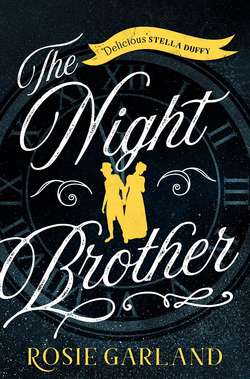

Читать книгу The Night Brother - - Страница 11

GNOME 1899

ОглавлениеEvery night it’s the same.

I come to, gasping, and I’m off that bed like it’s on fire. I squint at the mirror but won’t be convinced till I’ve run my hands the long and the short of what I see: head, fingers, knees and toes, ballocks and bumhole. It’s only then I can breathe easy. I’m in one piece, all twelve fine upstanding years of me.

It’s a crying shame to cover such a splendid specimen but I can’t go outdoors in my birthday suit and that’s a fact. Nor shall I wear out this night in self-admiration when there’s adventure to be had. The moon doth shine as bright as day, et cetera, and I have merriment to attend to. A lad of my mettle can perish of cloistering cling and playlessness.

I drag my britches from underneath the mattress where they’ve been pressed a treat and tuck my hair under my cap. With my shirt half-buttoned I’m raring to be gone, but there’s no point in doing so without a penny in my pocket. I tiptoe downstairs quieter than the mice worrying the walls and dig my hand into the sugar bowl on the mantel. If Mam will insist on stowing thruppences in such an obvious place it’s her funeral if half go missing.

I avoid the front door. The shunt and rattle of those bolts are enough to wake the dead and I’d get what for. Out of the bedroom window is my way, the best way. I creep back up without a squeak and pound the corner of the sash: three sharp punches and it slides up, wide enough to stick out my head. My left arm follows, then the right and to round it off I wriggle my hips clear. Watch a cat ooze under a door and you’ll know how it’s done.

I am free.

I swing off the ledge, ripping the seat of my trousers. I’ve no time to attend to such inconsequential matters. Mam will fix it. Down the fall-pipe, hit the ground and I run, savouring that first rush of delight, heady as a pint of best bitter downed in a single gulp.

I dance the tightrope of the pavement edge, dash between soot-faced terraces that squat low on their haunches. It matters not what I’m racing from or to; all I know is that I am alive. I am a mucker, a chancer, a chavvy, a cove. I grab life by the neck and squeeze every drop into my cup. If it’s good, I’ll take it by the barrel. If it’s bad I’ll do the same. I take it all: the world and his wife, the moon on a stick and the stars to sprinkle like salt on my potatoes. I hammer on doors for the thundering crash of it. Chuck stones at windows to hear the glass crack and the spluttering interrupted snores of those inside.

‘Wake up!’ I cry, windmilling my arms. ‘Life’s too short to spend it sleeping!’

I am the handspring of time between shut-eye and wake-up, the dream forgotten upon waking, the taste it leaves under the tongue. I am the crust of sleep in the eyes, the grit on the sheet. I am the yawning drag of Monday morning. You can keep the day with all its labour, misery and grime. I am King of the Night. I am Gnome.

I won’t be here forever. I have plans. Away from cramped windows, tiny doors, squeezed staircases; away from brick and cloud and rain-puddled gutters. I will go west. Not Liverpool, not Ireland – America. There’s a dream of a place: men in broad-brimmed hats and fancy moustaches so long they can wrap them around their thumbs; cornfields that stretch forever with not a fence to bar the way; cattle herds that take a day to rumble by. That’s where I’ll go. See if I don’t. It’s a greater journey than I can make in one night. But a man must have dreams.

All in good time. Tonight, Shudehill Market will suffice. It’s a fine place for a Saturday night’s entertainment, or any night for that matter. The crowd is as thick as mustard. I spot Russians, Latvians, Italians, Syrians, Egyptians: men with faces dark as a japanned brougham. Their tongue-twister salutations call out to me like the very sirens and I am tugged into their wake.

I stroll through the jumble of stalls. The air is busy with Manchester aromas, surpassing all the perfumes of Arabia: treacle tarts rub up to meat puddings; tureens of pea soup steam alongside pyramids of oranges so vivid they sting your eyes; buns and barms are hawked cheap by the stale sackful. Butchers bawl their bargains. Despite the reek of meat left standing all day like a tart with no takers, there’s still a pack of ravenous crones haggling over tongue and cow-heel, tripe and heart.

