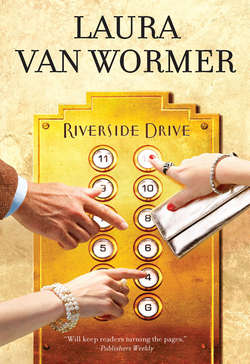

Читать книгу Riverside Drive - Laura Wormer Van - Страница 9

1

ОглавлениеThe Cochrans have a party

Cassy Cochran was upset.

Michael, her husband, had gone to pick up ice four hours ago and hadn’t been seen since; Henry, her son, was supposed to be back from Shea Stadium but wasn’t; and Rosanne, the cleaning woman, was currently threatening the new bartender in the kitchen with deportation proceedings if he didn’t see her way of doing things.

Not a terrific beginning for a party that Cassy absolutely did not want to have.

“Hey, Mrs. C?” It was Rosanne, standing in the doorway to the living room.

Cassy turned.

“If Mr. C comes back, he’s gonna be pretty upset about how this guy’s settin’ up the bar. Could you—” She frowned suddenly and leaned her head back into the kitchen. “What?” she said. “Well, it’s about time.” Rosanne swung back around the doorway, waving her hand. “Never mind, Mrs. C, Mr. Moscow here suddenly understands English.”

Cassy smiled, shaking her head slightly, and then surveyed the living room. It was a very large, very airy room that, in truth, almost anything would look marvelous in. And Cassy’s taste for antiques (or “early attic,” as Michael described her preference) was especially fitting, seeing as every floorboard in the apartment creaked. But then, the apartment was really much more like a house, a big old country farmhouse, only with high ceilings. And windows. The three largest rooms—the living room, the master bedroom and Henry’s room—all had huge windows facing out on the Hudson River.

The windows had been washed this week. Before, shrouded in a misty gray, the view from the twelfth floor had been eerily reminiscent of London on what Henry called a Sherlock Holmes kind of day. But no, this was New York; and the winter’s soot had all been washed away and the late afternoon April sun, setting across the river in New Jersey, was, at this moment, flooding the living room with gentle light.

For a woman from the Midwest, the view from the Cochrans’ apartment never failed to slightly astonish Cassy. This was New York City? That steely, horrid, ugly place that her mother had warned her about? No, no…Mother had been wrong. Hmmm. Mother had been right about many things, but no, not about New York. Not here. Not the place the Cochrans had made their home.

Sometimes the view made Cassy long to cry. The feeling—whatever it was—would start deep in her chest, slowly rise to her throat and then catch there, hurting her, Cassy unable to bring it up or to press it back down from where it had come. She was feeling that now, holding on to the sash of the middle window, looking out, her forehead resting against the glass.

The Cochrans lived at 162 Riverside Drive, on the north corner of 88th Street. Looking down from the window, Cassy’s eyes crossed over the Drive to the promenade that marked the edge of Riverside Park. The promenade was arbored by maple, oak and elm trees, underneath which, across from the Cochrans’, were a line of cannons from the Revolutionary War, still aimed out toward unseen enemy ships. To the right, up a block, was the gigantic stone terrace around the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, a circular, pillared tower patterned after the monument of Lysicrates in Athens. But this part of Riverside Drive was built on a major bluff, and it was beneath it that lay the heart of the park’s glory.

Acre upon acre of the park was coming alive under the touch of spring, the trees bursting with new leaves, the dog-woods and magnolias flowering their most precious best. From here, too, Cassy could look down and see the community garden; in a month it would be one long sea of flowers, flowing down through a valley of green.

Traveling down the slope of the park, Cassy’s eyes, out of habit, skipped over the West Side Highway and down to the walkway by the river’s edge. It was green there, too. And then, down there, the Hudson River. Lord, she was beautiful.

It was the river that always played with Cassy’s heart. There were days when Cassy looked out and thought to herself, How does she know? She would be as dark and gray and cold as Cassy felt inside. But then there were those days when the river was as blue and as dazzling as Cassy’s own eyes were. Oh, how awful it was on those days when Cassy’s heart was cold and dark, and the river was so beautiful. Like now. How does she do it? Cassy wondered. The river had all of these crazy New Yorkers on one side of her, and all of these crazy New Jerseyites on the other, forever throwing rocks and trash at her, dumping things in her, and, sometimes, even throwing themselves into her in an effort to get this thing called life over with. And yet…her tides continued to ebb and flow, and the winds continued to blow across her, and her rhythms of regeneration went on, pulling, pulling downward, her glorious expanse gracing the urban landscape, pulling, pulling downward, spending herself, finally, totally, into the relentless mouth of New York Harbor.

Cassy sighed.

“You okay?”

Cassy pressed the bridge of her nose for a moment and then turned around. “I’m fine,” she said. And then she smiled at Rosanne. And then she laughed.

“What?” Rosanne said.

“Well,” Cassy began, pausing, touching at her earring.

Rosanne’s eyes narrowed slightly.

Cassy glanced at her watch and then back to Rosanne. Back to the “Cooperstown Baseball Hall of Fame” bandanna that was slipping down over Rosanne’s eyes. Back to Rosanne’s blue denim shirt, whose shirttail was hanging down to her knees. Back to her jeans, whose hem lay in folds around the top of her Adidases. Back to thin little Rosanne, all five feet of her, standing there, just waiting for Cassy to say it.

Cassy moved forward toward her. “It’s time for you to change,” she said, smiling.

Rosanne looked to the ceiling. “Here we go,” she said. “Ya know, Mrs. C,” she continued, as Cassy took her by the elbow and steered her toward the kitchen, “you never said nothin’ about me havin’ to play dress-up.”

They were in the kitchen now, and Cassy stopped, looking back at Rosanne. She smiled, yanked the bandanna down over Rosanne’s eyes and turned to the bartender. “Have everything you need, Ivor?”

“Yes, Madame Coch-ah-ren,” he replied, bowing slightly.

“Good,” she said, pulling Rosanne along through the kitchen to the back hall. Rosanne scooped up her bag from the counter along the way.

“And I never said I was a caterer,” Rosanne reminded her.

“Right,” Cassy said.

“So I don’t know why you get so picky about what I wear—it’s not as if you like any of these guys.”

They were in the master bedroom now, and Cassy headed toward her closet. “I think you’re going to like it,” she said, opening the doors.

