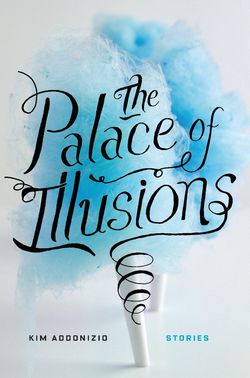

Читать книгу The Palace of Illusions - Kim Addonizio - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBEAUTIFUL LADY OF THE SNOW

Annabelle puts her hand in the water and scoops out one of the goldfish she got at the county fair. The other one leaves its little red and green castle to float up against the glass and watch. The fish flips over a few times on the counter. Annabelle doesn’t want to hurt it; she only wants to stroke the shiny gold with her finger. But the fish flips so hard it sails off and lands on the floor next to her shoes, the new black patent-leather ones she got for First Communion. It doesn’t look gold anymore, down in the shadows by the cupboard. She picks it up; it is quick and alive in her hand, its mouth opening and closing, trying to suck in air. Suddenly it wriggles free, flying away. She steps back, startled, and feels it squish under her heel.

She squats down to look. The head is flattened, a little liquid oozing from it. She gets a paper towel and crumples it around the fish, the way she has done with spiders. Then she puts it in the trash can under the sink, hiding it beneath a coffee filter full of wet grounds.

When Annabelle’s mother comes into the apartment from the motel office, Annabelle is sitting on the couch with her feet straight out, watching TV over the shiny tops of her shoes. She wears them in the apartment all the time; her mother doesn’t want her to scuff them by wearing them outside, except on special occasions.

Annabelle’s mother manages the motel, and they get a free apartment behind the office. Annabelle’s mother also has to take care of Grandpa, who lives in a trailer a few miles away and needs to go everywhere in a wheelchair with an oxygen tank. Grandpa can walk, when he needs to, but it is easier for him to ride, Annabelle’s mother explained. Sometimes Grandpa makes Annabelle ride on his lap, and Annabelle hates that, hates sinking into the fat thighs, the smothering arms wrapped around her. Plus, he smells like an old cigar. Even though he is not supposed to smoke anymore, she knows he sits in a green plastic chair outside his trailer and does just that. The cigar butts are right there, in a Maxwell House can, and it is filled nearly to the top.

There are two good things about Grandpa’s place. One is the white cat that lives in the woods behind his trailer, that will run up to eat the food Annabelle sets out for it on a napkin, as long as Annabelle stands far enough back. The other is that Grandpa will let Annabelle have sweets, though it is sort of a good and bad thing at the same time. Grandpa says he intends to spoil her rotten, and Annabelle understands this to mean that one day all the chocolates and Cokes and Oreos her grandfather has given her will turn her insides black and hollow, like the picture of a decayed tooth the dentist showed her. Not only her teeth are going to rot, but her whole body. Sometimes Grandpa will sneak a candy bar into her plastic Barbie purse, for later. It is a secret between them, something her mother doesn’t know.

“Lord in Heaven,” her mother says, coming over to the couch to sit next to Annabelle. “I’m sweating like a pig.” She is wearing a white sleeveless blouse and shorts that show the purple veins on her legs. Her face is splotched with red. She wipes it with a washcloth and then uses the washcloth on each armpit. The couch is old, the worn cushion sinking under her weight. Annabelle moves to the other cushion and draws her knees up. If her feet touch the floor, the scaly monster that lives under the couch will drag her under.

“Having fun, baby?” her mother says, touching Annabelle’s hair.

Annabelle shrugs.

“At least you got the air-conditioning.” The apartment is cool, but in the office there is only a big fan that turns back and forth, pushing the hot air around. Her mother licks her thumb, then uses it to rub at a spot of dried milk on Annabelle’s chin. Annabelle scowls and tries to duck, but her mother holds her head firmly with one hand until the milk is gone.

“There,” her mother says. “Now you’re pretty.”

