Читать книгу The Last Leonardo: The Making of a Masterpiece - - Страница 9

CHAPTER 1 Flight to London

ОглавлениеRobert Simon had plenty of legroom on his flight to London in May 2008. He was flying first class, an unusual luxury for this comfortably successful but unostentatious Old Masters dealer, president of the invitation-only American Private Art Dealers Association. During moments of transatlantic turbulence he cast a glance down the aisle at one of the first class cabin’s cupboards, where he had been given permission to stow a slim but oversized case.

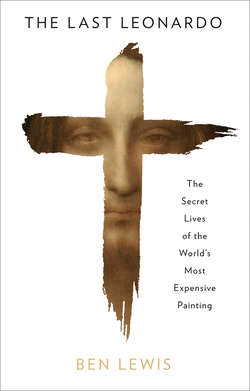

It contained a Renaissance painting, 66cm high and 45cm across, of a ‘half-figure’, to use the old-fashioned art historical term, of Christ. The portrait composition showed the face, chest and arms, with one hand raised in blessing and the other holding a transparent orb. One reason Simon was worried about the painting was because he had not been able to afford the insurance premium he had been quoted for it. He had bought it three years earlier for around $10,000 – or so he had told the media – but it was now thought to be worth between one and two hundred million dollars.

Far from being the life of luxury many people imagine, dealing in art can be a precarious existence even at the highest levels, because selling expensive paintings is, well, very expensive. Top-end galleries have vertiginous overheads. Walls have to be repainted for each show, catalogues printed, wealthy collectors wined and dined. Simon had spent tens of thousands of dollars restoring the boxed painting, and had not yet seen a penny return.

Solidly built, medium height, Jewish, fifty-something, soft-spoken, polite, Robert Simon is the kind of person who believes that modesty and understatement are rewarded by the higher forces which direct our lives. He projects a modest, pleasant, but slightly brittle calm. ‘Loose lips sink ships,’ he likes to say, repurposing a slogan emblazoned on American propaganda posters in the Second World War to the business of art.

Simon leant backwards in his seat. He was overcome by that mood men fall into when they know the die has been cast, the pieces arranged on the board, and there is nothing more they can do except perform a sequence of now predetermined actions. There could be no more organising, influencing, persuading. It was all done, to the best of his abilities. The confinement of the long pod of the aircraft cabin and the sensation of forward motion provided by the thrust of four jet engines combined into a physical metaphor for this moment in his life.

Alongside the submarine, the parachute and the machine gun, the aeroplane was the most famous invention anticipated by the artist who had consumed Simon’s life for the previous five years. Leonardo da Vinci was not the first human who had designed flying machines, and it is likely he never built one himself, but he had studied the subject for longer, written more, and drawn designs of greater sophistication than anyone before him. His ideas for human flight were based on years of watching and analysing the airborne movements of birds, bats and flying insects, and recording his observations in notes and drawings. As Simon felt air currents lifting up the plane, he recalled how Leonardo was the first to recognise that the movement of air was as important to a bird’s flight as the movement of its wings.

On 15 April 1505 Leonardo completed a draft treatise On the Flight of Birds, also known as the Turin Codex. It was only about forty pages long, filled with unusually neat lines of text, written in black ink in his trademark mirrored handwriting, right to left, interspersed with geometric diagrams, and the margins sometimes decorated with tiny, beautiful sketches of birds in flight. Leonardo’s early ornithopters, or ‘birdcraft’, had wings shaped like a bat’s, because, as he wrote, a bat’s wing has ‘a permeable membrane’ and could be more lightly constructed than ‘the wings of feathered birds’, which had to be ‘more powerful in bone and tendon’. Leonardo positioned his pilot horizontally in a frame underneath the two wings, where he was to use his arms and legs to push a system of rods and levers to make them flap. Historians say Leonardo soon came to realise that the human body was too heavy, and its muscles too weak, to provide enough power for flight, so his later designs had fixed wings and were more like gliders. He imagined launching one, appropriately, from a mountain ‘named after a great bird’, referring to Monte Ceceri, or ‘Mount Swan’, in Tuscany. Relishing the avian metaphors, Leonardo wrote that his ‘great bird will take its first flight on the back of the great swan, filling the universe with amazement, filling all writings with its renown and bringing glory to the nest in which it was born’. Nothing he designed ever flew. The contraptions were almost daft, but there was prophetic genius in his perception of the natural phenomena and laws of nature which gave rise to his machines.

Robert Simon knew that, whatever the outcome of this trip – and that really could be everything or nothing – it marked the pinnacle of his career to date in the art world. If everything went well, he would probably earn a place in the art history books. If not, he would remain respected but unexceptional. This flight also represented the apogee of something more personal. In common with most art dealers, there was a motivation behind his career which had nothing to do with money or success, and which had shaped his life for somewhat longer: an unconditional, unrelenting love for art; not modern and contemporary art with its splodges, squiggles and splats, but the great art of the past, especially the Renaissance, in which the eternal stories of the Bible and of Ancient Greece and Rome were brought to life by the melodramatic gestures of bearded men and golden-haired women, amidst thick gleaming crumples of silk and satin cloth, set against a classical backdrop of esplanades and porticos, temples and fortresses.