A pie stall tantalises. I’m hungry enough to eat a horse, which is as well for I bet my berries that’s what’s in them. I slap down tuppence and savour my supper under the stars, or the closest Manchester gets to them. I wolf it so fast a scrap of crust catches and I cough. My feet hiccup, the cobbles fly up to meet me and I sprawl, nose-down in muck and grease and God knows what else.

A hand grabs the back of my jacket and hauls me upright. I wrap my hands around my head in case he’s of a mind to clout me, but this stranger has come to my rescue.

‘Careful, lad,’ he roars. ‘You nearly bought it there.’

He jerks his head at the wagon thundering past. It shows no sign of having slowed by so much as an inch to avoid crushing me into cag-mag.

‘Thank you,’ I say, spraying pastry.

My saviour laughs. ‘Next time, save me a bit of pie.’

I lick my fingers. What a fine night this is turning out to be. The older lads and lasses pay me no mind, too busy with their rough flirtations. One girl pauses before the chap of her choice, plucks the flower from his buttonhole and bites off half the petals before crushing it back into its tiny hole. His chin hangs in a gawp as she struts away, earrings swaying, swinging her umbrella like a sword. Another pert miss, hat loaded with more fruit than a costermonger’s barrow, swipes the tea mug from her beau and takes a good long draught before returning it, a crescent of scarlet greasing the rim.

I stick out my chest in the hope of gathering similar attentions. I might, you know. One day. For now, I loiter at the tea-stand, entertained by the music of coarse songs and coarser jokes. I chuckle at the half I understand, laugh louder at the half I do not. Not that it’s only tea in those cups. Tea and a bit will get a fellow a splash from a mysterious jug kept beneath the counter and it certainly isn’t water. I slap down a sixpence, wink knowingly.

‘Hop it, short-arse,’ growls my host. ‘It’s not for little boys.’

‘Get knotted,’ I retort. ‘I’m fifteen!’

‘My arse. When you’re tall enough to see over the counter, then I’ll serve you.’

I’ve a few inches to go. In this world you need to choose your battles, so I screw up the sodden bit of newspaper that held my pie and bounce it off the head of the nearest urchin. He spins about with a glare fit to take the head off a glass of porter, takes one look at the size of me and changes his mind. He rubs his noggin, contenting himself with a scowl. Not that I intend him any harm: it is exuberance, not meanness of the heart.

I’m still ravenous. Coins clink a reminder: Don’t let us go to waste! I splash out on an ounce of cinder toffee. The taste spirits me away to a place of fireworks, a sweet yet bitter recollection and one I do not wish to have in my head. I spit out the muck and the memory with it, shove the remainder into the hands of the little lad. He unwraps the bag, stares at it in disbelief.

‘Take it,’ I grunt. ‘No catch.’

He eyes me like I’m a god come down to earth with a fistful of miracles. In search of fresh diversion I walk on, my adoring acolyte dogging my shadow. Beggars clot shop doorways, hands outstretched, eyes as empty as winter windows. Women gaudy with rouge gear up for a night of horizontal wrestling. Carts are lined up beneath their lanterns, the drovers supping quarts of four-ale. Halfway along the wall, a puppet booth has been set up, ringed by a brood of grubby nose-pickers. Punch is battering Judy against a painted backdrop of pots and pans.

That’s the way to do it, quacks Punch.

I elbow my pipsqueak friend and point at Punch’s beaky nose. ‘See that hooter?’ I say. ‘It’s where he stores his sausages.’

I wait for him to laugh. His mouth hangs open, catching moths, still unable to believe that I gave him an ounce of toffee free, gratis and for nothing. My talents are sorely wasted on some fellows. The play proceeds with the usual thrashing and squawking of blue murder. Judy sprawls on the counter, staring at me with wooden eyes as Punch belabours her.

Take that you shitty-arsed cow! he screeches, employing words not in the regular repertoire. Here’s another, shit-faced old bag.

