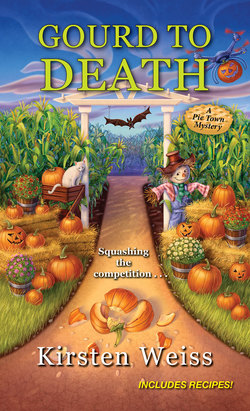

Читать книгу Gourd to Death - Kirsten Weiss - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Six

It was dark when I awoke at my usual ungodly baker’s hour. Yawning, I grabbed a Pie Town T-shirt, slipped into a pair of jeans, and brushed my hair into a ponytail. I made myself peanut butter toast, jammed it in my mouth, shrugged into a Pie Town hoodie and staggered out the door.

The light above the tiny house’s door flipped on, illuminating the picnic table and my delivery van.

I stumbled to a halt. The toast dropped from my mouth.

Someone had tagged the Pie Town van in shaky black text that read: FULL OF BALONEY.

I picked up the toast, which had naturally fallen peanut butter-side down, and walked around the pink van. There was more. The words COFFIN VARNISH Scarred the rear doors. And on the other side, VAL HARRIS IS A FLAT TIRE.

Flat tire? What did that even mean? I checked the tires. Nope. Not flat. And coffin varnish? I vaguely remembered that had been an insult in the dark ages of the early twentieth century.

This was the weirdest graffiti ever, and in other circumstances, I might have laughed. But this was the official Pie Town delivery van. I couldn’t drive around town with this stupid graffiti. How much was getting it repainted going to cost?

I stomped around and cursed, because it made me feel better and no one could see.

Beside the picnic table, I stilled, my skin crawling. Was whoever had painted my van watching?

The automatic light over my door switched off, bathing me in darkness.

I ran back to my shipping container/tiny home. The light over the door snapped on again.

Heart pounding, I scanned my yard from the tiny home steps. The shadows seemed to shift, and I blinked rapidly. I must be imagining that watchful feeling. But my house was out of the way, at the end of its own winding dirt road. This wasn’t a crime of opportunity. Someone had driven here and targeted me with oddball graffiti.

I ran back inside, grabbed a flashlight, and returned to the van. If the paint was wet, this had been done recently.

Swallowing, I touched the graffiti.

Dry.

Relieved, I pulled my hand away. Black smeared my fingertips.

Huh?

I rubbed my fingers together. The stuff felt chalky. I ran my finger through the graffiti, drawing a pale line.

I hurried inside and retrieved a rag from beneath the kitchen sink. The clock on the miniature stove blinked, baleful. I was going to be late.

But I trotted to the van and scrubbed. The graffiti came off, and a rush of relief flowed through my veins. A good car wash would probably remove any remaining traces.

I stepped from the van and studied its pink sides. No permanent harm had been done. Had the graffiti been a practical joke? But by whom?

It didn’t seem like the gamers’ style.

Charlene’s? But if she’d done it, she’d have stuck around to crow over my reaction.

Locking my house, I jumped into the van and bumped down the dirt road, descending into a bank of fog.

Soon, I was pulling into the misty brick alley behind Pie Town. A light shone through one of the small, high windows in the kitchen, and I grimaced. I hated being the last person to get to my own business.

I hauled open the heavy, metal door and strode into the kitchen. “Sorry I’m late,” I shouted over the roar of the mixer.

Petronella looked up from a counter full of apples in various states. With her gloved hands, she adjusted the net containing her spiky black hair. “What happened?”

Abril switched off the heavy mixer. Her brown eyes widened with concern. “You’re late. Is everything okay?”

My face warmed. It was the first official day of the pumpkin festival. Tardiness was a high crime, or at least a misdemeanor. “Someone graffitied the van. Fortunately, they used chalk.”

“What a lame prank,” Petronella said. “Who would go all the way to your house to chalk a van?”

“Maybe Charlene’s up to her tricks.” Abril angled her head toward the flour-work room. Odd mechanical noises emerged from behind the closed, metal door.

