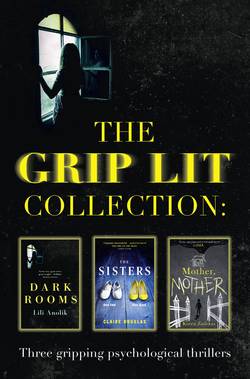

Читать книгу The Grip Lit Collection: The Sisters, Mother, Mother and Dark Rooms - Koren Zailckas, Claire Douglas - Страница 48

Chapter Twenty-Four

ОглавлениеThe tension around my birthday somehow dissipates and the rest of August goes by harmoniously enough. Nia rings me most days, urging me to come to London to live with her, but I tell her I can’t move out. At least not yet, and not without Ben.

I refuse to let Beatrice win.

Beatrice is holed up in her studio, setting stones into silver rings or necklaces; Ben takes on a short contract with a big technical firm along the M4 corridor and I receive more and more commissions from Miranda. On the occasions we are all home, we spend evenings together eating Eva’s homemade cottage pies or casseroles while sharing a bottle or two of wine. Sometimes Beatrice throws an impromptu party, and I’m not surprised when she declares happily one day that she and Niall have started dating. She seems joyful, reminiscent of how she was when we first met. If she’s noticed that I’m sneaking into Ben’s room every night, she doesn’t comment on it, and it’s as if she’s no longer interested, no longer cares what the two of us get up to. On the surface, at least, we are getting along fine, but I don’t trust her completely. I find I’m still wary, still waiting for her next move.

Before I know it, a couple of weeks have passed since my birthday. It seems as though the three of us have found a way to make it work and I’m more hopeful. I say this to Ben one Sunday as we walk around Prior Park Landscape Gardens. The sun is high, the sky a pale blue. Ben tucks my arm in his as we wander along the Palladian Bridge, showing me the names and dates and messages from lovers and friends that have been scratched into its Bath stone columns, marvelling at the inscriptions from over a hundred years ago.

‘I’m glad,’ he says. ‘It’s important to me that my two best girls get on.’ And I feel it, a trace of jealousy. I know I can’t have him all to myself; after all, who better than I to understand their bond? But sometimes their relationship reminds me even more of what I’ve lost. We walk along in silence, both deep in thought, our shadows stretched out in front of us, elongated versions of ourselves, and I’m curious as to what’s going on in his mind, because every now and again he’s like a television that has abruptly been switched off so that I’m no longer able to see what he’s thinking.

As we move off the bridge towards the lake he says, ‘My contract has come to an end, but another company has offered me a job, in Scotland. The money’s good, I can’t turn it down.’

In front of us a mother is grappling with a screaming toddler, trying to hoist him over her shoulder towards the café with the promise of cake. I smile at her sympathetically. ‘How long for?’

‘It’s a week contract, possibly two.’ I can’t bear the thought of being away from him for that long; he’s the anchor to my boat and I worry that I will float out to sea, directionless, without him.

‘Do you need to take the contract?’ I say. ‘What with the trust fund …’

He stiffens. I’ve offended him, wounded his male pride.

‘I’m from a working-class background. It doesn’t seem right not to earn my own money,’ he snaps.

I remember Eva telling me about his rich grandparents, their rambling house on the outskirts of Edinburgh. It doesn’t sound as if it was a very working-class background to me. But I bite my tongue because I can understand how he would want to earn a living and not rely on family inheritance. Since I’ve been working, I’ve been giving money to Beatrice for rent, in spite of her protestations. It doesn’t seem right not to pay my way. I know how Ben feels.

By now we’ve reached the café – or rather a hut with wooden tables set out in front of it, overlooking the lake. The tables are mostly taken up with young families; children run about with ice creams, making the most of the last remnants of summer. We manage to find a small table semi-hidden by an over-enthusiastic bush, with a view of the lake. I take a seat while Ben goes to the hut to buy us coffee.

He returns clutching two takeaway cups with plastic lids and hands one to me as he manoeuvres his long legs over the bench seat opposite. Over his shoulder I watch as a flock of seagulls descend on the lake, foraging for a snack and scaring away a couple of ducks.

‘Will you be okay? In the house with Beatrice and the others? Without me?’ he asks. I’m pleased that he’s worried about me.

‘Everything seems to have settled down, and I’m getting on OK with Beatrice again. It makes life a lot easier.’ He nods and takes a sip of his coffee. ‘All that weird stuff that happened, Ben. It was awful, it was as though I was losing my grip on reality.’

‘I can imagine.’

