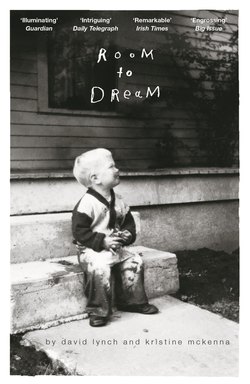

Читать книгу Room to Dream - Kristine McKenna - Страница 12

ОглавлениеSmiling Bags of Death

Philadelphia was a broken city during the 1960s. In the years following World War II, a housing shortage, coupled with an influx of African Americans, triggered a wave of white flight, and from the 1950s through the 1980s the city’s population dwindled. Race relations there had always been fraught, and during the 1960s black Muslims, black nationalists, and a militant branch of the NAACP based in Philadelphia played key roles in the birth of the black power movement and ratcheted up tensions dramatically. The animosity that simmered between hippies, student activists, police officers, drug dealers, and members of the African American and Irish Catholic communities often reached a boiling point and spilled over into the streets.

One of the first race riots of the civil rights era erupted in Philadelphia less than a year and a half before Lynch arrived there, and it left 225 stores damaged or destroyed; many never reopened, and once-bustling commercial avenues were transformed into empty corridors of shuttered storefronts and broken windows. A vigorous drug trade contributed to the violence of the city, and poverty demoralized the residents. Dangerous and dirty, it provided rich mulch for Lynch’s imagination. “Philadelphia was a terrifying place,” said Jack Fisk, “and it introduced David to a world that was really seedy.”

Situated in the center of the city like a demilitarized zone was the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. “There was a lot of conflict and paranoia in the city, and the school was like an oasis,” recalled Lynch’s classmate Bruce Samuelson.1 Housed in an ornate Victorian building, the Academy, the oldest art school in the country, was regarded as a conservative school during the years Lynch was there, but it was exactly the launching pad he needed.

“David moved in with me in the little room I’d rented,” said Fisk. “He came in November of 1965 and we lived there until he started classes in January. The room had two couches, which we slept on, and I’d collected a bunch of dead plants that were scattered around—David likes dead plants. Then, on New Year’s Day, we rented a house for forty-five dollars a month that was across the street from the morgue in a scary industrial part of Philadelphia. People were afraid to visit us, and when David walked around he carried a stick with nails sticking out of it in case he got attacked. One day a policeman stopped him, and when he saw the stick he said, ‘That’s good, you should keep that.’ We worked all night and slept all day and didn’t interact with the instructors much—all we did was paint.”

Lynch and Fisk didn’t bother going to school too often but quickly fell into a community of like-minded students. “David and Jack showed up kind of like the dynamic duo and became part of our group,” recalled artist Eo Omwake. “We were the fringy, experimental people, and there were about a dozen in our group. It was an intimate circle of people and we encouraged each other and all lived a frugal, bohemian lifestyle.”2

Among the circle was painter Virginia Maitland, who remembered Lynch as “a corny, clean-cut guy who drank a lot of coffee and smoked cigarettes. He was eccentric in how straight he was. He was usually with Jack, who was tall like Abraham Lincoln and was kind of a hippie, and Jack’s dog, Five, was usually with them. They made an interesting pair.”3

“David always wore khakis with Oxford shoes and big fat socks,” said classmate James Havard. “When we met we became friends right off because I liked his excitement about working—if David was doing something he loved, he’d really get into it. Philadelphia was very rough then, though, and we were all just scraping by. We didn’t run around much at night, because it was too dangerous, but we were wild in our own way and David was, too. We’d all be at my place listening to the Beatles, and he’d be beating on a five-pound can of potato chips like it was a drum. He’d just bang on it.”4

Samuelson recalled being struck by “the gentlemanly way David spoke and the fact that he wore a tie—at the time nobody but the faculty wore ties. I remember walking away the first time we met and sensing something was wrong, and when I turned and looked back I saw that he had two ties on. He wasn’t trying to draw attention to himself—the two ties were just part of who he was.”

Five months before Lynch arrived at the Academy, Peggy Lentz Reavey started classes there. The daughter of a successful lawyer, Reavey graduated from high school, went straight to the Academy, and was living in a dorm on campus when she first crossed paths with Lynch. “He definitely caught my eye,” she recalled. “I saw him sitting there in the cafeteria and I thought, That is a beautiful boy. He was kind of at sea at that point and many of his shirts had holes in them, and he looked so sweet and vulnerable. He was exactly the kind of wide-eyed, angelic person a girl wants to take care of.”

Both Reavey and Lynch were involved with other people when they met, so the two were just friends for several months. “We used to eat lunch together and enjoyed talking, but I remember thinking he was a little slow at first because he had no interest in the things I grew up loving and associated with being an artist. I thought artists weren’t supposed to be popular in high school, but here’s this dreamy guy who’d been in a high school fraternity and told wonderful stories about a world I knew nothing about. Class ski trips, shooting rabbits in the desert outside Boise, his grandfather’s wheat ranch—so foreign to me, and funny! Culturally, we came from completely different worlds. I had this cool record of Gregorian chant I played for him, and he was horrified. ‘Peg! I can’t believe you like this! It’s so depressing!’ Actually, David was depressed when we were getting to know each other.”

Omwake concurred: “When David was living near the morgue, I think he went through a depressed period—he was sleeping, like, eighteen hours a day. One time I was at the place he shared with Jack, and Jack and I were talking when David woke up. He came out, drank four or five Cokes, talked a little bit, then went back to bed. He was sleeping a lot during that period.”

When he was awake Lynch must have been highly productive, because he progressed quickly at school. Five months after starting classes he won an honorable mention in a school competition, with a mixed-media sculpture involving a ball bearing that triggered a chain reaction featuring a light bulb and a firecracker. “The Academy was one of the few art schools left that stressed a classical education, but David didn’t spend much time doing first-year classes like still-life drawing,” said Virginia Maitland. “He moved into advanced classes fairly quickly. There were big studios where they put everybody in the advanced category, and there were five or six of us in there together. I remember getting a real charge out of watching David work.”