This is what Grandpa says when Annabelle puts on makeup for him. She brushes on powder and blush and red lipstick and glittery blue or green eye shadow that he bought for her at Rite Aid. She holds her long hair up like a glamorous model, and he tells her to get herself a piece of chocolate from the refrigerator, and to pour him some of his Ballantine whiskey. She twists the ice out of its tray carefully, into the freezer bin, and refills the tray. Then she puts three ice cubes in the glass and fills the glass. She chooses a chocolate, taking a few minutes to decide, trying to guess which one is the caramel and which is the cherry or the coconut or, best of all, the one with more chocolate inside. If she dances for Grandpa she will get another piece, and if she brings him a second glass of whiskey he will go to sleep, and she can eat whatever she likes.

It is the end of July, a month before second grade. In June Annabelle went to day camp, where she went swimming in a pool and made several ceramic ashtrays with lopsided scallops. But camp was too expensive to go for the whole summer. Now she has nothing to do all day but sit in the air-conditioning and watch TV, the curtains closed against the hot bright sun. Or she can play in a corner of the lobby with her Barbies, while the phone rings and grownups go in and out asking for the plastic cards that open the doors or pouring themselves coffee from the pot that sits on a burner all day next to the rack of brochures for the caverns. The caverns are the big attraction here, the only thing around that people might want to see, though Annabelle has never been there. The brochures show damp stalactites and rock walls that have folds in them like blankets. The visitors’ children kick at the chairs in the lobby or grab handfuls of brochures and stare at her. They take butterscotch candies from the dish on the counter, which she is not allowed to have, filling their mouths and their pockets and dropping the wrappers on the floor. Annabelle is not allowed to pick up the wrappers, because they have germs. According to her mother, germs are everywhere, waiting to make you sick.

Annabelle is allowed to go behind the counter and sit at the big desk but not to answer the phone. She has a plastic one that she puts on the desk. She picks up the pink receiver and answers, “Burnside Motel,” in a professional voice. She pretends her Old Maid cards are key cards, and she hands them out to her Barbies and tells them how to get to the different rooms and where they should park their cars. She explains that there are three places to eat in town—a Denny’s, an Arby’s, and Sue’s Kitchen—and that Denny’s has the best hamburgers but Sue’s has really good fried chicken.

“Do you want to come sit with me in the office?” her mother says.

“Nope,” Annabelle says. The TV show is interesting, cartoon mice in their furnished mouse hole with its arched doorway, backing away from a big orange cat’s paw that is poking in. Annabelle holds her breath for a second, but the cat can’t get to them.

“Mommy,” she says. “Can I get a mouse?”

“A mouse! Hell, no. Mice are dirty. They carry germs.”

“I want one,” Annabelle says, jutting out her lower lip.

“You want a mouse,” her mother says. “And what if the mouse gets loose? What if it runs into the office, or one of the rooms? We’ll be out on our asses in ten minutes. No way you are getting a mouse, Missy.”

On TV, the mice are tiptoeing into the kitchen, toward a big wedge of swiss cheese in a mousetrap.

“What about a gerbil?” Annabelle says.

Annabelle doesn’t remember her father, who left when she was a baby. The man she thinks of as her father is the one who lived with them when she was in preschool and kindergarten and part of first grade. It’s Joe she remembers, standing at the open kitchen window blowing smoke out into the white-flowered bushes bordering the motel, putting his cigarettes out one by one in the seashell ashtray on the sill. Joe used to read to her—stories about how the leopard got its spots and the loon got its necklace. He fixed the things that broke at the motel, the bathtub drains that clogged and the heaters that wouldn’t come on. Now another man does that, but he doesn’t live with them. Joe left, and there hasn’t been anybody since, because, as Annabelle’s mother explained to her, most men are good for nothing pieces of shit, who can’t appreciate a quality woman.