I shake my head, trying to chase the unwanted memories away. It’s all in the past, I remind myself, I need to forget it.

Ben has been in Scotland for the past ten days, leaving me wafting around the house, unsettled, like a spirit with nobody to haunt. I miss him the most at night, so I sleep in his bed, inhaling the smell of him that lingers on the sheets, imagining him here with me.

On the Friday that Ben is due home I’m sitting at the kitchen table with my laptop. Pam is at the sink washing out brushes; her hair has gone from tarmac black to a blood orange – a home dye job that went wrong apparently, although it has now ‘grown on her’. She’s wearing baggy paint-splattered overalls and is chattering away, totally oblivious to the fact that I’m trying to write an article I promised Miranda. I log on to Facebook, distracted by Pam’s incessant chatter, knowing I won’t get any work done while she’s in the room. As I do every week or so, I go on to Lucy’s Facebook page that I’ve still kept running, not quite able to contact them to disable it, taking comfort from the past posts on her timeline, the photographs she uploaded before she died, the funny messages on her wall that we sent to one another. Her profile photograph is of the two of us, taken at some party; grinning inanely, hair damp with sweat, a crowd of people dancing behind us, slightly out of focus. I smile at the memory, remembering when Nia took the photo at the opening of a new club in Covent Garden. With beads of perspiration on our foreheads, our hair pushed back from our eyes, our lips bare, even I have to scrutinize the photograph to remember which of the smiling, fun-loving girls is me.

The letters in the box upstairs are the only private things I have left of her. Yes, I can access her Facebook page, click on the videos that I have of her, but it’s the letters that mean the most, because in them she poured out her thoughts and feelings. When I read them, I can hear her voice, I can imagine that she’s talking to me. Letter-writing was something we shared, something personal, between the two of us and not for her three hundred Facebook friends. And when I think that three of those precious letters have been taken by Beatrice and hidden God knows where, a flicker of anger burns inside me so intense it takes me a while to calm down and regain my composure. I’m biding my time, but I will get those letters back.

Pam is still chattering away but her words wash over my head. There is something new on Lucy’s timeline, her status has changed. My heart starts to race and I rapidly blink to make sure I’ve read it correctly. But there is no mistake. The three words float in front of my vision so that I’m dizzy.

I’ve been replaced.

My fingers tremble as they hover over the keyboard. I can see by the date that it was written yesterday. My mouth goes dry. Has her account been hacked? Maybe it’s some idiot mucking about, but why write such a thing? What does it mean?

‘Are you okay, love?’ says Pam, noticing my shocked expression.

I can’t bring myself to tell her because, as much as I’m fond of Pam, admire her reassuring presence, her confidence, not even minding that she’s slightly self-obsessed, I doubt she would understand. When I received those flowers on my birthday she had appeared nonplussed, almost dismissive, assuring me there was probably a logical explanation. As if there could be.

So I plaster a tight smile on my face and tell her I’m fine, and she seems to believe it as she gathers up her paintbrushes, humming as she trots up the stairs to the next floor.

Why would you write that, Lucy? I think, before checking myself, tears stinging my eyes as it sinks in that, of course, Lucy didn’t write it. How could she? She’s dead. She’s fucking dead! I take deep breaths, try to concentrate on my breathing. I slam the lid of my MacBook, telling myself that it’s a mistake, that it doesn’t mean anything. That it’s not at all weird, eerie, sick that a message has appeared on my sister’s wall nearly two years after she died.

When I check again later, the message has disappeared, leaving me doubting whether it was ever there in the first place.

It’s dark when Ben’s little Fiat finally turns into the street. I watch from my bedroom window as he pulls up outside the house. I run downstairs, throwing open the front door as he’s stepping on to the pavement. He’s dressed in a moss green corduroy jacket that I haven’t seen before, and a woolly beanie hat pulled down over his head, hiding his hair. Although it’s only the end of August the weather has taken a turn for the worse so it seems more autumnal. I’ve missed him so much. I rush towards him but something about his demeanour makes me hesitate by the wrought-iron gate. He looks tired, the tan he acquired over the summer has faded and his shoulders are slumped. I call out to him and he glances up; his smile, when he realizes it’s me, transforms his face. I open the gate and fall into his arms and he drops his suitcase on to the pavement to hug me. ‘Oh, I’ve missed you,’ he says into my hair as he squeezes me tightly, urgently. ‘It’s been a hideous few weeks.’ I nod sympathetically, remembering his late-night phone calls bemoaning his boss, the ridiculous long hours, ‘the shambolic company’ that he’s working for.

