Читать книгу Sol LeWitt - Lary Bloom - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

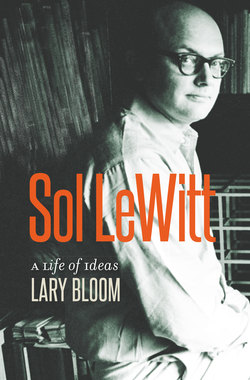

In June 2011, four years after Sol LeWitt’s death, Vanity Fair published a short piece that became a call to biographical action. A photograph showed LeWitt in 1961 in his studio, a rundown heap of a place on Manhattan’s Lower East Side—the neighborhood where he and his circle of rebellious peers tore art down to its basics and started over again. The text beneath the picture was written by Ingrid Sischy, the former editor of Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine:1

Ask any artist who his or her secretly favorite artist is. Chances are the answer will be Sol LeWitt, a pioneer of both minimalism and conceptual art, whose wall drawings, photographs, and sculptures … have a commonsense beauty. When LeWitt died … there was a recognition among art-world insiders that one of the greats had gone, but the commendations were all very quiet—like the man himself. Prediction: Time will bring LeWitt the broader accolades that are his due … LeWitt was everything we expect of an artist but all too rarely get these days: stubborn, generous, iconoclastic, uninterested in money—other than giving it away to help other artists—suspicious of power, and as visionary as anyone who ever made art.2

Paradox is at work here. Reflecting its title, Vanity Fair lavishes attention on those who seek it, not on people such as LeWitt who avoid the limelight. In this case, though, limelight avoidance is what landed the artist on the magazine’s pages. Indeed, LeWitt himself created the primary obstacle to the level of recognition that Sischy argues he deserves.

The Connecticut native left us at least two contradictory legacies: a radiant body of work and a faint self-portrait. The latter—his refusal to participate in the culture of celebrity—is the source of Sischy’s premise. The market for contemporary art benefits from public awareness of artists’ personalities and intimacies. In the case of LeWitt, though most fans know of his revolutionary campaign to change the definition of art, few know anything about his private life (or how it influenced his work) or could have picked him out in a crowded gallery in New York, São Paulo, Sydney, Venice, Düsseldorf, Tokyo, or London.

When the artist attended exhibition openings, he was the quiet and burly fellow in the corner who wore a sport coat with no tie. By choice he was the wallflower, the man with the bald pate whose pleasantly round visage, circular eyeglasses, and tolerant smile hid his distaste for party chatter and art speak. Even at the height of his long career, he never fit the image of the ego-driven artist in need of constant adulation. On party nights, he preferred to stay at home to watch a televised baseball game; read a book of history or philosophy; or listen to one of his more than 4,000 tapes of classical music, jazz, and opera with the volume turned up because of his partial hearing loss. All of that was more attractive than making small talk. As his wife, Carol, once said in regard to his tolerance for public events, “Sol doesn’t do fun.”3

He also didn’t do the rituals of self-aggrandizement. He frustrated photographers and interviewers intent on prying into his life, arguing that it had nothing to do with his art. In the early 1970s, when an Italian magazine asked for a photograph, LeWitt sent a picture of his dog.4 When in his later years he had an opening in Perugia, Italy, and balked at going, one of his assistants took his pooch instead.5 Patrons wanted to know the man behind a reinvention of art making—the Los Angeles Times referred to him as the figure “who changed art internationally”6—but this reinventor, according to the New Yorker’s art critic Peter Schjeldahl, was an artist of “militant anti-personality.”7

LeWitt’s primary impact on contemporary art was his insistence that the role of the artist is that of a thinker instead of a craft master, and that the product of the mind is more significant than that of the hand. The artist’s task, LeWitt argued, is to develop the scope, purpose, and site-specific impact of the work rather than focus on its execution, which he considered “perfunctory.”8 For centuries, it had been the practice of artists, with rare exceptions, to make compositional decisions as they worked. For his major pieces, LeWitt made all decisions before a drop of acrylic paint or an element of sculpture was ever applied. And even then, it was other artists who applied them, not LeWitt. “The idea,” he wrote, “becomes the machine that makes the art.”9 Until his ideas took hold, critics assessed art primarily by examining art as a physical object, not the idea that produced it.10

