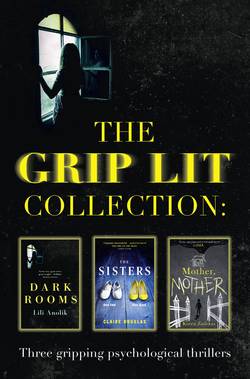

Читать книгу The Grip Lit Collection: The Sisters, Mother, Mother and Dark Rooms - Koren Zailckas, Claire Douglas - Страница 25

Chapter Nine

ОглавлениеIt takes me a few seconds to register that I’m at Beatrice’s house when I open my eyes the next morning. The tinny sound of a radio playing floats up from somewhere within the bowels of the house and the sun’s rays filter through the gap in Jodie’s threadbare navy-blue curtains, creating oblong reflections on the ceiling. I gaze up at the shifting patterns, unsure of what to do, how to act, now that I’m finally here. It’s been so long since I’ve lived with people my own age, my peers, that I’m immobilized with a kind of stage fright.

I wince with embarrassment when I remember last night and my overreaction to Lucy’s lost letter. I had been so convinced that Beatrice had taken it, to punish me for the growing feelings she must know I have for Ben, that I could hardly concentrate on a word she was saying as she helped me unpack afterwards. If she noticed my odd behaviour, she did a good job of pretending otherwise as she sipped her red wine and exclaimed about the state of my wardrobe and how we had to go shopping for some new clothes. ‘You’ve got nothing but ripped jeans, holey jumpers and baggy T-shirts, Abi.’ When she finally left me alone to go to bed, throwing me a concerned look over her shoulder as she closed the door behind her, I slumped in the middle of the bedroom, hugging my knees, surrounded by a fortress of empty cardboard boxes. Sweat bubbled above my eyebrows and top lip, my heart racing so much that I began to think I might die. In the end I was so petrified I dialled Janice’s number, even though it was past midnight.

She talked me down, assuring me it was only another panic attack, reminding me of all the coping mechanisms she had taught me. ‘Believing that Beatrice would steal Lucy’s letter is your way of punishing yourself because you’re happy,’ she explained in her usual calm, logical way, her soothing voice coating my frayed nerves like antiseptic cream on a graze. ‘And you feel guilty for being happy. It’s called survivors’ guilt, Abi. We’ve talked about this before, remember? It’s a symptom of your post-traumatic stress disorder. Don’t let these destructive thoughts ruin your friendships.’

I know now, in the cold light of day, that Beatrice isn’t cruel, that she wouldn’t deliberately try and hurt me. She would surely know how important those letters are to me. I’ve got a bond with Beatrice, she’s been amazing, allowing me to become part of her life. It is as if she knew, even at our first meeting, how much I needed her friendship. I have to trust her; that was Janice’s advice last night. I have to allow myself to get close to people and allow them to get to know me.

My mobile buzzes on my bedside cabinet and I shuffle to the edge of the bed, turning on to my front to reach out and retrieve it, pleased when I see it is a text from Nia asking how I am, and my heart sinks when I remember that I haven’t told her about my new living arrangements, knowing she will be sceptical and worried for me. I sit up, resting my head against the uncomfortable iron headboard, bunching the duvet up around my armpits as I dutifully reply, telling her I’m fine and will ring her in a few days. Putting off the inevitable.

Wrapping myself in my grey velour dressing gown I scurry to the vast bathroom across the hall, relieved when I don’t bump into Beatrice or her brother before I’ve had a chance to clean my teeth and wash my face. The utilitarian white tiles are cold against the soles of my feet and I stare at my bleary-eyed reflection in the large mirror, wiping away the remnants of last night’s mascara from under my eyelashes, assessing the all too familiar gauntness of my face, of her face. I drag a brush through my blonde hair, noticing my widening parting and the hint of pink scalp beneath, the side effects of stress and the prescription drugs I wash down my throat every day.

I make my way down the many flights of stairs and my disappointment grows with each step when I fail to bump into Beatrice or her brother. Apart from the lachrymose tones that I recognize as Lana Del Ray’s, growing louder as I descend, the house is quiet. It sounds as if the music is coming from the kitchen and I hope that Beatrice or Ben is there waiting for me.

When I get to the hallway and pass the reception room that used to house Jodie’s three-headed sculpture, a flash of colour makes me stop and double back on myself. Popping my head around the door I’m surprised to see that the walls have been painted an acid lime green that perfectly contrasts with the bright white ceiling and coving and, instead of Jodie’s sculpture dominating the room, in its place is a huge leather sofa and a desk. Before I know what I’m doing I push the door open further. It’s a stunning room with doors that lead out on to a long and neatly manicured rear garden. I go to the desk that’s been pushed up by the wall. Some of Beatrice’s earrings and necklaces have been laid out as if on display in a boutique and my eye catches a familiar yellow, daisy-shaped earring and I pick it up, recalling that it was the one she wore when we first met. I hold it in the palm of my hand, marvelling at the way she has designed the flower, so intricate, so delicate. I fold my fingers around it and close my eyes, letting the memory of the first time I saw her linger like the unforgettable lyrics of a love song, and I fight the sudden urge, the sudden need, to put it in the pocket of my dressing gown. I touch the necklace at my throat, the one I never take off, reminding myself I have a little piece of Beatrice already, and I place the yellow earring back on to the top of the wooden desk where I found it. Then I notice the bracelet. It’s stunning, interspersed with sapphires, but a few of the stones are missing, as if she hasn’t quite finished it yet. As I leave the room I think how lucky Beatrice is to have all this: the house, the money, the talent, and most importantly, her twin.