Lynch was already technically skilled when he arrived at the Academy but hadn’t yet developed the unique voice that informs his mature work, and during his first year he tried on several different styles. There are detailed graphite portraits rendered with a fine hand that are surreal and strange—a man with a bloody nose, another vomiting, another with a cracked skull; figures Lynch has described as “mechanical women,” which combine human anatomy with machine parts; and delicate, sexually charged drawings evocative of work by German artist Hans Bellmer. They’re all executed with great finesse, but Lynch’s potent sensibility isn’t really there yet. Then, in 1967, he produced The Bride, a six-by-six-foot portrait of a spectral figure in a wedding dress. “He was diving headlong into darkness and fear with it,” said Reavey of the painting, which she regards as a breakthrough and whose whereabouts are unknown. “It was beautifully painted, with the white lace of the girl’s dress scumbled against a dark ground, and she’s reaching a skeletal hand under her dress to abort herself. The fetus is barely suggested and it’s not bloody . . . just subtle. It was a great painting.”

Lynch and Fisk continued to live across the street from the morgue until April of 1967, when they relocated to a house at 2429 Aspen Street, in an Irish Catholic neighborhood. They moved into what’s known as a “Father, Son, and Holy Ghost” row house, with three floors; Fisk was on the second, Lynch was on the third, and the bottom floor was the kitchen and living room. Reavey was living in an apartment a bus ride away, and by that point she and Lynch had become a couple. “He made a point of calling it ‘friendship with sex,’ but I was pretty hooked,” recalled Reavey, who became a regular presence on Aspen Street and wound up living there with Lynch and Fisk, until Fisk moved into a loft above a nearby auto-body shop a few months later.

“David and Jack were hilarious together—you laughed around those two constantly,” said Reavey. “David used to ride his bike beside me when we walked home from school, and one day we found an injured bird on the sidewalk. He was very interested in this and took it home, and after it died he spent most of the night boiling it to get the flesh off the bird so he could make something with the skeleton. David and Jack had a black cat named Zero, and the next morning we were sitting drinking coffee, and we heard Zero in the other room crunching the bones to pieces. Jack laughed his head off over that.

“David’s favorite place to eat was a drugstore coffee shop on Cherry Street, and everybody in the place knew us by name,” continued Reavey of her first few months with Lynch. “David would tease the waitresses and he loved Paul, the elderly gentleman at the cash register. Paul had white hair and glasses and wore a tie, and he always talked to David about his television. He talked about shopping for it and what a good one he’d gotten, and he’d always wind up this conversation about his TV by saying, with great solemnity, ‘And, Dave . . . I am blessed with good reception.’ David still talks about Paul and his good reception.”

The core event of the David Lynch creation myth took place early in 1967. While working on a painting depicting a figure standing among foliage rendered in dark shades of green, he sensed what he’s described as “a little wind” and saw a flicker of movement in the painting. Like a gift bestowed on him from the ether, the idea of a moving painting clicked into focus in his mind.

He discussed collaborating on a film with Bruce Samuelson, who was producing visceral, fleshy paintings of the human body at the time, but they wound up scrapping the idea they developed. Lynch was determined to explore the new direction that had presented itself to him, though, and he rented a camera from Photorama, in downtown Philadelphia, and made Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times), a one-minute animation that repeats six times and is projected onto a unique six-by-ten-foot sculpted screen. Made on a budget of two hundred dollars and shot in an empty room in a hotel owned by the Academy, the film pairs three detailed faces cast in plaster, then fiberglass—Lynch cast Fisk’s face twice and Fisk cast Lynch’s face once—with three projected faces. Lynch was experimenting with different materials at the time, and Reavey said, “David had never used polyester resin before Six Men Getting Sick, and the first batch he mixed burst into flames.”

The bodies of all six figures in the piece have minimal articulation and center on swollen red orbs representing stomachs. The animated stomachs fill with colored liquid that rises until the faces erupt with sprays of white paint that trickle down a purple field. The sound of a siren wails throughout the film, the word “sick” flashes across the screen, and hands wave in distress. The piece was awarded the school’s Dr. William S. Biddle Cadwalader Memorial Prize, which Lynch shared with painter Noel Mahaffey. Fellow student H. Barton Wasserman was impressed enough to commission Lynch to create a similar film installation for his home.

“David painted me with bright-red acrylic paint that burned like hell and rigged up this thing with a showerhead,” Reavey recalled of the Wasserman commission. “In the middle of the night he needed a showerhead and length of hose, so he goes out into the alleyway and comes back with them! That kind of thing happened to David a lot.” It took Lynch two months to shoot two minutes and twenty-five seconds of film for the piece, but when he sent it to be processed, he discovered the camera he’d been using was broken and the film was nothing but a long blur. “He put his head in his hands and wept for two minutes,” said Reavey, “then he said, ‘Fuck it,’ and sent the camera to be fixed. He’s very disciplined.” The project was decommissioned, but Wasserman allowed Lynch to keep the remainder of the funds he’d allotted for it.

In August of 1967, Reavey learned she was pregnant, and when the fall semester began a month later, Lynch left the Academy. In a letter to the school administration, he explained, “I won’t be returning in the fall, but I’ll be around from time to time to have some Coca-Cola. I just don’t have enough money these days, and my doctor says I’m allergic to oil paint. I am developing an ulcer and pinworms on top of my spasms of the intestines. I don’t have the energy for continuing my conscientious work here at the Penn. Academy of the Fine Arts. Love—David. P.S.: I am seriously making films instead.”5

At the end of the year Reavey left school, too. “David said, ‘Let’s get married, Peg. We were going to get married anyway. Let’s just get married,’ ” Reavey recalled. “I couldn’t believe I had to go and tell my parents I was pregnant, but we did, and it helped that they adored David.

“We got married on January 7th of 1968 at my parents’ church, which had just gotten a new minister, who was great,” she continued. “He was on our side: Hey, you guys found love, fantastic. I was about six months pregnant at the time and wore a floor-length white dress, and we had a formal ceremony that David and I both found funny. My parents invited their friends and it was awkward for them, so I felt bad about that, but we just rolled with it. We went to my parents’ house afterward for hors d’oeuvres and champagne. All our artist friends came and there was plenty of champagne flowing and it was a wild party. We didn’t go on a honeymoon, but they booked us a room for one night at the Chestnut Hill Hotel, which is beautiful now but was a dump then. We stayed in a dismal room, but we were both happy and had a lot of fun.”