Since Joe left, her mother has gotten almost as big as Grandpa. There are no sweets in the house, but there is lots of bread, kaiser rolls and English muffins and loaves of Wonder. There are boxes of macaroni and cheese that come in spirals or rounds, and family-sized bags of Fritos and pretzels and Ruffles and Pringles. Her mother can eat a whole tube of Pringles just during Wheel of Fortune. She snacks all day long in the office, too. At night, when she thinks Annabelle is asleep, she cries.

Annabelle lies in bed holding Simba, her stuffed lion, listening to her mother’s sobbing. Usually Simba can comfort her, but tonight he seems indifferent to her troubles—her fears of rotting all over from too much candy, or of burning in hell, where her mother says all the bad people burn, her worry about her mother who is going to die of loneliness unless a man touches her soon and she gets some loving. Tonight Simba does not seem to care that as each day passes there is no man and no loving and her mother is one step closer to dying. Simba is king of the jungle, the most powerful animal, and he can do anything when he wants to.

“Help,” Annabelle whispers, but Simba seems to be sleeping. Annabelle hears her mother hang up the phone, then the crackle of a chip bag being opened. She puts both hands around Simba’s neck and squeezes hard, but his eyes just shine at her blankly and she knows he is not going to come out from behind them.

It’s a few days before Annabelle’s mother notices that there is only one fish in the bowl on the kitchen counter. It is Annabelle’s job to feed the fish; every morning and evening she has been shaking the flakes of food onto the surface of the water and watching the remaining one rise to the surface, its mouth open and working to catch them.

“Where’s the other one?” her mother says one morning.

Annabelle shrugs, trying to be casual. She lifts a spoonful of Cheerios carefully to her mouth. Inside her chest, she can feel her heart flipping like the fish did, before she squashed it. She would like to tell her mother what happened, but maybe her mother will get mad, and then she will shake Annabelle, hard, spank her, and send her to her room.

“It flew away, I guess,” she says.

“Well,” her mother says, “I’m surprised they lived this long. Those things usually go belly-up in a week.”

“Oh,” Annabelle says. Her heart quiets, floating.

When her mother goes into the office, Annabelle returns to the bowl. She puts her index finger to the glass, and the fish swims to it, looking at her.

“Here, fishie,” Annabelle says.

It swims away, returns. In a video Annabelle watched last night, a whale was captured and put in an aquarium, and then some children helped it get back to the ocean. She doesn’t know where the ocean is, though, only that it’s far away from here. She goes into the living room and sits on the couch for a few minutes, but she keeps thinking about the fish. She turns on the TV to distract herself, but the kitchen counter is just beyond the TV, and all she can see are the gold fins waving back and forth, the small beads of its eyes looking at her, asking her to set it free.

She thinks a minute, then goes over and climbs up on a stool. She takes the bowl in both hands, moving slowly so the water won’t slosh over the sides, and carries it into the bathroom. She sets it on the floor and reaches her hand in and takes out the little castle. Then she dumps the water and the goldfish into the toilet bowl. She watches it swim around there, then goes to watch TV for a while and forgets about it.

When she has to pee, though, she remembers. She goes in and pulls down her jeans and underwear, and sits on the toilet. But she is afraid the fish will jump up and bite her vagina, maybe even swim up in there, so she gets up and flushes the toilet, making sure the fish is gone before she sits back down. She takes the bowl back to the kitchen, fills it with water from the sink, and puts the little castle back in the center. It will be a day or two, probably, before her mother notices, and then she can say it went belly-up and she had to throw it away.

Annabelle and her mother and Grandpa are at the Walmart, getting a new wooden folding table so Grandpa can sit on the couch and eat in front of the TV the way he likes to. He fell over the old one and broke it. He is always breaking things, dropping dishes, falling over furniture.