He picks up his suitcase and we go into the house. ‘Where’s Bea?’ he asks. ‘How have the two of you been getting on?’ I assure him that Beatrice has been great, that the four of us have muddled along together quite nicely for the last ten days. And even though Cass is still an enigma to me, I’m used to her quiet ways now, her slinking about the house like a cat; the only person she seems comfortable with is Beatrice. As we go into the kitchen, he asks me if I’ve seen much of Niall and I can tell by his faux air of nonchalance that he is trying to quash his feelings of jealousy, that it bothers him to know he’s not the only man in his sister’s life any more.

As I reheat some of Eva’s chicken casserole for his dinner I tell him that Beatrice isn’t home, that she’s gone to some art gallery with Niall. His face falls and I pretend not to notice, disliking the way it makes me feel. I put the plate of food in front of him and go to the larder to retrieve a bottle of wine. ‘Something tells me you need this,’ I say as I pour him a glass of Chablis. He smiles gratefully, his eyes shaded with fatigue. I pull out a chair opposite him and pour myself a glass too. It’s on the tip of my tongue to tell him about the cryptic message on Lucy’s Facebook page, but he looks so tired, so fed-up that I can’t bring myself to worry him.

Later, when we’re in his bedroom, I go to his Bang and Olufsen music system and I’m about to turn it on when Ben shouts at me, causing me to jump.

‘Don’t touch that,’ he snaps, coming to me and pushing my hand away. ‘It’s expensive.’

I experience a stab of hurt but remind myself that he’s had a long journey, a stressful ten days at a job he hated. He’s just tired, frustrated. It’s become obvious that he’s a little pedantic about certain things; he hates me washing or ironing his precious designer shirts, or touching any of his expensive gadgets. And that’s fine. It’s one of his quirks. It doesn’t mean anything. So I step away and get into bed. When he joins me I go to remove his boxer shorts. ‘Not tonight, Abi,’ he says, shuffling his body to the other side of the mattress. ‘My mind is all over the place. I need to sleep.’ He turns over so that I have no choice but to stare at his back, at the mole in the shape of a four-leaf clover on his right shoulder, and his words send a chill through me.

I leave Ben sleeping the next morning and take the bus into town.

It’s a crisp day, the sky a vivid blue that borders on violet, and the clouds float past a little too fast, suggesting rain is on its way. I wrap my chiffon scarf higher up my neck as I get off at Bath Spa bus station and head towards Milsom Street. I’ve seen a pair of ankle boots that I want to try on; now that I’m earning more money, I can afford to buy them. I’m walking with my head down, hands thrust into the pockets of my parka, my mind full of Ben and what could be troubling him, and I don’t see the woman heading towards me until I almost bump into her.

‘Sorry,’ I say, looking up. Jodie is standing in front of me, dressed in a puffa jacket and grey skinny jeans, a smile on her usual sulky mouth. ‘Jodie, how are you?’ She’s carrying a leather rucksack on her back that looks like a large beetle.

She stares at me and I can see that she’s trying to place me, working out where she knows me from, and then her eyes light up as it finally dawns on her who I am. ‘Abi, isn’t it? How’s it going, living with the freaky twins?’

I’m irritated at her disloyalty. ‘They’re not freaky.’

She laughs but it sounds hollow, insincere. A woman tries to step past us on the narrow pavement and tuts. I apologize and move aside, Jodie follows suit. The faint spittle of rain kisses my cheek. Even though I don’t warm to Jodie, I ask her if she’s got time for a quick coffee, that I would like to ask her some questions. She ponders my offer, and I can see her weighing up what to do. I can tell that part of her would love a good gossip about the ‘freaky twins’ as she calls them, but the other part is wary about getting involved, about saying something that could get back to them. In the end she agrees and we head into a coffee shop near the Roman Baths.

We grab the only empty table left upstairs, sinking into the chairs in relief. Jodie removes her backpack and shrugs off her Michelin Man coat. By now the rain is thrashing against the windows in a fury, the café is packed and the shared breath of strangers and steam from hot drinks has caused condensation to smear the windows.

‘It always seems to rain in Bath,’ says Jodie, surveying the downpour. ‘Anyway,’ she takes a sip of her caramel latte, cursing that it’s too hot. ‘What did you want to talk to me about?’

‘Look,’ I say, leaning forward conspiratorially. ‘Do you remember what you said to me? That day in your bedroom? You warned me to “watch my back”.’

She shrugs. ‘Yeah. So what?’

‘What did you mean?’

She narrows her blue eyes. ‘Why do you want to know? Has something happened?’

‘You’re still friends with Cass, right?’