Using the funds remaining from the Wasserman commission, along with financial aid from his father, Lynch embarked on his second movie, The Alphabet. A four-minute film starring Reavey, The Alphabet was inspired by Reavey’s story of her niece giving an anxious recitation of the alphabet in her sleep. Opening with a shot of Reavey in a white nightgown lying on a white-sheeted bed in a black void, the film goes on to intercut live action with animation. The drawings in the film are accompanied by an innovative soundtrack that begins with a group of children chanting “A-B-C,” then segues into a male baritone (Lynch’s friend Robert Chadwick) singing a nonsensical song in stentorian tones; a crying baby and cooing mother; and Reavey reciting the entire alphabet. Described by Lynch as “a nightmare about the fear connected with learning,” it’s a charming film with a menacing undercurrent. It concludes with the woman vomiting blood as she writhes on the bed. “The first time The Alphabet screened in an actual movie theater was at this place called the Band Box,” Reavey recalled. “The film started but the sound was off.” Lynch stood up and shouted, “Stop the film,” then raced up to the projection booth with Reavey behind him. Reavey’s parents had come to see the movie, and Lynch remembers the evening as “a nightmare.”

“David’s work was the center of our life, and as soon as he made a film it was all about him being able to make another one,” said Reavey. “I had no doubt that he loved me, but he said, ‘The work is the main thing and it has to come first.’ That’s just the way it was. I felt extremely involved in David’s work, too—we really did connect in terms of aesthetics. I remember seeing him do stuff that just wowed me. I’d say, ‘Jesus! You’re a genius!’ I said that a lot, and I think he is. He would do stuff that seemed so right and original.”

Reavey had begun working in the bookstore at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1967, and she continued at her job until she went into labor. Jennifer Chambers Lynch arrived on April 7th, 1968, and Reavey recalled, “David got a kick out of Jen but had a hard time with the crying at night. He had no tolerance for that. Sleep was important to David, and waking him up was not fun—he had issues with his stomach and always had an upset stomach in the morning. But Jen was a great, really easy kid and was the center of my life for a long time—the three of us did everything together and we were an idyllic family.”

When Reavey and Lynch married, Reavey’s father gave them two thousand dollars, and Lynch’s parents contributed additional funds that allowed them to purchase a house. “It was at 2416 Poplar, at the corner of Poplar and Ring-gold,” Reavey said. “Bay windows in the bedroom—into which our bed was tucked—looked onto the Ukrainian Catholic church, and there were lots of trees. That house made a lot of things possible, but aspects of it were pretty rough. We ripped up all the linoleum and never finished sanding the wooden floors, and parts of it were really bitten up—if I spilled something in the kitchen, it just soaked into the wood. David’s mother visited us right before we moved to California and said, ‘Peggy, you’re going to miss this floor.’ Sunny had a wonderful, very dry sense of humor. She once looked at me and said, ‘Peggy, we’ve worried about you for years. David’s wife . . .’ She could be funny, and Don had a great sense of humor, too. I always had fun with David’s parents.”

Life as Lynch’s wife was interesting and rich for Reavey; however, the violence of Philadelphia was no small thing. She’d grown up there and felt it wasn’t any rougher than any other large Northeastern city during the 1960s, but she conceded that “I didn’t like it when somebody got shot outside our house. Still, I went out every day and pushed the baby coach all over town to get film or whatever we needed, and I wasn’t afraid. It could be creepy, though.

“One night when David was out I saw a face at a window on the second floor, then after David got home we heard someone jump down. The next day a friend loaned David a shotgun, and we spent the night sitting on our blue velvet couch—which David still pines for—with him gripping this rifle. Another time we were in bed and heard people trying to bash in the front door downstairs, which they succeeded in doing. We had a ceremonial sword under the bed that my father had given us, and David pulled his boxer shorts on backward, grabbed the sword, ran to the top of the stairs, and yelled ‘Get the hell out of here!’ It was a volatile neighborhood, and a lot happened at that house.”

Lynch didn’t have a job when his daughter was born, nor was he looking for one when Rodger LaPelle and Christine McGinnis—graduates of the Academy and early supporters of Lynch’s art—offered him a job making prints in a shop where they produced a successful line of fine-art etchings. McGinnis’s mother, Dorothy, worked at the printshop, too, and LaPelle recalled, “We all had lunch together every day, and the only thing we talked about was art.”6

The strongest paintings Lynch made during his time in Philadelphia were produced during the final two years that he lived there. Lynch had seen and been impressed by an exhibition of work by Francis Bacon, which ran from November through December of 1968 at the Marlborough-Gerson Gallery in New York. He wasn’t alone in his admiration, and Maitland said that “most of us were influenced by Bacon then, and I could see Bacon’s influence on David at the time.” Bacon is inarguably there in the paintings Lynch completed during this period, but his influence is largely subsumed by Lynch’s vision.

As is the case with Bacon’s work, most of Lynch’s early pictures are portraits, and they employ simple vertical and horizontal lines that transform the canvases into proscenium stages, which serve as the setting for curious occurrences. The occurrences in Lynch’s pictures are the figures themselves. Startling creatures that seem to have emerged from loamy soil, they’re impossible conglomerations of human limbs, animal forms, and organic growths that dissolve the boundaries customarily distinguishing one species from the next; they depict all living things as parts of a single energy field. Isolated in black environments, the figures often appear to be traveling through murky terrain that’s freighted with danger. Flying Bird with Cigarette Butts (1968) depicts a figure hovering in a black sky with a kind of offspring tethered to its belly by a pair of cords. In Gardenback (1968–1970), an eagle seems to have been grafted onto human legs. Growths sprout from the rounded back of this figure, which walks in profile and has a breastlike mound erupting from the base of the spine.

It was during the late 1960s that Lynch made these visionary paintings, and although the latest Beatles album was usually on permanent rotation on the turntable at home, the deeper waters of the counterculture were of little interest to him. “David never did drugs—he didn’t need them,” Reavey recalled. “A friend once gave us a lump of hash and told us we should smoke it and then have sex. We didn’t know what we were doing, so we smoked all of it, sitting there on the blue velvet couch, and we could barely crawl upstairs by the time we were done. Drinking was never a huge thing in our lives, either. My dad used to make this thing he called ‘the Lynch Special’ out of vodka and bitter lemon that David liked, but that was about the extent of his drinking.”

