Читать книгу Building the Ivory Tower - LaDale C. Winling - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 The City Limits

The evening of May 27, 1923, an oil driller’s bit passed the depth of three thousand feet after nearly two years of drilling into arid West Texas land near Odessa. Gas bubbled up into the Santa Rita well, named for the patron saint of impossible causes, and the drillers stopped their rig, realizing they had found oil where investors had been searching since 1919. The drillers hurried to lease more lands nearby before the news broke. The next morning, crude oil erupted from the well and sprayed over the top of the derrick: the drillers’ bet paid off. Oil honeycombed the land, and the strike instantly made the acreage, which belonged to the University of Texas (UT), worth hundreds, even thousands of times more than when the school leased it as ranching land.1

Federal policy and new technology made crude oil an essential commodity in the American economy. Transportation policy shifted early in the twentieth century from emphasizing rail to automobility. Gasoline-powered internal combustion engines moved goods and people from farm to market, from city to city, and from producer to port. American oil consumption increased steadily throughout most of the twentieth century, and the University of Texas sat on a large pile of royalties that grew larger every year.2

That wealth held the potential to lift the University of Texas, and the city of Austin with it, to a new elite rank. However, its Southern, segregationist practices and its national aspirations were in conflict. In the midcentury decades, the university’s northern peers increasingly looked askance at Jim Crow segregation, and national policy chipped away at it until, by the mid-1950s, explicit segregation was no longer viable policy for either a great university or a major city.

Discussions of segregation and the influence of the civil rights movement on higher education often center on legal battles and flash points like the one that erupted over James Meredith’s enrollment at the University of Mississippi in 1962: famous clashes over enrollment decided in favor of integration.3 George Wallace’s 1963 symbolic blockade of the door of the University of Alabama promised “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” and propelled him to national prominence as a part of the “massive resistance” movement.

Urban development, however, was also a key mechanism of racial segregation—a “passive resistance” counterpart. Robust suburbs at the metropolitan periphery of cities like Atlanta and Detroit were often populated by and usually limited to white, middle-class professionals.4 Universities helped drive this suburban growth at midcentury. On the outskirts of Chicago, the University of Chicago helped build and manage a national research laboratory in DuPage County after World War II that led to growth in the nearby suburbs of Naperville and Downers Grove. Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, created a research park that was central to the development of Silicon Valley far outside the largest Bay Area cities of San Francisco and Oakland.5 The state of New York incorporated the University of Buffalo into its state higher-education system and created a new, second campus in suburban Amherst, exacerbating urban disinvestment and peripheral expansion in Buffalo. In all of these places, suburban growth exacerbated racial segregation, and universities were part and parcel to suburban growth. In Austin, understanding the the relationship among segregation, metropolitan growth, and higher education is essential to understanding the development of the city.

The University of Texas helped pave the way in the 1930s and 1940s to a new kind of sprawling, segregated metropolis, just at the moment Austin was becoming a major American city. In this era, the university drew on federal resources to promote growth in Austin, reinforced Jim Crow in central Austin before the antisegregation Sweatt and Brown cases, and, fueled by oil, helped drive a less explicit metropolitan segregation afterward. Suburbanization, highway building, and metropolitan expansion after World War II provided opportunities to sidestep political opprobrium and seemed to leave behind the legacy of Jim Crow, especially after a losing court battle over segregation. Postwar metropolitan growth allowed UT leaders to partner with Austin’s civic elite and develop sprawling greenfield and automobile-oriented sites that were functionally segregated by race while they advanced a race-neutral ideology of scientific discovery, regional economic growth, and consumer choice in the national interest. University president Theophilus Painter, politicians James “Buck” Buchanan and Lyndon Johnson, mayor Tom Miller, publisher Charles Marsh, and chamber of commerce head Walter Long—all worked together to draw federal funds, to bring economic growth to Austin, and to make it one of the boom cities of the twentieth century. Many large cities during the century lost population, tax base, and civic optimism as they suffered from urban crisis. Austin was one of the winners, with a growing population and a tech economy that made it a model for other cities at the end of the century.