“Mrs. C,” Rosanne said, throwing her bag on the bed, “ya know, if you’d just tell me, I’d bring one of the ones you already got me.”

“Well, I was in Macy’s and there it was, just hanging there, calling, ‘Rosanne, Rosanne, I was made for Rosanne.’”

Rosanne sighed, pulled off her bandanna and shook out her hair. Cassy turned around, holding a pretty blue and black print dress. “Hair,” she said, “good Lord, Rosanne, you have hair.”

“Come on, Mrs. C,” Rosanne said, turning away.

Cassy walked over and laid the dress out on the bed. She looked at Rosanne a moment and then smiled, gently. “Tell me the truth—do you really hate doing this?”

Rosanne shrugged and proceeded to pull some things out of her bag: a slip, some panty hose and a pair of shoes.

The doorbell rang.

“Uh-oh,” Cassy said, looking at her watch, “somebody’s here already. No, let Ivor get it, Rosanne. You go ahead and get changed.”

Rosanne shrugged again and started undoing the buttons of her shirt while Cassy walked back to stand in front of the closet door mirror. She scanned it. A few wisps of blond hair were already falling out of the clip. But her eyes were still blue. Her nose was still perfect. Her mouth still had lipstick. Body was still tall and slim. Bracelets, check. Earrings, check.

Cassy was still beautiful. Cassy was still forty-one. She would not stand closer to the mirror than she was; she would not care to see the reminders of her age showing around her eyes, mouth and neck.

“Don’t know how good Mr. Moscow’s gonna be at greetin’ guests,” Rosanne said.

“Hmmm,” Cassy said, raising her chin slightly, still looking at herself in the mirror.

“And you don’t want to scare him right off the bat,” Rosanne continued.

Cassy laughed.

“They said he was the last bartender they’d send us,” she reminded her.

“Oh, Lord, that’s right.” Cassy closed the closet door and sailed out of the bedroom, down the hall and through the kitchen to the front hall, where she found Ivor standing in front of the open door. “Who is it, Ivor?” When he gave her a vacant look, she stepped forward to peer around his shoulder. “Oh, Amos. Hi.”

“Hi,” Amos Franklin said. Both Ivor’s and Cassy’s eyes were fixed on the stuffed head of an unidentifiable animal that was snarling on top of Amos’ head.

“It’s okay, Ivor,” Cassy said, patting the arm with which Ivor was blocking the door.

Ivor did not seem convinced.

“He’s a guest,” Cassy told him. “We’re supposed to let him in.” Ivor’s eyes shifted to her. She nodded, smiling encouragement. He took one more look out the door, frowned, and slipped behind Cassy to return to the kitchen. “Sorry about that,” Cassy said, waving Amos in. “I have no idea what I’ve done to earn his protection.”

“Any man would want to protect you,” Amos whispered.

Here we go, Cassy thought. Amos was forever whispering little things like that—that is, when his wife wasn’t around. “Nice hat,” she said, snarling fangs sweeping in past her eyes.

“Michael gave it to me for my birthday,” Amos said. He reached up, groped around, and patted the animal on the nose. “I don’t think it’s real, though.”

Cassy led Amos into the living room, explaining that Michael was out getting some ice.

“Good,” Amos said, sitting on the couch and patting the seat next to him, “it will give me a chance to talk to you.”

Cassy sat down in one of the chairs.

“You’re beautiful.”

“What?”

“You’re beautiful,” Amos repeated.

“Ivor!” Cassy called out. He was there like a shot. “Ivor,” Cassy directed, “ask Mr. Franklin what he would like to drink.”

Ivor stared at him.

“Scotch on the rocks,” Amos said.

Ivor moved over to Cassy. Bowing, “Madame?”

“A Perrier with lime, please. Thank you, Ivor.”

Ivor took one more look at Amos and departed.

“So, Amos, tell me how you are.”

Amos was not good. As the head writer for Michael’s newsroom at WWKK, he never made a secret of his keen dislike for Michael Cochran. After a minilecture on the abuse and misuse of Amos Franklin at work, he would invariably end up with a pitch for Cassy to hire him at her station, WST. Cassy’s mind wandered, and as Amos progressed with his story about how “a certain egomaniac who will go unnamed” took credit for a job done by “a certain unsung hero who will go unnamed,” Cassy—not for the first time—thought about Michael’s parties.

Once a month Cassy’s husband wanted to have a party. Cassy had never, ever wanted any of these parties, but it wasn’t because she was antisocial. It was because Michael had this thing about only inviting people who seemed to despise him. And too, they—these people who despised Michael—were all professionally dependent on him. And so, whether it was Amos, or a technical director, or a character generator operator, they all came to Michael’s parties and drank with him and laughed with him and despised him. If Cassy made the mistake of trying to talk Michael out of one of these parties he would go ahead and invite the people anyway and then spring it on her the morning of the day it was being held. This was not the case this Sunday evening, however; this party had been announced Friday night. (“Cocktails.” “For how many?” “Ten, fifty maybe.”)

“Have you met the Kansas Kitten yet?” Amos was asking her, taking his drink from Ivor.

Cassy tried to think. “Oh, the new anchor. No, I haven’t. Thanks, Ivor.” He bowed again.

“Alexandra Waring—that wearing woman, we all call her,” Amos said, stirring his drink with his finger. He put the finger in his mouth for several moments and sent a meaningful look to Cassy—who chose to ignore it. Slightly annoyed, Amos continued. “But you know all about Michael’s private coaching lessons.” When she didn’t say anything, he laughed sharply, adding, “Day and night lessons.”

“If Michael brought Alexandra Waring here from Kansas,” Cassy said, rising out of her chair, “then she must be extraordinarily talented. Excuse me, Amos, I have to check on things in the kitchen.”

“Extraordinarily talented,” she heard Amos say. “Too bad we’re not talking about the newsroom.”

In the kitchen, Cassy told Ivor to listen for the doorbell. “And let whoever it is, Ivor, in. All right? Oh—” She retraced her steps. “Take that tray of hors d’oeuvres in, please. And if that animal tries to bite you, you have my permission to kill it.”

Cassy walked back to the bedroom, knocked, and let herself in. Rosanne was standing in front of the mirror—in the dress. She looked terrific and Cassy told her so, moving over to check the fit from a closer view.