“I never saw David intoxicated other than at my wedding, where everybody was falling-down drunk,” said Maitland. “Later, I remember my mother saying, ‘Your friend David was jumping up and down on my nice yellow couch!’ It’s probably the only time David’s been that drunk.”

With encouragement from Bushnell Keeler, Lynch applied for a $7,500 grant from the American Film Institute in Los Angeles and submitted The Alphabet, along with a new script he’d written called The Grandmother, as part of his application. He received $5,000 to make The Grandmother, the story of a lonely boy who’s repeatedly punished by his cruel parents for wetting the bed. A thirty-four-minute chronicle of the boy’s successful attempt to plant and grow a loving grandmother, the film starred Lynch’s co-worker Dorothy McGinnis as the grandmother. Richard White, a child from Lynch’s neighborhood, played the boy, and Robert Chadwick and Virginia Maitland played the parents.

Lynch and Reavey transformed the third floor of their house into a film set, and Reavey recalled “trying to figure out how to paint the room black and still define the shape of a room; we ended up using chalk at the joints where the ceiling meets the wall.” The creation of the set also called for the elimination of several walls, and “That left a big mess,” she said. “I spent lots of time filling little plastic bags with plaster and putting them in the street to be picked up. Big bags would’ve been too heavy, so we used little bags that had ties on them like bunny ears. One day we were looking out the window when the trash guys came, and David was falling down laughing because we’d filled the street with these little bags and it looked like a huge flock of rabbits.”

Maitland said that her participation in The Grandmother began with an overture from Reavey. “Peggy said, ‘Do you want to do this? He’ll pay you three hundred dollars.’ I have strong memories of being in their house and how bleak it was the way he had it set up. David had us put rubber bands around our faces to make us look strange and made all of our faces up with white. There’s a scene where Bob and I are in the ground buried up to the neck, and he needed a place where he could dig deep holes, so we shot that scene at Eo Omwake’s parents’ house in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. David dug the holes, which we got into, then he covered us up with dirt, and I remember being in the ground for what seemed like way too long. But that’s the thing about David that makes him so great—he was an incredible director, even then. He could get you to do anything, and he’d do it in the nicest way.”

A crucial element of The Grandmother fell into place when Lynch met Alan Splet, a kind of freelance genius of sound. “David and Al getting together was a cool thing—they just really clicked,” said Reavey. “Al was an eccentric, sweet guy who’d been an accountant for Schmidt’s Brewery, and he was just naturally gifted with sound. He had the red beard, red hair, and intense eyes of Vincent van Gogh and was skinny as a pencil and blind as a bat, so he couldn’t drive and had to walk everywhere, which was fine with him. He was a totally uncool dresser who always wore these cheap short-sleeved shirts and was a wonderful cellist. When he was living with us in L.A., we’d sometimes come home and he’d be blasting classical music on the record player and sitting there conducting.”

Lynch discovered that existing libraries of sound effects were inadequate for the needs of The Grandmother, so he and Splet produced their own effects and created an unconventional soundtrack that’s vital to the film. The Grandmother was almost completed in 1969 when the director of the American Film Institute, Toni Vellani, took a train from Washington, D.C., to Philadelphia for a screening; he was excited by the film and vowed to see to it that Lynch was invited to be a fellow at the AFI’s Center for Advanced Film Studies for the fall semester of 1970. “I remember David had a brochure from the AFI and he used to just sit and stare at it,” Reavey recalled.

Vellani kept his word, and in a letter to his parents dated November 20th, 1969, Lynch said, “We feel that a miracle has occurred for us. I will probably spend the next month trying to get used to the idea of being so lucky, and then after Christmas Peggy and I will ‘roll ’em’ as they say in the trade.”

Philadelphia had worked its strange magic and exposed Lynch to things he hadn’t previously been familiar with. Random violence, racial prejudice, the bizarre behavior that often goes hand in hand with deprivation—he’d seen these things in the streets of the city and they’d altered his fundamental worldview. The chaos of Philadelphia was in direct opposition to the abundance and optimism of the world he’d grown up in, and reconciling these two extremes was to become one of the enduring themes of his art.

The ground had been prepared for the agony and the ecstasy of Eraserhead, and Lynch headed for Los Angeles, where he’d find the conditions that would allow the film to take root and grow. “We sold the house for eight thousand dollars when we left,” said Reavey. “We get together now and talk about that house and that blue couch we bought at the Goodwill—David gets so excited talking about the stuff we got at the Goodwill. He’ll say, ‘That couch was twenty dollars!’ For some reason Jack was in jail the day before we left Philadelphia, so he couldn’t help us move it. David still says, ‘Damn it! We should’ve brought that couch with us!’ ”

I KNEW NOTHING ABOUT politics or the conditions in Philadelphia before I went there. It’s not that I didn’t care—I just didn’t know, because I wasn’t into politics. I don’t think I even voted in those days. So I got accepted at the Academy and I got on a bus and went up there, and it was fate that I wound up at that school. Jack and I didn’t go to classes—the only reason we were in school was to find like-minded souls, and we found some, and we inspired each other. All the students I hung out with were serious painters, and they were a great bunch. Boston was a bad bunch. They just weren’t serious.

My parents supported me as long as I was in school, and my dear dad never disowned me, but there’s some truth to Peggy and Eo Omwake saying I was a little depressed when I first got to Philadelphia. It wasn’t exactly depression—it was more like a melancholy, and it didn’t have anything to do with the city. It was like being lost. I hadn’t found my way yet and maybe I was worried about it.

I went there at the end of 1965 and stayed with Jack in his little room. When I got there Jack had a puppy named Five, so there was newspaper all over the floors because he was housebreaking him. When you walked around the place there was the sound of rustling newspaper. Five was a great dog and Jack had him for many years. Next door to us was the Famous Diner, which was run by Pete and Mom. Pete was a big guy and Mom was a big gal who had weird yellow hair. She looked like the picture of the woman on the bags of flour—you know, the blue-apron waitress thing. The Famous Diner was a train-car diner, and it had a long counter and booths along the wall and it was so fantastic. They’d deliver the jelly donuts at five-thirty in the morning.

