyond fear and curiosity. He feels exposed, and there is no movement back and forth between the comforts of home and the hardships of his new surroundings.

The kingdom of the Virgin and the village of the Hero also undergo different experiences during the individuation of these characters. The kingdom is throw n into chaos by the Virgin and will undergo fundamental change as a result of her path. Usually, some aspect of the kingdom is causing stagnation among its people but they are so attached to order that they go along with an evil force or block individual growth to maintain it. The transformation of the Virgin will result in a change in the way people in her kingdom live, despite their initial resistance. The process of change usually occurs as a shift in attitudes or practices, rather than a physical destruction of property — unless, of course, the Hero shows up and eliminates an evil by force. In either case, this change will prove to be a benefit to the kingdom.

The Hero’s village, on the other hand, is seen as essentially good, if perhaps boring and too comfortable. It is worthy of preservation and will remain fundamentally unchanged, thanks to the efforts of the Hero. As the Hero undergoes his journey, the only change for the village is the elimination of the threat of danger. The foreign land doesn’t fare as well. While the Hero is in the foreign land, he is unconcerned about causing hurt feelings or property damage.

The kingdom of the Virgin represents the parts of a community that are in need of change. The village of the Hero represents what is good in a community and worth preserving. Together the actions of the Virgin and the Hero provide the balance of growth and stability in a community.

The obstacle in the Virgin story is the people around her who want to control her actions. The Virgin is not a volunteer in this adventure; rather, the plan for her life is the central theme. No one is encouraging her to take action: in fact, they are strongly discouraging it. While the kingdom wants her to be passive, the Virgin wants to actively pursue her own path.

In contrast, the village is the target of the evil in the Hero‘s journey. The Hero volunteers to battle this evil, making himself an obstacle to evil, but he is not the intended target. To emphasize this point, the Hero begins by refusing the call to adventure (Un forgiven and Romancing the Stone). The village wants the Hero to be active but he must volunteer to be self-sacrificing. In this way, the Virgin and the Hero have a very different relationship to the hardship that blocks their individuation processes.

The attitude of the Virgin and the Hero toward their obstacle is also different. The obstacle for the Virgin may be her love for the people of the kingdom, those who wish to keep her from changing. and it is their love for her that eventually brings change to their view of the Virgin and the kingdom as a whole. The growth of the antagonist out of love for the Virgin is often a major feature of the story. The obstacle does not need to be evil. It may be misguided, mistaken, overprotective or unknowingly living through the Virgin.

In the Hero story, the obstacle is evil. The Hero understands that it must be destroyed, neutralized, or eliminated. Things are separated more clearly into good and evil in the Hero’s journey. The antagonist usually does not grow in a Hero story: he is killed.

Stories of the Virgin and the Hero show ways to take up personal power. They do not, however, define power in the same way. The definition of power, according to sociologist Max Weber (which I would characterize as a masculine perspective), is “the chance for a man, or a number of men, to realize their own will in a communal action even against the will of others who are participating in the action”; or “the ability of a person to impose his will upon others despite resistance” (Wallimann, 231). Power is synonymous with control, command, jurisdiction, authority, and might.

This perspective on power is built around group control. The goal of the group takes precedence over the desires of an individual or a group asserts its will over another group. Sometimes the Hero asserts his will against a group but always on behalf of others. The Hero goes against evil, alone or with a group, asserts his will for the good of his village, and gains a sense of his power.

Another definition of power, put for ward in the video Women: A True Story: 2, The Power Game offers a feminine definition of power, which is more appropriate for the Virgin. The word “power” may have originated from the Latin word posse, which was defined as “to be all that we are capable of being.” This feminine definition of power is more individual-based and captures the essence of power in the phrase “the power of love.” It is about an individual fully coming into being, without imposing her will on others.

The Virgin pursues the art of fully “Being” and comes into her power when she sorts through all the seeds of her values and lives her life accordingly (Woodman, 78). She overcomes the masculine power that is controlling her, but not by doing battle with those asserting their will against hers. She reveals her inner self and inspires people to change through their love for her, their desire for the same autonomy, or the recognition of the value she brings. She and others are propelled towards change by the valuing of joy.

The quest of the Virgin is to become all she is capable of being and in so doing create joy and happiness. The quest of the Hero is to assert his will against evil and in so doing overcome fear. Becoming an individual is the process of coming into one’s personal power, in both its feminine and masculine aspects.

There is also a difference in the roles of the supporting characters within the Virgin and Hero stories. The characters in a Virgin story are people who are out of balance. The people she loves are often the ones blocking her from following her passion. These characters grow and change with the Virgin. Hero story characters are more dualistic, clearly either good or evil. The importance of the battle of good against evil is emphasized by the tragic death of minor, truly good characters, but overall, good triumphs.

Also, the Virgin has old friends while the Hero has new allies. In the Virgin story there is often a childhood friend who stands by the Virgin and unconditionally loves her. The girlfriend in Working Girl or Maid in Manhattan and the family servants in Ever After are typical of the Virgin supporting characters. The friends are ref lections of the Virgin’s value, foreshadowing her potential from an early stage.

The supporting characters in the Hero story are allies met along his journey who share the common goal of defeating evil. Classic examples include the Tin Man, Scarecrow, and the Cowardly Lion in The wizard of Oz or Princess Leia and Han Solo in Star Wars. Their bond is based on their common mission. It is not necessary that allies like each other as long as there is mutual interest.

Two other archetypes, the Mentor and the Crone, have similar functions in both stories. They give that extra help that tips the balance in favor of success for the Virgin or the Hero. The Crone uses magic or trickery as the High Aldwin does in Willow and the boy with the mouse does in Shakespeare in Love. The Mentor provides tools, wisdom and knowledge as Gandalf does in Lord of the Rings and Morpheus does in The Matrix.

The tensions are also different in the Virgin and Hero stories. The cost of the Virgin going on her pathway is the potential loss of love, joy, and passion. Without these things that accompany the fulfillment of her dream, the Virgin suffers loss of self, which manifests as depression, insanity or suicide. The cost to the Hero of going on his journey is potentially death. This loss of life at the hands of others will involve physical pain and leave his village vulnerable to evil.

Both stories follow an emotional pattern in which the protagonist is at first tenuous, then takes a chance and almost loses, but learns from this experience and finally follows the pathway to success. In short, they both go through emotional reversals that make for great story telling.

TABLE 5. Comparison of the Virgin and Hero Stories