Читать книгу Eldritch Manor - Kim Thompson - Страница 4

Chapter One

ОглавлениеIn which our heroine goes out to seek her fortune in the world, but finds only old ladies and scrapes her knees

As she tumbled over the handlebars of her bike, twelve-year-old Willa Fuller decided that this had to be the absolute worst day of her life so far.

It was the first day of summer vacation, a day she’d been eagerly anticipating for months. The sun shone down on her small town, the birds sang, the children played, but Willa was in a “slough of despond” (a lovely phrase she’d read somewhere). And falling off her bike was the least of her troubles. Everything had gone wrong from the very start of her day.

At breakfast her bread got caught in the toaster and burned and smoked and stank up the whole kitchen. Then her mom came in, waving aside the smoke without comment, which was a sign something grim was in the offing.

“Something grim is in the offing,” announced Willa, because she liked saying old-fashioned words like that, but also to make her mom smile. Her mom did not smile. Another bad sign.

“Willa,” she said flatly, “you won’t be staying with Grandpa this summer.” Grandpa lived in a tiny house right on the ocean, and every summer Willa went to stay with him for two or three weeks. She looked forward to it all year. Just a short drive from town, the seashore seemed like another world. At Grandpa’s she didn’t have to worry about being cool or popular, she could read all day if she liked, or wander up and down the beach looking for treasures, and she always, always found something good. But what she liked most of all was that Grandpa always treated her like a grown-up.

“Is he all right?” Willa asked anxiously.

Her mom smiled, nodding. “Grandpa’s fine, don’t worry.”

Willa hated “serious” talks like this. You just didn’t know what terrible thing was coming next. Her mom looked down at the table and went on.

“It’s just that things aren’t going so well, and we thought maybe you could get a summer job here in town and help out.”

Willa was stunned. All she could do was nod as her stomach turned right over. Things not going well? Were they broke? She guessed it had to do with Grandpa. He himself admitted he was the worst fisherman in the world. He said his good luck had left him the same time Willa’s grandmother had, long ago when Willa’s mom was still young. Whatever the reason, while his friends hauled in catch after catch of wriggling fish, Grandpa’s nets always came up empty. He now made his living by renting his boat to tourists and fixing traps and nets for the other fishermen. It wasn’t much of a living, and Willa knew Mom and Dad sent him money to keep him going.

Willa stared down at her burnt toast as all this ran through her mind. She wished Dad was there to back her up, but he’d already left for work. Her mother briskly brushed the toast crumbs from the table. “Don’t your friends work in the summer? I always had a job when I was your age.”

Willa shook her head. “They go to camp mostly. Nicky’s at camp, Flora’s at camp. Kate’s at the cottage with her cousins.” It wasn’t her friends’ fault they went away for the summer, Willa knew, but she still felt abandoned.

Her mother barely registered what she’d said. “Well, anyway ... I’d like you to go see Hattie at the Tribune today. She said she’d try to find a job for you there. Delivering papers at least. It’s not much but it’ll be a start.” Her mom rose, smiling. “Your first job! Isn’t that exciting?” And she breezed out of the kitchen, not waiting for an answer, and not registering the utterly miserable look on Willa’s face.

So on what should have been a gloriously free first day of summer, Willa unhappily pedalled over to the newspaper office. Climbing the front steps she caught sight of her reflection in the glass door. She looked so awkward, all bony knees and skinny arms, in second-hand clothes that didn’t fit properly. Her curly hair stuck out in all directions. And to top it all off she was slouching, which always made her mom yell at her. She made a face. Then she thought about Grandpa, took a deep breath, pulled herself up straight, and went inside.

The newspaper office filled her with dread. It was easy for her mom to talk about getting a job, like it was the simplest thing in the world, but dealing with strangers, especially grown-ups, just made Willa anxious. Her mother was calm, clear, and forceful, always in control, but Willa ... Willa panicked, Willa mumbled, Willa dropped things and stumbled over her own feet whenever someone was watching. Willa only felt comfortable when she was alone, reading and daydreaming. Or when she was with her grandpa at the seashore, but of course now that was off the agenda. Instead she was here in a loud and busy newspaper office full of vaguely alarming grown-ups.

Willa inched up to the front desk and asked for her Aunt Hattie. She had to ask four times because the receptionist couldn’t hear her over the ringing phones and people talking. Aunt Hattie was Dad’s older sister. She was tall, huge, really, with five or six pencils always stuck and forgotten in her frizzy hair. The same frizzy hair Willa had, from Dad’s side of the family. Hair that did the opposite of what you wanted it to, that defied gravity, and doubled in volume whenever it rained.