My little pal tugs my sleeve. His lower lip is trembling. I take a moment to survey the sea of small children. Every last one of them is quivering on the verge of tears. I can’t spot a single mother. They’ve all deserted their babes to go in search of a bottle of stout. It seems I have been left in charge of this ragged army. What a fine general I shall be. I rub my hands, take a deep breath and echo the puppeteer.

‘Shitty-arsed cow!’ I yell.

No one threatens to wash out my mouth with soap. The carters chuckle at my impertinence. I nudge my companion encouragingly. He combs grubby fingers through his hair so that it stands up in an exclamation mark, eyes wide with the realisation that no one’s about to thump better manners into him either.

‘Shitty-arsed cow,’ he whispers all in a rush, in case time runs out on insolence and he is called to account.

The little ’uns screw their heads around from the marionettes and gawk at us.

‘Go on,’ I say, thumbing my lapels. ‘You can shout as loud as you like.’

One girl shakes her head. She fusses with the hem of her pinafore, revealing stockings going weak at the knees. We don’t need her. The rest take my lead, in cautious disbelief at first, then louder, till the whole cats’ chorus are yowling: Shitty-arsed cow, shitty-arsed cow. I am their bandleader, stamping out the rhythm of the words as we parade in a circle. Some bang invisible drums, some clash cymbals, some thrust trombones out and in and out again, all to the tune of shitty-arsed cow, shitty-arsed cow. I am so swept up in the cavalcade that my devotee has to tug my sleeve three times before I take notice.

‘Look,’ he says, pointing.

‘What? Don’t stop now. We are having such larks.’ I holler shitty-arsed cow for good measure.

‘No, look,’ he repeats.

The puppets have been joined by their master, a scrawny man with a nose the shape and size of a King Edward’s, face curdled with bile. He rams Judy face down on to the shelf at the front of the booth and thrashes her with such force that plaster brains tumble like rice.

‘Turd! Turd!’ he shrieks, spittle flying from drawn-back lips.

‘Turd,’ I snicker. ‘He said turd.’

Judy slumps, arms drooping over the cloth. Punch’s red coat hangs in shreds, the whole of his hump and half his knobbled cap broken away. The backdrop tangles around the puppeteer’s arm but he continues to whack the puppets against each other, screaming obscenity after obscenity.

‘Look at the mess he’s making,’ gasps the boy. ‘Shouldn’t we tell somebody?’

I shrug. I don’t care if he drags the whole tent around his ears. I don’t care if he pulps the puppets into glue and the children bawl their eyes out. Mayhem is my meat and drink.

‘Stop being such a little prig,’ I snap. ‘This is the most fun I’ve had in an age.’

It’s only when every infant is wailing that the drovers put down their pipes and pile in. They cart off the puppet-master, still yelling filth. This must be the best, most roisterous, boisterous night known to man or boy.

I am encircled by dirty faces, agog for the next game. I am so engaged with racking my brains that I do not notice the bigger lads until I’m surrounded. One by one my midget congregation melt away, leaving me alone with this new gang. At first they ignore me, busy punching each other in a comradely fashion, although one of them strikes with far more vicious intent than the others. I’m glad he’s not whacking me. Though not the tallest, he carries the mantle of king upon his shoulders. He also wears a black eye like a campaign medal.

‘That’s some shiner you’ve got there, Reg,’ says a lad with a face like a ferret and hair to match.

‘It is indeed, Wilfred,’ says Reg.

Quicker than a bolt of lightning, Reg thumps Wilfred in the guts. He doubles over, wheezing. No one dares go to their comrade’s aid, for fear they’ll be next in line for similar treatment.

Reg chuckles, the sound of a dog being strangled. ‘You should see the other fellow.’

The gang snigger timidly and I join in. It is a mistake. Reg twists his head in my direction.

‘Who are you, pipsqueak?’ he says, legs apart, hands deep in his pockets and pushing out the front of his trousers.

‘I’m Gnome, that’s who I am,’ I say with as much of a swagger as I can muster.

He grins, his teeth sharp and grimy. ‘Where did you crawl in from? Never seen you before.’

‘You have,’ I snort. ‘Here every night, so I am.’

‘Are you now?’ he replies. He turns to his companions, who form a circle. ‘He says he’s here every night.’ They snicker, sharing the joke I am not privy to. The ring of bodies tightens. ‘I’m in charge here,’ Reg declares. ‘Time for you to step away, and step lively.’

