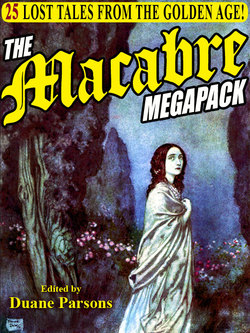

Читать книгу The Macabre Megapack - Lafcadio Hearn - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE SILENT MAN, by Henry Fothergill Chorley

(1832)

There are periods in every man’s life overcast with gloom and difficulty—when the day is full of trouble, and the dreams of the night of disquiet; and when the pilgrim is ready to lie down with his burden and die, because there is no hand to help him. Such a period in mine was comprised in about fifteen months of the years 1793 and 1794, which I spent in a large sea-port town in the north. I was then three and twenty; and the concurrence of many perplexing and calamitous events cast upon me on my entrance into life a load of care, from the pressure of which I then thought it impossible that I should ever rise.

During the winter of 1793, I inhabited an ancient and deserted house in the quieter part of town; its extensive suites of dim and decaying rooms scantily furnished were not a residence calculated to restore a cheerful tone to my spirits. The property had been suffered to fall to ruin; and the conclusion of a long protracted law-suit was alone awaited, to level the stately old mansion with the ground, and to dispose of the land on which it stood for more profitable purposes. Behind it lay a melancholy and weed-grown garden, shaded by large dingy elms and poplars; in the centre of this was a stagnant fish-pond, flanked on one side by a ruinous summer-house, on the other by the glassless frames of a conservatory. Beyond this dismal spectacle was seen the taper spire of a church, and, yet more dimly in the distance, cumbrous piles of warehouses, which stood up in the busier parts of town; silent edifices of wealth and activity, strangely contrasted with the desolation of the foreground.

I had sat, one night, poring over old papers, until the midnight chime warned me up stairs to rest. I had chosen my sleeping room to the front; it was small, but the better for that in a house where increase of space was also increase of dreariness. The feet of my bed faced the window; and close to my head was a door, which I could open and shut without rising. For the further understanding of my scene, I must say that my room was at the top of the principal staircase, which was lighted by an immense Venetian window in the back of the house, the height of two stories.

On the night of which I speak, I suppose that I fell asleep soon after I went to bed. I know that my dreams were of agony, for I woke with a start, and found myself sitting upright, my forehead covered with a cold perspiration. As soon, however, as I became fully awake, I was surprised with an unusual appearance upon my glass which stood upon the table in the window. In the centre of its dark, oblong field there burned a small but intense spot of steady and living fire, irregular, but unchanging, in shape, and casting no glimmer on any surrounding object. In my first confusion, I was unable to reason upon what I saw; a second look convinced me that it must arise from the reflection of light through the keyhole of my chamber-door. At once it struck me that someone must be without; and, anxious to ascertain who it could be, and with what intent come thither, I sprang out of bed, and, after waiting an instant for sound or signal without, and hearing none, I threw the door open wide.

The sight which met my eye was sufficiently awful, though different from what my heated imagination had conjured up; being neither robber nor visitant of a more appalling character (for, be it known, my present residence was haunted). When I opened the door, a flood of light brighter than the blaze of noonday burst into the room, filling every remote corner, and showing every object without—the broken balustrade of the massy oak staircase, and the cobwebs on the large, round-headed window—with wonderful directness. The tops of the trees in the garden had caught the glow; the spire of the church seemed swathed in gold; and behind these, the cause of this illumination, a volume of brilliant, wreathing fire, overtopping the tallest buildings by a height equal to their own, rose silently into the sky, while above huge clouds of crimsoned smoke rolled heavily off in the north quarter of the heavens.

Every object in the immediate neighborhood of the scene of devastation was traced out with startling vividness: the groups of people on the tops of houses, sweeping to and fro, as small as pygmies; the ships in the river beyond were all clearly visible, and brought close to the eye. But to me the chief awe of this scene was its complete and unbroken silence. I was far too removed from it to hear the tumult in the streets, the hissing of the ascending flames, the cries of the helpless or the alarmed. The wind bore away in another direction the solemn toll of the fire-bell; and the whole scene, at that dead hour, wore the strange and awful guise of some show conjured up by a potent magician, it was so unlike any sight familiar to my previous experience.