Annabelle’s mother pushes the wheelchair while Annabelle walks behind them. She drifts back farther and farther, stopping to examine a wooden mousetrap that looks just like the one in the cartoon, only without the cheese. There are roach motels and ant powder, cans of Raid and Black Flag. Annabelle has seen her mother spray the lines of ants that sometimes crawl in, along the floor and up the wall; when she finishes, the ants are dark specks her mother wipes away, and the air smells sticky and sweet.

When Annabelle looks up, her mother and Grandpa have turned the corner. She heads to the part of the store she likes best, where the finches and parakeets are. The birds live in a big, square mesh cage with several trapezes for them to perch on. She likes the bright colors of their feathers and the sounds they make and their round black eyes that reflect the fluorescent lights of the store. She loses track of time, watching them. Then the loudspeaker calls a Code Adam, which Annabelle knows from a TV movie means that the employees are supposed to look around for an unattended child. In less than a minute a boy with a shaved head and dirty fingernails is there, dragging her up front to the checkout counters. Her mother is standing with her arms crossed against her chest, looking angry at the world. Grandpa is asleep in his chair.

“You scared the crap out of me,” her mother says in her quiet voice that is scarier than her loud voice. She kneels down to take Annabelle by the shoulders and starts shaking her. “Look at me, dammit.”

Annabelle shifts her gaze to the ground, focusing on her mother’s sandaled feet, on the chipped scarlet polish of her toes. She feels that if her mother looks into her eyes, she’ll be able to see the two goldfish, swirling around there the way the second one did before it was sucked down into the toilet bowl. She will be able to see Annabelle in her Little Mermaid underwear, made up like a model and dancing for Grandpa, her face and hands smeared with chocolate.

Finally she thinks of something she saw on a different TV movie. She looks into her mother’s face and says, “I am fatherless.”

Annabelle names the parakeet Sam. Her mother bought it for her that day, and they even stopped at the Dairy Queen on the way home. Sam is blue and green and yellow. He sits in his cage on the coffee table during the day, chirping and ringing a little bell, and at night Annabelle puts the plastic flowered cover over the cage.

“Now, isn’t that better than a gerbil?” her mother says.

“I don’t know,” Annabelle says. “Can I still have one? Can I have a cat?” She thinks about the white cat that lives in the woods near Grandpa. It is a thin, bony thing that slinks out from the trees and streaks away if she moves toward it. She has named it Snowbelle, which means Beautiful Lady of the Snow, even though she doesn’t know if it’s a boy or girl. It hasn’t let her get close enough.

At church that Sunday the priest talks about the Holy Spirit. There’s the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The Father is away in heaven, and the Son died for everyone’s sins, and the Holy Spirit is a dove that flies around, and comes down into you where you have an empty jar inside you, and it fills up your jar. If you don’t get the Holy Spirit, you are a sinner and will burn up in hell. Annabelle imagines that hell looks like the caverns she has never seen, filled with dark damp spaces and black bats with fangs flying upside down trying to bite her face off. But there is something thrilling about hell, too, about the idea of going down deep inside a cave and not coming back up, hiding down there where no one can find her, where she can live by a river that looks and tastes like Coke, and all her Barbies will lie naked in a circle around her because she is the Queen Beautiful Lady Anna, and the pieces of shit men will be there and won’t be able to leave because they are chained-up slaves. And if Joe is stuck down there she will use a big bucket to pour water on him so the flames don’t hurt so much.

But what if Grandpa is there, too, with his oxygen tank, wetting his pants? Annabelle looks around the church. She needs to get the Holy Spirit right away. But all she sees are the pews filled with people, and light through the stained glass windows above them, and Jesus hanging on the big cross in his diaper, looking like he is asleep.

After church they go to Sue’s Kitchen for lunch. Annabelle is wearing her pink dotted Swiss dress and Communion shoes, and her mother is dressed up and has used rollers in her hair so it has waves in it. Her mother orders Salisbury steak and gravy. Annabelle gets fried chicken and is allowed to have lime Jello for dessert. She drinks her milk with a straw, blowing pale white bubbles into the glass.