‘Don’t see why I should,’ I reply, fists in my britches. He’s not the only one who can thrust out his nackers.

Wilfred lurches forward. ‘How dare you talk to Reg like that,’ he snarls, still cringing from the blow he received from the man in question.

I wither him with a pitying glance. Poor sap, if he thinks having a pop at me will restore him to his master’s good books. His face reddens.

‘You little—’ he growls, aiming a punch. ‘Show some respect!’

I duck, quickly enough to avoid a broken nose, too slow to save my cap from being knocked off. Curls tumble as far as my shoulders. There’s a pause. I retrieve my hat from the cobbles, shove it back on my head.

‘My my,’ says Wilfred, whistling appreciatively. ‘What have we here?’

‘Don’t know what you mean,’ I grunt, tucking away hanks of hair.

‘You’re a girl!’ he hoots.

‘Don’t talk soft,’ I reply with a snort of derision. I turn to Reg. ‘Are all your lot this daft?’

It is another mistake.

‘Wilf’s got a point, for once,’ says Reg. Wilfred preens in the glow of approval. ‘Maybe you are a girl.’

‘I’m bloody not.’ I hawk and spit. My mouth is dry and I barely make a mark.

‘Let’s have a better look at you,’ Reg murmurs, stepping close. I smell gin, so strong and thick you could wring him like a dishcloth straight into the bottle. He grabs one of my ringlets and rubs it between his fingers. ‘I declare. You’re a proper Bubbles.’

‘Don’t call me that.’

‘Bubbles!’ squawks Wilfred.

‘Shut up!’ I cry.

‘I’ll call you what I like,’ leers Reg. ‘You’re a genuine, certified Pears advertisement.’

He circles his thumb and forefinger and blows through the hole. Another chap cracks the brim of his boater, conjuring it into a makeshift bonnet and puckering his lips for a kiss. Another picks up the hem of an imaginary skirt and prances around me. One after the other, they join in the pantomime.

Bubbles!

Bubbles!

What a dainty little damsel, all sugar and spice.

Round and round they go, Reg chasing after and growling like a bear. If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em, so I clap and cheer, loud as the rest. I’ll show them I’m the kind of fellow who can laugh at himself. I’d be a welcome addition to their number. With the suddenness of a thunderclap, they stop. I stop also, but a second behind. They stare at me, chests heaving.

Reg draws his hand across his mouth. ‘Who said you could laugh?’

‘No one,’ I mumble.

A chill crawls down my thighs, right to my boots. Reg pokes me in the chest.

‘You’re laughing at me, aren’t you?’

‘No sir!’ I exclaim.

I stumble under the assault of his finger. Someone kicks my legs from under me and I drop to my knees, hard and heavy as a sack of turnips. Wilfred wrenches my arms behind my back and holds them tight. Reg presses his nose to mine. He has sharp eyes that see through me as easy as through a piece of glass, right to the other side.

‘You little shit. Asking for trouble, aren’t you, eh?’

‘You tell him, Reg,’ says Wilfred, his expression even more weasel-like, if that were possible. ‘How about a new game?’ he murmurs in Reg’s ear. ‘A man’s game.’

The world breathes in, like that moment before a storm begins. I hold particularly still.

‘There’s a thought,’ says Reg.

He unbuttons his fly with luxurious deliberation, licking his lips to ensure I am paying close attention, which I am. He slides his hand into the gap and draws out his porker. It’s near long enough to tie a knot in. The other lads grin, their eyes slick with knowing.

‘A proper man’s pipe, that’s what I’ve got. How’d you like to blow bubbles on this?’

I try not to breathe. I mustn’t show I’m spooked. If he smells fear who knows where this may end?

‘Even better, how about a ride on Jumbo?’ he purrs. He tugs his pocket linings inside out. They look uncommonly like elephant ears. ‘Little girls like a circus ride.’

His coven giggle, wheezing like witches. It takes every ounce of courage to affect an air of boredom. I roll my eyes lazily and shuffle away.

‘Not so fast,’ leers Wilfred.

He wraps his arm around my throat, shoving his nadger into my spine. It’s rigid and I’m damned if I can understand why. I have no leisure to solve the conundrum, for I am far too exercised by having the life crushed out of me. Reg swings his hips from side to side and his sausage swings too. He takes a lumbering step forward.