“Did Mr. C lose his keys again?”

“No,” Cassy said, turning Rosanne and looking at the hem, “that was Amos.”

“The guy I threw the sponge at last time?”

“Yes. Rosanne, come here.” Cassy pulled her over to the dressing table and sat her down. She picked up her own brush and paused. To Rosanne’s reflection in the mirror she said, “I want to try something with your hair.” Rosanne shrugged. Cassy took it as consent and started to brush out Rosanne’s long hair.

“Too bad you didn’t have a daughter,” Rosanne said into the mirror.

“Hmmm.” Cassy had hairpins in her mouth. She was bringing the sides of Rosanne’s hair back up off her face. The doorbell rang; Rosanne started to rise; Cassy pushed her back down into the chair. “Not yet.”

Rosanne watched her work for a while and then said, “Who did you play dress-up with before me? Not the kid, I hope.” The kid was Henry, Cassy’s sixteen-year-old son.

“No one,” Cassy said. She looked down into the mirror, turning Rosanne’s head slightly. She considered their progress and then met Rosanne’s eyes. “You know, Rosanne,” she said, “the only reason I do this is because you’ll need it one day.” She paused, letting her hand fall on Rosanne’s shoulder. (The doorbell rang again.) “You’re not going to be cleaning houses forever.” Rosanne’s eyes lowered. “Maybe you don’t think so,” Cassy said, resuming brushing, “but I know so. And I want you to be ready.”

Silence.

It wasn’t a lie, what Cassy had said. But it certainly wasn’t the whole truth behind “playin’ dress-up.” The first time Cassy had coaxed Rosanne out of her usual cleaning garb and into a dress, Cassy had been quite taken aback. For some reason Cassy couldn’t understand, Rosanne seemed determined to conceal from the world not only her body but the basic truth of an attractive face. Here, right now, in the mirror, was a nice-looking young woman with long, wavy brown hair, large brown eyes (with lashes to die for) and a slightly Roman nose. And her skin! Twenty-six years of a difficult life, and yet not a mark was to be found on Rosanne’s complexion.

And so the whole truth had a lot to do with Cassy’s pleasure at performing a miracle make-over. And it did seem miraculous to Cassy, this transformation of Rosanne, because she herself always looked the same—at her best. And Cassy longed for a startling transformation for herself, but there was no transformation to be had. No, that was not true. There was one long, painful, startling transformation left to Cassy now—to lose her beauty to age. Others might not have noticed yet but, boy, she had. Every day. Every single day.

“I want you to enjoy what you have while you’ve got it,” Cassy murmured, picking up an eyeliner pencil.

Rosanne made a face in the mirror (decidedly on the demonic side) and then sighed. “Well, if I’m gonna lose it, maybe I don’t wanna get used to havin’ whatever it is you keep sayin’ I got.”

“Youth,” Cassy said, smiling slightly, tilting Rosanne’s face up. “Close your eyes, please.”

“Youth?” Rosanne said, complying with Cassy’s request. “Man, if this is youth, then middle age’ll kill me for sure.”

“I know what you mean,” Cassy said.

The doorbell rang again.

“So you’re on strike, or what?”

“Maybe,” Cassy said. “Hold still.”

Ten minutes later the doorbell rang again and Cassy hurried to reassess and touch up her work. There was a great deal of noise coming from the front of the apartment now, and Cassy hoped that Ivor hadn’t quit yet. “Okay,” she said, stepping back, “that’s it. If I do say so myself, you look wonderful. Here,” she added, handing Rosanne some earrings, “put those on and then come out and make your debut. I better get out there.”

As Cassy reached the door, Rosanne said, “Hey—Mrs. C.”

“Yes?”

Rosanne was admiring herself in the mirror. “Thanks.”

Cassy smiled. “The pleasure’s all mine.” She turned around and nearly collided with a young woman in the hall. Cassy stepped back, profusely excusing herself. The young woman merely laughed.

Who was this?

Looking at Cassy was the most exquisite set of blue-gray eyes she had ever seen. And the eyes were not alone—great eyebrows, good cheekbones, a wide, lovely mouth. And her hair…This wonderfully dark, wildly attractive hair about the woman’s face.

How young you are, Cassy thought.

“You must be Cassy,” the girl said. Her voice was deep, her diction perfect.

Cassy realized the girl was offering her hand to be shaken and so she took it, and did it, still fascinated with her eyes. “Yes,” she said, “and you’re…?”

“Alexandra Waring,” she said, baring a splendid smile.

Cassy apparently jerked her hand away, for the girl took hold of her arm and said, “I’m sorry, did I startle you?”

Oh, Lord, Cassy thought, you may be the one Michael will want to marry. “How old are you?” Cassy said, cringing inside at how ridiculous the question sounded.

“Twenty-eight,” Alexandra said, laughing.

“Well,” Cassy said, clasping her hands together in front of her and composing herself slightly, “Michael has told me a great deal about you.” When the girl merely continued to smile at her, Cassy shrugged and said, “So—don’t you want to ask me how old I am?”

The girl’s smile turned to confusion on that one, and the moment was saved by Rosanne’s head appearing over Cassy’s shoulder. “I saw you in the Daily News,” she said. “Liz Smith says they’re gonna can Boxby to make room for ya.”

“I really don’t know,” Alexandra said vaguely.

“Better read Liz Smith then,” Rosanne suggested.

“Oh, brother!” cried a booming voice. It was Michael, his six-foot-two frame looming from the other end of the hallway. Cassy could already tell that he was three—no, maybe only two—sheets to the wind. “What are you doing, Cassy, introducing Alexandra to the maid?”

“I was just about to.” Cassy made the appropriate gestures. “Rosanne, this is Alexandra Waring. Alexandra, Rosanne DiSantos.”

Michael laughed, lumbering down to the group. “Who is this?” he cried, reaching around Cassy to pull Rosanne out into view. “Wooo-weee, look at you! How did you get so gorgeous?”

“Hey, watch the merchandise,” Rosanne warned him.

Alexandra turned to Cassy, smiling slightly. “Has she worked for you long?”

Cassy glanced at her. “Three years.” Her eyes swung back to Michael. “Not to be nosy, but where have you been?”

“Out,” Michael said, yanking the skirt of Rosanne’s dress.

