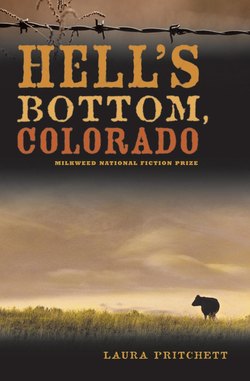

Читать книгу Hell's Bottom, Colorado - Laura Pritchett - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSUMMER FLOOD

LEX IS BACK IN town. This is why, no doubt, Carolyn has been dreaming of him, of his hands sliding into her jeans, insistent, pushing their bodies together.

These dreams are simply her way of working through her fears, her understanding that she is growing older. She knows this. She knows that she misses that falling-in-love love, the first time someone leans forward and oh, God, demands a kiss kind of love.

As she lies next to her husband, whom she really does love, she dreams of her old boyfriend reaching out for her. She is young and he is young, and the intensity that comes from youth and desire fills her pelvis and her heart. She wakes throbbing with the knowledge she is both in love and loved intensely. Then the pang of waking, of finding Del beside her. She is filled with an odd intense yearning, the kind of pain that refuses to dissipate, even now in the afternoon sun.

She’s sitting in a lawn chair, watching the knife in her hand as it slices through the white meat of an apple. These are the tart and bruised apples from the tree beside her, the ones with worms, the ones partly rotted. She refuses to let them waste. Instead she slices them, scatters the thin pieces across baking sheets, lets them dry in the sun. This winter she’ll feed them to the horses as a treat. She promises herself this: in a few months, when she walks out to break the ice on the stock tank and greets the horses, she’ll hold out a handful of withered apple slices in the palm of her gloved hand and remember this day and what it is to be warm, and remember this ache pulsing through her body.

She hopes that by then, the dreams will be gone, along with the heat of summer. The dreams are only a phase, after all, simple enough to dissect and understand. She stops to look up at the mountains and asks herself, quite gently, to quit these dreams. Then she grows a little angry and scolds herself for this self-made torment night after night, these visions that make no sense.

She picks up another apple from the pile beside her lawn chair and slices it into a big bowl that’s balanced on her tanned knees. At the same time her son, Jack, and his girlfriend, Winnie, gallop up to the edge of the fence that separates the lawn from the field.

“Watch us,” Jack shouts at her. He and Winnie look flushed and bright from riding, and the horses are lathered slick with sweat.

“Go help your father,” she says, pretending to ignore them.

“Ah,” Jack says, waving her comment away with his hand. “Watch us first.”

“Hey, Carolyn,” says Winnie. “You’re getting burnt.”

“I know it,” she says, looking down at her arms. They feel tight with the sunburn of yesterday, and today will only add to it. The heat is pouring down and seeping into her skin. She pulls her shirt away from her damp skin and holds it out, hoping for a breeze to waft in and touch her belly. The shirt is her daughter’s black tank top, pulled from the laundry this morning. The day is too hot for a shirt, too hot for black. If the kids weren’t around, she’d think about pulling the shirt off and working topless, and this makes her smile, the image of herself in this lawn chair, slicing apples, wearing no top.

“Are you watching?” Jack demands. “Are you going to watch?”

She stabs the knife into the apple and sets it on the wooden armrest of the lawn chair. “I’m watching,” she says.

“Stand up so you can see better,” he says.