“Yeah.” My brow furrowed. The language on my van had recalled flappers and ragtime. But I couldn’t see Charlene doing something so pointless. Not on the first day of the festival.

I knocked on the metal door. “Is everything okay in there?”

The whirring fell silent. “I’m fine,” Charlene called. “Busy. Aren’t you?”

“Yes, but did anything odd happen last night?” I pulled open the door.

“You’ll ruin the temperature control,” she shouted.

I released the handle as if scalded.

“And what do you mean by anything odd happening?” she called through the door. “What do you think I get up to after I go to bed?”

“Nothing, but—”

“Nothing? There could be something. I’m not a monk, you know.”

Ugh. “Never mind.”

I snapped on a hairnet, tied on an apron, and ran a round of dough through the flattener. Roughly, I slipped it into a pie tin and turned it, pinching the dough around its edges. A murder had been committed yesterday. Was there a connection between that and the graffiti? It didn’t seem likely I’d become a target because I’d found the body. Two different criminal minds were likely at work—one deadly, one dippy.

At six, I hauled the coffee urn to the dining area and turned the sign in the glass front door to OPEN. I set the day-old hand pies on the counter.

Aged regulars trickled into Pie Town for self-serve coffee, cheap snacks, and gossip.

As much as I wanted to hear what they thought about Dr. Levant’s murder, I had about a dillion autumn pies to bake. I’d decided to go heavy on the pumpkin, for obvious reasons. But there were other fall favorites, such as apple-cranberry, mincemeat, sweet potato, and pecan. The festival menu also included Wisconsin harvest pie, tart cherry, a maple-pumpkin with salted pecan brittle, and pumpkin chiffon.

Insides jittering, I hurriedly filled piecrusts. This would be one of our biggest days of the year. There was no margin for error.

Gordon and three uniformed cops presented themselves for duty at nine. The tables were already nearly full of early festival arrivals grabbing coffee.

Tally-Wally sat beside the urn. He explained how the self-serve basket worked, ensuring there were no java scofflaws.

Outside, the fog had begun to lift. It blanketed the rooftops and revealed giant black spiderwebs strung across Main Street.

I explained our system of numbered tent cards to the cops. The cops would take the orders for people standing in line and speed things along. I just hoped we were busy enough to justify the system.

“A word, Val?” Gordon nodded to the hallway. Even Gordon was in uniform blues today. He looked even hotter in them than in his usual detective’s power suit.

“Sure.” Who can resist a man in uniform?

Gordon followed me into the hallway and stopped me with a hand to my arm. I turned, and he was close, so close I could smell his bay rum cologne. He lowered his head, his emerald eyes intent.

My heart beat more rapidly. “Maybe we should go into the office,” I said in a low voice. His colleagues might see.

“You’re right,” he said. “And we need Charlene.”

Charlene? “Um, what exactly did you have in mind?”

Gordon’s handsome brow furrowed. “What did you?” His expression cleared, and he laughed shortly. “Oh. Not that.”

Kissing me quickly, he zipped into the kitchen, the door swinging in his wake, and returned with my piecrust specialist. Charlene looked like an autumn leaf in her orange tunic and brown leggings.

So much for a romantic interlude. I followed them into my utilitarian office.

Gordon shut the door behind us, and the VA calendar on its back fluttered. “Thanks for sending me those crime scene photos, Charlene.”

“You took crime-scene photos?” I sat against the metal desk and folded my arms. “When?”

She shrugged. “When you weren’t looking.”

“I need your help,” he said. “I can’t get anywhere near this case—not officially.”

Charlene leaned against the closed door, rumpling the VA calendar. “It goes without saying, the Baker Street Bakers are at your disposal.”

“Great.” He looked around the office. “Have you got a whiteboard?”

“Why would we have a whiteboard?” Charlene asked.

“It’s fine.” He grabbed paper from the printer tray and rummaged in my desk.

“Can I help you?” I asked, bemused.

“Got it.” Extracting a roll of tape, he taped five sheets to the wall behind my desk. “I know you haven’t had time to take those PI courses, so I’m going to give you a crash course.”

“PI courses?” Charlene asked, looking intrigued.