“Yeah,” Rosanne said, yanking her dress back. “Five hours gettin’ ice. Gettin’ iced is more like it.”

“Big bad Rosanne, huh?” Michael said, putting up his dukes.

“You two—” Cassy began.

“Hey, Mr. C,” Rosanne said, sparring as best she could in the confined space, “listen, we gotta go easy on Mr. Moscow tonight. He’s the last guy they’ll send over.”

“Mr. Moscow?” Alexandra asked.

“The bartender,” Cassy said, catching the sleeve of Michael’s sweat shirt. “You better get changed.”

He stopped sparring and looked at her. “I stopped by the station,” he said.

“May I throw my things in there?” Alexandra asked, nodding toward the bedroom. “Cassy?”

“What?”

“My things—may I put them in there?”

“Stop lookin’ at me like that,” Rosanne said, swatting Michael’s arm. “I’m not gonna be a cleanin’ houses forever, ya know.”

“Rosanne,” Cassy said, “will you please get out there and pass hors d’oeuvres? And be forewarned that Amos has an animal on his head.”

“Amos,” Michael sighed, leaning heavily into the wall. “What an asshole.”

“He claims you gave him that thing for his birthday.”

“Yeah,” Michael sighed. “It’s a hyena. Looks like him, doesn’t it?”

“I’m takin’ the sponge with me then,” Rosanne said, moving down the hall, “just so ya know.”

“Cassy—” Alexandra tried again.

“Yes?”

“My things?”

“Yes. In there. On the bed.”

“And I’ll help you,” Michael said, brightening.

Cassy snatched his arm and turned him around. “You, in the kitchen—now.”

“Wait,” Michael said, turning around. Cassy pushed him backward down the hall by his stomach. “No, wait, Cass, I just want to know what Alexandra wants to drink—ALEXANDRA. WHAT DO YOU WANT TO DRINK?”

“Good Lord,” Cassy sighed.

“Perrier!” came the reply.

This did not make him happy. Cranky, “WHAT?”

“Michael,” Cassy said.

“I’d like a Perrier,” Alexandra said, emerging from the bedroom.

“Oh, man,” Michael whined, turning around and walking to the kitchen of his own volition. “What is it with you guys? Get within ten feet of Cassy and suddenly everybody’s drinking Perrier. Shit.”

Cassy waited to escort Alexandra out of the hall. “What do you usually drink?” she asked, letting Alexandra pass in front of her.

“Perrier,” Alexandra said.

A nice figure, too. This is not good. “Really?”

Alexandra turned and smiled. Ratings were made on smiles like these. “Really,” she said.

Cassy’s father, Henry Littlefield, had always told her that she was the most beautiful girl in the world. Cassy’s mother, Catherine, yelled every time he said it. “If you keep telling her that, you’re going to make her a very unhappy woman!”

Cassy was twelve when her father died. Afterward, Catherine—over and over again, year in, year out—strongly advised Cassy to forget everything her father had ever told her. Her explanation ran something like this:

Catherine had been quite a beauty herself, although you couldn’t tell that now. Years of slaving on Cassy’s behalf had destroyed her looks. But the point was, you see, Catherine had been a beauty. Everyone had always told her so and Catherine had believed them. She had also believed everyone when they said that her beauty would win her the best man alive and she would marry him and live happily ever after.

But instead of going for the Miss Iowa title in 1939 (which she won hands down, don’t you know), she should have gone to college and learned something. But she didn’t and she didn’t win the Miss America title, but she did win Henry Littlefield and life went steadily downhill after that.

It wasn’t that Henry had exactly been a bad man. No, no, far from it. It was just that he was so unlucky. Catherine had never seen anyone so unlucky. His career never got off the ground and they never did manage to move out of their starter house (or pay for it) and then Cassy came along and Catherine had to stay home all the time to take care of her and then Henry went off and died on her and Catherine had to work as a receptionist at Thompson Electronics to support Cassy and—

Sigh.

“You know, sweetie, life is tough and then you’re dead and if only they hadn’t all kept telling me how beautiful I was.”

But you’ll be different, honey lamb. I won’t let that happen to you. You’re going to make something of yourself and not end up like your poor old mother.

And Cassy was different, and she did listen to her mother. She was a good girl; she did graduate at the top of her class; she did receive a full scholarship to Northwestern. She didn’t keep bad company (she didn’t really keep any company at all, frankly) and she didn’t fill her head with silly notions about boys.

That is, until Michael Cochran. Oh, but he was handsome in those days. So darkly, devastatingly handsome. (He still was, with a suntan.) And Cassy fell in love with him, despite the fact that she did not want to fall in love with him. He was too wild, too untrustworthy. (She was never quite sure, but over the years Cassy had come to suspect that her falling in love with him may have had something to do with the fact that he had never openly appeared to be in love with her—unlike almost every other man.) But Michael was always laughing, always on top of the world, and was such a good-natured, warm, fun-loving bear of a man—much like Cassy’s father had been. And Michael was so worldly! After six years of working at his home-town paper in Indiana, twenty-four-year-old Michael Cochran was an awesome entity in the journalism school. (Cassy was the second.)

They dated throughout college and Cassy agreed to marry him shortly after graduation. Catherine was horrified and refused to have anything to do with the wedding. If Cassy wanted to marry that “good-time Charlie” and throw her life away, she could go ahead and consider herself an orphan. Cassy and Michael went ahead and got married.

The Cochrans were hired as a team in the news department at a network affiliate in Chicago, Michael as a writer and Cassy as some glorified term for a secretary. They both worked very hard and Michael also played very hard. The guys in management, big drinkers themselves, loved having Michael along on their city jaunts. Michael was a kick; Michael was smart; Michael Cochran was going places.

And so was Cassy—on his coattails. When Michael was offered a producer slot in documentary, he demanded and got Cassy as his assistant producer. They worked extremely well together, Michael with his grand visions and good writing, and Cassy with her sharp technical eye and awesome organizational skills. In short, Michael would get a great idea and Cassy would see that it was carried through to completion. Michael hated details and follow-through (“DETAILS!” he would roar. “FUCK ’EM—LET’S JUST DO IT!”).