Now Hattie and her hair emerged from her office and loomed over Willa. She had the scowl of a person who is very busy and wants you to know it. “Willa,” she said flatly, “we’ve got all the carriers we need.” Willa smiled with relief, but Hattie wasn’t finished. “But I do have a spot in sales. It’s commission work. That means you only make money if you sell subscriptions. Take it or leave it.”

It didn’t seem that “leave it” was really an option. Hattie didn’t wait for an answer but loaded Willa up with sample papers, an order book, and a list of the addresses of people who didn’t subscribe to the Trilby Tribune but should. It was now Willa’s solemn duty to talk them into changing their ways.

As Willa loaded the papers into her bike carrier, she reflected gloomily on her fate. She hadn’t even wanted to deliver papers, but now that seemed like the best job in the world compared to knocking on doors and talking to strangers all day.

From that low point the day proceeded in a downhill direction. As Willa covered street after street, rang doorbells, and gave away sample papers, it became increasingly apparent that she was a terrible salesperson. When she launched into her “sales pitch” her mouth dried up and her voice became so thin and quavery that no one could hear what she was saying. She had to repeat herself over and over until the words got all tangled and she sounded like an idiot.

After a full day pedalling around in the dust and heat, she hadn’t sold a single subscription, and she only had one more house on her list. It was the big house backing onto the ravine, the old rambly one that was twice the size of all the other houses on the block. Willa used to imagine that someone fabulously wealthy and glamorous lived there, until her mom told her it was a rooming house for seniors. After that the old place just hadn’t seemed so interesting anymore.

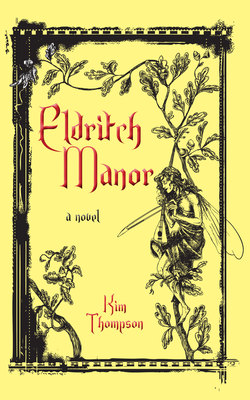

She paused in front under a weeping willow. There was a small sign on the gate that she’d never noticed before, obscured by vines. It said “Eldritch Manor.” Willa peered up at the house. It seemed too grand a name for such a tired-looking place, with its weathered, peeling paint and the porch sagging under its own weight. Still, the house had a kind of weary dignity, with its gabled windows and turrets and little balconies. There was even a widow’s walk on the roof. The place sure had more character than her house, a boring modern little bungalow. She longed for a widow’s walk. If they had one she’d be up there all day. She’d stare out toward the ocean and pace tragically. She’d pretend she was waiting for someone to return after years and years of agonizing separation. It would sure beat selling newspapers.

She climbed the front steps to the porch where two old ladies were snoozing in the sunshine. One was lying on a sofa, her round, smiling face tilted toward the sun and one short leg dangling. She was rather rotund and didn’t so much lie on the sofa as flow across it, like she had no bones. An empty cat food tin was balanced on the arm of the sofa, which was scratched to ribbons, but there were no cats in sight.

The second lady sat in a wheelchair with a blanket covering her legs. Her beautiful silvery hair fell all the way to the floor behind her, glinting in the sunshine like tinsel. She too was a little large and fleshy, but her hands in her lap were long and narrow, and her face was thin and delicate. She would have been positively elegant had it not been for the snuffling, snorting, and wheezing issuing from her open mouth as she slept. Willa paused on the top step and cleared her throat. No one stirred. She tried again. “Excuse me? Hello?”

The round lady on the sofa opened one eye and squinted at her. “Hmmm?” she purred. Willa nervously started her pitch. “I’m here ... the Trilby Tribune ... you don’t ... would you like ... I’m selling subscriptions....”

The lady didn’t speak or even move, she just watched Willa with that one open eye, which made Willa even more nervous. She took a deep breath and started again.

“I’m selling subscriptions to the Trilby Tribune, would you like to subscribe?”

She held out a sample paper. The lady slowly closed the one eye and began to stretch, first one arm then the other, then a leg then the other leg ... all the while yawning great gaping yawns without even covering her mouth. Willa waited — what else could she do? Finally the old lady sat up straight and opened her eyes, both of them this time. She reached over and poked the lady in the wheelchair with one long, curved nail.

“Belle! Wake up! You’re snoring again!”

Belle started awake, snorting a little. She scowled. “I do NOT snore, you mangy old beast!” Then she noticed Willa. Her face rolled back into a big smile and her voice smoothed into honey.

“A visitor. How lovely. Why didn’t you wake me, Baz?” Baz snorted and rolled her eyes as she settled back onto the sofa. Belle gestured for Willa to come closer.

“I’m selling newspaper subscriptions, ma’am.”