He wrote across the five sheets of paper and tapped the first page that said EVERYTHING. “One, you need to document everything in your murder book.”

“We do keep case files,” Charlene said. “We’re not total noobs.”

“Everything.” He underlined the word and pointed to the next sheet: TIMELINE. “Next, we need to nail down the timeline. When exactly did Dr. Levant die? Where were all the suspects at the time?”

“Her partner, Tristan Cannon, was setting up their festival booth that morning,” I said. “But we don’t know when Dr. Levant died or when exactly he arrived.”

“Let’s not get ahead of ourselves,” he said.

Charlene straightened off the door. “But you asked about the suspects.”

“Before we decide who the suspects are, we need to talk to potential witnesses.” He numbered that three on the paper. “And that includes talking to everyone who was on the street at the time the body was discovered.”

“Everybody?” I squeaked. That seemed like a lot of work. And speaking of work . . . I surreptitiously checked my watch. I needed to get back to the kitchen.

Charlene yawned. “Boring.”

“This is how an investigation is conducted,” he said.

“That’s how the police conduct an investigation,” she said, “not us.”

“We need to follow every lead.” He turned to the wall and marked that number four. “And treat everything you discover as evidence.” He wrote EVIDENCE on the final sheet of paper.

I folded my arms. One of the benefits of having your own business is there’s no one above you to tell you what to do. I wanted to help Gordon. Being taken off the case was obviously bothering him. But, well, Charlene and I had been in charge of the Baker Street Bakers too....

Charlene squinted at the wall. “Everything, timeline, evidence . . . ETE? What kind of acronym is that? You work for the government. You people are supposed to be coming up with acronyms all day long.”

“It’s not an acronym,” Gordon said.

“It should be,” she said. “If you want us to remember anything, you need an acronym like SNOT or WHAM or BANG or something. Whiteboards. Huh! I’ve got to get back to my crusts.” She strode from the room. The door banged shut behind her.

“We’ll help in any way we can,” I said. “Like we always do.” I could think of him as a client.

“She’s right. This is wrong.” He scraped his hands through his hair. “What am I doing?”

“Educating us. It’s interesting.” Okay, that was a lie. “We can stand to be more organized in our amateur investigating. It’s just that . . . organization and Charlene aren’t really the peanut butter and chocolate of the investigation world.”

He scrubbed his hands across his face. “Crazy. I’m going crazy. That’s all. And why wouldn’t I be? I’m San Nicholas’s only detective, and yet I’m the only detective in Silicon Valley who never detects.”

“That’s not true. You’ve solved all sorts of crimes.”

He glared. “Yesterday I stopped a surfer stampede.”

“A what?”

“They were trying to knock down the new gates a spoiled techie put up. They were blocking public access to the beach.”

“That’s . . . that must have been interesting.”

“It was a job for a beat cop.” He blew out his breath. “And not your problem.”

I rested my hand on his arm. “Gordon, if it’s your problem, it’s mine too. Consider yourself our number one client.”

“Client?”

“Charlene and I will let you know everything we discover. But I’m going to be working this festival all weekend. And my stepmother turned up, so I’ll probably be spending time with her on Monday if she’s still around.”

“Your stepmother?”

“She surprised me yesterday.” I laughed weakly. “But she seems nice.”

“How are you doing with it?”

“It’s family, I guess. The more the merrier, right?”

He pulled me against his chest. “Thanks for putting up with my temporary insanity.” He drew me into a bone-melting kiss, his hands exploring the hollows of my back.

We broke apart, breathing heavily.

“Oh,” I said, my lips burning.

He grinned. “And thanks for doing this. Helping the Athletic League, I mean.”

I forced my breathing to steady. “Did I mention you’ll have to wear an apron?”

He quirked a brow. “You think that bothers me?”

I laced my fingers behind his neck and leaned against him. “No. I’m sure your manhood will remain intact. Plus, they’ve got pockets for your tips.”

“Always thinking.”

“I may have another non-murdery case for you.” I ran my hands down the front of his pressed shirt. “Someone put graffiti on my van last night while I was sleeping. It all came off, but it’s kind of weird.”

