Читать книгу The Suburban Chicken - Kristina Mercedes Urquhart - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

I grew up with chickens, but not in the way you’re thinking. Born and raised on the island town of Key West, Florida, I rubbed elbows with all manner of feral fowl in the days of my youth. The small, scrappy birds that freely roam the island are descended from Spanish fighting cocks that were smuggled into the United States by way of Cuba. They bred with domestic laying chickens that had been freed during the postwar supermarket boom, when households starting buying their eggs instead of raising them. These wild Key West chickens still own the streets today, indiscriminately roosting in palms and brooding their babies under brush year-round, prey only to the six-toed Hemingway cats that also call the island home.

I grew up with these birds quite literally in my backyard, entirely unintentionally. They were always underfoot, roosting overhead, or, at their best, blocking traffic across town as the proverbial chicken crossing the road. My grandmother, on the other hand, having grown up in Key West as well, intentionally raised these very birds. Learning from her mother, she helped care for the flocks of chickens and pigeons that provided the family with meat and eggs. As a girl, my grandmother was entrusted with the chores of plucking the processed pigeons and egg collecting. Raising your own food was sustainable. It was healthy eating close to home. It was a way of life. And after all these years, it’s a way of life that I’m aiming for as well.

Fast-forward many years and I’m 25, sitting on the couch watching television. I’m living in Brooklyn, New York, with my husband, paying all too much in rent for our tiny ground-floor apartment. I’m watching a home improvement show geared toward sustainability, taking mental notes of what I want to include in our dream house, when the homeowner leads the show’s host out to the backyard. Here she has a small triangular structure on the grass with a few chickens pecking around inside. She describes her birds (naming each one, of course) and how they fertilize her soil as she moves her “tractor” around the yard.

“Ian!” I yell, though it’s completely unnecessary in our 600 sq. ft. (56 sq. m) apartment, “Come look! We’re going to do this when we move. We’re going to get chickens!”

This idea—keeping my own chickens for eggs—excited me more than any recessed light fixture or built-in. I wasn’t exactly sure what it meant, or what the larger implication was to be, but I knew I was hooked before we had even started.

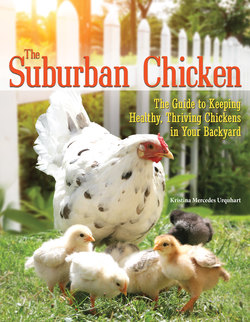

Key West chickens are some of the most colorful feral chickens in America.

When my husband and I finally mustered the gumption to quit our salaried city jobs and move out of New York, we bought our first house in his hometown in North Carolina. Erecting a coop and getting chickens was one of the first things we did in our modest backyard. We raised that first flock from day-old chicks, as we have each of our subsequent additions, and named each one after characters in Beatles’ songs (Loretta, Lovely Rita, Prudence, Sexy Sadie, Michelle, Polythene Pam, among others). Feeling bold, we even named one Easter Egger Yoko, just to be contrary. She’s easily the quirkiest chicken in our flock, and even now well into her prime, Yoko is still one of our best layers. Having our “ladies” in the backyard was addicting; with little effort and a short walk outside, the freshest eggs I’d ever tasted were literally within arm’s reach, any time I wanted them.

It soon became apparent that keeping chickens leads to a certain way of life. What else could I procure from my efforts and my homestead? Produce? Fiber? Fresh milk? In the interest of living more fully from our land and applying a bit of elbow grease, new additions made it to our homestead each following year. Soon, we were spending our summers elbow deep in honey, tending to hives of honeybees. We filled hutches with Angora fiber rabbits, taking hours to harvest wool gently by hand. One year, we started a vermicomposting bin full of red wiggler worms to turn kitchen waste into rich fertilizer. We blamed this new lifestyle almost entirely on the chickens; they had been the catalyst for changing the way we saw food and other basic products that we were taking for granted. Without too much exaggeration, you might say they encouraged us to move away from New York. Soon, we had dubbed chickens “gateway livestock” as they had opened the door to this ever-growing menagerie of furry, feathered, fuzzy, and buzzing charges that changed the way we ate.

Most of the homestead additions had slowed by the time our first child was born, though. Her first bites of solid food came from squash grown in our soil; her first (and only) eggs were from our flock of chickens (thank you, ladies). With our daughter’s presence and increasing involvement around the homestead, it became very clear that we were doing everything we were doing for her and for the next generation of stewards of the land. My hope is that our daughter, like my grandmother, will grow up with respect for the animals that provide her with food and with a hands-on experience that garners the deepest gratitude for those beings.

There is a revolution happening in America, folks. It’s taking place in backyards all across our country’s cities and suburban neighborhoods. Americans are reclaiming the rights to which foods make it onto their plates. They are recognizing their inherent freedom to eat healthy foods, to know where it comes from, and most importantly, to teach the next generation that they can eat well and feed themselves, with their own two hands, by caring for the land. And in my opinion—and experience—that begins with chickens.

A feral hen and rooster pair roam the streets of Key West, Florida.