When he was fifteen, Simon went on a school trip to Italy. He remembers the winding roads of the hills around Florence, the low sun flashing through the cypress trees as the bus drove towards the town of Vinci, the birthplace of Leonardo da Vinci, from Vinci. (By coincidence, my parents would take me on a similar trip in my own teenage years.) ‘Leonardo has been my deity for most of my life – and I am not alone,’ Simon told me. ‘He’s my idea of the greatest person that civilisation has produced.’ Over the decades Simon had seen every major Leonardo exhibition that had been staged, and every Leonardo painting, and ‘as many drawings as I could’. His professional life, which now revolved around Leonardo, had taken him once before into the artist’s sphere, in 1993, when he was asked to examine the Leicester Codex, one of Leonardo’s revered manuscripts, for its owners. It is now owned by Bill Gates, but then belonged to the oil magnate Armand Hammer’s foundation.

Simon’s family were well-to-do but had not been deeply involved in art. His father was a salesman of eyeglasses. Simon was sent to an exclusive, academically orientated high school, Horace Mann School, in the New York suburb of Riverdale. Afterwards he specialised in medieval and Renaissance studies, and then art history, at Columbia University. He wrote his PhD on a newly discovered painting by the sixteenth-century Italian Mannerist painter Agnolo Bronzino, held in a private collection. A portrait of the Florentine Medici ruler Cosimo I in gleaming armour, it was known from the many copies, around twenty-five of them, which hung in museums and homes, or sat in storerooms around the world. Art historians had long considered that the original work was the one in the Uffizi, Florence’s famous museum. However, in a story with uncanny parallels to that of the painting that he was now taking to London, the young Simon had argued that he had identified an earlier original of this painting, the owners of which wished to remain anonymous. He published an article about it in the esteemed journal of connoisseurship and painting, the Burlington Magazine.1 The painting now hangs in an Australian museum, as a Bronzino, although some experts still believe it was painted by the artist’s assistants.

Simon climbed the ladder of the art business slowly. He was a research fellow at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. He taught briefly. He tried, but never succeeded, to enter the academic side of the art world. ‘The basic truth is I could not find an academic position in a place I liked,’ he says.

He contributed reviews and articles to the Burlington Magazine, wrote catalogue essays about Italian Renaissance artists for Sotheby’s and minor museum exhibitions from Kansas to Milan. In the 1990s he also wrote catalogues for selling exhibitions at New York’s Berry-Hill Galleries, which collapsed under multiple lawsuits in the mid-2000s.

Simon found employment as an appraiser, one of the more discreet jobs in the Old Masters art market. The appraiser is invited by a collector to assess the quality and value of a work of art, usually with an eye to a sale or purchase, also for divorce settlements and for gifting or loaning to museums, for which there are lucrative tax breaks which American collectors wisely take advantage of. Just as often, the appraiser answers a call from a family that has inherited artworks. ‘Often one is called in to value the estate of someone who has recently passed away, so it’s not exactly a pleasant situation. Maybe two months after a person’s died, you’re in an apartment and the place has not been touched and there are paintings still on the wall, often things that have been there for years and haven’t been cleaned. You’re looking at these paintings in poor light and poor conditions, and there’s a certain treasure-hunting feel to it, but it’s also compromised by the situation.’ Years of experience had taught Simon to peer through the gloom of dark rooms, and the dirt of unrestored and unloved paintings, to perceive a glimmer of quality and art history.

Appraising is a job that embodies one of the great conundrums of the art world – the source of much suspicion and conspiracy theory – which is the interwovenness of scholarship and the market. As Simon says of his work as an appraiser, ‘It’s usually about the financial component, but often enough one has to do a fair amount of research to figure out what it is exactly that one is dealing with before one gets to the value stage.’ The appraiser needs to be as familiar with the development of an artist’s style as he or she is with archives of auctions and inventories, through which a painting’s history may be traced. And the appraiser needs to understand the parabolas of the rise or fall of an artist’s prices, as collated in subscription-only databases. This work, and indeed every kind of dealing in Old Masters, requires a capacious visual and factual memory. You need to be able to recall thousands of works of art, often in their smallest details.

Robert Simon began working as a dealer in 1986, and set up his own gallery in the house he bought in Tuxedo Park, New York state, in the early 1990s. He specialised in European Renaissance and Baroque art, and also took an interest in colonial Latin American art. He followed up his discovery of the Bronzino portrait with a handful of other Renaissance finds: a Parmigianino here, a Pinturicchio there. Over the years he has sold a handful of paintings and sculptures to American museums in Los Angeles, Washington, Detroit, Yale and so on. Curators appeared to respond favourably to his low-key, insistently academic manner. But whatever his past successes, he is the first to admit that he had never sold a work of art as exceptional, or as expensive, as the one he had walked on board this aircraft with, carrying it in a custom-made aluminium and leather case supported by a long strap over his shoulder.

