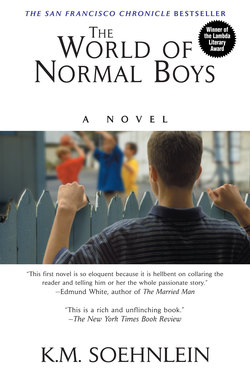

Читать книгу The World of Normal Boys - K.M. Soehnlein - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

EXPECTATIONS. REALITY.

Mr. Cortez writes each word on the blackboard, then draws a vertical line separating them. “What kind of things have people told you about high school? These are your expectations. What did you find when you got here? That’s reality.” This is group guidance, the last class of Robin’s first day of school, a class provided just for freshmen: “a rap session” was how Cortez, his guidance counselor, had described it when Robin met him last spring for orientation. Cortez is a young Puerto Rican guy with a mustache and curly hair. He wears Frye boots and tells the students, “Expectations and reality don’t always match up. That can be a really bad trip. That’s why we try to keep the lines of communication open and not get hung up.”

Robin’s own gloomy expectations for the day have largely been met. Every class begins the same: nervously waiting for seats to be assigned. He longs to sit in the back, or along the windows—somewhere inconspicuous—but the tyranny of alphabetical order always leaves him smack dab in the middle, an “M” surrounded on all sides, third row across, third row back, like some obnoxious center square on Hollywood Squares—like Paul Lynde, except he wasn’t even as funny as Paul Lynde. (He remembers a question from the show: “Betty Ford said it was her second greatest pleasure in life. What was it?” Paul Lynde: “Sucking on a rum cake.”)

All the guys in his classes have longer hair than they did last year. They look like teenagers now—taller, wider necks, deeper voices. There are three acceptable ways to dress: sports team logos (for the jocks), concert T-shirts (the scums), and plaid shirts with snaps instead of buttons (the brains). Robin’s in a polyester patterned thing, brown and gold and white, and snug fitting, chocolate brown dress pants that he really likes—though after looking around at what everyone else is wearing, he starts to think he might like them too much.

Humiliations great and small greet him every class period. In English, the guy in the seat in front of him, Jay Lunger, announced, “Your name is gonna be Ears.” Jay was bigger than him by a couple of inches and had no problem saying whatever he wanted. When Robin tried to laugh off the insult, Jay said, “It’s not that funny. You’re walking around like you got half a plate on each side-a your head.” For the following forty-five minutes Robin examined every pair of ears in the room: how far they stuck out, how long they were, if the lobes were attached or not. Between periods he checked himself out in the bathroom mirror, turning his head from side to side. His ears weren’t that big, he reasoned, they just curved out at the top, like fins on a classic car. He decided he’d have to grow his hair longer anyway, just in case he was wrong.

In phys. ed. they played kickball, and when he was up, he swung his foot and missed the ball entirely. “Never heard of anyone getting a strike in kickball,” Billy Danniman, standing on deck, sneered. In algebra, he wound up in the seat behind Diane Jernigan, who gloated to him about how psyched she was that she and Victoria had so many classes together, while he seethed with envy: Diane Jernigan, that bitch, last year she got a whole bunch of girls to gang up on me because I said I hated Kiss. At lunch, he took his place at a table with a kid from his neighborhood named Gerald and Gerald’s friends, who passed the hour talking about an upcoming Star Trek convention they were all really stoked about. He spent most of the period surveilling the cafeteria for someone else to sit with tomorrow; there was his lab partner from science, George Lincoln, but George was black, and the black kids all sat together at three tables on the far end of the cafeteria.

The one class he was looking forward to was art—he’d been told that freshmen learn how to develop film and print photographs, which he’s always wanted to do. There was no mention of this, however, from Miss Blasio, who used up the class drilling them on which solvents counteract which kinds of paint. Miss Blasio was six feet tall, with brown hair halfway down her back and long, red-painted fingernails. Robin became mesmerized by the way she regularly let a thick ribbon of hair fall in front of one shoulder, then, with a purposeful toss of her head and the back of her hand, flipped it behind her again. It was hypnotic—hair sliding around the left shoulder, then flip; then around the right shoulder, flip. He timed it—one flip about every four minutes. Every ten minutes or so she gathered the whole mop of it in the back, made a ponytail in her fists, and then let go. Whoosh. Next to Miss Blasio’s name in his notebook he wrote “a.k.a. Cher.”

