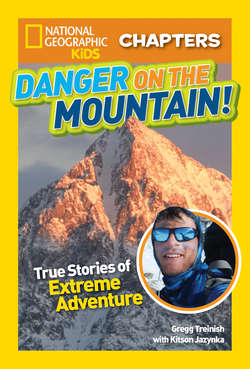

Читать книгу National Geographic Kids Chapters: Danger on the Mountain: True Stories of Extreme Adventures! - Kitson Jazynka - Страница 7

ОглавлениеThe pristine wilderness awaited Gregg in Garibaldi Park, north of Vancouver. (Photo Credit p1.2.1)

I could hardly hear anything except my own heavy breathing as I struggled up the steep ridge trail. My pulse throbbed in my ears. To make it to the top, I focused on a single tree up ahead. Ten more steps to reach it. Then I’d pick another towering pine tree and make a goal to reach that.

I was 16 now. Dealing with other kids at school had gotten harder for me. I tried to stay out of trouble, but it never seemed to work. I didn’t want to follow the rules. I pushed boundaries with my parents and my teachers.

My grandma Mandu seemed to sense that an outdoor adventure might help me. She offered to send me on a guided, three-week summer wilderness trek on the coast of British Columbia, Canada. I couldn’t wait to go. But once I was there, I was having a tough time. It was hard.

The rocky trail stretched out long and steep in front of us. We were in Garibaldi Park, a pristine wilderness north of Vancouver, Canada. I tried not to think about the weight of the pack on my back. Hardly anyone talked as our group slowly trudged up the hill.

The kid in front of me was slow. He kept stumbling and crying and holding up the group. We could only go as fast as our slowest member. I was getting upset with him.

Did You Know?

Garibaldi Park is home to mountain goats, grizzly bears, bald eagles, and endangered trumpeter swans.

Then he fell. Our guide, Guybe (sounds like GUY-bee) was quick to help. Guybe asked us to divide up the stuff in the kid’s pack and help him carry it. It had never occurred to me to offer to help. But I realized that was the quickest way to get to the top. I knew I was strong enough to carry a little more.

Guybe unzipped the kid’s pack. I reached in and grabbed a five-pound (2.3-kg) bag of apples and put it in my own pack. I carried it the rest of the day. Helping was a new thing for me. I was part of a team. I was doing something right. For once, I was not in trouble. That was a big deal.

I admired Guybe. He seemed fearless. He also had a lot of wilderness experience. Guybe had been a thru-hiker on the Appalachian (sounds like ap-uh-LAY-chun) Trail. That means he had walked the whole 2,190 miles (3,524 km) from Georgia to Maine, U.S.A.

Guybe and I talked a lot about long hikes. He told me he thought I could do a hike like the Appalachian Trail. I wasn’t so sure. Maybe I could do the Buckeye Trail. That’s the long-distance trail that loops around my home state of Ohio. That might be something I could do. But I wasn’t so sure I could do anything quite like Guybe did. To me, he was a mythical creature.

(Photo Credit p1.2.2)

Once during that three-week summer trek, he helped our whole group get through a scary situation. The trail had washed out after a storm. Thinking there was no way to get across, we stopped short. To our left was a wall of dirt and rocks that spilled across where the trail had been. To the right, the earth dropped off. I didn’t see how we could get around it.

Guybe skipped across the loose, wet rocks in his sandals. Then he looked back and told us “c’mon,” like it was nothing.

(Photo Credit p1.2.3)

A friend of mine refers to hiking as “land snorkeling.” You can see a lot when you’re on foot. When you walk through the woods—as opposed to driving or being on a bike—you notice everything. You see animals moving through the shadows. You see the bark on the trees. I always tell people to “hike their own hike.” Go where you want to go. Stop when you want to stop. And take your time as you land snorkel through the woods.

A couple of kids made it across the 10-foot (3-m) gash in the trail. But when it was my turn, I looked over the edge to the right. Roots dangled out from the side of the hill. Sharp rocks were piled a long way down below. My heart pounded. My feet wouldn’t move.

Guybe looked at me. “You can do it,” he said, “just go fast.”

I took a deep breath and launched. I went fast. The rocks skittered under my feet. I slipped and stumbled and went down on one knee. I heard the smash of a rock as it sailed over the edge and landed against another rock down below. I couldn’t believe I wasn’t dead yet.

Guybe had a way of making me believe in myself. I focused on his calm voice. I got up. I kept going. It all happened kind of fast. Suddenly, I was on the other side. I was terrified! But I was also laughing and talking with the other kids about the crossing. It was like pushing a boundary in a different kind of way. I had pushed myself.

Another time on that trip, we paddled sea kayaks around an unpopulated island off the coast of Vancouver. When a summer storm rolled in, I felt like I was paddling through a cloud. There was so much rain and mist that I couldn’t see a thing. I was cold and wet and had no idea where I was going. But I had trust in my guide, and I was gaining trust in myself.

Did You Know?

Early Arctic nomads hunted in hand-carved sea kayaks.

(Photo Credit p1.2.4)

After our group paddled to shore, climbed out onto the beach, and secured our stuff, Guybe taught us how to build a sauna on the beach. It was a fun way to get warm. We dragged branches and logs in from the woods. We set them up and built a teepee with a tarp. Then we built a fire inside it and put rocks on the fire. When the rocks got hot, we poured salt water on them. Warm steam filled our makeshift teepee. I breathed in the warm, salty air, feeling tired but strong and resourceful.