The University Landscape

The University of Texas opened in 1883 after the state’s constitution authorized the creation of a “university of the first class.”6 The impoverished state could not provide the resources necessary to realize this ambition, and the modest income from the West Texas ranch lands limited the university’s growth. Dirt paths crisscrossed campus as students wore down the grass and their trails became permanent, dusty walks. At the turn of the century, a Victorian-Gothic structure, built wing by wing in the 1880s and 1890s, was the university’s signature building, but after just a few decades, it seemed antiquated and unfashionable.7 The need for classroom space was so dire that a set of rickety wooden structures built during World War I remained for more than a decade, stretching in lines across the campus.8 Students reviled them as “the shacks,” and campus wags joked that the university featured “shackeresque” architecture. A faculty member called them “hideous and uncomfortable, the shame of Texas.”9 The university sought to use oil revenues in the 1920s to begin expanding, bypassing a constitutionally created endowment fund. The state attorney general challenged this action, prompting the state supreme court to acknowledge that “a shackless campus is much to be desired,” even though it ruled in favor of the attorney general (Figure 13).10

In 1928 the university constructed a new sculptural gateway on the campus as a monument to the Southern Lost Cause. Statues of George Washington, Jefferson Davis, Woodrow Wilson, Robert E. Lee, James Hogg, John Reagan, and Albert Sidney Johnston lined the main campus walkway from the south. A dispute that began in 1919 had led to their erection, as two regents, George Brackenridge and George Littlefield, battled for control of the campus location and its appearance.11 Brackenridge was a northerner, a Republican, and a longtime UT Regent. He was a banker who had made a fortune evading the Confederate blockade on cotton exports during the Civil War.12 He donated land along the Colorado River to accommodate a new, larger campus for the university, but Littlefield, a staunch segregationist, Confederate veteran, and native Texan, opposed the move. Littlefield had fought and been wounded in the Civil War and was saved by his slave. After the war, Littlefield moved to Austin along with his wife, Alice, and Nathan Stokes, the slave who remained as a servant for more than fifty years.13 The Northern–Southern dynamic of the campus debate set the tone for decades of imagining the future of the UT campus.

Figure 13. “The Shacks” in Austin. The University of Texas suffered from limited state funding from the time of its creation, relying on the leasing proceeds of ranch lands in West Texas. These buildings were constructed for temporary purposes in World War I but continued to be used for more than a decade. Austin wags dubbed the buildings “the Shacks.” The discovery of oil on the ranch lands gave the university the resources to remake its campus despite the economic crisis of the Great Depression. UT Texas Student Publications, Prints and Photographs Collection, di_06442, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

George Littlefield donated $250,000 for a fountain and the sculptures that would embellish the approach from the state capitol, symbolize the university’s commitment to the Lost Cause, and keep the main campus in central Austin. Littlefield and Brackenridge both died in 1920, and Texas politicians battled over the plan to relocate the campus to the banks of the Colorado. With the key patron for relocation dead, city business interests rallied to keep the university downtown. The campus remained centered on the original forty acres, just a few blocks north of the state capitol, while the university used the Brackenridge tract as a golf course it leased to the city of Austin until the 1970s.14

The sculpture commission conformed to a broader agenda within Texas to emphasize a Confederate identity for the state after Reconstruction.15 Littlefield had contracted with Pompeo Coppini, an Italian sculptor based in San Antonio. Coppini provided the design, even though his vision did not entirely conform to his patron’s. The sculptor hoped to show how World War I unified the national rift of the Civil War, while Littlefield sought images of Southern heroes.16 The Southern military and political heroes depicted in the statues (as well as Woodrow Wilson, a Southern segregationist) made a clear statement, visually and symbolically asserting white supremacy to the next generation of Texas leaders. Thus, the Confederate veteran’s gift affirmed Texas as a self-consciously Southern state and implicated the university as a fundamental part of this racially segregated ideological project. Jim Crow, however, would not be limited to symbolic statements, either on campus or in the city of Austin (Figures 14 and 15).

Segregation in Austin

Austin in the 1920s was a small capital city perched on the verge of tremendous growth. It was bigger than Muncie, Indiana, but smaller than El Paso and Fort Worth, Texas cities that were double and triple Austin’s population, respectively.17 Railroads, including the International–Great Northern and the Southern Pacific railways, passed by lumberyards and warehouses along Third and Fourth Streets and crossed the Colorado River west of the Congress Street Bridge. These rail networks connected Austin producers and merchants to regional and national markets for agricultural goods such as animal hides and pecans.18 The national highway system touched urban Austin in name but hardly connected points within the city, let alone across the state. State institutions besides the university provided employment stability, including the school for the blind in the city proper and military camps in the region. Most of the business economy in Texas, the nation’s fifth most populous state, flowed elsewhere, however. Oil money funneled through Houston and banking through Dallas; Galveston had long served as the state’s chief port. As the Texas capital, Austin’s top commodity was politics. Like the state’s position in the region, it served as both a geographically central point and a metaphorical one where east Texans of the Old South mindset brokered compromises with politicians from the urban centers, the ranching hill country, and the agricultural panhandle.19

Figure 14. Littlefield Fountain. Pompeo Coppini sculpted Littlefield Fountain as a gateway from downtown Austin and the state capital to the campus. It was a symbolic statement depicting Columbia aboard a ship representing the American project. Along with a series of statues of Southern and Confederate heroes, the fountain represented the resolution of sectional difficulties but affirmed the university’s commitment to white supremacy. Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/kewing/8702417281/sizes/l.