Already group guidance is an improvement on the day. The chairs are in a circle, and Cortez has instructed them to sit anywhere they want while they rap about expectations versus reality:

“School sucks.”

“I hate it when people make fun of me for liking school.”

“I’m sick of all these uptight teachers telling me what to do.”

“I’m a Christian, and I find it very hard to feel comfortable because kids act like that’s not cool.”

Cortez writes, “Expectation: We’re all in this together. Reality: Conflicting values.”

Robin gets the nerve up to raise his hand. “I was told that we’d be doing photography, you know, in art, but she didn’t even mention it.”

Cortez nods. “We can check into that. Who’s your teacher?”

“Miss Blasio,” he says, then rolls his eyes and adds, “Cher.”

A few big laughs from around the circle. His face turns red—embarrassed, until the satisfaction of having told a successful joke settles in. He even dares an imitation of Miss Blasio’s hair toss—flip, flip—which grabs a few more approving chuckles from his classmates. Cortez himself breaks into a wide grin, though some sense of propriety prevents him from actually laughing at a teacher’s expense.

Robin remembers his list of Chances: one of them was to tell jokes in class. This is the first victory of his high school life. For a few hours, it erases all of the day’s defeats.

A well-placed sarcastic comment, out of earshot of his teachers but loud enough for those in the desks around him to hear, becomes Robin’s sole release—the one chance he successfully takes again and again, until it isn’t chancy at all, until it is one of the few times that he doesn’t shrink from the sound of his own voice. Mornings are gloomier since Victoria’s proclaimed that she is no longer accepting rides to school from her brother—“I’m not gonna sit around and wait for him to get busted for drugs,” she announces to Robin—thereby effectively cutting off Robin’s access to Todd. Most days, he gets home from school and for no reason he can articulate is so lethargic and exhausted that all he can do is collapse in front of the TV. He disappears into the heated storylines of General Hospital and The Edge of Night until his mother gets home from her part-time job at the Greenlawn Public Library. Fatigue takes root in his joints—from his knees to his jaw, as if he’s been holding himself stiff for hours. When his mother asks him how the day went, he scavenges for something he can tell her, something she would appreciate. He doesn’t tell her Billy Danniman called him a fag in gym class after he dropped a fly ball; she would only urge him not to dwell on it. He leaves out the disappointment of yet another awkward, on-the-fly conversation with Victoria—the only kind of interaction they seem to have anymore; his mother would simply remind him that his future is far away from Greenlawn and that adolescent friendships are never the important ones in life. He certainly doesn’t tell her when the best thing that happened all day was Todd sending a halfhearted “Yo” his way as they passed in the hall (leading to a kind of hopeful reverie on Robin’s part that yes, in fact, he and Todd might actually hang out sometime). So instead he tells her what he’s reading in English because this delights her most of all. Dorothy rereads for herself whatever he’s been assigned so that they can talk in detail about the story. Books—stories—are what his mother appreciates above all else.

One day toward the end of September, Dorothy lets Robin miss school. He’s been waiting for this: their City Day, one of the days every few months when they disappear from Greenlawn together. They’ve been doing this for years, dressing up in their most stylish clothes and traveling by bus through New Jersey towns that bleed together unremarkably, onto the Turnpike, where the first views of the New York skyline are revealed, and into the eerie glow of the Lincoln Tunnel. They hurry through the crowds at the Port Authority Bus Terminal into one of the Checker Cabs that line Eighth Avenue like chariots for visiting royalty.

Robin gives instructions to the cab driver—“Take us to the Museum of Modern Art, on 53rd Street between Fifth Avenue and Avenue of the Americas”—and Dorothy tips generously, her bracelets jangling as she pulls bills from her purse. She is most animated on these days, an enthusiastic tour guide, telling Robin about her adventures in the city in the early ’60s, when she graduated from Smith College and found work as a secretary at a publishing company. She tells him about the well-dressed crowds strolling Times Square at 2 A.M., about drunken authors at book parties, about the handsome men who courted her over coffee at the Automat. She shows him the apartment on West Twenty-Third Street where she and Clark first lived after they were married, where Robin spent the first four years of his life. She tells him things on these trips that he never hears her telling anyone else—punctuating the details with dramatic exhalations from her Pall Malls—which leaves him feeling uncommon, a coconspirator, the keeper of secret myths.