Cassy got pregnant in 1968 and miscarried in her third month. But then in 1969 she conceived again and everyone (even her mother, who had deigned to speak to her again) was thrilled when Cassy’s term progressed without any problems. She continued working up to the week Henry was born, and did not return to work full time until two years later, when the biggest documentary of Michael’s life was falling apart—all because of those insidious DETAILS. She had not stopped working since.

They made the move to New York City in 1973 when Michael was offered the job of news director at WWKK. Cassy was hired as a feature segment producer in the news department at rival independent station WST. Both did very well, Michael earning more and more money, and Cassy, in 1976, becoming managing director of news operations at WST. But then, in 1978, Cassy started doing better-well than Michael. She was made managing director of news operations and coprogramming director for the station. But since Michael was a vice-president and she wasn’t, it was okay for a while. But then in 1980 she was made vice-president and managing director, news and programming, and the situation became sticky. And then in 1982, when Cassy was promoted to vice-president and general station manager, the Cochran marriage began to rock. As some sort of unspoken compromise—in terms of work—they spoke of news and only of news, and Michael was to remain the indisputable authority.

So here were the Cochrans of 1986, ensconced in the large West Side apartment on Riverside Drive they had owned for seven years now, both with careers they adored (most of the time) and a son they always adored. They were so lucky in that department, with Henry.

So why did Michael and she have so many problems? Cassy wondered. Problems that were never out in the open, problems that were tied into everything else in such nebulous ways that it was near impossible to even isolate them as such.

Fact (or Fact?): Michael may or may not have had anywhere between fourteen and thirty-seven affairs in the last ten years. (Cassy was always sure, but never really sure, and never wanted to know for sure.)

Fact: Their relationship as husband and wife had evolved into something suspiciously similar to that between an errant student and teacher.

Fact: Cassy and Michael rarely agreed on anything anymore, except a desire not to openly fight. Even on the subject of their son, their viewpoints were so far apart that it was amazing to think they had even known each other for twenty years, much less been married to each other. Michael cast his son as a jock and booming ladies’ man; Cassy knew him as a quiet, shy, gentle young man who was perhaps a bit too smart and too sensitive for his own good. As for the ladies’ man part of Michael’s perception, that only came up when Michael was drinking—when he would attribute all of his own sexual exploits and conquests to his son, going on and on in front of other people, daring to see how far he could go before Cassy showed visible signs of distress.

Looking in the powder-room mirror, tracing the hairs slipping from the clip with her fingers, Cassy considered the amount of gray she could distinguish from the ash blond. She was an expert at this by now. Would she…? No, not yet.

She leaned over the sink and sighed, slowly. She raised her head and again looked at her face. She touched her cheek, her chin, her mouth. Yes, she was still quite beautiful, but she looked like someone else now. Maybe she was a Catherine now, like her mother, too old to be a Cassy.

Good Lord, she was fading. That was it. Just fading. From radiance to glow. Like her eyesight, her face was fading. Reading glasses she had almost resigned herself to, but when it’s your face—what do you do, wear a mask?

Yes. But you call it makeup.

Was it worth it, this life? In love with Henry in the odd moment he expressed a need for her, in love with her television station, in love with her schedules, DETAILS, in love with ignoring the passing days of her life. When, exactly, was it that she had stopped insisting they drive out every weekend to the house in Connecticut? When was it she had decided to let the garden go, and not care if the house was painted or not? When had she stopped wishing they had a dog?

When had Cassy Cochran stopped wishing for anything?

Someone was knocking on the door. “Just a minute,” she called out. And what was this singsong in her voice? Why didn’t she just gently cast flowers from a basket as she walked?

It was Rosanne, balancing a tray of hors d’oeuvres on her hip. “Henry’s on the phone. The kid sounds funny so I thought I better get you.”

Cassy’s heart skipped a beat, for Henry never sounded “funny.”

“I’ll take it in the study.” Cassy walked down the hall and opened the door to the study. It was off limits at parties because it was here that the Cochrans harbored what they did best—sift and sort through work and projects. There were three television sets, two VCRs, tons of scripts, computer printouts and magazines. There were two solid walls of video tapes; the other two walls were covered with photographs of the Cochrans with various television greats over the years and, too, there were a number of awards: Emmys, Peabodys, a Christopher, a Silver Gavel, two Duponts, and even a Clio from a free-lance job of Michael’s years ago. What a lovely mess. Pictures and papers. What they both understood completely. His chair, his desk; her chair, her desk; the old sofa they couldn’t part with, where Henry had been conceived so many years before.

“Henry?”

“Hi, Mom.”

He does sound funny.

“What’s wrong?”

Pause. “Well, Mom, I’m sort of in a situation where I’m not really sure what to do.” Pause. “Mom?”

“Yes?”

He sighed and sounded old. “I’m over at Skipper’s and the Marshalls aren’t home yet.” Pause.

Let him explain.

“Skipper was drinking beer at Shea and then here…Mom, he’s kind of getting sick all over the place and I don’t know what to do.” He hurried on. “I tried to get him to go to bed but he threw up all over the place and then started running around.” Little voice. “He just got sick in the dining room. Mom—”

“Listen, sweetheart, don’t panic, I’m coming right over. But listen to me carefully. Stay with Skipper and make sure he doesn’t hurt himself.”

“He’s sort of out of it.”

“If he starts to get sick again, make sure he’s sitting up. Don’t let him choke. Okay, sweetheart? Just hang on, I’ll be right there.”

Cassy grabbed her coat and purse and went back into the party to find Michael. Easier said than done. Where had all these people come from anyway? Some woman was playing “Hey, Look Me Over” on the piano, while Elvis was belting “Blue Suede Shoes” on the stereo.

Where the hell is Michael?

Where the hell is Alexandra Waring?

Well, at least Cassy knew who was with whom.

The Marshalls lived on Park Avenue at 84th Street. Skipper was a classmate of Henry’s, a friendship sanctioned by Michael since Roderick Marshall was the longtime president of the Mainwright Club, of which Michael yearned to be a member. (He was turned down year after year.) As for Cassy, she thought the Marshalls were stupid people. Period. And because she felt that way, she had become rather fond of Skipper for openly airing all of the family secrets (his mother had had two face lifts; his father went away on weekends with his mistress; they had paid two hundred and fifty thousand dollars to marry off Skipper’s hopeless sister…).

