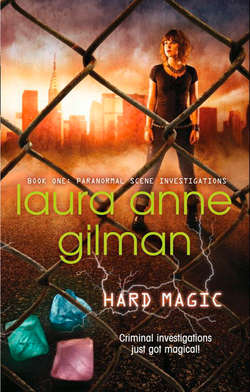

Читать книгу Hard Magic - Laura Anne Gilman - Страница 9

one

ОглавлениеThe dream was back. It always came back when I was stressed.

The site was deserted; I sneaked through the fence and into the house. Lucky for me the alarms hadn’t been turned on yet.

As usual, my brain was telling me that it was only a memory; that I already knew what I would find, that it was okay for my heart to stop pounding so fast, but the dream was in control.

The door called to me. I could feel it, practically singing in the rain-filled dusk. My flashlight skittered across the floor, allowing me to pick my way around piles of trash and debris. No tools left out; the carpenter’s daughter approved.

“Hello, beauty,” I said to the door. Or maybe to the woman in the door: in the darkness, in the beam of light, she was nakedly apparent now, a sweet-eyed woman who gazed out into the bare bones of the room with approval and fondness.

Even now, the beauty of Zaki’s work astounded me, and I mourned again for that loss.

“Who are you, then? That’s the key to all this. Who are you?”

The door, not too surprisingly, didn’t answer. But I knew how to make it talk.

Or I thought I did, anyway.

It was all instinct, but J had always told me that instinct was the way most new things were discovered—instinct and panic.

I held my hand over the door the way I had with the tools, carefully not making physical contact with it, and touched just the lightest levels of current, like alto bells sounding in the distance.

The woman’s hair stirred in a breeze, and her face seemed softer, rounder, then she disappeared behind the leaves again.

I hated her, this woman I’d never known, never met. Hated her for being the reason my father was dead.

Zaki really had been an artist, the bastard. I could feel him in the work. But I didn’t know, yet, what he had been feeling.

*evidence doesn’t lie*

Shut up, I told the voice. I’m working.

I touched a deeper level of current, bringing it out with a firm hand and splaying it gently across the door so that it landed easily, smoothly.

Oh, how I love her, such a bad woman, such a wrong woman, and I cannot have her, but I will show her my love….

Zaki, melancholy and impassioned, his hand steady on the chisel, his eyes on the wood, sensing even through his distraction how to chip here, cut there, to make the most of the grain. He was concentrating, thinking of his object of affection, the muse who inspired him.So focused, the way all Talent learned to be, that he never saw the man coming up behind him, the man who had already seen the work in progress, and recognized, the way a man might, the face growing out of the wood.

I knew what was about to happen, in my dream-mind, and tensed against the memory.

The blow was sudden and sharp, and the vision faded.

No, I told my current. More.

It surged, searched, and found…nothing. No emotions from the killer. No residue of his actions. It had been too long, or he had been too good, too quick. Or I needed to be better, sharper.

You were a kid, I wanted to tell my then-self. You did what you could, and you did as well as you could. But you can’t talk back to memories, only relive them.

“Damn it.” My flashlight’s beam dropped off the door; I was unwilling to look at the face of the woman who had cost my father his life.

*there is always evidence*

The voice was back. And probably right. I let the beam play on the floor, unsure what I was looking for. Scan, step, scan. I repeated the process all the way up to the door, then turned around and looked the way I had come.

“There.”

On the floor, about two feet away. A spot where the hardwood floor shone differently That meant that it had been refinished more recently than the rest of the floor, or been treated somehow…. Zaki would have known. All I knew was that it was a clue.

I touched it with current, as lightly as I could. Something warned me that a gentle touch would reveal more than demanding ever would.

“The killer’s actions, I beg you wood, reveal.”

J’s influence: treat current the way you would a horse; control it through its natural instincts. Current, like electricity, illuminated.

A dent in the floor, sanded down and covered up. The point of a chisel stained with blood? No. The harder end, sticking out of a body as it landed, falling backward …

Oh, Zaki, you idiot was all I could find inside myself, following the arc of the body. For a woman? For another man’s woman when you had Claire at home?

And then I saw it, the shadow figure of the killer, indistinct even in his own mind—shading himself. That meant the killer was a Talent, if of even less skill than Zaki. Had that been a factor? The man—the foreman, I knew now—jealous not only of the carpenter’s attraction to his wife, but of his skill to display it, driven to murder?