“It came off? Did you take any photos?”

“Uh, no. I was so freaked out about having to take the van to the festival with that stuff on it, I forgot.”

“What did it say?”

I told him.

He laughed. “Charlene?”

My glance flicked to the dented office door. “I don’t think so. It made me late, and she wouldn’t do that on the first day of the pumpkin festival.”

“No, she wouldn’t.” His brow furrowed. “I don’t like that someone made the trek all the way to your house. You’re pretty isolated on that bluff. But it sounds like a prank. It could have been kids trying to get to that cemetery.”

“What cemetery?”

“The one behind your house.”

I stared. “What cemetery behind my house?”

“You know, behind your place, down the hill. It dates from the eighteen-hundreds. Now it’s so covered in brambles and poison oak, most people don’t bother with it.”

“You’re pulling my leg,” I said flatly. It had to be a Halloween joke. “Did Charlene put you up to this?”

“You didn’t know?”

“No!” He really wasn’t kidding. “I never go down that hill. I don’t want to get poison oak.” And why the devil hadn’t Charlene mentioned a graveyard when she’d rented me the house?

“It’s just an old cemetery.”

“Right.” I stepped away from him and pulled some aprons from a box. “Your uniforms. Excuse me. I’ve got to have a chat with my landlady.”

I stormed into the kitchen and yanked open the door to the flour-work room. “A cemetery? Behind my house?”

A ghost of cold air flowed into the kitchen.

Charlene patted dough into a round and dropped it onto a metal tray. “Oh, yeah. It’s real historic.” Stooping, she brushed flour from her brown-and-orange striped socks.

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“What does it matter?” she asked, arch. “You don’t believe in ghosts, remember?”

“That’s not—” I sputtered. “You should have disclosed!”

“California law only requires disclosures of deaths on the property within the last three years. Those corpses are over a century old, and they’re not on my property.”

“Oooh!” But there was no point being mad. The only real surprise was freewheeling Charlene hadn’t held a ghost hunt in my backyard. But not even Charlene fooled around with poison oak.

Abril poked her head into the flour-work room, her white net puffed high with her thick hair. “They’re coming,” she squeaked. “It’s a mob. I’ve never seen so many—”

“We’ll talk about this later,” I said to Charlene. “Abril, breathe.”

She bent, taking deep, gusty breaths.

Charlene shrugged.

I hurried into the kitchen. A roar of voices flowed through the order window, and I looked out.

A maelstrom of pumpkin-starved festivalgoers flooded into the dining area.

If it hadn’t been for the cops, there might have been a riot. But our new system for taking orders in line seemed to work. I wasn’t sure if the customers were charmed or cowed by the aproned police officers. But there was no shoving or sniping.

I worked harder than I’ve ever worked—we all did. Even Charlene stayed beyond her usual piecrust-making hours to run the cash register.

Around three o’clock, Charlene whistled through the order window into the kitchen. “Val, you got a visitor.”

The kitchen’s swinging door bumped and swayed but didn’t open.

I jammed a plate of pumpkin chiffon pie through the window. “Who is it?”

Charlene set the pie on the counter. A cop grabbed it, whisking it to a table.

“Open the door,” Charlene said.

Shaking my head, I bustled to the kitchen door.

It bumped open, and a pumpkin zipped between my legs.

I yelped.

Gears whirring, the pumpkin jounced onto the black fatigue mats. It twirled in a tight circle.

“Remote controlled!” Charlene cackled through the order window. “I’m sure to win the pumpkin race this year.”

I peered at the spinning pumpkin. Someone had mounted it on what looked like miniature tank treads. “Did you make this?”

“Ray built it. He owed me one.”

The pumpkin circled Abril, and she squeaked, jumping.

It raced to my feet. The contraption’s metal arm extended an order slip.

I plucked the slip from its mechanical claw. Charlene’s uneven script scrawled across the yellow paper: Your stepmother is here. “Thanks.”