And her stories change: today she mentions a surprise appearance by Miles Davis at the Five Spot in 1963; the last time she told this story it was Sonny Rollins in 1962. Robin used to correct her, but Dorothy only laughed off the inconsistencies. Now he has come to welcome the way her stories shift; it is the excitement of them, and not the facts, that he values. She encourages him to make up stories of his own. A woman in sunglasses and a fur coat hurries past the park bench in Washington Square where they are sipping coffee. “Who is she,” Dorothy asks, “and what is she up to?”

Robin takes a moment to think, and a tale tumbles forth: she is a jet-setting fashion model who dances all night at Studio 54, but deep down she’s miserable, she’s spent all her money on champagne and caviar and cocaine; now she’s broke, all she has left is that fur coat, and she’ll be trading that in at the Ritz Thrift Shop any day now. It feels like ESP when he does this, but instead of reading someone else’s mind, he’s tuning in to transmissions from some alien part of his own, where ideas are always buzzing, where static can be translated into stories.

The tragedy of the City Day is always the aftermath, when he sits across from Ruby at the dinner table and absorbs her jealousy at having been left behind, or argues with Jackson about why a symphony at Lincoln Center is more interesting, more relevant, than a playoff game at Yankee Stadium. Even his mother loses her sheen in the days that follow, as she returns to shopping at the A&P and telling his father to remove his feet from the coffee table and correcting Robin’s language whenever, God help him, he slips into slang like some common New Jersey teenager.

A Sunday night at the beginning of October: Clark is dragging Dorothy to a World Series party with Uncle Stan and Aunt Corinne. As Robin watches his mother glide down the stairs wearing a new pantsuit that he helped her accessorize—rhinestone post-earrings, a Diane von Furstenburg scarf, a bronze leather bag and matching shoes—it becomes clear how unpleasant this night will be for her. Stan berates her for keeping them waiting, and Clark fumbles to apologize on her behalf. Even Corinne has shown up in a Yankee cap, spirited and enthusiastic for the big game. Robin admires his mother for not displaying false excitement, for letting her style set her apart; still he can’t help notice in her departure a dread that they share. This party is like a grown-up version of gym class.

His cousin Larry has been deposited at their house, placed with Ruby and Jackson under Robin’s care, though Robin quickly retreats to his room with the paperback copy of East of Eden he’s been assigned for English class. His mother once took him to see the movie at the Thalia in New York, and now every page is charged with the electric image of James Dean. Robin lies facedown on the bed, skipping ahead until he gets to Cal’s scenes; he hears James Dean speaking for Cal, murmuring his pain and rebellion. It gives him a boner, which he grinds distractedly into the sheets as he reads.

An hour later, when a sharp, burning stink wafts under his door, he heads downstairs to investigate, carrying the book in front of his fly to hide the evidence.

The living room is hazy with smoke; the game is on TV but no one is watching it. In the kitchen, Jackson stands on a chair in his underwear, trying to push open the skylight over the sink. Larry, in his underwear, too, is clutching his ribs and faking an uncontrollable coughing fit.

“What the hell?” Robin demands.

“We torched the Rice Krispie Treats,” Jackson says.

“You’re supposed to put them in the fridge,” Robin admonishes, “not the oven.”

“Shut up, Susie Homemaker,” Larry snorts. Jackson begins laughing and loses his balance in the chair. Larry gives him an extra shove, which knocks him into the sink; his elbow hits the faucet and the water pours out onto his belly. When he stands up his underwear is soaked.

“Ah-ha,” Larry says. “Couldn’t hold it in.”

There are few people Robin dislikes more than his cousin. Even though Larry’s a year younger, he always manages to intimidate Robin. Larry has a Bowery Boy’s face: eyes forever moving into a squint, nose scrunched up as if he’s been forced to do something he hates, mouth in a sneer. Proud of his farts, quick with his insults, endlessly pulling pranks—of all the put-downs Robin’s learned from his mother, the one that suits Larry best is primitive. Worst of all is his influence on Jackson. Most of the time Robin thinks of Jackson as simply the pest in the next bed, the loudmouth never out of earshot, a nuisance no worse or better than bad weather. But Larry drags Jackson behind closed doors, and after much giggling and half-whispered plotting they emerge with a new campaign of terror laid out. They bellow dirty jokes they don’t necessarily understand and laugh too loudly at them. They taunt Robin. Put Jackson alongside Larry and it’s as though the monster has grown a second head.