The chisel was removed, wiped down, and …

I still flinched, even years and dreams later.

The blood alone flared bright in the pictorial, a shine of wet rubies in the shadows as the foreman dipped the chisel into a cloth still damp with the blood, laying the trace for me to find, a week later.

Find, and be unable to do anything about, save live with the knowledge that my father had been murdered, and the murderer still walked, unpunished ….

I woke up, and the still-powerful sadness of dream faded, although it never really went away. Zaki had been dead for three years, though, and I’d learned to live with it. My depressing reality was more immediate: three months out of college, and I still didn’t have a job.

I thought about putting the feather pillow over my face until I turned a proper shade of blue and suffocated. Even knowing that it was the overblown act of a spoiled five-year-old didn’t stop me from contemplating it, running through scenarios of who would find me and what they might say or think or do. Eventually, though, I shoved the pillow to the side and stared glumly up at the ceiling.

No, I wasn’t quite that desperate. But it was close.

Nobody wanted to hire me. It wasn’t that I didn’t have brains. Or enthusiasm. Or dedication, for that matter. I just … didn’t know what to do with any of what I had. I guess that was showing up in my interviews, because nobody was saying “welcome aboard.”

Something had to break soon, or I was looking at a short-term career goal of flipping burgers or, if I was lucky, pulling beers at a semidecent pickup bar.

“Oh, the hell with that.” I got out of bed and stripped down my sweat-soaked T-shirt and panties, replacing them with my sweat-dried gym clothes, fresh socks, and my sneakers, and headed down to the hotel’s gym. The only way to interrupt a self-pity party was with a good hard run.

I got back to my room, feeling only a little bit better, just in time to take possession of my breakfast order. I let the room-service guy in and tipped him, the door barely closing behind his back when the phone rang. I dropped the receipt on the table and picked up the phone, telling myself not to make any assumptions or unfounded leaps of hope. This early, though, it might be good news. Did people really call at 9:00 a.m. with bad news? Didn’t they put that off as long as possible? “Bonita Torres.”

“Ms. Torres? This is Sally Marin, at Homefront Services.”

I could tell by the sound of her voice that the news wasn’t going to be good. Damn. Deep breathing is supposed to be good for panic, wasn’t it? I took a breath, held it, and then let it out. Nope, didn’t help.

I shifted the phone to the other ear, and tried to relax my shoulders, kicking off my sneakers and peeling off my socks. There was no reason to panic. My checkbook was still decently in the black, I wasn’t in debt, if you could ignore a credit card or three coming due at the end of the month, and I had a degree from a top school packed with all my belongings in storage while I lounged around in a swank little suite on the Upper East side of Manhattan on a lovely, not-too-hot summer day.

Life could be worse, right?

Life could be a hell of a lot worse. I knew that firsthand. I took another deep breath and stared at my feet—I’d painted the toenails dark blue, to keep myself from thinking about the demure pale pink that was on my fingernails—and wiggled them. Yeah, things could be worse. But they could be shitloads better, too.

The brutal truth of the matter was that I needed a job, and not a minimum-wage one, either. Joseph kept telling me to relax, that I’d find something, but much as I love J, and he loves me, I couldn’t mooch off him for the rest of my life, letting him pay for this hotel, my food, and my clothing. Sure, he had money but that wasn’t the point. Comes a time, you’ve got to do for yourself, or self-esteem, what’s that?

The problem was, J’s been doing for me for so long, I think we’ve both forgotten how for him not to. Not that he spoiled me or anything, just … He’s always taken care of me. Ever since I was eight years old, and an instinctive cry for help had literally pulled him off the street and into my life.

The dream came back to me, and I shoved it away. My dad, rest his soul, always meant well, and I’d never had a moment’s doubt that he loved me, but Zaki Torres had been a crap parental figure, and his decisions weren’t always the best even for himself, much less me. J had taken one look that day, and arranged to become mentor to that mouthy, opinionated eight-year-old. He taught me everything I needed to know and a bunch of stuff he figured I’d want to know, and then, ten years later, had the grace and wisdom to let me go.