‘Come on,’ he says. ‘Only a penny a ride.’

‘That’s a bargain,’ says Wilfred.

‘Cheap at half the price,’ quips another, until the whole nasty lot are egging him on.

‘Put him down!’ blares a woman in a hat as broad as a soup tureen. She waggles her finger in the direction of Reg’s privates. ‘You can put that away and all.’

‘Says who?’

‘Says me, Reginald Awkright. He’s half your size.’

‘We’re only playing.’

‘You’re throttling him.’

Wilfred tightens his grip. ‘Nah. Bit of rough and tumble, isn’t it, Bubbles?’

‘Tumble!’ I squeak.

‘See?’ says Reg. ‘He loves it, don’t you?’

Wilfred squeezes again, like I’m a set of bagpipes.

‘Yes!’ I rasp.

‘I said, leave the poor mite be,’ she snaps. ‘He can’t hardly breathe. I know your sort, Reginald.’

He lets out a whickering laugh. ‘I know your sort and all, Jessie, you wet-kneed slapper.’

The remainder of their banter is lost in the roaring between my ears. Reg and his rabble seem a long way off. Or rather my head seems a long way from them, detached from the neck and floating away. It is most peculiar, very like the feeling I get when I – she—

I splutter into myself. ‘Get off me!’ I shriek.

Whether it’s the command in the woman’s voice, or the shock of me fighting back, I’ve no idea, but Wilfred loosens his stranglehold. I tumble forwards, giving my elbow a blinder of a crack and half stagger, half crawl away as fast as I can. Jessie picks me up as easily as you might a dropped glove. I don’t cling to her like a drowning man to a lifebelt. Not me, not by a long chalk. I just need to steady myself on her arm, that’s all.

‘There you go,’ she says, setting me upright. She rounds on the gang. ‘As for you lot, play nicely or bugger off.’

She commences patting dirt off my jacket. She smells of trapped violets.

‘I’m all right. Don’t need help,’ I say half-heartedly.

‘You tell her,’ jeers Reg. ‘See? He doesn’t want you, you old whore.’

The boys snigger at the insult. I wait for the blubbing to start. But she tips up her chin with something that looks uncommonly like pride.

‘Don’t you just wish you could get a morsel of what I’ve got to offer!’ she hoots.

‘As heck as like,’ snarls Reg. I’ve never seen a man’s eyes so famished. He points at me. ‘I wouldn’t touch you with his,’ he declares.

Jessie furnishes us with a bray of merriment, turns with extravagant grace and promenades into the throng. I watch her go, mightily impressed. I’ve no idea why Reg called her old, either. She’s as pretty as a picture. The sort of woman a chap would be proud to have on his arm. However, I have precious little opportunity for approbation.

‘Just like a girl,’ he growls. ‘Ganging up on us.’

‘I’m not a flaming girl,’ I sigh with wearied emphasis. ‘You blind or brainless?’

‘You cheeky little sod. You are what I say you are.’

‘That’s right,’ says Wilfred, still determined to get on the right side of Reg. He grinds his fist into his eye socket. ‘Run to Mama,’ he whines. ‘Wah, wah, Mama!’

Reg twists his unpleasant attention from me to Wilfred. My face cools as the awful heat is taken away.

‘Who are you calling Mama?’ he says.

‘I didn’t mean you, Reg, old pal. I mean her.’ He stabs a finger in the direction of Jessie. She’s long gone and he is pointing at a vacancy.

‘I don’t see anyone.’

I concentrate on making myself unnoticeable. Things could still change in a heartbeat.

‘It’s a joke,’ Wilfred blusters.

‘I know what a joke is,’ Reg says. ‘You saying I don’t?’

‘No! Never!’

Reg inhales slowly and glances at me. I’m out of arm’s reach. Wilfred isn’t. ‘You saying I’m like that old tart?’

‘Yes,’ I whisper. ‘Sounds exactly like what he’s saying.’

There’s a horrified silence. No one drops so much as a giggle into it. Reg jabs a rigid finger into Wilfred’s chest. He reels backwards like he’s been hit with half a house brick.