Jack’s place was small so we needed to move, and we found a place at 13th and Wood. We moved on New Year’s Eve and I remember moving like it was yesterday. It was around one in the morning and we moved with a shopping cart. We had Jack’s mattress and all his stuff in there, and I just had one bag of stuff, and we were pushing the cart along and we passed this happy couple, drunk probably, and they said, “You’re moving on New Year’s Eve? Do you need any money?” I yelled back, “No, we’re rich!” I don’t know why I said that, but I felt rich.

Our place was like a storefront, and in the back was a toilet and washbasin. There was no shower or hot water, but Jack rigged up this stainless-steel coffee maker that would heat up water and he had the whole first floor, I had a studio on the second floor next to this guy Richard Childers, who had a back room on the second floor, and I had a bedroom in the attic. The window in my bedroom was blown out so I had a piece of plywood sitting in there, and I had a cooking pot I’d pee in then empty out into the backyard. There were lots of cracks in my bedroom walls, so I went to a phone booth and ripped out all the white pages—I didn’t want the yellow pages, I wanted the white pages. I mixed up wheat paste and papered the entire room with the white pages, and it looked really beautiful. I had an electric heater in there, and one morning James Havard came to wake me up and give me a ride to school and the plywood had blown out of the window, so there was a mound of fresh snow on the floor in my room. My pillow was almost on fire because I had the heater close to my bed, so he maybe saved my life.

James was the real deal. He was older and he was a great artist and he worked constantly. You know the word “painterly”? This guy was painterly. Everything he touched had this fantastic, organic painterly thing, and James had a lot of success. Six or seven of us went to New York once because James was in a big show way uptown. By the end of the opening we were all drunk and we had to go way downtown, and I don’t know if I was driving, but I remember this as if I was driving. It was one or two in the morning and we hit every single green light from way uptown all the way to the bottom of the city. It was incredible.

Virginia Maitland turned out to be a serious painter, but I sort of remember her as a party girl. She was out in the street one day and there was a young man whistling bird calls on the corner. She took him home and he did bird calls in her living room and she liked that so she kept him, and that was Bob Chadwick. Bob was a machinist and his boss loved him—Bob could do no wrong. He worked at this place that had a thirty-five-foot lathe with ten thousand different gears to do complicated cuttings, and Bob was the only one who could run it. He just intuitively knew how to do things. He wasn’t an artist, but he was an artist with machines.

Our neighborhood was pretty weird. We lived next door to Pop’s Diner, which was run by Pop and his son Andy, and I met a guy at Pop’s who worked in the morgue, and he said, “Anytime you want to visit, just let me know and ring the doorbell at midnight.” So one night I went over there and rang the bell and he opened the door, and the front was like a little lobby. It had a cigarette machine, a candy machine, old forties tile on the floor, a little reception area, a couch, and this corridor that led to a door into the back. He opened that door and said, “Go on in there and make yourself at home,” and there was nobody working back there, so I was alone. They had different rooms with different things in them, and I went into the cold room. It was cold because they needed to preserve the bodies, and they were in there stacked up on these bunk-bed-type shelves. They’d all been in some kind of accident or experienced some violence, and they had injuries and cuts—not bleeding cuts, but they were open wounds. I spent a long time in there, and I thought about each one of them and what they must’ve experienced. I wasn’t disturbed. I was just interested. There was a parts room where there were pieces of people and babies, but there wasn’t anything that frightened me.

One day on the way to the White Tower to get lunch, I saw the smiling bags of death at the morgue. When you walked down this alley you’d see the back of the morgue opened up, and there were these rubber body bags hanging on pegs. They’d hose them out and water and body fluids would drip out, and they sagged in the middle so they were like big smiles. Smiling bags of death.

I must’ve changed and gotten kind of dirty during that period. Judy Westerman was at the University of Pennsylvania then and I think she was in a sorority, and one time Jack and I got a job driving some paintings up there. I thought, Great, I can see Judy. So we go up there and deliver this stuff, then I go to her dormitory and walk in and this place was so clean, and I was in art school being a bum, and all the girls are giving me weird looks. They sent word to Judy that I was there, and I think I embarrassed her. I think they were saying “Who the hell is that bum over there?” But she came down and we had a really nice talk. She was used to that part of me, but they weren’t. That was the last time I ever saw Judy.

We once had a big party at 13th and Wood. The party’s going on and there’s a few hundred people in the house, and somebody comes up to me and says, “David, so-and-so’s got a gun. We gotta get it from him and hide it.” This guy was pissed off at somebody, so we got his gun and hid it in the toilet—I grew up with guns, so I’m comfortable around them. There were lots of art students at this party, but everybody wasn’t an art student, and there was one girl who seemed a little bit simple, but she was totally sexy. A beautiful combo. It must’ve been winter, because everybody’s coats were on my bed in the attic, so when somebody was leaving I’d go up and get their coat. One time I go to my room and there on my bed, against a kind of mink coat, is this girl with her pants pulled down, and she’d obviously been taken advantage of by someone. She was totally drunk and I helped her up and got her dressed, so that was going on at this party, too.

It was pretty packed and then the cops show up and say, “There’s been a complaint; everybody’s got to go home.” Fine, most everybody left, and there were maybe fifteen people still hanging around. One guy was quietly playing acoustic guitar, it was real mellow, and the cops come back and say, “We thought we told you all to leave.” Just then this girl named Olivia, who was probably drunk, walks up to one of the cops and gives him the finger and says, “Why don’t you go fuck yourself.” “Okay, everybody in the paddy wagon,” and there was one parked out front and everybody got in—me, Jack, Olivia, and these other people—and they drive us to the police station. In interrogation they find out that Jack and I are the ones who live at the house, so we’re arrested as proprietors of a disorderly house and put in jail. Olivia was the one who mouthed off, so she goes to the women’s jail. Jack and I get put in a cell and there are two transvestites—one named Cookie in our cell, and another one down the way—and they talked to each other all night. There was a murderer—he had the cot—and at least six other people in the cell. The next morning we go before the judge and a bunch of art students came and bailed us out.