“What a sweet little angel,” someone says.

Annabelle looks up. A man is standing next to their booth, a big pink-cheeked man with a neat black beard and no hair on his head. He has large, fleshy lips that make her think of the wax ones the Walmart sells at Halloween.

“She sure is a beauty,” the man says, but he is looking at her mother, not Annabelle. He leans both hands on their table, meaty hands with big hairy knuckles and long fingers and—she counts them quickly—six rings.

“Sweet!” her mother says. “Stubborn as a mule, is what she is.”

Annabelle is surprised by how her mother says it; her voice is soft as a melted butter pat.

“Her mother ain’t bad, neither,” the man says. His voice is a butter knife, slipping in easily, smearing the butter around on soft bread.

Annabelle slides down the back of the leather booth until her feet are way under the table and her head is on the seat, and squinches her eyes shut.

“You raising her alone?” the man says.

“With God’s help.”

This is the first Annabelle has heard about God helping out.

“I can’t say I’m a believer, myself,” the man says, “though sometimes I figure there must be something else out there. I mean, all that space, there’s got to be, right? Even if it’s only little green men with bug eyes.”

Annabelle’s mother laughs, and Annabelle pictures green men the size of ants, crawling out of an anthill.

“I envy those who have faith,” the man says.

“Well, to each his own,” her mother says. “I believe everyone should get along.”

“I wouldn’t mind getting along with you,” the man says, and Annabelle thinks about the green man-ants swarming up the ramp into Grandpa’s trailer, crawling along his wheelchair and into his eyes and nose and ears, starting to eat him alive.

The man stands there talking to her mother for what seems like forever.

“I have to pee,” Annabelle says. Her mother just waves her hand, so Annabelle goes by herself. When she comes out, the man is gone. She follows her mother out to their van.

“He’s going to come by the motel,” her mother says. “He usually stays at the Days Inn, but they don’t have free HBO like we do, and all they serve for breakfast are bad donuts, and we have those cinnamon buns from Sue’s. Do you want one tomorrow? You can have one tomorrow.” Her mother babbles on, the way she did when she was taking those green and white pills to help her stop eating. They didn’t work; she just ate and talked all day and cried harder at night.

When they get to the motel her mother goes back to work in the dress she wore to church, instead of changing into sweatpants and a T-shirt like she usually does, and Annabelle leans forward on the couch looking at Sam in his cage, poking her finger in to touch him.

The man comes that night, through the door at the back of the office and into their apartment. Annabelle spies on them from her bedroom, her door cracked open. They are on the couch together, laughing. The man has on a T-shirt, thick dark hair all down his fat arms. One dark, ugly arm is around her mother’s shoulders. Her mother lets her head fall back, and the man pours beer from the bottle into her mouth.

“Atta girl,” he says. “Shit, you can hold it.”

Her mother sits up, reaches for a bottle on the table. There are a lot of bottles. Her mother’s legs are open, her dress hiked up. Annabelle watches the man put his own beer on the floor, watches his hand disappear under her mother’s dress. Her mother squirms, then pulls his hand away.

“Not here,” she says. “My kid—”

“She’s asleep,” he says. He unzips his pants, leans close to her ear, and says something.

“You’re filthy,” Annabelle’s mother says.

Annabelle thinks about filthy germs.

But her mother is laughing. “Not now,” she says. “Later—”

“Okay,” the man says. He reaches for his beer on the floor and knocks it over. “Hell,” he says. “Sorry about that.” He looks at Sam’s cage on the table, the plastic cover over it. He pulls the cover off.

“Where’s the bird?” he says.

Annabelle is being punished for letting Sam out of his cage. She is not allowed to watch TV for three days. She told her mother that she wanted Sam to be free. She didn’t tell her that he had bitten her finger, that she had unlatched the door and put her hand in to grab him, then run to the bathroom sink and turned the water all the way on and stuck him under the faucet. She felt his small body, his heart beating frantically in her hand.