“De nada.” Charlene pulled her head from the order window. “Oh, they changed the race time. I’m going to be a little late to your pumpkin judging.”

Rats. That meant I wouldn’t be able to see the races either. I would have liked to cheer on Charlene.

Peeling off my plastic gloves, I hopped over the pumpkin and hurried through the swinging door to the dining area.

Takako had jammed herself into a corner between a pink booth and the counter.

I glanced nervously at the sign that proclaimed MAXIMUM CAPACITY: 100. But I knew the cops would be watching that sign too and making sure we didn’t violate any fire codes.

“Takako!” I wiped my hands on my apron and searched the crowd for Gordon. He wasn’t there. “It’s nice to see you again. Do you want to come into the kitchen?”

She drew her hands from the pockets of her San Nicholas Pumpkin Festival jacket and hugged me. “I can? I’m allowed?”

“As long as you don’t mind wearing a hairnet. And don’t mind the robot pumpkin.”

Takako stepped away and bumped into a hipster with a beard a lumberjack would have envied. “I had to wear a net in the fish cannery, and I think your pumpkin is escaping.”

The pumpkin motored through the crowd, eliciting shrieks, laughs, and jumps.

I tugged down my apron. “Charlene, control that thing.”

Obediently, the pumpkin pivoted. It motored under the Dutch door and stopped beneath Charlene’s chair, behind the register.

Charlene leaned from her seat. “You worked in a fish cannery, Takako?”

“In Alaska,” she said. “But only for one summer.”

“So did I.” Charlene retrieved Robo-squash and set it on the counter. “I can’t stand salmon anymore.”

“Neither can I!”

“Or sea monsters,” Charlene said. “Damned Tizheruks. One snatched Sam right off the dock in Ekuk.”

Takako’s brow crinkled. “Tiz . . . ?”

“Why don’t you come on back?” I nodded toward the gently swinging door. “We can talk while I plate pies.”

Takako followed me into the kitchen.

I grabbed a hairnet from a box atop the old-fashioned pie safe and handed it to her.

Takako snapped the net over her wavy black hair.

“This is my assistant,” I said, “Abril. Abril, this is Doran’s mom, Takako.”

Abril smiled shyly and cut slices of apple-cranberry pie. “Hello.”

While Takako and Abril got acquainted, I grabbed a ticket from the wheel in the window.

The pumpkin chiffon was popular. I plated another slice and slid it through the window.

Takako leaned against a metal counter. “Your business is booming, Val. Your mother would be proud.”

An ache pinched my heart. “I’m sorry she never got a chance to see Pie Town.” We’d plotted and planned it out before she’d died. Her insurance money had even gone into the start-up. A part of her was here, in spirit.

Charlene, followed by her rolling pumpkin, ambled into the kitchen. “Still working, I see.” She fiddled with a black control box. The pumpkin ground to a halt beside the haint-blue pie safe.

I slid a slice of harvest pie onto a plate and set it in the window. “What else would I be doing today?”

“You haven’t taken a break all day.” Charlene’s forehead scrunched. She maneuvered the robot arm upward.

Abril shot Charlene an indecipherable look.

“I don’t mind skipping breaks during the pumpkin festival,” I said. “I had a mini turkey pot pie for lunch.”

“Eating on your feet while you work isn’t a break,” Takako scolded.

“That’s what I said,” Charlene said. Her robot knocked the box of hairnets to the floor. Moving creakily, she retrieved the box. “Petronella, Abril, and the coppers have got it handled. I’m old. I need a break. So do you.”

Abril nodded. “Have your lunch break, Val. Get out and enjoy the festival.”

“But I don’t—”

“It’s settled.” Charlene pushed me toward the alley door.

Giving up, I stripped off gloves, hairnet, and apron. “Fine,” I said, “but only if we go to the haunted house.” I loved haunted houses, and it would have made me sick to miss this one. Plus, Dr. Levant’s husband, Elon, had worked there. I doubted he’d be there the day after his wife’s murder. But maybe one of his colleagues could tell us where he’d been the morning his wife had been killed.

“There’s a haunted house?” Takako asked.