Figure 15. Jefferson Davis statue. The president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, was one of the Southern heroes depicted in statues at the campus gateway. Larry Murphy, UT News and Information Bureau, Prints and Photographs Collection, di_02469, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

Census Day 1930 documented the segregation of the era. Two white Austin census takers, Bessie Carpenter and Flossie Pluenneke, traveled to different parts of the city and wrote down demographic data for Austin residents. Carpenter was the wife of an auto salesman and mother of two children, an eleven-year-old boy and eight-year-old girl; they lived in Nowlin Heights, a comfortable subdivision of white residents near the university campus, and owned a home worth $5,000, which put it among the top third of Austin homes.20 Over the first two weeks in April, Carpenter started going door to door, taking the census from the southeastern corner of campus, snaking through a white working-class neighborhood that shifted to white collar farther north. Walking the surrounding blocks on the eastern and northern edges of campus, she knocked on doors of homes almost exclusively filled with white residents. Along the way, she moved through just one black neighborhood centered on Swisher Street. It was one of the few remaining clusters of African Americans outside East Austin that had once been dominant areas of black life.21 Carpenter also surveyed a handful of isolated Hispanic households in the course of her work. Most rented modest apartments, while a handful of the black Austinites on Swisher and Cole Streets owned their homes. Though her house was in the top third in Austin, it was more expensive than all but two Mexican American–owned homes in the city, and fewer than thirty African American families owned houses more valuable than her comfortable but by no means ostentatious house.22 The fruits of a growing economy were out of the reach for almost all of the city’s black and Hispanic population.

Flossie Pluenneke, who surveyed East Austin, rented her home in Hyde Park, an exclusive development far north of the UT campus.23 She and her husband, a physician, had a fourteen-year-old daughter. Platted in the 1890s, Hyde Park had been a suburban neighborhood with Victorian and Craftsman homes at the very outskirts of Austin, but by 1930, it was well within the city limits. Most residents were white-collar professionals—the two neighbors across the street were a lawyer and a pharmacist—and of its 1,500 residents, the only one who was not white was a live-in domestic worker, Rose Gooden, a black cook who worked for a prosperous lawyer.

Pluenneke’s daily path illustrated the city’s racial stratification. She began her two-week walk on the 1800 block of East Avenue, the large north–south street that was one of the city’s transportation arteries and the boundary between East Austin and downtown. The first block of East Avenue was all white—clerks and grocers and office printers—except for one black family. A block south, every house on both sides of East Avenue was occupied by African Americans who worked in the service class. As she moved farther into East Austin, the most heavily segregated of the city’s African American neighborhoods, her path snaked around the city’s black schools and churches and a handful of Hispanic neighborhoods in East Austin, a neighborhood of cottages and small bungalows. Pluenneke tallied black income and jobs in Austin’s Jim Crow society that were lower than whites’ and reflected constrained job opportunities. Indeed, more than 85 percent of working black women held jobs as maids, cooks, servants, or laundresses for white families or white institutions.24 Black men hardly fared better: two thirds of the black workforce in Austin were either laborers, porters, servants, cooks, waiters, chauffeurs, or launderers.25 In a city with two African American colleges in East Austin, even those with higher education had low-prestige jobs. Black home values were also lower than those of white-owned homes, thwarting a key means of accumulating wealth and concentrating that disadvantage in black neighborhoods. The census revealed the spatial aspects of racial segregation as well as its social and economic implications.

Residential racial segregation was part and parcel of the project of urban development in Austin. In the 1920s, it was a city in transition. Civic leaders pursued a Progressive-type agenda of good government and urban order, including adoption of a council-manager form of government in 1924, establishment of the Austin City Plan Commission in 1926, and a civic improvements campaign called “Onward Austin” that drew on emerging ideas about economic development and urban planning practice. The civic agenda included the preservation of segregation but advanced in fits and starts. The Austin Chamber of Commerce helped promote passage of the Love Bill, which enabled Texas cities to pass racial segregation ordinances.26 Throughout the 1920s, Southern cities including Dallas and New Orleans established such measures. When they failed legal challenges, Southern city leaders needed to find new methods of segregating.27

Austin turned to city planning to institutionalize separation of the races. In 1927, the city plan commission invited Will Hogg, chairman of Houston’s plan commission, to discuss a plan for Austin. Hogg had gone on record with the Houston commission: “Negroes are a necessary and useful element of the population and suitable areas with proper living and recreation facilities should be set aside for them. Because of long established racial prejudices, it is best for both races that living areas be segregated.”28 Yet explicit racial zoning had been deemed unconstitutional, and so it would not be among Austin’s instruments of urban development.