We got to Philadelphia just before hippies and pigs and stuff like this, and cops weren’t against us at first, even though we looked strange. But it got bad during the time we were there because of the way things were going in the country. Richard had a truck, and one night I went with him to a movie. When we were driving home Richard looked in the rearview mirror and there was a cop behind us. We were approaching an intersection and when the light turned yellow Richard stopped, which I guess tipped off the cops that we were nervous. So the light turns green and we go through the intersection and the sirens and the lights go on. “Pull over!” Richard pulls over to this wide sidewalk next to a high rock wall. This cop walks around to the front of our car and he’s standing in the headlights and he puts his hand on his gun and says, “Get out of the truck!” We get out of the truck. He says, “Hands against the wall!” We put our hands against the wall. They start frisking Richard, and I thought, They’re frisking Richard, not me, so I lowered my arms and immediately this hand slammed me into the wall. “Hands against the wall!” Now there’s a paddy wagon and like twenty cops, and they put us in the paddy wagon and we’re riding along in this metal cage. We hear somebody talking over the cop radio describing two guys and what they’re wearing, and Richard and I look at each other and realize we look exactly like the guys being described. We get down to the station and in comes this old man holding a bloody bandage to his head, and they bring him over to us and he looks at us, then says, “No, these aren’t the guys,” and they let us go. That made me really nervous.

I’m quoted saying that I like the look of figures in a garden at night, but I don’t really like gardens except for a certain kind. I once did a drawing of a garden with electrical motors in it that would pump oil, and that’s what I like—I like man and nature together. That’s why I love old factories. Gears and oil, all that mechanical engineering, great big giant clanging furnaces pouring molten metal, fire and coal and smokestacks, castings and grinding, all the textures and the sounds—it’s a thing that’s just gone, and everything’s quiet and clean now. A whole kind of life disappeared, and that was one of the parts of Philadelphia that I loved. I liked the way the rooms were in Philadelphia, too, the dark wood, and rooms with a certain kind of proportions, and this certain color of green. It was kind of a puke green with a little white in it, and this color was used a lot in poor areas. It’s a color that feels old.

I don’t know if I even had an idea when I started Six Men Getting Sick—I just started working. I called around and found this place called Photorama, where 16mm cameras were way cheaper than other places. It was kind of sleazy, but I went and rented this Bell and Howell windup camera that had three lenses on it, and it was a beautiful little camera. I shot the film in this old hotel the Academy owned, and the rooms there were empty and gutted, but the hallways were filled with rolled-up Oriental carpets and brass lamps and beautiful couches and chairs. I built this thing with a board, like a canvas, propped on top of a radiator, then I put the camera across the room on top of a dresser that I found in the hallway and moved into the room. I nailed the dresser to the floor to make sure the camera didn’t move at all.

I have no idea what gave me the idea to do the sculpture screen. I don’t think the plastic resin burst into flame when I mixed it, but it did get so hot it steamed like crazy. You mixed this stuff in these paper containers, and I loved mixing it hot. The paper would turn brown and scorch and it would heat so much that you’d hear it crackling and you’d see these gases just steaming out of this thing. When the film was done I built this kind of erector-set structure to take the film up to the ceiling and back down through the projector, and I had a tape recorder with a siren on a loop that I set on the stage. It was in a painting and sculpture show, and the students let me turn the lights off for fifteen minutes out of every hour, and that’s pretty damn good.

Bart Wasserman was a former Academy student whose parents died and left him a lot of money, and when he saw Six Men Getting Sick he told me he wanted to give me a thousand dollars to make a film installation for his house. I spent two months working on this film for Bart, but when it was developed it was nothing but a blur. Everybody said I was really upset when that film didn’t come out, so I probably was, but almost immediately I started getting ideas for animation and live action. I thought, This is an opportunity and there’s some reason this is happening, and maybe Bart will let me make that kind of film. I called Bart and he said, “David, I’m happy for you to do that; just give me a print.” I later met Bart’s wife in Burgundy, France—she moved over there—and she told me Bart never did an altruistic thing in his life except for the thing he did for me. That film not coming out ended up being a great doorway to the next thing. It couldn’t have been better. I never would’ve gotten a grant from AFI if that hadn’t happened.

The film I made with the rest of Bart’s money, The Alphabet, is partly about this business of school and learning, which is done in such a way that it’s kind of a hell. When I first thought of making a film, I heard a wind and then I saw something move, and the sound of the wind was just as important as the moving image—it had to be sound and picture moving together in time. I needed to record a bunch of sounds for The Alphabet, so I went to this lab, Calvin de Frenes, and rented this Uher tape recorder. It’s a German tape recorder, a real good recorder. I recorded a bunch of stuff then realized that it was broken and was distorting these sounds—and I was loving it! It was incredible. I took it back and told them it was broken, so I got it for free, and I got all these great sounds, too. Then I took everything into Bob Column at Calvin de Frenes, and he had a little four-track mixing console and I mixed it there with Bob. This mixing and getting stuff in sync was magical.

Before I got together with Peggy, I’d have brief relationships with people then move on. I dated a girl named Lorraine for a while, and she was an art student who lived with her mother in the suburbs of Philadelphia. Lorraine looked Italian and she was a fun girl. We’d be at her mom’s house and all three of us would go down to the basement and open up the freezer and pick out a TV dinner. This freezer was packed with all different kinds of TV dinners, and her mom would heat ’em up for us. You just put them in the oven and pretty soon you’ve got a dinner! And they were good! Lorraine and her mom were fun. Lorraine ended up marrying Doug Randall, who took some still photos for me on The Grandmother. There was also this girl Margo for a while, and a girl named Sheila, and I really liked Olivia, the girl who got arrested, but she wasn’t really my girlfriend. There’s a film called Jules and Jim, and Olivia and Jack and I were kind of like that—we’d go places together.

Peggy was the first person I fell in love with. I loved Judy Westerman and Nancy Briggs, but they didn’t have a clue about what I did at the studio and were destined to live a different kind of life. Peggy knew everything and appreciated everything and she was my number-one fan. I didn’t know how to type and Peggy typed my scripts, and she was incredible to me, so incredible. We started out being friends and we’d sit and talk at the drugstore next to the Academy and it was great.