While Cassy wouldn’t have chosen Skipper as Henry’s buddy, she did appreciate one of Skipper’s attributes—he absolutely worshiped the ground Henry walked on. And he was bright; he understood all of Henry’s complicated interests; and he was loyal, not only to Henry, but to all of the Cochrans. (Whenever Cassy told the boys it was time to go to bed, Skipper always made a point of thanking her for letting him stay over. “I really like it here,” he would declare. “I would really like it if you liked my liking it—do you, Mrs. C?”

“Yes, Skipper, I do,” Cassy would say, making him grin.)

The poor kids. Cassy found Henry sitting shell-shocked on the lid of the toilet seat in the front powder room while Skipper snored on the tile floor, his arm curled around the base of the john. Lord, what a mess. Henry held Skipper up so that Cassy could at least wash the vomit off his face and take off his shirt. They took him to his room, changed him into pajamas, and then put him to bed in one of the guest rooms since his own was such a mess. With Henry’s help she found the number of the maid and Cassy called. Would she come over since no one knew where the Marshalls were, or when they could come home? She would.

Cassy stripped the sheets in Skipper’s room and, with Henry, cleaned up the worst from the carpets around the house. Aside from answering her questions about where things were, Henry hadn’t volunteered anything. Cassy checked on Skipper again; he was long gone, in a peaceful sleep now.

They sat in the kitchen and shared a Coke.

“Are you sure the Marshalls didn’t leave a number?”

Glum. “Yes.”

“Henry,” Cassy asked after a moment, “do you like to drink?”

He glared at her. “Mom.”

“No, sweetheart, it’s okay. I mean, I know all kids experiment sometime. I just wondered about you. About how you felt about alcohol.”

He shook his head and looked down at the table, restlessly moving his glass.

“Henry—”

“I hate it.” His voice was so low, so hostile, Cassy wasn’t sure she’d heard it right.

“What, sweetheart?”

He looked up briefly, let go of his glass, and leaned back on the legs of the chair. He caught his mother’s look and came back down on the floor with a thump. Back to the old tried and true position. “I hate the stuff. It makes me sick.” A short pause. “Why do people have to drink that stuff? It just makes them act like jerks and it’s not good for your body, so what’s the point?”

Cassy’s mind raced with that one. After a moment she asked, “Does Skipper drink a lot?”

Henry gave her a does-he-look-like-he-does-silly-old-Mom look. “He tries to.”

“Has he ever said why?”

Another look, not dissimilar to the last. “No. He just does it whenever he’s pissed at his parents.”

“Angry.”

“What?”

“Angry at his parents.”

“Yeah, anyway—today his mother told him he couldn’t go to Colorado.”

“Why not?”

Henry shrugged. “Bad mood, probably. She’s like that.”

By the time the maid arrived, Cassy had changed her mind about what to do. She apologized to Angie for bringing her over, and explained that she had second thoughts about sticking her with the situation. Cassy would take Skipper home with her. She left a note by the front door:

Deidre,

Skipper is safe and sound at our house. He is not feeling very well and since I didn’t know where to reach you, I thought it best to bring him home with me. Call me when you get home and I’ll explain.

Cassy Cochran

Michael was bellowing “My Wild Irish Rose” down the hall for the benefit of departing guests. Cassy sighed, Henry’s back snapped to attention and Skipper, bless his heart, did his best to move along between them without letting his eyes roll back into his head.

“Hey, kid, nice to see you! Didn’t want to miss the fun with your old man, huh?” Michael said, holding his glass high. “Hey, Skip!”

“Skipper’s ill,” Cassy said, ushering Skipper by him. “I’m putting him to bed in the guest room.”

“Too bad, Skipperino,” Michael said. He got hold of Henry’s arm. “Come on,” he urged, pulling him along. “Kiddo, I want you to meet one hot cookie. Our new star.” He halted suddenly, pretending to whisper. “Kid, she’s so beautiful—I can’t tell you how beautiful she is, so hold onto your hat…”

Cassy was reluctant to leave Henry, but Skipper was fading fast. Rosanne, in the kitchen, took one look at him and followed them back to the guest room. While Cassy stripped Skipper down to the pajamas he was wearing under his clothes, Rosanne turned down the bed and set out a pail beside it. Cassy sat for a minute or two with Skipper, reassuring him that he would be feeling better after he slept, stroking his forehead all the while. She left the hall light on and the door open.

When Cassy went into the living room, she found Michael practically shoving Henry into Alexandra’s lap on the couch. When Henry saw his mother it apparently gave him courage, for he slapped his father’s hand away, excused himself to Alexandra, shot past Cassy without a word and headed for his room.

There were only six guests left—the die-hards, five of whom were in worse shape than Michael. Alexandra was stone cold sober and looked as though she wished she could go to her room too.

Hmmm.

Cassy went into the kitchen, where Ivor asked her what she would like to drink. She asked for a Perrier, changed her mind, and asked for a glass of white wine.

“That Waring chick is a strange one,” Rosanne said, rinsing a tray in the sink. Clang, clatter, into the rack.

Cassy accepted her glass of wine, sipped it, and moved across the kitchen to lean back against the counter. “Why, what did she do?”

Rosanne pulled off her rubber gloves, untied her apron and threw it on the dish rack. “She comes in here like the Queen of Sheba and so I look at her, and like Mr. C’s standin’ over there by the bar.”

“And?”

“And so she stands there,” Rosanne continued, pointing at the very spot on the floor, “and says”—Rosanne stood on her tiptoes to accurately re-enact the scene— “‘Where is Mrs. Cochran?’ So I said”—dropping down to her heels, plunking a hand on her hip— “‘If she’s got any sense, she’s hidin’ from the likes of you.’”

“Oh, Rosanne,” Cassy groaned, covering her face.

“Naw, naw,” Rosanne said, shaking her head. “I didn’t say that. I said, ‘She’s out.’ So she says—” back on her toes— “‘When is she coming back?’ So then Mr. C says”—holding her arms out to the side, implying largesse— “‘What do ya want Cassy for?’ And she says, ‘I’d like to know her better,’ and so then Mr. C starts gettin’ upset, and she says—cheez it, the cops.”

Cassy was about to say, “Alexandra Waring said, ‘Cheez it, the cops’?” when she realized that Michael and Alexandra had come into the kitchen. A look back at Rosanne found her busy at the sink, minding her own business of course.

