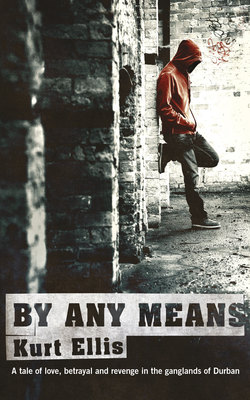

Читать книгу By any means - Kurt Ellis - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6

ОглавлениеThe sun was furious and it poured its anger out upon the earth. The air was thick with heat and humidity. This sticky soup was filled with the clamour of loud voices from the pupils of Bechet Secondary School, enjoying their fifteen-minute break between classes. The school itself was made up of a single brick building and a number of cardboard prefabs that were like ovens in summer and refrigerators in winter. These classrooms were occupied by the lower grades: the reward for getting to Grade 10 was to move into the brick-built main building. Captain joked that the history books at the school were so old that they read, “Ten years ago, when Jan van Riebeeck landed at the Cape …”

Captain liked making jokes about his school, but deep down he loved this old place. And he respected the teachers here greatly. It couldn’t be an easy job, teaching this rowdy bunch, many of them involved in gangs or drugs. Many of them not believing they were good for anything except becoming a taxi driver, boilermaker, welder or some other artisan, if they were lucky. So if they were not going to be more than call-centre agents, why should they bother with studying trigonometry, or biology, or literature? And yet these teachers were still trying to mould these young minds that were already flaking and hardening in the heat of this community. A tough job. A thankless job, most of the time, but a job they did with passion.

The corridor was quiet. Captain raised his knuckles to the door and knocked twice.

“Enter, if your nose is clean.”

Captain smiled as he pushed the door open.

“Anthony,” Mr Williams said, hunched over his work table. “What did you do wrong this time?” The woodwork teacher was a slight man with dark skin and thinning hair.

Captain smiled. “Me, sir? We both know I’m an angel.”

“An angel of disaster,” Mr Williams said, wiping wood dust from his hands and onto his green plastic apron. “What can I do for you?”

“Sir, it’s almost time for the final matric exams and the desks are –”

Mr Williams did not let Captain finish. “Tell me something I don’t know. I know most of the desks are broken and there isn’t enough for all of you. That’s why I’m staying behind after school to make our own desks. We can’t wait for the Department of Education to pull their finger out and come to the party.”

“That’s why I’m here, sir. I’d like to donate some money for the materials you need.”

“Really?” Mr Williams raised a questioning eyebrow.

“Yes, sir. How much money do you need?”

Mr Williams looked through the mist of wood particles that always hung in the air in the woodwork room. At the tools that were neatly hanging on the walls. At the model boats, spice racks and bird houses that students, past and present, had built within these walls.

“Thank you, Anthony,” he said. “But I’m sorry, I can’t accept your money.”

Captain was dumbfounded. “Why not?”

“Because we both know where it comes from.”

“Does it matter?” Captain asked. “I mean, who cares where it comes from. All that’s important is where it’s going.”

Mr Williams untied his apron and hung it on a nail in the wall. “You are smart enough to know that is bullshit, Anthony. It’s the principle. I can’t accept the money you make from doing what you do. And that’s final.”

Captain felt hurt, and then he felt anger rising out of that hurt. But he fought it. With a shrug he said, “I was only trying to help.”

He turned and began to walk out of the room, but Mr Williams called to him, “If you and your boys want to help, come by after school and help me make the desks. I will accept any offer of manual labour.”

Captain turned. “You do remember that you gave me a D in woodwork, sir? I’ll start making a desk and end up making a toothpick.”

Mr Williams smiled. “You weren’t that bad. And you got a D because you kept bunking. I’ll see you and your boys after the final bell.”

Captain smiled and nodded. “Yes, sir.”