LeWitt created in the same manner as an architect or composer does, in effect providing only blueprints or scores and hiring multitudes of young artists to finish and install what he had conceived. His oeuvre was vast, consisting of more than 1,250 wall drawings, many of them measured in yards and boldly colored; hundreds of sculptures that he referred to as structures, as a way to demystify art; photography that turned ordinary images into theme-driven statements; an uncountable number of gouaches (because he gave so many away); and books published to promote and distribute the work of colleagues to the general public. In a subjective field like art, there is no reliable way to measure one artist’s output versus another, but the curator Gary Garrels tried in 2000: “LeWitt’s fecundity is staggering. Perhaps not since Picasso has an artist worked with such relentlessness and range.”11

At the same time that he created opportunities and challenges for young artists, he did the same for viewers of contemporary art. For example, through his work on variations on open cubes, he let viewers note the elements that were missing and complete the work in their heads. Cubism had introduced the idea,12 but only in painting and, notably, not using cube shapes.

LeWitt came into his own when the art market began to rival other forms of investment and many artists, particularly the later abstract expressionists and pop art innovators, became media darlings. Some also prospered by branding themselves—doing work over and over again once they had discovered a way to earn money in a competitive art market. LeWitt considered reliance on formula to be lethal to the creative soul. On the effect of market-driven pressures, LeWitt said, “The artist is seen like a producer of commodities, like a factory that turns out refrigerators.”13 Yet by doing things his own way and ceaselessly pushing himself to come up with new ideas that by their nature undermined the idea of branding, he managed to earn millions—and gave a good deal of that fortune away to younger artists and to causes in which he believed.

Following his death from the effects of colon cancer in April 2007, the media focused on his professional achievements and made only sketchy references to anything personal. The obituary in the New York Times called him “a lodestar of American art.”14 Pravda quoted Joanna Marsh, the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art’s curator of contemporary art, who referred to LeWitt as “one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.”15 The Guardian said, “He left in his wake a gaggle of the world’s most ponderous art critics disputing over whether he was a conceptualist or a minimalist or both, while he himself bent his own rules with wiggly lines, irregular geometrical shapes, and even splotches of paint.”16

LeWitt contributed to the confusion. Among his contradictory (and often wry) views was the belief that “it’s not too important what art looks like.”17 He also said that he preferred the kind of art that is “smart enough to be dumb.”18 When given credit for the innovation of wall drawings, he responded, “I think the cave men came first.”19 (The cave men, however, valued permanence, and LeWitt did not.) His sense of humor and highly personal use of words were examples of demystification and the art of the twist: “The wall drawing is a permanent installation, until destroyed,” he said, and “irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically.”20 It seemed at times as if he was the art world’s satirist. When he gave interviews, he punched holes in the usual response script. Asked about the legacy of his native Hartford, Connecticut, a city that had once had a rich cultural identity, he responded, “Everyone is from somewhere.”21 He called out those who relied on art speak, “a secret language that art critics use when communicating with each other through the medium of art magazines.”22

In 1993, the UK critic Rachel Barnes used the term “LeWitticisms” to describe his way of using language to break down barriers.23 The natural enjoyment of art, LeWitt argued, is impeded by critical assessments that are heavy on jargon and short on clarity. He loathed such snobbish and dense interpretation and thought of art as universal: “Every person alive is an artist in some way. The way he thinks or walks or dresses or acts. We’re all making art as we live. You furnish your house the way you want. You arrange your day, if you can, the way you want.”24 About critics, he said: “Artists teach critics what to think. Critics repeat what the artists teach them.” He also commented, “When artists make art they shouldn’t question whether it is permissible to do one thing or another.”25

LeWitt’s playfulness with language sometimes replaced one form of confusion with another, as his logical mind worked out mathematical formulas (even though he insisted he was not particularly interested in math). He typically used the same words as both the title of a work and instructions to the artists who were to complete it. For example, the full title for Wall Drawing #211, created for the Portland (Oregon) Center for Visual Arts in 1973, is: “A line drawn from a point halfway between the midpoint of the left side and a point halfway between the center of the square and midpoint of the left side to a point halfway toward the point where two lines would cross if they were drawn from the center of the square to the midpoint of the top side, and the second line from the point halfway between the midpoint of the left side and the upper left corner to the upper right corner.”26

But the artists he hired to install these pieces understood and were grateful both for the work and for the interest LeWitt took in their own. His crews were largely female, a continuation of his early efforts to encourage many women who challenged the bullies of what was then an overwhelmingly male profession.