Inside the elegant case was a painting depicting Salvator Mundi, Christ as Saviour of the World, which Simon now believed to be by Leonardo da Vinci. He had only heard informally who would be looking at his picture in London. A few months earlier in New York he had shown it to the director of Britain’s National Gallery, Nicholas Penny. Penny was impressed, thought it could be a Leonardo, and had sent one of his curators, Luke Syson, across the Atlantic to examine it. Syson had begun work on an ambitious Leonardo exhibition that would open several years later, and he saw potential in the painting too. Simon’s trip to London was Penny and Syson’s idea. It would be highly irregular, if not unprecedented, to include a recently discovered but unconfirmed work by such a famous artist, and one which was also currently on the market, in an exhibition at a museum of the international standing of London’s National Gallery. Syson and Penny decided to discreetly convene a panel of the greatest Leonardo scholars in the world to judge the painting behind closed doors, before taking a decision on whether to include it in their exhibition.

Simon knew the odds would be stacked against him and his painting. There was a small army of Leonardists, as they were known, traversing the world, each with a long-lost and newly discovered Leonardo under their arm, trying to build an array of opinions favourable to their cause from museums and universities. Different art historians were allied to different paintings, and, such is the nature of academia today, all were competing with each other. There was the so-called Isleworth Mona Lisa, originally from a collection in a British country house but now owned by a consortium of investors who had set up a front organisation called the Mona Lisa Foundation. Western museums never showed it, but the Isleworth Mona Lisa had been exhibited in a luxury shopping centre in Shanghai. There was a Leonardo self-portrait, known as the Lucan Panel, discovered in southern Italy by an art historian who was also a member of a society linked to the Order of the Knights Templar, founded in the twelfth century, to which, legend has it, Leonardo himself had once belonged. That painting had been on show at a Czech castle, but was turned down by the University of Malta. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London had the Virgin with the Laughing Child, a small terracotta which it had long attributed to the Renaissance artist Rossellino, but which this or that art historian periodically tried to reclassify as Leonardo’s only known surviving sculpture. There was even another Salvator Mundi supposedly by Leonardo, known as the Ganay, named after its last known owner, the French resistance hero Jean Louis, Marquis de Ganay. The last time a painting’s reattribution to Leonardo had been widely accepted was ninety-nine years ago: the Benois Madonna, which today hangs in St Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum.

When Old Master dealers are not selling established masterpieces on behalf of an important client – the easy side of the business – they spend their time finding lost, overlooked or simply underrated works of art, dusting them off, identifying their author and then attempting to sell them as something bigger and better than what they had originally bought them as. The game is to exercise ‘connoisseurship’, using the eye, as it is known, to spot undervalued works. ‘I liken this ability to recognise an artist from what he paints to knowing your best friend’s voice when he calls on the phone,’ Simon told me. ‘He doesn’t need to be identified, you just know, from a combination of the intonation of the voice, the timbre of it, the pattern of speech, the language that he or she might use. There are these elements that when put together amount to fairly distinctive patterns that you, as someone who knows this person, would recognise. That’s really the essence of connoisseurship. There are many in the art community and the art historical community who dismiss it as some sort of voodoo process, but it’s both very rational and at the same time is based on a subjective understanding of things certain people have a knack for, or have studied …’ It is not easy to find the right words to define this elusive process. No wonder Simon was nervous.

It’s worth mentioning that the painting inside his case was a connoisseur’s worst nightmare. It had once been as damaged as any Renaissance painting could be. It had a great slash down the middle; the paint had been scraped away to the wood on parts of the most important part of any portrait, the face; it had broken into five pieces and was held together by a ramshackle combination of wooden batons on the back, known as a ‘cradle’. There was no contemporary documentation: not a contract, not an eyewitness account from the time, not a note in a margin about this painting, not one scintilla of evidence that dated from the lifetime of the artist, aside from the odd drawing of an arm or a torso, which bore only a partial resemblance to the finished picture. The painting had vanished from sight for a total of 184 of its estimated five hundred years of existence – 137 years between 1763 and 1900, and another forty-seven years between 1958 and 2005. When the great British art historian Ellis Waterhouse saw it at an auction in London in 1958, he scribbled one word in his catalogue: ‘wreck’.

Robert Simon was on a high-risk mission. He hadn’t even been able to afford the insurance premium for the full worth of his hand luggage. The auction house Sotheby’s had helped him in the end by kindly writing a low valuation of the painting at only $50 million. His piece was fragile. He wasn’t sure it would survive the plane trip, let alone make it onto the walls of a world-class museum or into the saleroom of a famous auction house. The panel on which the painting had been executed had been pieced back together and beautifully restored, but under its freshly varnished surface lay a hidden flaw: a huge knot in the lower centre. When it was studied by technical panel specialists in Florence, they said it was the worst piece of wood they had ever seen.