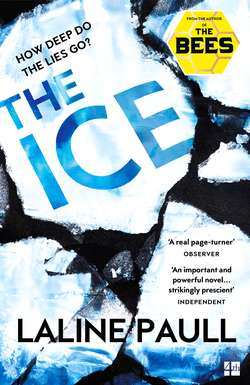

Читать книгу The Ice: A gripping thriller for our times from the Bailey’s shortlisted author of The Bees - Laline Paull - Страница 17

Оглавление5

Fourteen nations signed the Svalbard Treaty of 1920, giving each of them the right to settle, purchase property and conduct business on the archipelago, provided that, in the words of the legislation, it was ‘not for war-like purposes’. By the time Sean Cawson was writing draft after draft of his purchase proposal for the old whaling station, the Treaty had forty-three signatories and seven new-formed states seeking approval. But treaties and laws are as subject to ageing as the hands that wrote them and the times to which they applied.

Family firms likewise. The derelict structures he bought by consortium and rechristened Midgard Lodge were built and owned for two hundred years by a wealthy Norwegian family: the Pedersens.

The youngest generation rejected their elders’ pride in their whaling past, instead feeling shame that their family fortune was built on the near-genocide of several cetacean and pinniped species. It was like inherited wealth from slavery – no bar to public office, as Great Britain proved, but something they felt a debt to repay. In karmic offset, they embraced diverse environmental causes to distance themselves from the documented accounts of their forebears, of the joyful slaughter of pregnant beluga whales in Midgardfjorden, and the flensing of live walruses on the beach they still owned. The surviving elders, who still used the candelabra made of narwhal horn on Sunday nights, mourned many aspects of the past under the safe code word: Tradition. The middle generation just wanted the money, and made discreet inquiries about the old lodge on the shores of Midgardfjorden. The price it might fetch, the complications.

In Svalbard, Oslo, Bergen and Tromsø, each realtor charged with this investigation broke into a sweat at the prospect of the kill: private property for sale in Svalbard, demesne to encompass landing beach, deepwater access, and a plot reaching right back to the mountain. Of course all land permanently belonged to the Crown of Norway – but the most demurely conservative estimate of the value was stratospheric.

For once the family agreed: it was time to let Midgard go. They chose a single agent, Mr Mogens Hadbold. Very discreetly, he dropped a hint of that possibility into international waters. The feeding frenzy was almost instantaneous. First came the Norwegian government itself, who brought much patriotic pressure to bear on the family agent, who duly passed it on – noting that two Russian oligarchs (bitter rivals) had more than doubled the government’s best offer. Both were ready for a bidding war, but one was ruled out for his rapacious extractive activities in the Laptev Sea, albeit carried out by a Romanian proxy company. The other, a prominent Siberian landowner, had airlifted every polar bear within three hundred square kilometres to create a private reservation close to Moscow ‘for conservation’ where he was reputedly breeding cubs for sale as pets. He too was ineligible.

The still-patriotic Pedersens paused to consider. The property was worth far more than the Norwegian government was willing to offer; why did they not understand? Their agent explained: if the government paid the premium the Midgard property commanded, they might then find themselves hostage to any Norwegian landowner north of 66 degrees, keen to leverage large amounts of cash. This truth caused the Pedersens’ patriotism to somewhat fade.

But other bidders – from the US, Canada, Russia, China (the most) and India, were numerous. Seventy-five per cent were ruled out in the first round of investigations, but then the British-led consortium returned, demanding (‘begging really,’ said the family agent) to be reconsidered. This was because of the new involvement of one Tom Harding – a name that rang discordant bells (Greenpeace?) for the older Pedersens, but chimed most harmoniously (Greenpeace!) for the younger. He had led the charge to clear the Plastic Sargasso and driven the investigation into clinical trials corruption at more than one chemicals giant. The older generation, emotionally blackmailed by their children, allowed that the British consortium could re-submit its proposal – so long as they knew that the odds were against its success.

Long odds were what Sean Cawson had beaten all his life. The sale went through, Midgard Lodge was built and still running despite the terrible accident that had marred its birth – and three and a half years later, here he was disembarking into the sharp mineral air of Longyearbyen once more.

It was good to see Danny Long standing waiting on the tarmac. Behind him was the familiar yellow and blue Dauphin helicopter in which they would fly to Midgard, and standing by his general manager’s side, a Longyearbyen airport official ready to conclude the briefest of passport formalities.

He and Danny greeted each other warmly. There was no difference in Long’s appearance, or his comfortable quiet manner. He was everything you wanted in a pilot, and though Sean had intended to broach the difficult matters straight away – as they rose up over the slopes of the coal mine behind the airport then veered away from the town, he found he could not speak. Silently, he absorbed Svalbard’s stark beauty. This time, there was none of the churning panic of his last visit, unwisely made too soon after the accident. He was here to put that failure behind him and lead with confidence again.