After the silent gaze of a few instants, I dressed myself in haste; and, having called up my servant, and ordered him to sit up for me, I repaired as quickly as I could to that part of town where the conflagration was raging. It was nearly a mile from my house, but I needed no direction as to the precise spot, for crowds of awakened people were streaming thitherward from every quarter. Presently, as I advanced, their numbers became so dense as to make it a matter of some difficulty to proceed; and, long before I came within a stone’s throw of the spot, all further progress was impossible. The building on fire was a huge distillery: and, as the stores of manufactured spirits were reached, one after the other, enormous jets of intense colorless flame burst perpendicularly upward—the night fortunately being still—while every instant the fall of some floor or chimney was succeeded by a flight of sparks; and the sullen roaring of triumphant element was heard in a deep undertone amid the shouts of the firemen and the murmurs of the vast concourse of spectators. To give a yet deeper interest to the scene, the two unhappy watchmen belonging in the premises had been seen to perish in the flames, the spread of which had been so rapid that all that could now be hoped for was to prevent their communicating with the surrounding streets. The fire had already destroyed a court of small houses in the immediate vicinity.

Anxious to approach as near as I possibly could, it occurred to me that I might perhaps effect my purpose through a quiet, narrow street, terminating only in a warehouse which stood almost immediately opposite to the burning pile. Through this there was a thoroughfare allowed by sufferance, and with all speed I made my way around thither, through a labyrinth of alleys, in my eagerness forgetting that this warehouse was enclosed in a court shut up by strong gates, which were not likely to be open during a time of such confusion. This I found to be the case: the building was an empty one, and seemed to be left to its fate; and I was turning away in disappointment, when my attention was arrested by the scene without, which was to me more impressive than any I had yet witnessed.

The street in question was one of those anomalies which are found in the densest hearts of large towns, being quiet, clean, and dull; and the houses, of antique fashion, had been obviously built for some class of people better than that by which they were now occupied. On the causeways and in the windows stood the scared inhabitants, looking upwards in silence; and every now and then some strong man appeared reeling under a load of bedding or furniture belonging to the poor families who had lived in the court close to the distillery, and, having been awakened to a sense of their danger only just in time to save their lives, had been able to rescue little of their property. It was a touching sight to examine one face after another and to read one strong prevailing emotion upon every countenance; and it was grievous to hear the wailings of the poor homeless creatures who had been kindly received in the different houses, many of whom had lost all that they were worth in the world, the hardily accumulated earnings of years.

Apart from these and close in the shadow of the courtyard wall at the end of the street, I presently discovered an old man sitting disconsolately on a pile of stones. He was neatly dressed, but bare-headed; and his white locks were long and few. Beside him was a large chest; and while everyone else seemed to have his counselor and comforter, this sufferer alone was neglected , if not shunned; and he looked as if rooted there in stupid despair, reckless as to what could now befall him, and neither soliciting nor receiving the assistance of anyone. There was a mixture of meekness and agony in his fixed gaze, and a listless indifference in his attitude that arrested my compassion at once; and I asked a respectable woman, who was standing on a step with a child in her arms, if she knew who he was, and why the same good offices that were extended to his neighbors were so pointedly withheld from him.

“Why, sir,” she answered readily, “I should like to know who would dare to speak with him or offer him anything. He’s unlucky.”

“You mean that he is not in his right mind,” said I.

“I do not know that,” she replied, shaking her head oracularly. “He has lived in yonder court for these six and twenty years, and I do not think in that time he has said as many words to any of us—nobody but himself ever entered his house.”

“What is his name?”

“He is called Graham, we believe,” she said, “but we are not sure; no letters have ever come to him that we know of. He is well off in the world, for he does no work—and we are used to call him ‘the Silent Man.’ The children are afraid of him, though his custom was to go little abroad till it was dusk. He neither lends nor borrows, nor, so far as we have seen, goes to church.”

“And what is to become of him now that his house is burned down? Is he to sit here in the cold all night? I will go—”

“Lord bless you, sir!” said the good dame, laying her hand upon my arm, “don’t think of such a thing. Take care what you do; he will shift for himself somehow or other, I have no doubt.” And when she saw that I was bent upon accosting this singular being, she turned away from me hastily, as if afraid to share in the peril which, as her speech implied, I should bring upon myself, by offering him any assistance.