“In the old jail,” Charlene said. “The church does it up every year for charity.”

The robot bumped after her.

“You can’t bring that to the haunted house,” I said.

“Why not?” Charlene asked. “I can afford the ticket. And I need to test it under adverse conditions.”

“You know,” Takako said, “I’ve never been inside a haunted house. Not a fake one I mean.”

“You’ve been in a real haunted house?” Charlene asked.

“That’s what the locals claimed,” my stepmother said.

I grabbed my orange-and-black hoodie from a hook on the door and followed them outside. The foggy air was a pleasant slap to the face. I inhaled deeply, scenting salt from the nearby Pacific.

Charlene and Takako ambled down the alley, the pumpkin racer zipping ahead.

Since this was more harvest festival than spooktacular, the decorations were mostly pumpkins, pumpkins, and more pumpkins. Pumpkins stacked beside doorsteps. Pumpkins on hay bales. Minipumpkins in shop windows. At least there was no question of mismatched colors.

Off Main Street, the town had set up wooden photo cutouts designed from vintage Halloween postcards. Grinning tourists stuck their heads through the holes, transforming into old-fashioned witches and devils for the camera. A tractor towed a wagon full of hay bales and tourists down one street.

We passed a bouncy castle full of shrieking children. Teens putted in a minigolf graveyard. Toddlers hugged goats in a petting zoo. The goats mehhed, weary expressions in their big brown eyes.

Private homes had gotten into the spirit too. Pumpkins lined porch railings, and witches on broomsticks crashed into trees.

We stood in line for tickets at the old jail, a square, concrete building. Above its green doors a placard read: JAIL, BUILT 1911. The haunted house was actually in the more sizable red barn at the rear.

I looked at the clock on my phone.

“Stop checking the time and enjoy the moment.” Charlene maneuvered the pumpkin around a stroller. The toddler hung over its side, watching the pumpkin fly past. “It’ll be over all too soon.”

I blew out my breath. Easy for her to say. I was responsible for Pie Town and payrolls.

“How’s Frederick doing?” I asked Charlene, changing the subject.

“Frederick?” Takako asked. “Have you got a gentleman friend?”

“My cat,” Charlene said. “And he’s hiding at home. He hates pumpkin.” She smiled. “But I might have a gentleman friend.”

Was she getting serious with Ewan? The two were perfect for each other. He even owned a fake ghost town. I opened my mouth to ask, and the racer made a sharp turn beneath my feet. I stumbled, scowling.

“Whoops,” she said. “Sorry.”

The line moved quickly, and soon I was handing over cash for tickets for the three of us. I had to buy a child’s ticket for the pumpkin.

A tall, middle-aged man with thinning brown hair stepped from the jail. He smiled wearily at the ticket seller. “I’ll take over now, Gladys.”

“Elon?” Charlene grasped his hand. “What are you doing here today? I was sorry to hear about your wife. What a terrible loss.”

“Thank you, Charlene.” Lines fanned from the corners of Elon’s eyes, owlish behind tortoiseshell glasses. He nodded, his aesthetic face somber, his tarnished eyes haunted. “Hello, Val, and is that pumpkin moving?”

“My entry in the race,” Charlene said.

“And this is my, er, this is Takako Harris,” I said. “Please accept my condolences on your loss. Kara was a wonderful doctor.”

He studied his tennis shoes. “Thank you.”

“What can we do to help?” Charlene asked.

“Nothing.” He looked past my shoulder, his gaze unfocused. “Kara was such a planner, she had everything organized, even for her death. Now, I’ve got nothing to do, except think. And I don’t want to think, not today.” He swallowed convulsively. “They said I should stay home. But I’d already taken today off to volunteer, and I didn’t want to sit home alone. And now I’m talking too much. That’s what comes from being a salesman, I guess.” He touched his eyeglasses. “I talk.”

My chest pinched with sympathy. I wasn’t sure what to say that wasn’t a platitude.

“Such a stupid prank,” he continued. “Kara’s death was meaningless.”

“Prank?” I asked.