That same year, the plan commission hired Koch and Fowler, a Dallas engineering firm, to create Austin’s first master plan.29 Traffic and transportation, public services, land use—for the first time, all of these would be considered in concert, and the planners would present a unified vision for the city’s future. The university contributed its expertise to the endeavor through an alumnus, Hugo Kuehne, who served as a local representative for the plan and later helped create the UT architecture program.30

Koch and Fowler’s 1928 plan proposed a service district in East Austin where the city would locate public facilities for African American residents. The report recommended that “the nearest approach to the solution of the race segregation problem will be the recommendation of this district as a negro district; and that all the facilities and conveniences be provided the negroes in this district, as an incentive to draw the negro population to this area.”31 In the 1910s, white residents of West Austin had fought a bitter battle against an African American school there, arguing that black residents would follow black schools.32 Koch and Fowler turned that logic around in their 1928 plan, which went public as a special insert in the city’s leading newspapers in February.33 The press discussed Austin’s “racial segregation problem”—not the inherent unfairness of it or its cost to society, but the barriers to effective segregation. Even though the city’s Hispanic population, at greater than five thousand, was more than half the size of black Austin, far less anxiety attended segregation of the city’s Hispanic population. Largely Mexican American, they lived in two neighborhoods, one at the foot of Congress Avenue near the Colorado River, and one in the southern part of East Austin. There was no planning effort to concentrate the city’s Hispanics in either of the two districts. The color line was drawn more boldly between black and white than it was between brown and white.34

Koch and Fowler’s report planned a segregated city that would at least double its size, reaching three to five miles outside of the boundaries in 1928. Civic leaders accepted the plan and set an election for city bond issues worth $425 million in the spring of 1928 to fund the infrastructure improvements it called for, including road paving, more and better school buildings, and parks and leisure spaces. The business community was squarely behind the “Onward Austin” campaign that would guide development for several decades.

Everett Givens saw the bond election as an opportunity. Givens was a dentist and business leader, one of only seven black medical professionals in the city.35 He was a native Austinite but had gone to Howard University for his dental training, returning to Austin to practice.36 “Insofar as you could say that [black] Austin had a political boss when I came here … it was Dr. Everett Givens,” a political rival later remembered.37 A longtime Austinite called Givens “a bronze mayor.”38 Givens was part of a generation of black leaders who sought equalization long before integration rose to the fore of the civil rights movement.39 He had inherited the mantle of black leadership from an earlier generation; the philosophy of Booker T. Washington had guided those predecessors, who advocated self-improvement rather than radical social change.40 While Givens made greater demands on Austin’s leaders, he did not question the fundamental logic of segregation.

Bond elections empowered black voters, and this was a rare moment to exercise their political clout. Whites largely excluded African Americans from Democratic primaries, which were the de facto general elections in the one-party South.41 They could intimidate voters or exclude black citizens from being members of a private political organization. Bond issues, however, were general-election votes ostensibly guaranteed to majority-aged citizens. Poll taxes, however, constrained the franchise to more affluent and business-friendly parts of the black electorate. Passage of a bond required a supermajority, a two-thirds “yes” vote. These elections were often closely divided, making African Americans—nearly 20 percent of the city’s population—a key swing constituency. A bond election had failed in 1926 without black support, and the city’s boosters would not let that happen again. They also consulted retired postal clerk Dudley Woodard about the black community’s likely response to the bond issue. Woodard estimated that 95 percent of black voters would go along with the property-tax increase if they received infrastructure improvements from the program.42 East Austin desperately needed road improvements. Only three streets east of East Avenue were paved, and the rest were packed dirt and gravel. East Avenue itself, the main thoroughfare on the eastern side of the city, was hardly paved and had no paving at all north of 19th Street.43 Boggy Creek, a small tributary to the Colorado River, ran across roads and through backyards to make a swampy mess of impassable streets and marshy lots.44

Everett Givens also prodded city leaders to devote some of the bond-funded infrastructure to East Austin, to which they agreed. An activist recalled some decades later that Givens “got where he could get…. He believed in not stirring up things. Keeping people quiet. ‘Let me take care of it.’”45 Addressing a crowd of his friends and neighbors at a public outreach meeting in April 1928, Givens said, “We believe in the bonds, and all that we ask is that we get a dollar’s worth of value for every dollar spent.”46 Woodard also held promotional events for the bond election, convincing black voters to approve the measure.47 The bond program particularly appealed to the property-owning class of Austin African Americans who could pay the poll tax: the improvements would make their land more valuable.48 Austin’s African American wards supported the bonds overwhelmingly, which passed strongly all across the city.49