“Don’t expect me to clean this mess up,” Robin says, and leaves the kitchen, opening a window to air out the room.

Ten minutes later, Robin is roused from his reading again, this time by Ruby’s squeals. He runs to the hall and sees Jackson and Larry darting out of her bedroom naked. “Streakers!” Ruby shrieks in horror.

Robin freezes for a moment—stunned at the flash of skin—and then, feeling that it is his duty as the oldest one to impose some order, calls out, “You guys, cut it out.”

Larry and Jackson stop at the top of the stairs. Side by side, hands in the air, they shake from the hips. “Freddy and Petey on parade!” Larry yells.

Robin looks at their dicks slapping to and fro. Jackson’s is just a little boy’s pud, no bigger than his pinky, but Larry’s is already developing, taking on a fullness that looks like his own. Larry pinches two of his fingers around it and gives it a shake. “Squirt, squirt,” he says mockingly, staring Robin in the eyes, his gaze a dare, not just defiant but belittling. Robin turns his eyes away from them, red faced, and yells, “I said cut it out.”

“Oh, we’re scared.” Larry smirks and then takes off downstairs after Jackson.

Robin charges after them, unsure what else to do. His confusion escalates as they race through the living room, the dining room, the kitchen—their bared flesh in this setting is doubly disturbing. Larry’s daring makes Robin feel timid; the way he just flaunted himself in front of Robin feels like a personal insult, a knowing “gotcha” for which Robin must now retaliate.

Jackson disappears through the basement door. Larry turns around and spits out, “No girls allowed,” slamming the door behind him.

The aftermath of the Rice Krispie Treats is strewn across the countertop. Robin grabs the metal mixing bowl, smeared with sugary goo, the spoon, the box of cereal, and the charred baking pan. He throws open the door. At the bottom of the dark stairway, he can make out two crouched figures. Before they have a chance to move from their hiding place he hurls everything at them. A surprised yelp rises up from Jackson. Larry just laughs like a gleeful gnome. Robin storms away, frustrated that he missed his main target.

Every door has its own particular voice. The chunk-chunk of the car being exited in the driveway, the squawk of the screen door arcing wide, the metallic turn of the front door’s loose knob, the sweep its lower edge makes on the hall carpet. From his bed Robin follows the path of his parents’ return, hears their muffled speech, the heaving pad of their feet on the rug. Something’s not quite right: he can hear Aunt Corinne with them, moving toward the basement (the airy fling of that door familiar, too). She’s calling for Larry. Robin gets up and goes to the top of the stairs.

“Mom?”

His mother lies wilted over his father’s shoulder. He’s trying to maneuver her up the stairs. Behind them Corinne is placing Dorothy’s purse on an end table and motioning for Larry, who’s standing in his shorts and T-shirt. “What’s the big idea?” he asks sleepily, but Corinne shushes him.

“Will you be OK, Clark?” she asks.

“Yeah, that’s me, the OK Kid,” his father says flatly.

Corinne pauses before moving. “I’m sure Stan didn’t mean anything. I think Dottie just took it wrong.”

“ ’Course,” Clark says, not meeting her eyes.

Robin feels himself tensing up. Uncle Stan insulted his mother? She got drunk because of it? “What did he say?” he blurts out.

“Never mind,” Clark says. “Give me a hand here.”

“Why do I gotta go?” Larry complains, but Corinne just pushes him out the door.

Robin steps to his parents. “Your mother outdid herself tonight,” Clark says. Dorothy’s sagging face seems to have been loosened from its bones. Robin wipes a thread of spittle from her chin. “Let’s get her upstairs,” Clark says. “She’s gonna give me a dislocated shoulder.”

Clark swings Dorothy upward, and Robin hooks himself under her free arm. He drags the weight behind him, one step at a time. “What happened?” he asks again, a growing sense of outrage and fear knotting in his belly. Did it have something to do with her outfit? Did his mother feel overdressed and out of place? Is it his fault for encouraging her to dress as she would on one of their City Days?