“You’re bad,” she told him. “You’re bad and you have to be punished.”

He struggled and thrashed in the water, splashing her face and arms.

“I think you’re sorry now,” she said. “I think you’re sorry and don’t need to be punished anymore. And just remember, don’t try to fly away.”

But when she lifted him up he wouldn’t move. She patted him with a dry washcloth, but he stayed sodden and still. She wrapped him in the washcloth and rocked him back and forth. Finally she carried him outside in her pink Barbie purse and buried him around the side of the motel where she isn’t supposed to go, where there is nothing but a field of dead grass and an abandoned gas station where the high school kids leave empty beer cans and candy wrappers and cigarette butts.

Now Sam will be with her in hell, by the river where the goldfish will swim back and forth like tiny flickering pieces of fire. There is no way she will get the Holy Spirit now. She doesn’t care about not watching TV; she sits in her room, holding Simba, rocking him the way she did with Sam. Simba knows all about Grandpa, but he won’t help her.

In the afternoon she runs errands for her mother, brings her Diet Mountain Dew and Fritos from the apartment, and by the end of the day her mother has forgiven her.

The man is in room 220, just upstairs from them. No one ever stays here more than a night. They check in one day, and the next day they are gone, to someplace where there is more to see than some caves in the ground.

“You’re staying at Grandpa’s tonight,” her mother tells her.

When the night clerk, Jolie, shows up to relieve her mother, Annabelle has packed her pajamas and toothbrush and clean underwear and Simba and two Barbies in a plastic bag. Her Barbie purse is over her shoulder. In the purse is a tube of Cherry Chapstick, a pair of yellow sunglasses with daisies on them, some butterfly hair clips, and one blue feather that belonged to Sam.

On the drive over her mother talks nonstop about the man, whose name is Jim. Jim is a hoot. Jim likes to watch baseball and hockey. Jim sells office supplies right now but he could sell anything, anywhere, even something here in this town. Jim is a miracle from heaven, God has finally heard her prayers, and Annabelle should pray that he stays so she will no longer be a fatherless little girl.

Annabelle doesn’t want to pray. Jim isn’t her father; Joe was, but Joe has gone and she doesn’t know where. When he left, he forgot to say good-bye; she had watched his pickup turn out of the parking lot, and waited for him to remember and turn around, the way he often turned around because he had forgotten his glasses, or forgot he didn’t have any money to take her for an ice cream and had to go back and get some from her mother. Sometimes they would get as far as Denny’s before he remembered, and he would whip a U-turn in the middle of the road and then she would run in and get the glasses or money or his cigarettes, and run back to the truck. Maybe Joe will remember one day that he forgot Annabelle, and will come back for her in his truck that smells like cigarettes and air freshener, and they will go away and be married.

“I don’t want to go to Grandpa’s,” Annabelle says, as soon as her mother pulls out onto the road.

“Tough titties, baby,” her mother says. “Your old mother’s got a date.”

“He smokes cigars,” Annabelle says. “I think they have germs.” She tries to think of what else she can say, to get her mother to turn the car around.

“Those cigars are going to kill him for sure,” her mother says.

The trees go by on both sides of the road. They are tall, so tall it’s hard to see the top of them. Annabelle wishes she were a tree, with her feet planted firmly in the dirt behind the motel and her head sticking into heaven.

“I dance for him,” Annabelle says finally.

She wants to take it back as soon as she says it, because her mother’s face changes right away, and she pulls off abruptly into a gravel turnoff and jams on the brakes.

“What do you mean?” her mother says. “What do you mean, you dance for him?”

“Nothing,” Annabelle says, looking down into her lap.

Her mother has her by the shoulders. “You dance for him,” her mother repeats.

“Is it a sin?” Annabelle says.