Not that I went far—just off to college for four years. But even then, J was there, the comforting shadow and sounding board at my elbow, not to mention the tuition check in the mail. Now that phase was over, and it was time to be an adult.

Somehow.

And that was why I was starting to panic.

“I’m sorry, Ms. Torres,” the woman on the other end of the phone line was saying. “Your résumé was quite good, of course, but … “

I kinda tuned her out at that point. It was the same thing everyone had been saying for the past three months. I’m smart, I’m well educated—the aforementioned four years at Amherst will do that—and I’m a hard worker. All my references were heavy on that point. I’ve never shied away from a challenge.

Only these days, nobody wanted to hire someone with a liberal-arts degree and minimal tech skills, no matter how dedicated they might be.

It wasn’t my fault, not really. I know how to use computers and all that. It’s just that I can’t. Or, I can, but it doesn’t always end well.

I’m a Talent, which is the politically correct way of saying magic user. Magician. Witch. Whatever. Using current—the magical energy that floats around the world—is as natural to me as hailing a cab is to New Yorkers. Only problem is, current runs in the same time-space whatever as electricity, and like two cats in the same household, they don’t always get along. They’re pretty evenly balanced in terms of power and availability, but current’s got the added kick of people dipping in and out, which makes it less predictable, more volatile. Which means a Talent … well, let’s just say that most of us don’t carry cell phones or PDAs on our person, or work with any delicate or highly calibrated technology.

I’m actually better than most—for some reason my current tends to run cool, not hot, meaning I don’t have as many spikes in my—hypothetical—graph. Nobody’s been able to explain it, except to say I’m just naturally laid-back. I guess it’s because of that I’ve never killed a landline, or any of the basic household appliances just by proximity the way most Talent do, but there’s always the risk.

Especially when we’re under stress. You learn to work around it, and I wouldn’t give up what I am, not for anything, but sometimes current is less a gift and more a righteous pain in the patoot. Especially when you’re trying to find a job in the Null world.

Ms. Marin had finished making apologies, finally.

“Yes, thank you. I do appreciate your taking the time to speak with me.” J taught me manners, too. I hung up the phone, and stared at my toes again. The sweat of my treadmill workout seemed far away, and the dream-sweat closer to my skin, somehow.

Damn it. I had really hoped something would come out of that interview. Something good, I meant.

Lacking any other idea or direction, I wandered over to the desk, where a pile of résumés, a notepad, and my breakfast—a three-egg omelet with hash browns and ketchup—waited for me to get my act together. There were still half a dozen places I needed to call, to follow up on applications and first interviews. I sat in the chair and stared at the notepad, with its neatly printed list—the result of ten weeks of intensive job-hunting—and felt a headache starting to creep up on me. At this rate, I really was going to be begging for temp jobs or—god help me—going back to retail. My life’s ambition, not really. I might not know what I wanted to do, but I knew what I didn’t want.

I forked up a bit of the omelet and took a bite, less because I was hungry and more because it was there. Other Talent found their niche, why couldn’t I? All right, so a lot of them became artists, or lawyers, or ran their own companies, where their weirdness wasn’t noticed, or was overlooked. None of that really interested me, even if I’d had an inch of artistic or entrepreneurial talent, which I didn’t. Academia maybe, but the truth was that while I loved learning, school mostly bored me.

Me bored was a bad idea. When I was bored I did things like create a spell that would burn out selected letters in neon signs all over town, until it looked as though there was a conspiracy against the letters Y and N. Listening to people’s crackpot theories about what had really happened for the rest of the week had been fun, but …

But I needed something to do.

They say you should follow your interests, go for what you’re passionate about. To do something that mattered would be nice. I needed to be able to get my teeth into something, to feel that it was worthwhile. Other than that … I didn’t know. I guess that works if you’ve got some kind of artistic talent, or want to make the world a better place, or have an isotope named for you. Me, not so much.

There had been a while, after Zaki’s murder, when I’d thought about going into law enforcement, but it was tougher these days for Talent to make it—less shoe leather and more high-tech toys. I might make it through the Academy, but spending the rest of my life pounding the pavement, unable to advance, didn’t thrill me. And J was even less happy with the idea. He wanted me in a nice, safe office. Preferably a corner office, with an assistant to handle the heavy lifting and typing.

I scowled at the list again. Three advertising agencies, two trade magazines, and a legal aid firm. That was all I had left.