Even during his early days as an artistic loner when income was meager, LeWitt promoted the art of colleagues. As time went on and his income grew, he bought or traded pieces for such work, eventually collecting thousands of pieces. He also quietly paid the rent or hospital bills for friends and tuition for their children.

At the same time, he could have made a great deal more money to spend on his many causes had he not stood up to corporate power. Though he insisted his art was not political, it may be argued that the pieces he never undertook had political overtones. He refused major commissions from corporations that offended his liberal views on social justice or that endangered public health.27 All this earned him respect and admiration from fellow artists. The minimalist sculptor Carl Andre spoke for many when he called LeWitt “our Spinoza.”28

LeWitt asserted that objectivity and careful planning yield contemplative art. Hence, his work was often thought to be cold, impersonal, and even anti-art—a sequel, perhaps, to the emperor’s new clothes. Later, however, the public embraced it as deeply personal. Many visitors to his exhibits are stunned by what they see, and children, attracted by the vibrant colors of the huge wall drawings, gasp and stretch their arms wide in delight. As Schjeldahl wrote in 2000, “If his art is without apparent emotion, that just leaves an inviting vacuum. Love rushes in.”29

Contradiction is at the heart of the LeWitt phenomenon and the artist himself, and that became part of my impetus to connect his life and work. The difficulty in making that connection was expressed as early as 1993, when the British art critic Richard Dorment wrote in the Daily Telegraph, “There are few living artists that I admire more than the American Sol LeWitt, and few more difficult to write about.”30

■ My pursuit of the LeWitt story has its roots in the last twenty years of his life. He and I lived in the same small town, Chester, Connecticut. We both belonged to the local synagogue, Congregation Beth Shalom Rodfe Zedek, whose new building he designed,31 and attended Wednesday morning minyan services. On Passover, our families came together to celebrate the holiday and to invite commentary on the bondage and oppression that still persists in the world. Sometimes we read from a Haggadah that I wrote with Marilyn Buel and Jil Nelson—a play in which each person present was given a role. LeWitt was often cast as God. He took the part, though he grumbled about it.

Most often, though, I saw him mornings in his studio. He was always an early riser, so by 9:00 A.M. he had already put in three hours of work and walked with his dog, Lilla, to the middle of town to buy the New York Times, and he could accommodate a visitor—even an unannounced one. Sometimes I watched as he attended to his tasks. Sometimes we sat and talked. He did not use these occasions to complain about the art world or difficulties with his installations. I didn’t use them to express my own professional frustrations at the time, trying to keep Northeast, the Hartford Courant’s Sunday magazine, alive as newspaper economics collapsed, or to discuss the challenges I later faced in the books I was writing. We talked instead about current events, music, and literature. We compared stories about our service in the US Army Quartermaster Corps (LeWitt during the Korean War and me during the Vietnam War). We shared our passions and regrets as two rare Connecticut fans of the Cleveland Indians.32

On a few occasions I couldn’t help asking about his work. In 2005, I saw a pencil sketch pinned to the wall behind his desk. It looked to me like a variation on a series of wall drawings he had recently created, but somehow it seemed a little more complicated, something like interwoven figure eights. “That’s for a ceiling,” he said, “in Reggio Emilia.” I waited for more explanation, but he said only, “Maybe you can see it when you go to Italy this fall.” The work would be installed on the ceiling of the reading room of the city’s eighteenth-century public library. What I didn’t know at the time was that I would view the completed piece before he did. A crew of mostly young Italian artists, following LeWitt’s meticulous instructions, finished Whirls and Twirls that summer.33 I saw it a few weeks later, but LeWitt didn’t learn how his plan worked out until late 2005, when he took his last trip to Italy.34 Several years later, one prominent Italian collector, Giuliano Gori, who had commissioned LeWitt to do site-specific work on his property in Pistoia, referred to Whirls and Twirls as “LeWitt’s Sistine Chapel.”35 However it was labeled, its power had a great effect on me.