The dual-track infrastructure of Austin would not have been possible without capital from financial markets drawing investment from outside Texas. The city marketed the bonds in New York, and notices ran in the financial papers.50 Thus, the financialization of public infrastructure and the implementation of an openly segregationist plan spread north. Violence in the form of lynchings, house bombings, and race riots were clear and localized ways that whites maintained the color line in communities.51 Financial instruments disguised culpability for the color line. Government bonds spread responsibility for Jim Crow—and profit from it—to investors around the country.

By 1929, Austin had millions to spend, and the infrastructure plan began to work. The black community got its paved roads in East Austin, a public library branch, and a public school.52 The city’s black elites already lived in East Austin, and with each passing year after 1928, more African Americans moved to East Austin from their enduring neighborhoods of Wheatsville northwest of the UT campus, Clarksville west of downtown, and South Congress across the river. Ada Simonds, whose family moved from Clarksville to East Austin early in the century, remembered the segregation worked “because people are going to go live where the facilities are. The family needs recreational resources, the family needs educational resources, they need a place for a church…. You’d be closer to the church. You’d be closer to this and to that and to the other.”53 The racial geography became even more segregated under the Koch and Fowler plan, making the city’s white sections whiter and black neighborhoods blacker.54 Segregationist city planning first redrew the color line on city maps, then slowly on the city landscape, house by house and block by block (Figures 16 and 17).

Figure 16, 17. Census maps of Austin, 1930 and 1950. At the turn of the twentieth century, the African American population was distributed in neighborhoods throughout Austin, including Wheatsville and Clarksville. A city plan in 1928 and infrastructure program sought to segregate African Americans in East Austin, draining them from the mix of traditional neighborhoods throughout Austin. Maps created by the author. Census data from University of Minnesota Population Studies Center, www.nhgis.org.

Rivers of Oil

Back on campus in 1930, the university was ready to build. Texas A&M and the University of Texas had waged an institutional feud from 1923 to 1930 over royalty payments for the oil. The state legislature required drillers to pay one-eighth the value of the oil to the university, to be deposited in a fund for investing in the university’s buildings and grounds. Texas A&M had appealed for a portion of the oil proceeds because they were technically a branch institution of the University of Texas.55 After much negotiation, in January 1930, the UT Regents settled the dispute with the directors of A&M, agreeing to give A&M one-third of the royalties and freeing the funds from litigation and negotiation. The Texas state legislature institutionalized this agreement in 1931.56

William Battle knew the value of architectural symbols and concrete buildings. He had played politics effectively when he served as an acting UT president from 1914 to 1916, overseeing the creation of UT’s architecture building, Sutton Hall, designed by Beaux-Arts architect Cass Gilbert. Battle was a professor of Greek and Latin, was familiar with classical forms, and was a key go-between to the city’s business class through the Town and Gown social club, a collection of the city’s leading citizens. He was one of ten UT presidents and numerous university officers who were members of Town and Gown at some point in the organization’s first fifty years.57

University development policy was often debated and negotiated in civic groups and alumni organizations, keeping college life and city life in synch. Battle maintained relations with commercial, legal, and political leaders like Walter Long, of the city’s chamber of commerce, on behalf of the university.58 Long served for decades as the public face of Austin’s business interests and credited the campus building program as a key bulwark against the Depression. The chamber promoted the idea of UT investing its oil money in higher-yield securities so that more revenue would lead to a larger building program. Enabling amendments to the state constitution passed handily, and UT construction proceeded apace.59 Among academics and civic boosters, there was little doubt that the interests of the city and the university were one.

Tom Miller, Austin’s long-serving mayor throughout the midcentury decades, made the university-city nexus a metropolitan political issue in his first run for office. He wrote in a full-page newspaper advertisement in 1933, “I will further cordial relations between the city government and State and University authorities. I am also conscious of the great asset in material and cultural value of all the other great schools of Austin.”60 To a broad phalanx of political, business, and social organizations, the effects of the university on the city were clear, and there was a consensus that the two should work together: the growth of one should spur the other.