The music gets louder – Lana Del Ray has been replaced by the Arctic Monkeys – as I round the stairs to the kitchen and when I get to the bottom step I jolt in surprise. I’d been expecting, hoping, that one of them would be here, waiting for me. But the only person in the room is a short, rotund woman with a greying blonde bob whom I don’t recognize. She seems oblivious to me as she leans over the table so that her large, heavy breasts, encased in a floral apron, are almost touching the wood as she quickly, and quite aggressively, kneads dough.

A glance at the kitchen clock tells me it’s just gone ten. I clear my throat to announce my presence and the woman looks up. Her eyes are small and dark, two currants in her rounded fleshy face, which is the colour of the dough that she is vigorously kneading.

She swivels on chubby ankles to turn down the Roberts radio that sits on the worktop behind her and her small eyes sweep over me, no doubt taking in my state of undress. ‘Ah, another one,’ she says in a thick accent that I guess has its origins somewhere in Eastern Europe, although I can’t be sure. ‘You are like little stray dogs,’ she says, not unkindly. ‘Pretty little stray dogs. You girls, you come and stay a while and then you go, never to be seen again …’ She shakes her head as if she’s trying to displace the memories of these ‘girls’.

I want to tell her I’m not planning on going anywhere and to ask her who the hell she is anyway, and why is she making what I assume is bread in Beatrice’s kitchen. (I can’t help but think of the house as Beatrice’s even though I know it belongs to Ben as well.)

‘I’m Abi,’ I say as I shuffle towards the table, the tiles sticky under my feet, pulling my dressing gown around me and suppressing a shiver. The large sash window is open and, although the day is warm, the kitchen is cold due to its basement location, deprived of the sun that blazes outside.

She smiles enigmatically but doesn’t offer her name. Who are you? I want to shout, and what are you doing here?

‘Where are the others?’ I ask instead.

‘Ah, the others,’ she replies as she digs her elbows vigorously into the dough. ‘They are out playing tennis.’

I feel a stab of hurt that they would go off and play tennis without asking me.

She goes to the Aga and, kneeling in front of it, places the bread tin carefully in one of its four compartments. ‘Shall I make you a coffee?’ She stands up, wiping her hands on the skirt of her apron. I nod gratefully, muttering my thanks, making sure I take a seat opposite the entrance to the kitchen so that I can see them as soon as they return from their game of tennis. I listen as she chatters over a different, more upbeat song on the radio, while fiddling with the coffee machine’s intricate workings. She tells me her name is Eva, she’s from Poland and she’s been a housekeeper for Beatrice and Ben for six years, ever since they moved to Bath.

‘The poor lambs,’ she says conspiratorially, as she hands me my coffee cup with surprisingly tiny delicate hands for such a large lady. ‘They were so in need of mothering when I met them. They lost their parents you know, a long time ago.’

I take a sip of my coffee as a surge of anticipation rushes through me that, at last, I might get to find out more about them.

Eva takes a seat next to me and launches into a story of when she first came to work for them. Although her words are heavily accented so that I sometimes miss exactly what she’s saying, I can tell by the relish with which she talks that this woman likes to gossip, and I think that this could work to my advantage.

‘I’m local so I don’t need to live in,’ she explains. ‘But I try to come over every day and make them a meal that they can cook up later or freeze.’ So, the delicious lasagne that we had for dinner last night was one of Eva’s offerings. ‘I also do a bit of cleaning for them,’ she continues. ‘Ben particularly likes things tidy. They have a gardener as well. They do need looking after.’

They’re thirty-two years old, I want to shout. They’re hardly children. But I stay silent, not wanting to interrupt her flow. She pauses and glances at me quickly, and I can see that she’s assessing whether she can trust me. She obviously thinks she can as she goes on: ‘When Beatrice first moved to Bath she seemed very fragile, she would keep bursting into tears, telling me she didn’t know what to do – about what, I never found out. She never told me what happened before moving here, but I got the impression she was running away from something, or someone. This house was in total – how do you say it? – total disrepair?’ I nod encouragingly. ‘She threw herself into doing it up. Spent a year having it modernized – it must have cost her a fortune. Then Ben moved in too and she seemed happier, more secure.’

I’m intrigued to find out who, or what, Beatrice was running from. I find the fact that she has a history that I know nothing about disconcerting. I want to know everything about her, otherwise it makes us little more than strangers. I take a sip of the coffee, savouring its bitter taste. ‘How did their parents die?’