She thinks about doing the hula in front of Grandpa, to the music she has to imagine in her head. She thinks about her arms moving from side to side, like waves in the ocean, wherever it is. She thinks of climbing into a boat that is too small for Grandpa and his wheelchair. A whale will tow her out to sea, a rope from the boat looped around its tail.

“I do the hula,” she says.

“Oh,” her mother says, looking into her eyes.

But Annabelle feels, now, that her mother can’t see anything there, that she probably doesn’t want to see anything—not the fish, not Sam, and not Grandpa watching her dance, drinking his whiskey.

“Be careful,” her mother says.

“Yes, ma’am,” Annabelle says.

At Grandpa’s, Annabelle watches whatever Grandpa watches; tonight it is one of the crime shows he likes. There is a little girl about Annabelle’s age, but she isn’t really in the show, only her picture; she has disappeared, and the police are trying to find her, talking to different grownups and to the girl’s teenaged babysitter.

A commercial comes on, a big expensive car going fast down a highway toward some mountains in the distance.

“Fix me another drink,” Grandpa says.

He has been saying this for a while now, drinking fast. Annabelle hopes that means he is going to fall asleep soon. She goes and makes him another one. She sees the new box of chocolates in the refrigerator when she opens the freezer for ice.

“How about a little dance from my girl?” Grandpa says, when she brings him his whiskey.

“It’s my bedtime,” Annabelle says, which it is. She is already in her pajamas. She yawns, opening her mouth wide, stretching her arms up.

“Aw, c’mon,” Grandpa says. “Pretty please with Hershey’s syrup on top.”

“I don’t like chocolate anymore,” Annabelle says.

“Oh, sure you do,” Grandpa says. “You love it. My favorite little girl,” he says. “My little girl loves chocolate.”

“No, I don’t,” Annabelle says.

“You listen to your Grandpa,” he says. “Do what I tell you.”

“No.” She remembers her mother saying, Stubborn as a mule to the man in Sue’s Kitchen. “I hate chocolate,” she says. “And I hate dancing and I hate it when you wet your pants, so there.”

Grandpa looks at her a moment. Then he says, “You spoiled little brat.” He looks really upset. Annabelle has never seen him like this before. He has always been nice as pie, smiling at her, giving her treats and presents, asking her for dances. “Get over here right now.” He starts to rise from the couch, but sinks back down, wheezing and red in the face.

“I need my oxygen,” he says. His tank is in the bedroom. “Go bring it in here.”

“No,” Annabelle says.

“Now!” Grandpa says.

This is a Grandpa she has never seen, angry and needing his oxygen.

“I won’t,” Annabelle says.

“Oh, yes you will, Missy.”

He is breathing more slowly now, his face returning to its normal color. Again, he starts to get up from the couch. But before he is even off it, she has run out the door of the trailer and down the ramp.

“Get back here,” Grandpa calls.

But Grandpa is old, and slow. By the time he is at the door, she is running through the woods in the dark, branches stinging her face and arms.

When she can’t run anymore she stops, panting. She looks back toward the trailer, at a light pole on the road she knows is nearby. She can’t actually see the trailer, or Grandpa. Maybe he has gone back to get his tank from the bedroom, to sit on the couch and watch his show. Or maybe he is in the plastic chair in the dirt yard, smoking one of his cigars. The cigars will kill him one day. Her mother said so. Every day, Grandpa will get older and slower, and Annabelle will get bigger and stronger. If he chases her, Grandpa will wheeze and turn red in the face. The next time he asks for his oxygen, she will hide it, and he won’t be able to catch his breath. He will take in the air in little gasps, and then he will pass out for good, and be perfectly still. Then Annabelle will disappear, like the girl on the crime show. No one will be able to find out where she is. She will live in the woods in a fort, just her and Simba and the white cat Beautiful Lady of the Snow. Annabelle has never seen real snow, but she knows that somewhere, like at the North Pole, it falls all the time, covering the ground and trees and buildings, making everything it touches white, and pure again.