In 1930, university officials expected UT would prosper despite the nation’s deepening economic depression. The university’s oil lands had produced about $3 million in revenue, and Texas was poised to build with its share.61 Like the city, the University of Texas sought a new master plan to accommodate its future growth. This expansion would encompass more than a dozen new buildings and facilities. Battle led the university’s committee on campus grounds, and he recommended Philadelphia architect Paul Cret for the campus plan, a marker of UT’s ambition to rank among the nation’s top universities.62 Cret was a Frenchman who headed the University of Pennsylvania’s architecture school. Through his private firm, he designed buildings and monuments across the United States and Europe. The architect was born in France and trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He brought the aesthetics of European architectural refinement to Texas. Battle termed him “a man of great ability, the highest training, and notable taste.”63 All of his work for UT would be cloaked in the style and ornament of the Spanish Renaissance Revival.

Cret delivered the master plan in 1933. It showed axial arrangements and pathways bounding and connecting rectilinear campus zones consistent with Beaux-Arts principles. He adapted it to the local conditions by creating multilevel terracing to accommodate the sloping Austin landscape. He developed schemes for new buildings, and, when selected as the architect for individual buildings, Cret provided designs and ornamentation that alluded to and, in some cases, rivaled palacios in sixteenth-century Spain (Figures 18 and 19).64

Cret’s master plan for the University of Texas was urban planning ideology writ small. The Beaux-Arts tradition and City Beautiful movement emphasized urban order by creating grand boulevards, using visual symbolism, and harmonizing the chaos of large and growing cities. Cret’s plan reinforced gender and racial segregation on campus and in the city by creating campus zones that prescribed areas of activity and reinforced geographic concentrations. It called for UT’s white female students to live and study as far on campus as possible from segregated, black East Austin.65 The zone in the northwestern corner of campus included women’s dormitories, the women’s gymnasium, and a building for home economics. Cret located the zone near two existing dormitories created for women in the 1920s, the Scottish Rite Dormitory and Littlefield Dormitory. A Masonic organization had built Scottish Rite just off the northern edge of campus to provide housing for the daughters of masons at UT. The Littlefield family had donated funds for a dormitory for first-year female students, built at the corner of Twenty-Sixth (now Dean Keeton) and Whitis, and it was the northwestern anchor for the women’s zone. To the southeast of campus, Cret’s plan also used the existing Texas Memorial Stadium, along with new parking, men’s housing, athletic fields, and open space, as a buffer between East Austin and campus.

Figure 18. Paul Cret campus plan perspective. Paul Cret, a leading Philadelphia architect, created a Beaux-Arts master plan for the University of Texas campus. Flush with revenue from leases on the oil lands, the university commissioned Cret to design more than a dozen buildings between 1930 and 1945. In this era, the university fulfilled its ambition to become a “university of the first class.” University of Texas Buildings Collection, Alexander Architectural Archive, University of Texas Libraries, University of Texas at Austin, Paul Philippe Cret Collection, Project # 241.

Figure 19. An overhead view of Cret’s design. University of Texas Buildings Collection, Alexander Architectural Archive, University of Texas Libraries, University of Texas at Austin, Paul Philippe Cret Collection, Project # 241.

Cret’s plan followed leading planning practice. The top guide on college design, Charles Klauder’s College Architecture in America, indicated, “Girls especially like to carry on all the activities of home life under their own roof.” Klauder recommended closed, “homelike” dormitories with as many amenities as possible provided on the premises. This would preempt “the inconvenience, loss of time and exposure of making an outdoor journey” for women.66 Thus, the design called for dormitory groups with house mothers and deans of women supervising them. Students also lived in nearby female rooming houses in respectable neighborhoods like West Austin. Claudia Taylor, the future Lady Bird Johnson, while an undergraduate in the 1920s and 1930s, lived in a women’s rooming house on West 21st Street near the western edge of campus.67 Formerly the home of a prominent family in one of the more desirable neighborhoods in nineteenth-century Austin, the building was inspected by university administrators to “enforce certain standards relative to sanitation, health and social environments.”68

These designs and policies enabled the college to regulate the behavior of its female students and had the progressive effect of making parents and administrators comfortable permitting women to seek higher education. Predominating mores often precluded women from pursuing degrees at all. At the end of the nineteenth century, women’s attendance at American institutions of higher education was rare, radical, and highly constrained.69 Bureaucratic controls such as deans of women, housing inspections, and house mothers, as at Ball Teachers College in Indiana, maintained campus discipline and standards for chaste and nurturing environments, encouraging conservative communities to send their daughters to university. Cret even recommended the university build a wall or fence around the women’s dormitory group, which would mimic Ivy League institutions.70 UT did not build the wall, but the administration recognized that growth in higher education could exacerbate social tensions and sought designers who brought physical solutions to these problems.