“So what’s with Henry?” Michael said, shoving his glass into Ivor’s hand and then grunting.

“He’s had a rough afternoon.” Cassy glanced at Alexandra and added, “We’ll talk about it later.”

“Brooding kid sometimes,” Michael said to Alexandra. “Oh, thanks, Igor.”

“Ivor, Michael—the man’s name is Ivor,” Cassy sighed, sitting down on a stool.

“Igor, Ivor, you don’t care as long as you get paid, right?” he said, slapping Igor-Ivor on the arm.

Cassy noticed that Amos’ hat was leering down from on top of the refrigerator, a cigarette dangling from its jaws.

Michael turned to Alexandra. “You know where the kid gets it from?” He swallowed almost his entire drink and laughed. “We made the kid on the couch I showed you in the den—” He started cracking up.

“Michael—” Cassy said.

“And the whole time, Cass kept oooing and ahhhing and then all of a sudden she starts yelping about a spring stabbing her in the rear end—”

Cassy slumped over the counter.

“And the kid inherited it! He gets this look like—Jesus, something’s stabbing me in the rear end.” Michael fell back against the doorway, hysterical. “You saw him, Alexandra! Isn’t that what he looks like?”

Rosanne hurled a handful of clean silverware into the sink; Ivor examined the wallpaper; Michael continued laughing and Cassy left the room. She was halfway down the hall when she heard her name being called. It was Alexandra. Cassy turned around and stood there, waiting.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“Why,” Cassy said, “what have you done?”

“No, that’s not what I meant, I—”

Cassy silenced her by raising her hand. “Look,” she said, “do me a favor, will you? Just please get out of here and take those drunken idiots with you. Michael included. All right?” And then she fled to the guest room, slamming the door behind her. Having awakened poor Skipper, Cassy stayed with him for a while until he fell back to sleep. When she emerged from the room, she found that Alexandra had granted her her favor; the party had departed for dinner at Caramba’s.

They didn’t say much while cleaning up and were done by ten-thirty. When Cassy paid Ivor and tipped him well (in the far-flung hope he might give the agency a favorable report), Rosanne whispered to offer him Amos’ hat. Cassy stared at her. She nodded. And so she did, and Ivor took Amos’ hat home with him in a Zabar’s bag.

“I had a hunch he liked it,” Rosanne said after he left. “He kept lookin’ at it.”

Cassy asked Rosanne if she wanted some hot chocolate; she was making some for Henry and herself. Rosanne declined, saying she had to get going—had to be at Howie and the Bitch’s early the next morning.

“Do you know how I cringe, Rosanne, when I think of how you must describe us to your other clients?” Cassy said, stirring Ovaltine into a saucepan of milk.

“I call ya the C’s, that’s all,” Rosanne said. “Honest.”

Cassy smiled slightly.

“Well,” Rosanne reconsidered, slipping on her coat, “maybe once I said that Mr. C stood for Mr. Crazy.”

Cassy wanted to say something but didn’t. She just stirred and stirred until the handle of the stainless steel spoon was too hot to hold. She put it down on the stove top. What was this? Tears? Yes, a tear, spilling down her cheek. And she wasn’t even crying. At least she didn’t feel as though she was crying. She wiped at her face with the back of her hand, sniffed, and said, “I’m sorry, I’m just so tired…”

“Mrs. C,” Rosanne said, moving to the doorway. Cassy didn’t look up. “Like it’s never easy, ya know?”

“No,” Cassy finally said, “I don’t suppose it is.”

Silence.

“Thanks a lot for the dress. I really like it.”

Quietly, “You’re welcome.”

And Rosanne left.

Henry accepted his hot chocolate and put an issue of the Backpacker aside.

“I think Skipper will be fine,” Cassy reported, sipping from her mug. “When do you suppose the Marshalls will get home?”

“They won’t call, Mom, so don’t wait up for them.”

After a moment Cassy patted Henry’s knee and he scooted over so she could sit next to him on the twin bed. It was a tight fit, but a well-practiced maneuver. They drank their hot chocolate, both looking across the room at the window.

“Tug?” Cassy asked.

“Police boat,” he said. Henry knew all the boats on the river at night.

“Oh, yes.”

Silence.

“Mom,” Henry said, “do you ever get scared for no particular reason?”

She swallowed. “Sometimes. Usually when I’m wondering what’s going to happen. Life always seems like an unlikely proposition when I try to figure out how everything’s going to turn out.”

Pause.

“What are you going to do, Mom?”

“Talk to Mrs. Marshall.”

Long pause. “I meant about Dad. He’s really getting—you know, like that summer in Newport.”

Cassy looked at her son. How much did he know? “What do you mean?”

Henry was uncomfortable. “You know, that woman. He’s acting like that again.”

So he did know. Probably more than Cassy herself knew. If she hadn’t wanted to know for sure about Michael’s affairs, she supposed she was about to find out.

“Mom—why don’t you do something?” This was delivered in a whisper.

Where the energy came from she wasn’t sure. But it came. She put her cup down on the night table and put her arm around Henry. She sighed. “Sweetheart, Henry, your father and I, no matter what our troubles—we both love you more than anything else in the world.”

Silence.

“Mom, he humiliates you. He humiliates me. Is he sleeping with that woman who was here tonight? If he is, why doesn’t he do like other guys and at least hide it?”

Cassy felt nauseous.

“He just throws it in your face. Rosanne knows it, I know it, half the station knows it. Why don’t you do something?”

Cassy vowed not to cry. Quietly, “What do you think I should do?”

“I don’t know. Talk to him.” And then, blurting it out, “Make him love you again.”

“Oh, sweetheart.” Cassy was close to breaking down. What to say, God, what to say? Did her son not think she had tried?

The pain was centered right there, right on that. I have not tried and we both know it.

Cassy raised her head and saw that Henry was not angry with her; he was trying to comfort her. Tell her he was on her side.

When did he start needing to shave? was her next thought. When did that happen?

The doorbell was ringing. Cassy kissed Henry on the cheek, got up and slipped on her shoes. The doorbell was persistent. She leaned over and kissed Henry again. “It’s probably Mrs. Marshall,” she said.

Cassy was hardly in any shape to deal with Deidre Marshall, but, she thought, anything was an improvement over continuing that talk with Henry. She swung open the front door just as she thought she should have peered through the peephole first.

