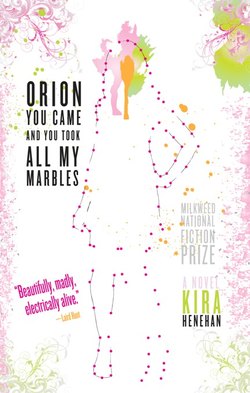

Читать книгу Orion You Came and You Took All My Marbles - Kira Henehan - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

Whereupon such tedium, offered an inch, begs mightily, mercilessly, for a yard, and I am compelled to gesture—with a great and profound reluctance, somewhat wishing reports had never been started—toward that great tedious time between my waking and today, rendering, one can only hope, further digression unnecessary.

So:

Murphy came after I was already there. He came of his own accord.

I too may well have come of my own accord; I may always have been there, but Murphy definitely was not always there, and as far as I can ascertain was not summoned/dragged/blackmailed/et cetera. I remember the day he came. It had not been sunny then either and, as would make sense, he did not carry any smell of sun about his person.

Whence the sun smell.

I wonder.

I also digress. From the digression itself as it were. He came and he was absorbed without formality into us. Maybe he had been expected. Binelli introduced him to me as Murphy. He didn’t look like a Murphy, like what I at least would expect a Murphy to look like. And apparently I didn’t look much like a Finley to him, because when Binelli introduced us (Murphy, Finley; Finley, Murphy), Murphy said,—Finley?

And Binelli said,—Sure, why not?

So.

When Binelli had retreated behind his door, Murphy stared and stared at me. I was made slightly anxious by this, until I realized the probable cause.—My eyes, I acknowledged.

He nodded quickly.

—Are yellow, I finished.

—Yes, he said.

—I don’t know why, I said.—They just are.

—Yes, he said.

Then he said,—It’s very unusual, yellow eyes.

Then he said,—Why do they call you Finley.

—Why do they call you Murphy, I answered, not really answering, having ultimately no surefire explanation.

—I suppose, he said,—it’s my name?

He said it like a question and looked at me closely. For what, who knew. Perhaps an answer. Perhaps not. The eyes I am aware can be distracting. Binelli had said so at least. The Lamb had as well, had in fact on several occasions pronounced them nightmare-making.

—Try not to look at them, I offered.—If they bother you.

—They don’t bother me, he said.—Finley, he said. He shuffled something in his pockets which was, I would soon come to learn, a regular thing he did. Stick his hands in his pockets and jangle around in there. And rock a bit back and forth, and look down at the ground, and hum a little three-note tune. All these things he did on a regular basis. A nervous set of habits I supposed.

—Okay then, Finley, he said, pronouncing my name with what I may or may not be paranoid in assuming to be a touch of distaste.

It’s not a terrible name. It’s not something, at least, I can help. I was named, as people generally are, and the naming forces were beyond my control.

Did I mention yet that Binelli made me a Russian? By way of my papers, he did. He did that knowing full well my feelings on the matter. This is important to say now because Murphy asked where it was from, Finley.

I said I didn’t know, but my papers made me Russian. And then he laughed and laughed and laughed.—Russian? he said over and over.—Russian?

And then he stopped laughing all of a sudden and said,—That figures, and then that was all for our first conversation. We’ve had many since then. And with the tyrannically needy tedium thus appeased, there I’ll let the digression end.