As a writer, if I experienced what I called a religious experience—having nothing to do with theism but instead referring to the state of being deeply moved—I inevitably wanted to bring readers into that moment and share that epiphany with them. In the case of Whirls and Twirls, unapologetically bold and colorful and floating above the library patrons below, I thought, “I must write about this.”

But there was more that drove me to write this biography. As I see it, LeWitt transcends categories. Yes, he was a member of an elite group. But with his personal characteristics and the inspiration that resulted from them, he serves as an example for anyone who wants to create—not only painters, sculptors, musicians, and writers, but also teachers, researchers, and entrepreneurs in search of new ideas and techniques and eager to break barriers.

LeWitt once said, “You shouldn’t be a prisoner of your own ideas.”36 This is not a comment limited to art styles. It is instead a call to think freely and honestly every day. Indeed, it is LeWitt’s sense of authenticity in a world of moral complexities and unrepentant egotism that makes his example compelling. A comment he made to the Hartford curator Andrea Miller-Keller seemed to sum up both his ambition and his sense of humility. In response to questions she sent him in Italy in the early 1980s, he said, “I’d like to create something that I wouldn’t be ashamed to show Giotto.”37

His life story, then, should interest anyone who wants to succeed but is afraid of breaking rules. After all, shy and humble Sol LeWitt broke a rule that had held since the Renaissance—that the artist’s hand is the primary force in Western art.38

Many of LeWitt’s peers had, in his view, more natural talent and had grown up without the hardships he had faced. But to him the struggles of childhood and later made his growth as an artist possible. Without struggle, he said, greatness can’t be achieved: “Talent is a curse.”39

Even LeWitt would have agreed, if reluctantly, that his personal decisions and generosity advanced the careers of many colleagues—most significantly, the women he mentored at a time when most female artists were ignored. In part, because of his own questioning, he understood the weight of their pursuits. His support of others also created a financial substitute for the cult of personality, creating momentum through a large circle of artists who promoted each other’s work.

■ The deep friendship between Sol LeWitt and Eva Hesse, as well as the relationship of their respective oeuvres, has lately has been a subject of major art exhibits and film documentaries. Both rejected long-held tenets of art, and Hesse did so within a system that shunned her. When she wrote from Germany that she was at the breaking point, Le-Witt replied. The first half of his long and passionate letter (reprinted in full in chapter 6), with its forty-five consecutive gerunds (many of which would have come as news to Noah Webster), is the part that is often quoted and has even been made into a punk rock video40 and become a performance piece for the actor Benedict Cumberbatch.41

The letter foreshadows the intense adventures in variation (or, as it was generally referred to, seriality) that LeWitt would later pursue, as if he were Johann Sebastian Bach (his favorite composer), not a maker of images. But it is the second half of what he wrote to Hesse, which is almost always missing in commentaries, that underscores the connection between the person making art and art itself. In it, LeWitt refers to his own doubts; like Hesse, he had considered himself an outsider.

LeWitt’s struggle is metaphorical, one that can be understood outside the world of art. For example, in his letter to Hesse he delivered advice in one brief sentence that should serve everyone who yearns for self-discovery and authenticity: “You belong in the most secret part of you.” For him there would be no rut, no “if I could only do what I want to do.” Yet, in this contradictory man, there was another side to him, one that could be cold or dismissive.

As his longtime business manager, Susanna Singer, told me, “Yes, he was an extraordinary man, but Sol was not a saint.”42 I came across lingering resentments in other interviews. As his conceptual colleague, Lawrence Weiner, said in the documentary film Sol LeWitt, made by the Danish director Chris Teerink and released in 2012, “Art is made by human beings, not machines,” and therefore is subject to all human frailties.43 Scholars certainly would point out that, in regard to notable achievers, image and reality are often at odds. One might even cite a line from Tom Stoppard’s Travesties in which the characters clash over art’s meaning, and one of them remarks cynically, “The idea of the artist as a special kind of human being is art’s greatest achievement.”44 Yet in the case of LeWitt, the adoration of colleagues seems not only lavish but genuine.