One day Peggy told me she was pregnant, and one thing led to another and we got married. The only thing I remember about our wedding is that Jack wore a taxicab-driver shirt to it. I loved Peggy but I don’t know that we would’ve gotten married if she hadn’t been pregnant, because marriage doesn’t fit into the art life. You’d never know I think that, though, because I’ve been married four times. Anyhow, a few months later Jennifer was born. When Jen was born fathers were never in the delivery room, and when I asked if I could go in, the guy looked at me funny. He said, “I’ll watch you and see how you do,” so he took blood from Peggy and I didn’t pass out, and she puked up a bunch of stuff and that didn’t bother me, so he said, “You’re good to come in.” So I scrubbed up and in I went. It was good. I wanted to see it just to see. Having a child didn’t make me think, Okay, now I’ve got to settle down and be serious. It was like . . . not like having a dog, but it was like having another kind of texture in the house. And babies need things and there were things I could contribute. We heard that babies like to see moving objects, so I took a matchbook and bent all the matches in different directions and hung it from a thread, and I’d dangle this thing in front of Jen’s face and spin it, like a poor man’s mobile. I think it boosted her IQ, because Jen’s so smart!

I always felt that the work was the main thing, but there are fathers now who love spending time with their children and go to school functions and all that. That wasn’t my generation. My father and mother never went to our baseball games. Are you kidding me? That was our thing! What are they going to go for? They’re supposed to be working and doing their thing. This is our thing. Now all the parents are there, cheering their kids on. It’s just ridiculous.

Not long before Jen was born, Peggy said, “You gotta go and see Phyllis and Clayton’s house. They’ve got a setup that’s unbelievable.” So I rode my bike over to see this artist couple we knew and they were living in this huge house. Both of them were painters and each of them had their own floor to work in, and they showed me around and I said, “You guys are so lucky—this is great.” Phyllis said, “The house next door is for sale,” so I went and looked at this place and it was a corner house that was even bigger than their house. There was a sign with the name of the real estate company, so I rode over to Osakow Realty and introduced myself to this nice plump lady in a little office and she said, “How can I help you?” I said, “How much is that house at 2416 Poplar?” and she said, “Well, David, let’s take a look.” She opened up the book and said, “That house is twelve rooms, three stories, two sets of bay windows, fireplaces, earthen basement, oil heat, backyard, and tree. That house is three thousand, five hundred dollars, six hundred dollars down.” I said, “I’m buying that house,” and we did. It was right on the borderline between this Ukrainian neighborhood and a black neighborhood, and there was big, big violence in the air, but it was the perfect place to make The Grandmother and I was so lucky to get it. Peggy and I loved that house. Before we bought the place it had been a communist meeting house, and I found all kinds of communist newspapers under the linoleum flooring. The house had kind of a softwood floor, and they’d put newspaper down then put linoleum on top of the newspaper. This linoleum was really old, so I was breaking it up and throwing it away and one day I was working at the front of the house and I hear this noise like the sound of many waters. It was weird, something really unusual. I opened the blinds and looked out and there were ten thousand marchers coming down the street, and it freaked me out. That was the day Martin Luther King was killed.

We didn’t go to the movies a lot. Sometimes I would go to the Band Box, which was the art house where I saw French new wave and all that for the first time, but I didn’t go there much. And even if I was in the middle of making a film, I wasn’t ever thinking I’m in that world. Not in a million years! My friend Charlie Williams was a poet, and when he saw The Alphabet, I said to Charlie, “Is this an art film?” He said, “Yes, David.” I didn’t know anything. I did love Bonnie and Clyde, although that’s not why I started wearing an open-road Stetson panama-style hat. I started wearing one just because I found one at the Goodwill. When you take those hats off you sort of pinch the front of the brim, so they start coming apart. The Stetsons I was buying were already old, so the straw would break and pretty soon there would be a hole there. There are lots of pictures of me in hats with holes in them. I had two or three of them and I loved them.

The Goodwill in Philadelphia was incredible. Okay, I need some shirts, right? I go down Girard Avenue to Broad Street and there’s the Goodwill and they’ve got racks of shirts. Clean. Pressed. Some even starched! Mint. Like brand-new! I’d pick out three shirts, take them up to the counter: How much is this? Three dimes. I was into medical lamps, and this Goodwill had lamps that had all kinds of adjustments and different things, and I had fifteen medical lamps in our living room. I left them in Philadelphia because Jack was supposed to help pack the truck I drove out to Los Angeles, but he worked in a porno place that was busted and he was in jail the day we were loading the truck. It was just my brother and Peggy and me loading, and some good stuff got left behind.

When I got with Peggy, Jack moved into this place over an auto-body shop owned by a guy from Trinidad named Barker, and everybody loved Barker. He had legs like rubber and could crouch and then spring up, and he was built for auto-body work. One day he walked me past all these cars on racks to the very back of the place, where there was this old dusty tarp covering something. He pulls this tarp back and said, “I want you to have this car. This is a 1966 Volkswagen with hardly any miles on it. It was rear-ended and totaled, but I can fix this car and you can have it for six hundred dollars.” I said, “Barker, that is great!” So he fixed it up and it was like brand-new—it even smelled new! It rode so solid and smooth and it was a dream car in mint condition. I loved that car. When I brushed my teeth in the second-floor bathroom, I’d look out the window and see it down there parked in the street and it was so beautiful. So I’m brushing my teeth one morning and I look out and I think, Where did I park my car? It’s not there. That was my first car and it was stolen. So I moved on to my second car. There was a service station at the end of the street where Peggy’s family lived, and Peggy’s father took me down there and said to the guy who ran the place, “David needs a car. What used cars do you have?” I got this Ford Falcon station wagon and it was a dream, too. It was three-on-the-tree, the plainest Ford Falcon station wagon there could be—it had a heater and a radio and nothing else, but it had snow tires on the back and it could go anywhere. I sort of fell in love with that car.

I had to wait for the license plate for the Ford Falcon to come in the mail, so I decided to make one for the meantime. The license plate was a really fun project. I cut some cardboard, and it was a good piece of cardboard that was the same thickness as a license plate. I cut it in exactly the shape of a real license, then went to a car and measured the height of the letters and numbers, and looked at the colors, and made a Day-Glo registration sticker. The problem was that the license I copied had either all letters or all numbers, and my license had letters and numbers, and I later learned that letters and numbers aren’t the same height. So this rookie cop spots my license as a fake because everything was the same height, and this cop was a hero at the precinct for spotting this thing. So cops came to the door and Peggy was crying—it was serious! They came back later and wanted the license plate for the police museum. It was a fuckin’ beautiful job! That was the first time a museum acquired my work.