But my resolution was taken. I went up to the subject of our discourse, and touched him lightly on the shoulder. It would seem that he had been in a reverie; for he started, and looked up suddenly, and I was anew struck by the singular cast of his face. “You seem cold, my friend,” said I; “will you not come under shelter?” He made no answer, but shook his head.

“At least,” persevered I, “you cannot intend to remain where you are—it will be your death. Will you come home with me for the night, if you have no further occasion to stay here? I cannot promise you good accommodation, but, at all events, warmth and shelter—or, do you wait for someone else to join you?”

He answered in a low voice, but it was the voice and with the accent of a gentleman, “No one.”

“Well then,” said I, “you had surely better accept my offer—or, can anything more be done for you here? Is this your property—” I hesitated as I spoke, for I imagined him to be stupefied by the extent of his calamity.

“Beside me,” was his answer, pointing to the large chest.

“Then I beg you to make up your mind at once. It is far to go, it is true; but anything is better than staying here. Come—let me assist you to rise,” said I, taking hold of his arm.

He arose mechanically, as though he only half comprehended my meaning. “I do not know,” said he, in a bewildered manner, “but I suppose it is best. Thank you.”

I could make little of these broken words, but the supposition that his intellects were disordered, or that he was depressed beyond the power of speech by the total want of sympathy which had been shown him. But the common duty of humanity was not to be misunderstood; and, after addressing to him one or two other questions, to which he seemed unable or unwilling to reply, I gave him my arm. He looked wistfully down upon the chest; it was large, but, upon attempting to raise it, I felt it to be so light that I almost thought it must be empty. So, without making any further difficulties, I took it under my other arm, and, covering his bare head with my hat, we walked away slowly through the wondering people, who gave way as we passed. I was in hopes that my companion was so much absorbed in his own feelings that he did not notice this new gesture of distrust.

I never felt so totally in the dark as to what I was doing at that moment. He could not or would not speak in answer to my further inquiries, but tottered on, leaning upon my arm. It was nearly an hour before we reached the old house; and he seemed on our arrival to be so much exhausted that I directed my servant to carry him upstairs and lay him upon my bed. I caused a fire to be lighted, and administered to him such cordials as were expedient, without any resistance on his part. The only sign of consciousness that he showed was suddenly rising up and looking round him; his eye lighted upon his chest, and then, as if he were satisfied that his treasure was safe, he sunk back, and in a few moments was quietly asleep.

For me sleep was out of the question. I sat by his bedside all night, wondering in what strange new adventure I had involved myself, and shaping a thousand conjectures as to what might happen next. My mysterious guest could hardly be a poor man, for his linen was beautifully fine, and he wore a delicate gold ring upon one of his attenuated fingers. He could—but it was useless; anything beyond the wildest castle-building was impossible. And, summoning a faithful physician and clergyman betimes in the morning, I detailed to them the chances which had burdened me with so singular an inmate. I introduced the physician into the old man’s chamber; but to him as to myself was his behavior a riddle: he took no notice of what passed. The medical man pronounced it to be his judgement that the old man was suffering from exhaustion or abstinence, but that otherwise he had no symptom of disease upon him, and recommended me to allow him to lie still, and feed him as often as he would permit with nourishing food. The clergyman promised for our satisfaction to endeavor to collect some further particulars as to his history and habits in the neighborhood where he had resided; and they left me in as little comfortable state as may well be imagined.

I found no difficulty in following Dr. Richards’ suggestions. The patient was passive, took whatever was offered to him, and seemed to doze almost all the day. I could not make up my mind to leave the house, and spent the greater part of my time in the stranger’s chamber. Any attempt to engage him in conversation, or even to obtain an answer to a question, was in vain; and I can scarcely describe the strange uneasiness which I felt creeping over me when evening set in and my two friends had paid their unsatisfactory visit—I say unsatisfactory, because the physician was entirely at fault as to the state of the invalid, and the clergyman had been unable to discover anything beyond what I had heard on the previous evening. Either would have remained with me all night, but they were called to distant parts of the town by the imperative duties of their profession—and again I was left alone.