Some of LeWitt’s frailties, to be sure, came to the fore in his romantic relationships, most significantly in his very brief first marriage. And the artist offered an unsparing self-assessment to one of his lovers, referring to himself as “old, bald, deaf, fat, pig-headed, clumsy and at times self-absorbed.”45 Yet he attracted as romantic partners some of the most accomplished women in Europe and the United States. And though much has been written about the deep friendship between Le-Witt and Hesse and his influence on her work, nothing has been published that makes any significant reference to his many love interests or how they affected him.

To be sure, dozens of exhibition catalogues in a variety of languages about his work contain scholarship and ruminations about key issues of modern art. LeWitt’s own writings and interviews illuminate a great number of key points about the process of making art in the modern age. But the human element makes only cameo appearances.

I subscribe in this biography to the idea I have always practiced as an editor and writer—that is, to humanize subjects and articulate the personal stakes involved in their pursuits, an approach that can make even the most arcane subjects accessible and compelling to readers.

In the case of a man at the center of a complex art revolution, such an approach seems indispensable. The critic Robert Rosenblum began his 1978 Museum of Modern Art catalogue essay for LeWitt’s first retrospective this way: “Conceptual Art? The very sound of those words has chilled away and confused spectators who wonder just what, in fact, this art could be about or whether it’s even visible.” Rosenblum also wrote, “LeWitt’s art may be steeped in his cerebral, verbal and geometric systems, as was that of so many great, as well as inconsequential, artists before him, but his impact is not reducible to words.”46

But what is reducible to words is a story of obstacle and triumph. The artist, after all, led a purposeful and generous life. He overcame setbacks and doubt—phenomena that are nearly universal—and he mastered the delicate balance of sticking to his principles while using flexibility to his advantage. Sometimes, however, the line between sticking to principles and flexibility seemed blurred.

You will read in chapter 14 about LeWitt’s seventieth birthday celebration, an event he didn’t want to attend. That night at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, stunned guests watched as the guest of honor did all he could to ruin the party. During the low point of the evening, when the artist sabotaged the planned tributes, most invitees didn’t know whether to laugh, be outraged, admire the man’s singular personality, or feign concentration on their strawberry dacquoises.

Afterward Carol said to me, “You’ve got to write about this.” However, I hadn’t attended the event in my professional capacity at the time (as editor and columnist). Nonetheless, what had just happened ranked with other significant events in the history of America’s oldest public art museum.

So I wrote a draft piece on the party and called LeWitt to tell him I had done so. His response was gruffly authentic: “Why?” I replied, “Well, I had the instinct to do so,” thinking that the word “instinct” might resonate with him. But then he asked, “Do you always follow your instincts?” I thought that was an odd question, coming from a man who had a reputation for doing just that. Perhaps sensing that the question was full of irony, he changed his approach: “Well, if you’ve written it, the least I could do is read it.” I didn’t mention that journalism ethics discourage giving subjects of pieces access to advance copies to protect the work’s integrity. But as it seemed unlikely that the column would ever run, considering LeWitt’s outrage over it, what was the harm in showing it? I went to his studio the next morning and delivered the piece. He said he would read it in due course.

Days later, having by then embarked on a trip to Israel, I discussed the matter with our rabbi, Doug Sagal. Though much younger than Le-Witt and me, Sagal was widely respected for his wisdom. At the time of our conversation, we were in Jerusalem, in the midst of a congregational tour (the LeWitts were not among the group). Sagal and I had a private moment in the hotel lobby, and I explained the background of the seventieth birthday piece and that I was wrestling with competing forces. He was silent for a moment and looked out of the window in contemplation, in the way that rabbis do. Then he turned to me and said, “Well, maybe you will publish the piece. When the right time comes.” I knew what he meant.

When I next saw LeWitt several weeks later, he asked, “Are you going to run that story you wrote?”

I said, “No, I don’t think so.”

He replied, “Why not? I thought it was pretty good.”

Welcome, then, to the world of Sol LeWitt.