One night I came home from a movie and went up to the second floor and started to tell Peggy about it, and her eyes are like saucers because someone is outside the bay window. So I go downstairs where our phone is, and our next-door neighbor Phyllis calls right then. She’s a character and she’s talking away until I interrupt her and say, “Phyllis, I’ve gotta hang up and call the police. Somebody was trying to break in.” While I’m on the phone with her I see a pipe move, then I hear breaking glass, and I see someone outside the window and realize someone was in the basement, too—so there were two people. I don’t remember sitting on the couch the next night with a gun like Peggy said—I don’t think we ever had a gun at that place. But, yeah, these sorts of things happened there. Another time I’m sound asleep and I’m woken by Peggy’s face like two inches from mine. “David! There’s somebody in the house!” I get up and put my underpants on backward and reach under the bed and get this ceremonial sword Peggy’s father gave us, and I go to the head of the stairs and yell, “Get the hell out of here!” There were two black couples standing down there and they’re looking at me like I’m totally fucking crazy, right? They’d come in to make love or party or something because they thought it was an abandoned house. They said, “You don’t live here,” and I said, “The hell I don’t!”

By the time Jen was born I’d left school and I wrote that bullshit letter to the administration. Then I got a job. Christine McGinnis and Rodger LaPelle were both painters, but to make money Christine would knock out these animal engravings, and she had her mother, Dorothy, who was known as Flash, in there printing. It was the perfect job for me. Flash and I worked next to each other and there would be a little TV in front of us, and behind us were a hand press and some sinks. You’d start by inking the plate, then you’d take one of these used nylon socks Rodger would get and you’d fold it in a certain way, then you’d dance this nylon over the plate, hitting the mountains and leaving the valleys. Then you’d run a print on real good paper. While I was working in the shop, Rodger told me, “David, I’ll pay you twenty-five dollars to paint on the weekends and I’ll keep the paintings you make.” After I moved to L.A. he would send me paper and pencils to do drawings for him, still paying me. Rodger was and is a friend to artists.

One afternoon I found a used Bolex with a beautiful leather case for four hundred fifty dollars that I wanted to buy at Photorama, but they said, “David, we can’t put a hold on this camera. If someone comes in and wants it, we have to sell it. If you’re here tomorrow morning with the money and it’s still here, you can have it.” I panicked because I didn’t want anybody else to get this thing. I couldn’t wake up in the morning in those days, so Jack and his girlfriend, Wendy, and I took amphetamines and stayed up all night, and I was at the store when they opened. I got the camera.

I did some great drawings on amphetamines. In those days girls were going to doctors and getting diet pills, and it’s like they were giving out scoopfuls of these pills. They’d come home from the doctor with big bags of pills! I wasn’t anti-drug. Drugs just weren’t important to me. One time Jack and I were going to go up to Timothy Leary’s farm at Millbrook and drop acid and stay up there, but that turned out to be a pipe dream that lasted just a couple of days. We didn’t go to the concert at Woodstock, but we did go to Woodstock. It was in the winter and we went up there because we’d heard about this hermit who lived there, and I wanted to see this hermit. Nobody could ever see him. He built this kind of mound place out of earth and rocks and twigs with little streamers on them, and when we went there it was covered with snow. He lived in there, and I think he had places he could peek out to see if someone was coming near him, but you couldn’t see him. We didn’t see him, but we felt him being there.

I don’t know where the idea for The Grandmother came from. There’s a scene where Virginia Maitland and Bob Chadwick come up out of holes in the ground, and I can’t explain why I wanted them to come up out of the earth—it just had to be that way. It wasn’t supposed to look real but it had to be a certain way, and I dug these holes and they got in them. When the scene opens you just see leaves and bushes, then all of a sudden out come these people. Bob and Ginger did great. They weren’t really buried in there, and mostly they had to struggle out of leaves. Then Richard White comes out of his own hole and the two of them bark at him, and there are distorted close-ups of barking. I was doing some sort of stop motion, but I couldn’t tell you how I did it. It was poor man’s stuff but it worked for me. I always say that filmmaking is just common sense. Once you figure out how you want it to look, you kind of know how to do it. Peggy said things went my way when I was making those films, and that’s sort of true. I could just find stuff. I’d just get it.

When it came time to do the sound for The Grandmother, I went and knocked on the sound department door at Calvin de Frenes and Bob opens the door and he says, “David, we have so much work that I had to hire an assistant, and you’ll be working with my assistant, Alan Splet.” My heart kind of dropped and I look over and see this guy—pale, skinny as a rail, old shiny black suit—and Al comes up wearing Coke-bottle glasses and smiles and shakes my hand, and I feel the bones in his arm rattle. That’s Al. I tell him I need a bunch of sounds, so he played me some sound-effects records and said, “Something like this?” I said no. He plays another track and he says, “Maybe this?” I said no. This goes on for a while, then he said, “David, I think we’re going to have to make these sounds for you,” and we spent sixty-three days, nine hours a day, making sounds. Like, the grandmother whistles, right? They hardly had any equipment at Calvin de Frenes and they didn’t have a reverb unit. So Al got an air-conditioning duct that was thirty or forty feet long. We went to a place where I whistled into this duct and Al put a recorder at the other end. Because of the hollowness of the duct, that whistle was a little bit longer by the time it reached the other end. Then he’d play the recording through a speaker into the duct and record it again, and now the reverb is twice as long. We did that over and over until the reverb sounded right. We made every single sound and it was so much fun I cannot tell you. Then I mixed the thing at Calvin de Frenes, and Bob Column very seriously said, “David, number one, you can’t take the film out of here until you pay your bill. Number two, if they charge an hourly rate your bill is going to be staggering. If they charge a ten-minute reel rate, it’s going to be an incredibly good deal for you.” He talked to the people he worked for and I got the ten-minute reel rate.

You had to submit a budget to the AFI to get a grant, and I wrote that my film would cost $7,119, and it ended up costing $7,200. I don’t know how I did that, but I did. The original grant was for $5,000 but I needed $2,200 more to get the film out of Calvin, so Toni Vellani took the train from Washington, D.C. I picked him up at the train station and showed him the film and he said, “You got your money.” While I was driving him back to the train station he said, “David, I think you should come to the Center for Advanced Film Studies in Los Angeles, California.” That’s like telling somebody, You have just won five hundred trillion dollars! Or even greater than that! It’s like telling somebody, You’re going to live forever!