Clark guides them to the bathroom. “She’s going to need another stop at the trough.” They position her on the floor in front of the toilet. In the sudden bright light, the bathroom’s grime rises to prominence. The toilet rim where Clark places Dorothy’s hands is marked by pale yellow splashes and a couple of stuck pubic hairs. Robin runs a cloth under cold water and presses it to his mother’s face.

She stirs at the contact, sliding forward and bonking her skull on the upturned seat. “Oh, it’s you,” she slurs.

The sloppiness of her speech fills him with pity. “Hi, Mom.” He wipes the cloth across her forehead tenderly.

“Come on, Dottie,” Clark says, “Let’s take care of business and get you to bed.” Robin can smell alcohol on his father’s breath, too, though he shows no signs of losing his composure.

Dorothy remains motionless. A sweet noise hums from the back of her throat, the gurgle of an infant. “This is taking too long,” Clark says. He reaches around and pries Dorothy’s mouth wide. Robin watches in horror as one of Clark’s fingers disappears inside.

“You’re hurting her,” he protests, as his mother gags, the tendons in her neck tightening.

“I’ve done this before,” Clark whispers solemnly. He wiggles his finger and then pulls it out just in time to release a funnel of clear vomit.

Jackson is suddenly there in the doorway, wide-eyed. “Holy barf bag!” he exclaims. Robin spins around and glares at him.

Clark speaks without looking at him, “Why don’t you go back to sleep, kiddo?”

Dorothy heaves again and sends out another splash. “Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Puke-o-rama,” Jackson announces.

“Dad, could you tell Howard Cosell his services are not needed?” Robin says.

“Where’d Larry go?” Jackson asks.

Robin says, “We put him out with the trash.”

Clark slaps his hand on his thigh. “Can you guys just put the sibling rivalry on hold? Jackson, go to your room. Robin, wipe Mom’s face again.”

“Oh sure, Robin gets to have all the fun,” Jackson says before splitting.

“We’re gonna lift you now, Mom, OK?” Robin says softly into her ear, but she does not respond.

“She’s out again,” Clark says. Robin can hear the disgust in his father’s voice. He feels it, too, but not for her. His mother this far out of control—this just can’t be her fault. Someone else is to blame.

“I saw Mom do the Technicolor yawn.” Jackson’s voice is an excited whisper in the dark. Robin stares up from his bed to a crack in the ceiling.

“Don’t talk about your own mother that way,” Robin says.

“Oh, give me a break. That was a pisser.”

“I’m sick and tired of your attitude.”

Jackson breaks out into laughter. “Why do you do that?”

“What?”

“Talk like Mom. I’m sick and tired of your attitude.”

The words sting. Robin rolls on his side, faces the wall. “You don’t understand anything the way I do.”

“All I know is nobody wants some kid their own age talking like their dumb mother. Why do you think Larry’s always bothering you? You ask for it, Robin.”

Robin feels his eyes watering. Maybe Jackson’s right. Maybe he does provoke the trouble that finds him. But how could he explain to Jackson the look that Larry gave him when he wagged his dick at Robin, the way he knew Robin was staring at his dick, the way he turned it against him? How can he explain himself to Jackson when they don’t even seem to speak the same language?

He finally speaks of the only thing he understands: his idea of the far-off future. “I’m going to move to the city one day and live in a penthouse, and all of this will be some funny thing in the past if I even remember that much of it.”

“Yeah, right. You and Mom can move off together and talk to each other like a couple of old ladies and drink until you puke.” Suddenly he throws back the covers. “I gotta take Petey for a pee.”

“You have a name for your dick?”

“Yeah, me and Larry. His is Freddy.”

“That’s disgusting.”

“No, it’s not. It’s funny. What’s your problem?”

He shuts his eyes so tight that neon bleeds into the blackness. He doesn’t understand how this works. Larry and Jackson get naked and name their dicks, but when Larry sees him staring at “Freddy,” it’s a bad thing. He says a little prayer. God, give me a new life. This one isn’t working for me. He waits for a merciful bolt of lightning to strike his brain, to offer him some clue as to how it all works, this whole world of normal boys.