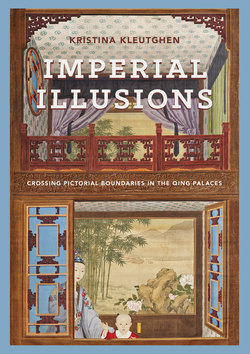

Читать книгу Imperial Illusions - Kristina Kleutghen - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNow mounted as a hanging scroll in imperial yellow brocade, this small painting was originally executed in a format that seems to have appeared only in the Qing dynasty.17 “Affixed hangings” (tieluohua, literally “apply-and-remove paintings”) are typically small to medium-sized paintings or calligraphy that are often bound around the edges with a strip of fabric or paper and affixed directly to walls without any attendant mounting. China has a long native tradition of monumental illusionistic murals that share some important similarities with scenic illusions, but scenic illusions are not murals painted directly on walls. Instead, they are a variation on affixed hangings. These significantly larger and heavier versions were produced on multiple pieces of silk joined smoothly together, often with thick backing paper applied for strength and stiffness before being affixed to walls and ceilings. In at least one case, scenic illusions were even mounted on woven bamboo support structures installed onto the surfaces of the walls, perhaps to help minimize the effects of a building’s shifting and settling on the painting, and therefore to maintain the illusion.18

Although the small affixed hanging of Spring’s Peaceful Message did not cover an entire wall in the Hall of Mental Cultivation as the scenic illusion does, and the two works are not known to have been simultaneously mounted in the hall, the smaller affixed hanging painting was originally installed there and inspired the much larger illusionistic work. Today, the scenic illusion of Spring’s Peaceful Message remains in situ on the westernmost wall of the Hall of Mental Cultivation, but what little scholarship it has received has considered it only as a tangent to the small hanging scroll version.19 Yet the two are inseparable, and the introspective poem with which Qianlong inscribed the Spring’s Peaceful Message scroll is also applicable to the scenic illusion:

Portraiture was the specialty of Giuseppe Castiglione,

Who painted me during my younger years.

Entering the room, this white-haired one

Did not recognize who this was.

Inscribed by the emperor in late spring 1782.

This poem has typically been interpreted as a commentary on how Qianlong, grown wrinkled and portly at age seventy-two, after nearly five decades on the throne, barely recognized the slim young prince in the scroll as his former self. However, when read as applying to both the scroll and scenic illusion versions of Spring’s Peaceful Message, the poem, in another negation of phenomenological doubleness, implies two layers of initial misrecognition. Not only had Qianlong aged so much that he did not recognize his younger self in the painting, but the scenic illusion also deceived him into misperceiving the view as real.20 It was extremely uncommon to inscribe a poem on a scenic illusion, not least because of its difficulty but more importantly because an inscription would have destroyed the all-important illusion. Instead, as in this case, related poems were