“Screw it. Shower first.” Whatever the cause, I was sticky and sweaty, and my hair was kind of gross. Maybe washing it would get my brain going.

The bathroom was reasonably luxe, with scented shampoos and conditioners and soaps, and I took my time. I thought I heard the phone ring, but since I was soaking wet and had just lathered up, I ignored it. This place wasn’t quite pretentious enough to rate a telephone in the bathroom. I’m not sure J would have let me stay here if there had been one—he’s sort of old-fashioned and genteel, and things like taking a phone call while you’re on the crapper would give him frothing fits.

The thought, I admit, made me giggle, even in my depression. J is such a gentleman in a lot of ways, old school, and yet he kept up with me pretty well. I wonder sometimes what crimes he committed as a young’un, that he was the one to be landed with me.

Far as I could tell, his only mistake had involved being in the wrong place at the right time. Zaki had enough sense to know he wasn’t a strong enough Talent, and didn’t have enough patience to mentor me, but his first choice was a disaster waiting to happen, and even as a kid I knew that the moment he introduced us. The guy was … well, he wouldn’t have sold me to pay off his gambling debts, but I wouldn’t have learned a whole lot, either.

The moment was still crystal-sharp in my memory: Zaki’s worried presence, hovering; Billy’s pleasure at being asked to mentor someone for the first time in his life; the smell of a freshly washed carpet that didn’t hide the years of wear and tear …

With an amazing lack of tact that still dogs me, I’d used my untrained, just-developing current to yelp for help. That had attracted the attention of a passerby on the street below, who—despite having already done his time as a mentor, and being way out of our league—came up the stairs, took one look, and took on the job.

Zaki had been lonejack, part of the officially unofficial, intentionally unorganized population of Talent. J was Council—the epitome of structural organization. Despite that, they both got along pretty well, I guess because of me. I wasn’t the only lonejack kid mentored by a Council member, but I was the only one we knew of who stayed at least nominally a lonejack.

“Maybe if you’d crossed the river, you’d have had a job offer waiting for you when you graduated,” I grumbled. “Why do you insist on thinking that nepotism’s a dirty word?”

Truth was, I didn’t think of myself as either one group or the other, and maybe that was part of the problem. Born to one magical community, raised in another, Latina by birth and European by training, female imprinted on a—oh god, use the word—metrosexual male … Issues? I probably should have subscriptions at this point.

My hair’s short enough that it doesn’t take long to wash, and by the time I got out of the bathroom, toweled off, and wrapped in one of the complimentary bathrobes, the strands were almost dry. I’m a natural honey-blonde, thanks to my unknown and long-gone mother, but it hasn’t been that shade since I was fourteen—I was currently sporting a dark red dye job that I had thought would look more office-appropriate. So much for that thought doing me any good. Maybe I’d go back to purple, and the hell with it.

Contemplating an interviewer’s reaction to that, I walked to the bedroom, and saw that the light on the phone was blinking. Right, the call I’d missed. Whoever called, they’d left me a message.

My heart did a little scatter-jump, and my inner current flared in anticipation, making me instinctively take a step away from the phone, rather than toward it. Normally, like I said, my current’s cold and calm, especially compared to most of my peers, but I’d been out of sorts recently, and wasn’t quite sure what might happen. Bad form to short out your only means of communicating with potential employers. Plus, the hotel would be pissed, and complain to J.

Once I felt my current settle back down, I let myself look at the blinking light again. You could call first thing in the morning with bad news. Okay. You didn’t call and leave a message with bad news, did you? I didn’t know. Maybe. Just because everyone seemed eager to tell me no to my face didn’t mean that was the only way to do it.

All right, this was me, keeping calm. Hitting the replay button. Stepping back, out of—hopefully—accidental current-splash range …

“This message is for Bonita Torres. Two o’clock tomorrow afternoon.” The speaker gave an address that I didn’t recognize, not that I knew damn-all about New York City, once you get past the basic tourist spots. “Take the 1 train to 125. Be on time.”

No name, no indication of where they got my name or number, just that message, in a deep male voice.

An interesting voice, that. Not radio-announcer smooth, but … interesting.

Someone smart would have deleted the message. Someone with actual prospects would have laughed and said no way.

I’ve always been a sucker for interesting.