‘I think it was a car accident.’ Another coincidence, another thing we have in common. ‘The twins were babies, maybe toddlers, I can’t remember exactly.’ She frowns. ‘They were brought up by their grandparents and, from what I understand, they were very wealthy. When they died, their money was put in trust for when the twins turned twenty-five.’

So that’s where all their money has come from. That’s how they can afford this magnificent house and why they don’t need to charge any rent.

I think of the three-bedroom semi on a small housing estate in Farnham, Surrey where Lucy and I grew up. It wasn’t a bad place to live, our parents always kept it clean, tidy and cosy and we knew no different, it was our home, but it was worlds away from a house such as this. I imagine Beatrice and Ben as children, the orphan twins, running through large draughty rooms of their grandparents’ rambling mansion with extensive gardens and a sweeping driveway, a completely different type of estate to the one where we spent our childhood.

Eva takes a noisy slurp of her coffee. ‘Now that their grandparents have died they’ve only got each other.’

‘At least they’ve got each other,’ I say, thinking of Lucy.

She nods in agreement, licking froth from her top lip with the tip of her tongue. ‘Yes, but it means they are very protective of one another, of course.’ She regards me over the rim of her cup. ‘They won’t let anything, or anyone come between them.’ Her words sound like a warning.

The patter of footsteps on stone and raised jovial voices prevent her from saying anything further. My heart quickens as Beatrice skips down the stairs carrying her tennis racket, followed closely by Cass, Pam and Ben. She’s flushed, a white tennis skirt skimming the top of her tanned thighs. I try to catch her eye but she doesn’t look in my direction.

‘Bread smells yummy, Eva,’ she says, as if I’m not even here. ‘We’ve had a good game, haven’t we, Ben?’ She reaches up and pulls the front of his cap down so that it covers his eyes and he protests good-naturedly. I look at him, willing him to acknowledge me, relieved when he catches my eye and flashes me one of his lopsided smiles. He’s wearing khaki shorts that come down to his knees and I’m pleasantly surprised by his muscular calves.

‘Morning, Abi.’ He moves away from his sister and much to my delight slides into the chair next to me. The sun has brought out the freckles across his nose and he looks tanned and healthy in a white Fred Perry. I resist the urge to touch him. He cheekily asks Eva to make him a cup of coffee and after a bit of banter about her not being his personal slave she gets up and goes to the coffee machine. I can tell by the way her face lights up when she jokes with him, her accent thickening so I can barely understand her, that she would do anything for him.

Now that we’re all in the kitchen it seems smaller, claustrophobic, and I’m glad of the slight breeze from the open window. Pam stands next to the Aga, exclaiming excitedly about the bread that we can now all smell and Cass joins us at the table. Beatrice languishes in an old velvet chair in the corner, her legs swinging over the arm, chattering away about their tennis match, making me wish I’d been included. I feel exposed, still sitting in my nightwear when everyone else is dressed and has evidently been up for hours. Even though Beatrice is her usual bubbly self as she recounts the tennis match that she and Ben won, the disagreement with one of the teenage girls from the house next door who wanted to use the courts, she avoids looking in my direction, does nothing to acknowledge me at all, and I sense that I’ve upset her somehow and now she’s freezing me out. A coldness creeps down my spine and I involuntarily shudder and glance at Ben, suppressing my hurt.

‘Are you okay?’ he mouths, leaning forward. Cass has taken the seat to my left, but she’s staring into space with a glazed look in her eye. I’ve hardly ever heard the girl speak, except to Beatrice.

‘I’m fine.’ I smile shyly, playing with my empty coffee cup, my tummy rumbling from lack of food.

Beatrice is now chatting to Cass, who goes to sit beside her on the armchair. It’s too small for both of them and Cass is practically on Beatrice’s lap, their legs intertwined. Nauseous, I force myself to look away. Ben’s knee touches mine under the table, sending shockwaves through me so that everyone else in the room is momentarily forgotten.

‘Hey, guys.’ Beatrice’s clear voice reverberates around the kitchen so that we all turn to look at her and Cass squashed together in the armchair. They’re both wearing identical trainers. Dunlop Green Flash. I’ve always wanted a pair.

‘Shall we have a get together tonight? To celebrate Abi moving in?’ She turns to me at last. ‘What do you think, Abi? Would you mind?’ She looks at me expectantly; any animosity that I think I perceived earlier has vanished from her beautiful honey-coloured eyes, replaced by a shining hopefulness.

When I mumble my agreement she squeals and leaps out of the chair. ‘Yay! It will be fun,’ she says, running behind me and wrapping her arms around my neck so that our heads are touching, her pale hair brushing my cheek. She smells salty and sweet at the same time and I can’t help but giggle at her enthusiasm, knowing by now that she will find any excuse to hold a party, relieved at her warmth and I realize with a sickening clarity, that I would do anything to prevent myself from being left out in the cold again.