Some will, I am sure, comprehend the feeling of heart-sickness with which I took my seat by the fire. The night was wild and stormy, and I sat for two hours without speaking or moving. At length, to my great amazement, the current of my unpleasant thoughts was interrupted by the first spontaneous speech which my inexplicable guest had yet made. “Come hither,” he said faintly.

I obeyed, and stood before his bedside, waiting for an instant to see whether he would speak again—but he was silent as before. I then said—“Can I do anything for you?”

“No,” replied he promptly; “unless you will sit still, and listen to my story.”

“Anything you wish,” answered I eagerly, wondering what kind of communication I was about to hear.

“Well then,” said he, raising himself up a little—“and yet I hardly know why even now I should recall the past. Yet I will once more before I go—and it may explain to you what you ought to know. You stepped forward to assist me when I was otherwise deserted, and I am not ungrateful. But I lose time; my tales is long, and I have far to go before midnight.”

He paused; and I, taking advantage of the moment’s silence, drew my chair close to his side; and, in the midst of a storm without, wilder than I have ever heard before or since, I listened to his story.

“I have no friend or relation in the world that I know of,” said he. “I am the natural son of a nobleman—but he has long since been dead; and the title, with the estates, has passed to a distant branch of the family. From my cradle my fate was marked out to be a strange one. I was educated and pampered in my father’s house till I was eighteen, without the remotest idea that I was not his legitimate heir. Then, when he married, the veil was torn off, the delusion dissipated, at a moment’s warning. I was told of my origin, but not the name of my mother—and to this day I have no idea who she was. I fancied that she died in giving me birth—perhaps for her folly disowned by her relations, who scarcely ever heard of my existence. I was turned out of doors, with a caution that, if ever I ventured to appear in my father’s presence again, or to bear his name, I should forfeit his favor towards me, which would otherwise be continued in the shape of a liberal annual allowance.

“I had always been on a delicate frame, with feeble spirits and an imaginative disposition, but with wilder thoughts and passions than ever I had dared to reveal. You may judge how such a message, coarsely delivered to me by my father’s chaplain, a debauched old man, was likely to affect me. My father had never shown any love to me—but I loved, I depended upon, him. And now I remonstrated, I entreated, with all the eloquence of strong and indignant feelings. I begged for an interview with my unnatural parent; it was denied me, with words of opprobrium that are yet ringing in my ears. The curse of their bitterness has clung to me ever since. I left—I will not mention the name of my home—a being marked out for unhappiness—and felt, while I groaned under the load of my misery, that it was laid upon me for life.

“The world, however, was before me. I was well provided with money, young and handsome; and over the morbid sadness of my heart I threw so thick a mask of gaiety, that even I myself was at times deceived, and fancied that I was happy. I would not stay in England; but spent the next five years in exploring the continent. Italy, Germany, France, all became as homes to me. But I was alone: I had no friends, though many acquaintances; and when any one of these strove to approach nearer to the secrets of my heart than the common intercourse of society permits, he found himself repelled; and refrained from further endeavors, he scarcely knew why.

“I have no time to trace out the workings of feelings—I will only mention facts. When I was in Paris, in the year 17—, the talk of the circles was entirely of a celebrated Sybil, Madame de Villerac, a woman whose age, for she was known to be no longer young, had not impaired her wit and beauty. Her predictions were said to be astonishingly precise and correct; and she was consulted and believed in by the loftiest and wisest in the land, although there were some, of more scrupulous or timid spirits, who did not speak of her without a shudder. I was resolved to prove her skill. I was presented to her at a grand fete, given by the Spanish ambassador. She was certainly the most striking-looking woman I ever saw. I well remember her imposing appearance. She was seated at a card-table, dressed in rich black velvet, with one solitary feather waving across her brow. ‘You can play at Ecarte,’ said the Chevalier Fleuret to me, rising from his seat; and, after simply naming us to each other, he pointed to the vacant chair, and left us alone together. Before I had time to think, I was engaged in deep play with this extraordinary and commanding woman. But conversation presently stole in, and we slackened our attention to the game. She spoke with astonishing eloquence: our talk was of the world and its ways. Then I endeavored to lead it to topics of graver interest—the past and the future—and, half in badinage, half in earnest, I ventured to ask if there was really any virtue in cards to unravel the secrets of destiny. She smiled scornfully, and, looking me full in the face, asked me, in the most indifferent tone imaginable—‘Shall I try?’