He blinked and focused on me. “The pumpkin. She must have been trying to stop some foolish sabotage.”

“You think she was killed because of the pumpkin,” I said slowly.

“What else could it be? She didn’t have enemies.”

“Everybody has enemies,” Charlene said.

“Not Kara,” he said. “Her biggest rival was Laurelynn Lelli, and that was nothing.”

“Laurelynn?” I asked. She was wholesaling our mini pumpkin pies this month at her organic pumpkin patch.

“They went to high school together,” he said. “She owns the pumpkin farm on Lincoln Way. They were always bickering about something. It was silly.”

“Anything lately?” Crumb. I really didn’t want one of my wholesalers to be a killer. I was just getting that side of the business started.

He shrugged. “Who knows what it was about this time?”

This time? I glanced at the line behind us. It stretched to the street.

Charlene squeezed his hand. “You’re a good man. You’ll get through this.”

A cast-iron weight settled in my chest. How do you get through your wife being smashed by an oversized pumpkin?

“At least Chief Shaw is taking over the investigation,” Elon said. “It will get the attention it deserves.”

Charlene’s mouth puckered.

“I’m sure he will,” I said.

“Whatever you do,” he continued, “don’t go back.”

I looked at him blankly.

“When you’re in the haunted house,” he explained. “Keep moving forward, and you won’t get lost or ruin it for others.”

“Oh,” I said. “Right.”

We muttered more condolences and walked into the darkened barn.

“That poor man,” Takako said.

A sheet-covered ghost popped from behind a tombstone, and I jumped.

Charlene chuckled. “He got you good.” The whir of her racer was lost in the shrieks ahead of us.

Takako slid her hands into her pumpkin festival jacket pockets. “I read about his wife’s death in the paper this morning.”

“Oh?” I asked.

We moved into a mad scientist’s laboratory.

I scanned the tables for places someone could hide. A motionless Frankenstein’s monster lay upon an angled operating table. “What did the article say?” I asked.

The racer circled a long table with beakers bubbling on it. Someone squawked behind the table.

A zombie hopped up. “What the—?”

“Just testing,” Charlene said to the zombie. “Sorry, Takako, you were saying?”

“The article wasn’t very illuminating,” Takako said. “It said the body was found beneath one of the giant pumpkins, and that her death is being considered suspicious.”

No kidding.

We twisted and turned through the rooms-a haunted fairground, a haunted asylum, a classic haunted mansion. Through some trick, the barn seemed bigger on the inside than on the outside.

Takako, Charlene, and the pumpkin fell behind, and I found myself alone on a haunted pirate ship.

I waited for them beside a ship’s wheel, draped with fake spiderwebs. Charlene had been right to drag me from Pie Town. I would have hated to miss this. Of course, if I hadn’t come, I’d never have known—

Something creaked behind the mast.

I whirled, expecting a demented pirate.

The ship’s deck was empty.

Feminine screams echoed from the room next door.

I backed up, bumping into the ship’s wheel, and jumped again.

Brilliant. Scares were a feature of haunted houses, not a bug. I exhaled a shaky breath. And where were Charlene and Takako?

There was a faint popping sound. In the dim room, I turned, orienting on the noise.

A tennis ball bounced across the wooden floor. It slowed, rolling to a stop in front of my sneakers.

Oh, that wasn’t creeptastic. Not one bit.

“Charlene?” I called. “Takako?” Enough of this. I’d just go back and find them. I moved toward the entrance to the pirate room.

A sheet-clad ghost leapt from behind a pyramid of grog barrels. The spirit brandished a two-by-four. Nails sprouted from its business end.

“Okay, okay.” I backed toward the exit. Sheesh. The church took the keep-moving-forward rule seriously. “I get the point. Heh, heh. Point. Nails. Get it?”

The ghost wafted closer and raised the board, menacing.

My muscles tensed. “I’m going.” I turned and hurried forward. Stupid haunted house. Stupid rules. And what did ghosts have to do with pirates?

The skin between my shoulder blades heated. Sensing movement behind me, I pivoted.

A blur of white. The ghost leapt, board swinging.