A New Deal for Austin

The national economic crisis raised the stakes for UT expansion. Across the country, the contagion of the economic crisis had spread from finance to higher education. College and university enrollment declined nationwide nearly 10 percent from 1931 to 1933, back to its 1925 level.71 That enrollment drop seemed even more dramatic since it followed a decade of continual growth. Admissions officials across the country flipped from seeing rising numbers of more than 50,000 new students per year in the late 1920s to confronting drops of about 50,000 students per year in the early 1930s.

The construction industry had collapsed and found no help on college campuses. Nationally, construction spending dropped from $11 billion in 1928 to $3 billion in 1933. Employment fell from 2.9 million in the summer of 1929 to 1 million in 1933, and, according to one assessment, nearly three-quarters of the construction workforce was out of a job.72 At the end of the Roosevelt administration’s first hundred days, Congress passed the National Industrial Recovery Act, which created the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works, more popularly known as the Public Works Administration, or PWA. It stepped into the breach with grants and loans to public institutions, putting architects, engineers, surveyors, and construction workers back to work.73

Franklin Roosevelt laid out his approach for spending billions of dollars for public works in his first inaugural address. He proposed “to put people to work … but at the same time, through this employment, accomplishing greatly needed projects to stimulate and reorganize the use of our natural resources,” balancing and developing rural and urban markets for agricultural and industrial production and consumption.74 The university construction subsidies of the PWA not only put unemployed architects and building contractors to work; it also helped expand institutions that were becoming central to the future of American intellectual, scientific, and economic development.75 Roosevelt trumpeted the federal investments in higher education, saying in 1936, “I am proud to be the head of a Government … that has sought and is seeking to make a substantial contribution to the cause of education, even in a period of economic distress.” He noted the central role of “bricks and mortar and labor and loans.”76

New Deal funding for higher education helped achieve two key goals: reorganization of the nation’s political economy and development of new means to achieve federal ends. PWA funds for universities and National Youth Administration jobs for students were investments in middle-class institutions and in the future of new white-collar workers. These college students were business people and industrial engineers in the making, budding members of the medical and legal professions, and workers who would staff the administrations and bureaucracies of public and private institutions, using the skills and ideas learned in their college days. The New Deal helped keep students in college courses during the Depression, but it also made more and bigger classrooms to hold them, helping expand the capacity of higher education in the 1930s by approximately one-third.77

At the same time, New Dealers worked through nonfederal channels as much as possible to provide this aid. The PWA supported private enterprise with grants for hiring workers and firms rather than employing laborers directly. While the Roosevelt administration was stimulating and reorganizing the use of American resources, it was recruiting a wide array of institutions to more directly and intensely create, exploit, and provide these resources, from education to housing to infrastructure to financial instruments. Colleges and universities came to constitute a “parastate,” an intermediate means through which the federal government could mold students into citizens and provide them services, while remaining at arm’s length.78 The New Deal became less visible, and, while federal aid became more important to higher education, this support was often masked and not recognized as such. These two features, the investment in capacity and the use of nonfederal means, combined to lay the foundation for a new economy after World War II, led by an increasingly educated workforce that was, ironically, less committed to the pillars of New Deal liberalism, including collective bargaining in the industrial sector, as time went on.

The spatial nature of these investments could boost or burden local communities as the federal government worked with local partners and channeled aid to a chosen set of institutions. Congress created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1934 to help stabilize and expand housing markets across the country. The agency wrote a manual for mortgage underwriters in order to standardize procedures for receiving a federal mortgage guarantee. The FHA favored stable, white, middle-class neighborhoods for committing its funds and incentives. In the manual, FHA experts specifically invoked the beneficial effects of colleges, which worked to protect and buffer desirable areas. The manual noted that “a college campus often protects locations in its vicinity” and compared it to other protective measures and natural features that would “prove effective in protecting a neighborhood and the locations within it from adverse influences … includ[ing] the infiltration of business and industrial uses, lower class occupancy, and inharmonious racial groups.”79 Through the FHA, the Roosevelt administration made this protective feature of higher education an operational feature of its housing policy. Investments in universities like the University of Texas were acknowledged to increase urban segregation by protect neighboring white homeowners. Each new building at UT advanced the cause of segregation in higher education and in Austin.