‘Yes,’ she says haltingly. ‘What’s all this about?’

‘But you fell out with Beatrice?’ I ask, ignoring her question.

She sighs and she looks young to me then; she can’t be much more than twenty. ‘When everyone first meets Beatrice they fall under her spell. She’s beautiful, funny, talented, smart.’ She could be talking about Lucy. I nod encouragingly, sensing that there’s more she wants to say. I’m right. ‘But she picks people up and drops them when she’s bored of them. Have you not found that out by now?’ I can sense in her an unspoken hurt at being left out in the cold.

‘I’m not sure,’ I admit. ‘My feelings for Beatrice are complicated.’

‘Are you in love with her?’

I almost spit out my coffee in shock. ‘Of course not. Why do you say that?’

‘Oh, everyone falls in love with Beatrice. Cass is absolutely smitten.’

‘Cass?’

‘She’s gay. Didn’t you know? She’s totally in love with Bea, follows her everywhere, won’t hear a bad word about her.’

Now it all makes sense. How could I have been so blind?

She takes a noisy slurp of her coffee. She’s wearing a baggy black T-shirt of a band I don’t recognize and, as I assess her from across the table, I think that she has a pinched kind of face as if she’s always cross, even when she’s smiling. ‘I fell out with Cass when I left. But we’re friends again now. She can’t help her infatuation, can she?’

‘Do you think Beatrice is that way inclined?’

‘They did have a thing a while back. They thought nobody knew, but I did.’ Something tells me that not much gets past Jodie. I feel a twinge of … what? Excitement at the thought of the two of them together? Regret that it was never me? ‘But Beatrice is messed up. She told Cass that some guy broke her heart when she was at university, that she’s never gotten over it. And the way she is with Ben, so possessive, it’s weird.’

‘What do you mean?’ I’m still reeling about the lesbian revelation.

‘Come on,’ she scoffs. ‘I don’t know exactly what’s going on there, but something isn’t quite right. She has a hold over him, I know that much.’

I sit up straighter, expectantly. I long to tell her what’s been happening since I moved in, how I believe that Beatrice is probably behind it, that it’s all stopped now she’s met Niall – until yesterday. But I keep my mouth shut. I don’t trust that Jodie won’t go blabbing to Cass. ‘What makes you say that?’

And then she tells me.

A couple of weeks before she moved out she overhead them talking – ‘I wasn’t eavesdropping,’ she insists, although I suspect she probably was. She was coming down the stairs when she heard raised voices from the drawing room. Ben was agitated, she could hear him pacing. Beatrice was stretched out on the sofa. She could see her bare legs, crossed at the knee, and her hands clamped around a glass of wine, through the half-opened door. ‘He was shouting at her, telling her that nobody could ever find out, that she had to promise not to say anything to “her”. I’ve no idea who the “her” was. He alluded to some crime, something from their past. I was scared, Ben sounded out of his mind with worry. And Beatrice … Well, she just sat there, almost teasing him, as if she enjoyed having this secret with him. I got the sense that he was a lot more worried about it getting out than she was.’ Jodie pauses, making sure she’s got my undivided attention. She has. ‘But the weirdest thing was, I’m sure he called her Daisy. If it wasn’t for the fact I recognized her voice, saw those legs and that tattoo around her ankle, I would have assumed he was talking to someone else.’

‘Daisy?’ I frown, remembering. ‘That was their mother’s name.’

Jodie shrugs. ‘I dunno. Anyway, I must have made a noise on the stairs because Ben threw the door open and caught me listening, his face …’ She gives a theatrical shudder. ‘He was furious. He snarled at me, insisting I tell him what I’d overheard. He didn’t believe me when I played the innocent. After that, Beatrice made it difficult for me to stay.’

‘In what way?’

‘Oh, I expect you’ve had the cold-shoulder treatment. I imagine you know what that’s like.’

I smile tightly, suddenly feeling an affinity with Jodie because she’s right: I know exactly what that’s like.

When I get back the house is empty. I run up to my room and start up my laptop, logging on to Facebook and go straight to Lucy’s page.

There are no new words on her timeline but there is a link to a photograph. I click on to it and gasp as her face comes into focus, filling up the screen. It’s the black-and-white, head-and-shoulders shot of Beatrice wearing her own jewellery. The photo that Cass took for the website. I remember the words from yesterday, I’ve been replaced. I never knew what that meant before but now, alongside the photograph, I understand. I laugh, relieved. I’m not going mad. My illness hasn’t returned.

Somebody has been playing with my mind on and off since I moved in. Now I know who.

It’s always the quiet ones.