‘No!’ he wails. ‘It was a joke! I didn’t mean you! We’re chums, aren’t we?’

Reg roars and at the signal the whole lot of them pile on to their new enemy. I don’t hang about to see the outcome. My conscience pricks briefly about dropping Wilfred into it, but it was him or me. I show the cleanest pair of heels this side of the Mersey and run slap bang into the lady who saved me. Of course, she didn’t exactly save me. I did that for myself.

‘Mind where you’re going!’ she chirps. ‘Oh, it’s you. You all right?’

‘Course I am,’ I mumble. ‘Why wouldn’t I be?’

She ought to tell me to get lost and I don’t know why she doesn’t. She ruffles my hair. I rub my head against her hand like a cat that aches to be scratched. Her fingers comb through my curls.

‘Bonny lad,’ she purrs.

The words startle me back into my skin.

‘Leave off!’ I squeak. ‘I’m no one’s bonny anything!’

I untangle myself from her skirts and fire homewards like a rocket. The kitchen is busy: Grandma sucking on that disgusting pipe of hers and Mam waving her hand and muttering, What a stink. Not that Grandma takes a blind bit of notice. So much for the welcoming bosom. After the night I’ve had a smile wouldn’t go amiss. I help myself to a slice of bread and dripping, plonk myself in front of the range and stare at the coals. I can’t go back to Shudehill. Reg will make my life a bloody misery. Where else can I go? What else do I have?

‘Is all well?’ asks Grandma, deigning to notice my presence. She taps her pipe on the edge of the table, to another complaint from Mam.

‘Why shouldn’t it be?’ I grumble through a mouthful.

‘Don’t you give me any of your lip,’ she replies.

‘You leave him alone,’ chips in Mam without looking at me. ‘He’s my special treat, so he is.’

‘It wouldn’t hurt to hear you saying that about Edie once in a while.’

Mam snorts. ‘Her? I wish things were the other way around.’

‘That’s half-daft. How can you dote on one and not the other?’

‘I’ll do as I please, thank you very much. All any mother wants is an honest-to-goodness son to do her proud. If you don’t like it, there’s the door and remember to shut it behind you.’

I scoff my bread, looking from one to the other. Biddies. I’ll never unravel the mare’s nest between their ears. But what I do hear is an advantage I didn’t know I had. I lick my fingers and leave them to it.

The bedroom sash is open. I clamber through the gap and ride the stone saddle of the windowsill, one foot in and one out. The sky is becoming pale as it considers the coming morning. I puff out my chest, draw the last scraps of night into my body until there’s no telling us apart.

There was a time.

I’ve not forgotten that land of sweet content, bright as a favourite story told at bedtime. Things aren’t the same since Edie got frozen into an obedience she imagines will thaw our flint-hearted mother into loving her. You may as well try to fold gravy. Mam can’t stand baa-lambs unless they come smothered in mint sauce.

Edie’s worse than a mouse; at least mice chew the walls and confetti the floor with their tiny turds. Her goodness clings like quicksand. If I get sucked in, it’ll be curtains. Every night I step close and try to take her hand, like we used to, but our fingers slide through each other. It’s like she doesn’t believe in me; like she thinks I’m not real. I don’t know what more I can do.

My chest is hot and tight. I grind my teeth until the feeling passes. If you’ve been booted out of Eden, moping like a snot-nosed toddlekins won’t bring it back. I will not think about things I can’t have. Fairy tales are for the cradle and I left that a long while ago.

Living in a houseful of women has dragged me down to their simpering level. I must toughen up if I’m going to make my way in this wide world. I’m not a bad lad; not the type to tie cans to a cat’s tail, string them up by their paws, set them on fire or any one of the bloody things boys do. But there’s no point being soft. In this life, you’re either a ginger tom swaggering the streets or a cowering kitten that gets trampled underfoot. I’ll let tonight be a lesson. My fault for not standing my ground, for being caught unawares. God helps those who help themselves.

I’m not lonely. Not by a long chalk. I just need to meet the right fellows, that’s all. The sort of pals who will stick by a chap through thick and thin. So what if I have to go to ground for a while? I’ve got tomorrow night, even if I have to steer clear of Shudehill. There’s always another night. There has to be. A man must have dreams.