Not until they had left the black peaks and steely water of Adventfjord behind them, and were beating their way over the whiteness of the von Postbreen glacier, up to the razor-tipped ice plateau of King Olav’s Land, did he clear his throat. He heard the tiny answering click and, to Sean’s surprise, the pilot spoke first.

‘I’m sorry I didn’t call you, sir, about Mr Harding. But Mr Kingsmith called, so I told him – then he wanted to tell you himself.’

‘Yes. He told me he’d put a retreat in. You know that—’

‘Yes, sir. Everything to go through London, he set me straight on that earlier today. If you don’t mind my saying, Mr Cawson, it’s good to see you again.’

‘And you, Danny. It’s been far too long.’

The pilot looked straight ahead. ‘I still feel very bad.’

‘Not your fault, Danny.’ Sean looked down at the ice.

‘But if I’d been in there with you …’

‘You were needed on watch. But thank you.’

He remembered how much he liked Danny Long. In his late forties, he was blunt-featured, of average height and stocky build, and his modest manner belied his high competence – but that was probably part of the protocol of close protection. Kingsmith had told him he had saved his life, but the details were private. Sean admired him for not turning it into a drinking anecdote.

He stared down at the ice cap, filling up on its peculiar charge of beauty and fear. Today it was glittering white velvet, strewn with lozenges of emerald and turquoise lakes. He did not remember so many of them, nor the line of five white radomes on a plateau of tundra. They had not been there the last time he was here.

‘Indian,’ said Danny Long, in answer to his unspoken question. ‘In the last year. Over on Barentsoya there’s another new construction going on. Telecom, or meteorology.’ The pilot smiled. ‘Improving our broadband.’

‘Good broadband is a valuable asset.’

‘Indeed, sir.’

Sean did not speak again until they were over Hinlopenstreten, where a convoy of cruise ships made white dashes on the dark water. He remembered Kingsmith’s admonition about his friend in Oslo.

‘Have there been many ships in Midgardfjorden? Before that one?’

Danny Long shook his head.

‘Sometimes they stop at the mouth – for photographs, I believe. Then they go round the other way. But the Vanir came right down deep. When it all went off on the radio – not the calving, when they went out and confirmed it was a body – the coastguard were close across at Freyasundet, in that new fast boat of theirs.’

‘Joe said they held it as a crime scene.’ Sean kept his tone neutral.

‘They did, sir, but they told me and Terry not to worry about the words, it was just so they could take all the phones and such from the passengers. Then we were ordered to stand down – return to the Lodge – by the coastguard. So that’s what we did.’ He paused. ‘We had Mr Kingsmith’s guests to look after.’

‘And what did you tell them?’

‘Facts, sir: a body had been recovered from the water. They didn’t know anything until they came down for breakfast. The coastguard had gone by then.’

‘How were they? The coastguard.’

‘Very polite, sir, as always. It was Inspector Brovang, he was out on their new boat, that’s why he was in the area.’

Sean imagined the heavy medevac cradle swinging in the air, trails of water falling behind. Tom’s dead body netted and trussed beneath a helicopter, as high as he was now. Less than forty-eight hours ago.

He put his right hand under his left armpit and pressed down on it. The tingling had come back. Nothing physically wrong with his hand, no nerve damage. Brovang had saved it, with his own body heat. He had taken Sean’s statement as he recovered in the Sickehaus in Longyearbyen, but they had not spoken since that time. Nor had he taken up the standing invitation to either visit Midgard Lodge with guests, or any of Sean Cawson’s other clubs around the world, though he had declined courteously. Sean cancelled out the obscure bad feeling that gave him, with a large annual donation to the children’s charity which Brovang supported and mentioned on his Facebook page. Brovang had never accepted his Friend request.

‘Well, at least he had all the details. He didn’t want to speak to the visitors?’

‘No, he was keen to get going.’

‘Who exactly are they?’

‘Excuse me, sir, I’m not good at names, especially foreign ones. Faces, I never forget. But you can meet them, they’re still at the Lodge.’ He banked the Dauphin over the great crumpled blue-white sweep of a glacier – that stopped short of where Sean’s eye expected it to turn.

He must have misremembered the glacier, it could not have retreated so far in a year and a half. Everything seemed different. ‘Danny,’ he said, ‘remember something: Midgard Lodge is my company and I am your CEO. Not Joe. You report to me.’

‘Yes, sir. I know. I made a mistake. I should have informed you first.’

‘Good, then we’re sorted. How’s everything else?’

‘All good, sir. I was in town a week before the Tata-Tesla retreat, and there were some Russian boys from the new place.’

‘The Pyramiden hotel? Or the one in Barentsburg?’

‘Oh those are long finished, and two more as well. This new one’s called the Arktik Dacha. They were joking with us about it, but in a friendly way. I reckon they’ve had a look at us.’

‘How would they do that?’ Sean’s stomach lurched as they suddenly rose up over the last peaks that pierced the ice cap.

Danny Long grinned. ‘Same way we don’t, at them.’