Belle didn’t seem to hear her. She was too busy looking her up and down. Her stare grew more and more intense, and Willa felt a sudden chill. Belle’s eyes were like marbles, all swirly blue and green. And Willa suddenly noticed how pale she was — white as a sheet, practically.

“I know you,” the old lady finally announced, sitting back serenely. “I know you better than you know yourself.” Great, thought Willa, crazy lady alert. She tried again. “Would you be interested in sub —”

“Tell me something, dearie,” Belle interrupted, taking Willa’s hand in her own, which was cool and smooth as a stone. She smiled sweetly. “Do you have a car?”

Eyes closed, Baz cautioned in a singsong tone, “Miss Trang will heeear youuuu.”

Belle waved her off, but her voice dropped to a whisper as she leaned closer, fixing Willa with her watery eyes. “Do you have a car, sweetie? Could you take a helpless little old lady to the seashore?” She batted her long lashes.

Willa shook her head. “I don’t — I can’t drive. I’m only twelve.”

Belle’s mood changed once more. “Well, that’s just great!” she snapped, dropping Willa’s hand, her eyes now icy. Baz had leaned over and was sniffing at Belle’s sleeve. Belle shook her off. “Stop it! For goodness sake!”

Baz curled up on the sofa again, smiling dreamily. “I can’t help it. You smell so nice ... like tuna.”

It was true, but Belle was outraged. “I do not, you fool!” she shot back.

“Do too!”

“Do not!”

“Do too!”

“Liar!”

“Fishy smelling fishy fish!”

“Fleabag!”

“LADIES!”

Willa jumped. A woman stood in the doorway, looking at them sternly. She was ... smooth. General impression, smooth. Willa couldn’t tell how old she was — she seemed much older than Willa’s mom but her skin was smooth, no wrinkles at all. Her hair was smoothed back into a bun. Her clothes, a very simple skirt and shirt, were dark grey, boring, and smooth.

“She started it,” growled Belle, crossing her arms sulkily.

“I didn’t. She called me a fleabag, Miss Trang.” Baz gave Belle a smug smile. Belle stuck out her tongue. Miss Trang ignored them and turned to Willa.

“Who are you? What do you want?” Her voice rolled out effortlessly, like oil. Smooth. Willa couldn’t even tell if she was being friendly or unfriendly.

“I’m ... um, selling ...”

Miss Trang cut her off brusquely. “We’re not interested, but thank you for dropping by.”

Willa looked back at the ladies. Belle was sulking. Baz seemed to be asleep.

“Goodbye,” prompted Miss Trang. Definitely unfriendly now. Willa mumbled an awkward goodbye and hurried down the steps, just glad to be leaving. She picked up her bike and put the sample paper in the carrier. Zero sales. She was officially the worst salesperson in the world.

“Psst!”

Willa turned to see Belle waving her back, her bony fingers rippling through the porch railing. Miss Trang had disappeared inside, so Willa tiptoed through the flowerbed until she was directly below the old lady, who was smiling again.

“Darling child, do see if you can get me a ride to the seashore, will you please?”

“But I told you I —”

“Just try. I’m sure you can manage something. Give me your hand.”

Willa held up her hand. Belle flicked her long white fingers and a stream of coins suddenly appeared, dribbling from her hand into Willa’s. Neat trick, she thought.

“I can’t take this,” she protested, but Belle cut her off. “It’s for that, whatever you’re selling....”

“Newspapers.”

“Yes, whatever. Now go on, before she sees you.”

Willa needed no more prompting. She made a quick exit, dumping the coins into her pocket, where they now jangled as she fell forward over her handlebars, shortly after her front wheel hit the curb in front of the news-paper office, the one curb in town that is half an inch too high, which is precisely where we came in.

After a short, uneventful flight, she landed on the sidewalk, rolling and scraping her palms, elbows, and knees. She lay for a moment with her cheek on the hot pavement. Her eyes teared up. Her hands stung horribly but her first thought was — did anyone see?

She looked up and sure enough, just her luck, there were some grade nine boys across the street, outside the corner store. They were laughing. One of them said something she couldn’t hear and the laughter doubled.

Willa blinked back tears as she sat up and inspected her palms. Why couldn’t she have broken her leg? Then she could spend the summer in bed with a giant cast and read all day instead of getting a stupid job. Pulling up her left knee for a closer look, she heard some of the coins slip out of her pocket onto the sidewalk with a soft clink. She turned to see them rolling away, which immediately struck her as odd because they were rolling uphill. She quickly put out a foot to stop them.

The three coins abruptly stopped and executed a smart right hand turn, curving around her foot and continuing on their way up the sidewalk.