“Of course I answered in the affirmative.

“‘Remember, then, Chevalier Graham,’ replied she, ‘that I am not answerable for what I shall find. Am I to tell you all the truth?’

“‘All—every word.’

“‘Once again I warn you—but I see it is thrown away. Here, then’—and I drew a card from her proffered handful. After some unintelligible ceremony, she spread them before her. For an instant she looked intensely serious—then, as if she were resolved to carry off the matter as a pleasantry—‘Good and evil, as usual,’ she said. “I am no prophetess to foretell unmingled fairy luck—what do you think of an heiress for a wife—if you are to die by her hand?’

“I half started up from my seat.

“‘Now you look as much shocked,’ said she, ‘as if I were indeed an oracle. Nay, positively not a word more’—and as she spoke she fixed her eyes very pointedly on a remarkably handsome ruby ring which I wore.

“‘I have been told,’ said I, attempting to catch her tone, ‘that the only way to confirm the good and undo the evil is to bind the Sybil in some charm. May it please you to wear this ring for me for seven years and a day, and then I shall hope to be safe—it is a talisman.’

“She took it carelessly, as a matter of course, and, placing it upon her finger, ‘Come,’ said she, ‘we will join the company.’

* * * *

“Two years afterwards I was married to the most beautiful woman in Italy, after a week’s acquaintance. I met her in Venice; and was completely dazzled by the fascinations, whether of personal beauty, or of the grace, wit, and elegance of her manners. She seemed, like myself, totally unconnected; but I asked no questions. I wore her chains; I laid myself at her feet, and was accepted. Known only as a passing stranger, I escaped all unmeaning congratulations; and, careless of the envy of unsuccessful rivals, I carried off my beautiful wife in triumph. I married her, literally, from the fancy of a moment. Nor did I discover, till some weeks after we were united, that I had fulfilled the first prediction, and that my wife was heiress to great wealth as well as the possessor of great beauty. ‘I have kept this a secret,’ said she, ‘because I was resolved never to be wooed and won for my money.’

“This was plausible, but not true. On becoming gradually acquainted with Clementine’s history, I found that she had in truth had few, if any, honorable suitors; and I was curious to discover what circumstances could have enabled me to distance all thousand of inamorati of Italy. Then she had accepted my devotions so readily, so eagerly! But my researches were in vain. There was a mystery about her not to be penetrated. I soon found that we were to be totally separate as far as the interests of the heart were concerned. What my wife’s secret was I had not the remotest idea; but her love—I should have said her liking—for me waned daily. And erelong I felt a strange and indescribable distrust creeping over me, a sense that I was tied to one who might be said to have another existence, independent of aught that I knew. I foresaw that this state of things could not last, and went on, blindly, madly, to my own undoing.

“One evening, when we were sitting together, ‘It is strange, my Clementina,’ said I, ‘that I do not yet know the name of your mother.’ She had changed hers, I had been given to understand, in order to possess some property bequeathed to her upon that condition.

“‘Do you think so?’ she replied carelessly—and then, half rising from her couch and casting a piercing look upon me—‘It is odd, too, that I forget the name of yours.’

“I was dumb, and changed the conversation. A few evenings after this, however, in passing through her dressing-room, when my wife had gone to a ball, I chanced to find her jewel-casket open. At the top of many ornaments lay a miniature. Good heaven!—and I recognized the original at once—the never-to-be-forgotten eye of pride, the stately brow, the rich, dark hair—and, to confirm my assurance, there were these words traced on the back—‘Clementine de Villerac’s last gift to her daughter’—and underneath, in a hand which I knew to be my wife’s—‘My mother died when I was seventeen’—so that I had married the daughter, the heiress, of that mysterious Sybil; while it was next to a certainty that others, knowing from whom she was descended, had been deterred from approaching her.