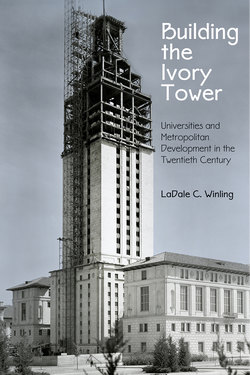

Federal funds and oil revenue allowed the university to become the “university of the first class” the Texas constitution had promised. Between 1930 and 1940, UT built fourteen structures designed by Paul Cret. Oil royalties were deposited in the Permanent University Fund and could be dispersed from the Available University Fund. In 1929, the latter fund held $800,000 for construction and would accrue millions of dollars a year by the end of the 1930s.80 The PWA required local matching contributions for most projects, and UT could easily make these contributions.81 The PWA provided grants and loans for seven UT buildings, including the signature Main Library building, five dormitories, and a laboratory building. PWA aid totaled more than $2.7 million, making the University of Texas one of the largest recipients of building aid in the country. The Main Library and administration tower was the second-largest allotment for a single building in the country.82 The University of Texas tower reached twenty-eight stories and 307 feet in height, nearly the equal of Austin’s state capitol building (Figure 20).83 The ultimate consequence of federal aid to higher education in this era was to create more capacity at colleges and universities like the University of Texas. PWA and WPA funds made it easier and more democratic to pursue higher education—largely for whites—and provided investment in new research endeavors and professional schools.

Figure 20. Library Building Tower. The Library Tower and Main Building at the University of Texas was financed with a combination of oil revenue and New Deal aid. It was the second largest Public Works Administration grant for a university building in the country, with Hunter College in Manhattan receiving the largest. Walter Barnes Studio, Prints and Photographs Collection, di_04018, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

The New Deal helped the University of Texas and other institutions like it indirectly as well, by boosting Lyndon Baines Johnson’s career. Perhaps more than any other Austinite, Johnson recognized how the Roosevelt administration could help the city bring about a new metropolitan order. He built his congressional career on his ability to work Washington connections and bring federal resources to the Texas Tenth District, especially as part of an urban development agenda for Austin. Johnson brought federal slum clearance funds to East Austin, plowed into three segregated public housing projects. Rosewood Court was built for black residents, Chalmers Court was for white residents, and Santa Rita was for Latino residents. Johnson arranged for loans and grants to the Lower Colorado River Authority for dam construction, electrification, and flood control, putting people to work and bringing electricity to the hill country outside Austin. The congressman also coordinated the development and exchange of military assets, as with the land that became Bergstrom Air Force Base and then Bergstrom International Airport.

For politicians like Johnson, investments in higher education were one part of an urban development strategy. The land and plans and brick and mortar that went into construction had the same kind of employment impact on a college campus as they would in building a public housing complex. Austin leaders arrayed those investments within the city, whether public housing or college dormitories, to harden the spatial and social system of racial segregation. Thus, the city’s African Americans might benefit from federal slum clearance, but white college students at segregated universities like Texas received the education subsidies of relief jobs and affordable dormitories that would allow them to become middle-class professionals. Slum clearance projects like Rosewood Court continued the system of geographic segregation; so even when Austin’s black population gained from the New Deal, those gains were bounded in ways that continued to limit their prospects.

Changes in World War II

Roosevelt’s reform impetus took a different turn as the administration mobilized to prepare for war in Europe. “Dr. New Deal” became “Dr. Win-the-War,” in Roosevelt’s phrase, as mobilization for World War II brought the military to campus.84 The federal government had grown in unprecedented ways in the course of the New Deal, but the Roosevelt administration pivoted from economic recovery to military mobilization. These often haphazard experiments in statecraft nonetheless evolved during the war as the federal government increased its control over society. They changed the nature of the federal government and its relationship to the American people through rationing, taxation, and new levels of spending, to name just a few areas. The American military’s struggle to scale up training of personnel after the bombing of Pearl Harbor led to the creation of numerous education programs in partnership with colleges and universities. Higher education had struggled to rebound from diminished enrollment during the Depression and faced a loss of students again. Colleges sought ways both to support the war effort and to keep their enrollments up. President Roosevelt requested that the secretaries of war and of the navy “have an immediate study made as to the highest utilization of the American colleges,” and the U.S. Navy stood out for creating several wartime programs to train its officers, including the V programs involving thousands of students.85

Research funding brought the war into the campus laboratory, a war of the minds waged on campuses against the Axis powers. In Washington, Roosevelt advisor Vannevar Bush counseled the president on the creation of the National Defense Research Committee and its successor, the Office of Scientific Research and Development, to “correlate and support scientific research on the mechanisms and devices of warfare.”86 The varied types of military research amounted to a war of the minds waged on college campuses against the Axis powers. The Manhattan Project developing the atomic bomb is the most prominent in public memory, but research projects led to military applications large and small and built up the American war machine. At UT, the physics department established the War Research Laboratory in 1942 to coordinate contracts with the Office of Scientific Research and Development and home to projects that calculated ordinance trajectories and improved gunsights for B-29 bombers.87 Charles Boner, a physicist with expertise in acoustics, worked on sonar technology at Harvard University and at UT directed a naval ordinance research project, then the Defense Research Laboratory after the war’s end.88