It was Alexandra Waring.

Rubbing her eye, Cassy had to laugh to herself.

Alexandra shifted her stance slightly. “I told them I was tired,” she said.

“You came to the right place, then,” Cassy said. “We always are here.”

The brilliant eyes were asking for mercy and it threw Cassy. What was up?

“May I come in for five minutes? There was something I wanted to say to you.”

“To me?”

Alexandra nodded.

“Well,” Cassy said, stepping back and waving her in, “I suppose you’d better come in and say it then. Let’s go in the living room.”

It fascinated Cassy how nervous the girl was. Offered a chair, she declined, choosing instead to pace the floor with her hands jammed into the pockets of her raincoat. Cassy sat down on the couch and watched her. Alexandra looked over at her once or twice but continued to pace.

This was to be the woman to launch a thousand broadcasts? Tell of earthquakes? Assassinations? Terrorism? Fatal diseases? This was Michael’s Wonder Woman? Well, Cassy would be kind. She would assume that Alexandra could do better sitting behind a desk.

The girl finally said, “I want to apologize and I’m not exactly sure what I’m apologizing for, since I haven’t done anything wrong.”

Cassy lofted her eyebrows.

The girl started to pace again, stopped, and suddenly threw herself down on the end of the couch, to which Cassy reacted by crossing her legs in the opposite direction.

“There’s no other way to say it, so I’ll just say it. I’m terrified of your husband, of offending him, because I desperately want this assignment to work.” She ran her hand through her hair and dropped it in her lap. “Tonight was a nightmare and I couldn’t stand watching what was happening, but I couldn’t do anything either—can you understand that?”

Somewhere, perhaps between the words “terrified” and “desperately,” a gray veil had dropped over Cassy’s head, shielding her from any sense that this conversation was actually taking place.

Alexandra sighed, lowering her head for a moment. Cassy noted how gorgeous her hair was. No gray. Nothing but black, thick, wonderful young hair. How crazy it must make Michael.

“Are you having an affair with my husband?”

Alexandra’s head kicked up. “God, no,” she whispered. “Never. I wouldn’t do that—”

Cassy shrugged. “Thought I might as well ask.”

“I’m very fond of your husband,” the girl said. “I’m also very loyal to him. You of all people must realize the enormity of the opportunity he’s giving me.”

Cassy nodded. “Yes, I do.”

“So you can understand how difficult my situation is.”

Cassy sighed, looking past her to the window. A barge was making its way down the river.

“Tonight, when I saw you—” Alexandra said, voice hesitant. “I’ve heard about you, your career—people told me how beautiful you are—”

Cassy winced slightly. If you think I’m beautiful now, you should have seen me before.

“So when I saw you tonight,” Alexandra rushed on, “I knew at once that something had to be terribly wrong if he—” She cut herself off. “Oh, God, I’m sorry—this is coming out all wrong—”

Cassy held a hand up for her to stop. “Look, Alexandra, I appreciate what it is you’re trying to do—”

“But I can’t do anything, that’s the point—”

“Please, listen to me for a minute, will you?” The girl leaned back against the arm of the couch. It was a good move, Cassy noted, the way she had posed herself. The way Alexandra looked at this moment was enough to make Cassy want to slash her wrists to put an end to this curse of middle age once and for all. “In my day, if you got anywhere in news—really, anywhere in almost any profession, women were always accused of sleeping their way there.” She laughed slightly. “And I did—I was married to Michael and he was my boss. Did you know that?”

“He’s told me everything about you,” Alexandra said, faint smile emerging. “He talks about you a lot.”

Cassy nodded. “Okay. Well, the only point I want to make is that all women, particularly beautiful women, sooner or later have a Michael making their lives difficult. The fact that it is my husband, I can’t—I won’t—”

“Of course not. I can handle him—it—that,” Alexandra said. “What’s difficult is just what you said—about being accused of sleeping…” She sighed, running her hand through her hair again. She looked at Cassy. “Everyone thinks I’m sleeping with him—and that’s why he brought me to New York.”

Cassy rubbed her face, thinking, Lord, what must I look like? “If I were you,” she said, lowering her hands, “I would just go on doing what you’re doing and let them think whatever they want. Alexandra—they’re going to think whatever they want to think anyway. No matter what you do. I think you know that.”

Alexandra lowered her eyes. “I care what you think,” she said. “That’s why I came back.”

Michael, you’d be crazy not to want to marry this girl. Either she was a first-rate liar, or she was a nice girl from Kansas. “I think—” Cassy began, starting to smile.

Alexandra met her eyes.

“If you’re half the person on air that you are right now, you’re going to be just fine.”

“Thank you.” It was scarcely a whisper. They were still looking at each other and Alexandra suddenly pulled her eyes away.

“Alexandra—”

The girl started.

Either Cassy was seeing things, or the nice girl from Kansas was blushing.

“I was just going to say that a friend of my son’s is here, who’s sick, and I’m rather tired and I think you are too…”

“Yes, of course,” Alexandra said, rising.

In the kitchen they found Henry with his head in the refrigerator. He jerked back, first looking at Alexandra and then to his mother.

“It’s okay, sweetheart,” Cassy said.

“Henry,” Alexandra said, going over and shaking his hand, “I hope I see you again one day soon. When it’s a little less rowdy.” Pause. A gesture to Cassy. “Your mom and I were just talking—well, she’ll tell you.”

Henry looked to his mother and Cassy nodded, smiling.

“I’m just going to see Alexandra to the door.” Cassy led the way through the front hall. “Well, it’s been quite a day,” she said, opening the door.

“Yes,” Alexandra sighed, stepping outside the door and turning around.

Cassy held out her hand and Alexandra shook it. “Thank you, Alexandra. You’re a very courageous young lady.”

Alexandra smiled.

The ratings have just soared in the tri-state area.

“Thank you for being so nice,” Alexandra said. She let go of Cassy’s hand, walked down to the elevator and pressed the button. “Will I see you again soon, do you think?”

“Well,” Cassy said, hanging on the door, “I’ll be seeing a lot of you. We tend to watch a lot of news around here.”

“Great,” Alexandra said.

“Good night,” Cassy said, closing the door.

“Good night.”

Cassy locked the door and leaned against it. And then, after hesitating a moment, she ventured a look out the peephole.

He won’t give up on this one, she thought.