“I shut up my knowledge in my breast—but thenceforth my peace of mind was gone forever. Upon my gloomy and irritable temperament the possession of such a secret wrought me increasing agony. I struggled with the presentiments which it engendered: I tried reason—I tried religion, society, solitude, change of place, study—all would not do. And what was remarkable, during four years of conflict such as this, my wife never seemed to advert to what would have grieved and surprised any other woman. So long as she received her accustomed tribute of admiration, and we lived with the semblance of tolerable concord, she was content. I suppose that the privileges which a married woman enjoys were what she sought in accepting my hand, and, satisfied in the possession of these, she concerned herself no further.

“Each year widened this mutual estrangement of feeling. As Clementina’s beauty waned—and it waned early—she seemed more covetous of homage, and to allow herself greater latitude of conduct than formerly, while the mantle of my spirit grew darker and darker day by day. The second part of my mother-in-law’s prediction arose unceasingly to my recollection. We came to England; and here I perceived, with a sort of gloomy apathy, that Clementina’s deviations from a correct demeanor became daily wider—that in fact she allowed the attentions of other men in an unsuitable degree. My own father was dead, having, on his death, left me a fortune equivalent to my former yearly income. I was still young, had unbroken health—and yet God knows how often I have stood at a window of our sumptuous house and envied the most miserable beggar, old, poverty-stricken, and diseased, that crawled past for his daily alms. I had lost what little relish I ever had for the common pleasures of life. Gaming was to me no excitement, music only a source of pain, and the mere animal enjoyment of bodily exercises a weariness. I resembled one of those unhappy beings of whom one has to read in the old records of superstition, who are bound by spells that they have no power to break, and whose lives are as a long and weary dream of dull misery.

“It was about this time, now thirty years ago, that the devotion of a certain Lord Mordown to my wife became so evident that I resolved to arouse myself while there was yet time. I remonstrated with her kindly, yet spiritedly; and she as usual made no answer. On the evening of the day when I mentioned this hateful subject to her, she repaired alone to a masquerade, where she met the nobleman in question. I learned in the course of the evening, no matter how, that it was necessary that I should take speedy measures in my own defense, if at all; and, revolving many plans in my mind, I sat, in an unwonted tumult of feeling, awaiting her return.

“She came home much earlier than usual. I ran to meet her, and handed her out of her carriage. I remarked an unusual paleness on her lip, an unusual tremor of hand. ‘I am very ill,’ she said, almost throwing herself into my arms. I led her upstairs in silence. She called her maid to undress her as speedily as she could. I suppose that the seeds of some malignant disease had been lying dormant in her constitution, and that the excitement and the heat of entertainment had suddenly riped them, for in another hour she was in a raging fever. I dismissed her attendants, resolving to watch her myself. She grew worse; and about two in the morning she was seized with violent delirium, and cried out for water.

“It was the work of some demon that the prediction never occurred to me so strongly as at that moment. Will you not turn me out from your shelter? I say that the horrid idea of contradicting my destiny possessed me—so that I sat still, and called for no help. Every servant slept in a different part of the house. I tell you I sat still, listening to her ravings, with unmoved ear and cool calculating brow. ‘It will be daylight soon,’ I said to myself, ‘and the servants will be up, and will hear’—and the voice was urging me, close in mine ear, to break loose from the spell which had enchanted me for so long. I heard it say—‘Thy fate is in thy power!’ It tempted me again—I shuddered—a distant glimmer of dawn began to lighten the heavy sky—I went to my wife’s bedside, and—it was the work of a moment—the next, she lay a corpse before me.

“From that hour I was mad. Days, months, years—but let me hasten to say what I most wish. When I was released from confinement as a convalescent, I bribed the sexton of the church in which she was buried to disinter for me the remains of my ill-starred Clementina. They have been beside me ever since as a penance, as a memorial. When I am gone, open yonder chest. You will find only a few bones and a little dust, which you will restore to consecrated ground, and writings which will put you in possession of a handsome fortune. I have nothing more...”

He stopped suddenly. I hastened to call for light, the candle having burnt out in the course of his story. I supposed that the narrator had failed from exhaustion: but, when my servant obeyed the summons and I approached the stranger’s bed, I perceived he had expired.