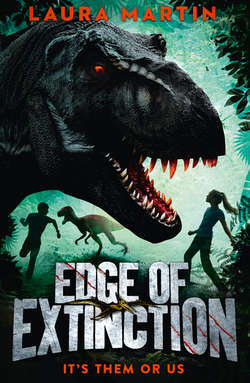

Читать книгу Edge of Extinction - Laura Martin, Laura Martin - Страница 7

Оглавление

I needed to get away from the compound entrance before someone came to investigate my report. As I got to my feet, I eyed my reflection in the glossy surface of the holoscreen. Sweat dripped down my face, my grey eyes looked a bit wild and my curly red hair had broken free from its ponytail. As I battled to get it back under control, I remembered my dad standing behind me, a look of pure bafflement on his face as he tried to force my hair into some sort of order. At times like that, I think both of us had thought about my mum and how, if she hadn’t died giving birth to me, it probably would have been her teaching me about hairstyles. He’d actually got pretty good at it before he’d disappeared, but I’d never developed the knack. Now I scraped it back into its ponytail. It would have to do. I set out at a jog.

The floor of the tunnel slanted downwards as I wound my way through the cement maze that made up North Compound. Of the four compounds in the United States, North was the smallest. Sometimes I loved that, but most of the time I didn’t. It meant that I knew everyone in the compound and everyone knew me. Which would be fine, if everyone also didn’t hate me.

I’d played around with the idea of asking for a voluntary transfer to East Compound or West Compound, but I’d never been able to bring myself to do it. The clues to my dad’s disappearance were here. So here was where I had to stay. I turned a corner and ran past countless doors embedded in the tunnel wall but ignored them. They were empty by now anyway – everyone needed to report to work by seven fifteen sharp if they wanted to avoid a late penalty. That thought had me picking up my pace. Goose bumps broke out on my arms as the temperature dropped the further down into the compound I went, the walls alternating between the smooth concrete of man and the rough rock of nature.

The North Compound, like the other three compounds, had originally been built as a bunker in case of nuclear decimation or something like that. Almost two hundred years ago, engineers had sat around discussing how to turn an abandoned rock quarry into an underground city where people could survive for months or even years. They had no way of knowing that what they built would protect the human race, not from nuclear fallout but from animals that had been extinct for thousands of years. I wondered if they would have designed things differently if they’d known.

Five minutes later I was out of the habitation sector and entering the main labyrinth. Here the tunnels bustled with activity as men and women, wearing the same faded grey as myself, hurried off to their various occupations. I weaved my way through the crowd, avoiding eye contact. Five years had taken the edge off most of the residents’ general dislike for me but hadn’t dulled it completely. I did my best to stay off their radar, and in return they didn’t go out of their way to give me dirty looks. It wasn’t a foolproof system, but it worked.

I made it through the crowd and jogged down the side tunnel towards the school sector and my homeroom. Right before I rounded the last turn, a muffled sob brought me to a halt. Not again. I groaned as I backtracked down the tunnel. Stopping outside the third storage door, I lifted the latch and flicked on the light.

Shamus was sitting in the corner of the small stone room, wedged between two stacks of broken desks, just like I knew he would be. His big blue eyes blinked up at me, and I sighed. Shamus Clark was five and, like me, a social outcast. His father was the allotment manager, the most hated job in the NC. No one liked to be told that their food ration had been cut. Unfortunately, the other kindergarteners in Shamus’s class had inherited their parents’ prejudices. I knew how that felt all too well.

“Toby again?” I asked, wiping a tear off his chubby cheek with my thumb.

Shamus nodded, scrubbing at his snotty nose with his sleeve. “He … he pushed me down, and he took my lunch ticket. I scraped my knee. See!” Tears momentarily forgotten, he proudly showed me a small scrape.

Lunch tickets were given out to each family as part of their weekly allotment and were the first thing taken away if a job was shirked or done poorly. Knowing your child would go hungry was enough to keep people reporting to work every day. It was a harsh system, but it was fair. Although that could be said about every aspect of compound life. I frowned. No matter how good the system was, it hadn’t prevented Shamus from being bullied. Toby’s parents didn’t seem to care that Toby stole Shamus’s lunch tickets because they failed to provide them for him.

“You are going to have to start standing up for yourself,” I explained gently, pulling Shamus to his feet and brushing dirt off his uniform. He wiped his eyes and looked unconvinced. “You know he only takes it because he’s hungry, right?” I sighed. “Let’s go. We need to get you to class.” Shamus trudged along beside me, his hot little hand grasping mine, and I felt a flash of guilt. If I’d got eaten this morning, who would have found Shamus in the broom closet?

I knocked on the door of Schoolroom A, and the kindergarten teacher, Mrs Shapiro, answered looking annoyed. With a wide smile I didn’t really mean, I ushered Shamus into the room.

“I’m sorry he’s late. It’s completely my fault.”

Mrs Shapiro huffed in exasperation, slamming the door in my face. Lovely.

Two minutes later, I slid through my classroom door and to my desk in one seamless motion, keeping my eyes down in the hopes that Professor Lloyd wouldn’t see me if I couldn’t see him. Slipping my port out of my backpack, I laid it on my desk and finally looked up. Luckily, his back was to me as he scrawled out an agenda on the board.

“Not bad,” quipped a familiar voice at my elbow. I flicked my eyes up to see Shawn Reilly grinning at me from across the aisle. I rolled my eyes and bit back a smile.

“Shamus,” I mouthed in explanation as I turned on my port. Its screen flashed blue and then green.

Shawn held up three fingers, wordlessly asking if it was the third time in the last few weeks that I’d had to help out Shamus.

I shook my head and held up four. He nodded. The PA system hissed and crackled, and we all fell silent as we waited for the day’s announcements.

“Good morning,” barked the voice of our head marine, First General Ron Kennedy. I wrinkled my nose in dislike. Each compound had ten marines stationed to keep the peace and assist in brief forays topside for things like tunnel reinforcements. They were the Noah’s eyes and ears at each of the compounds, reporting back problems that arose. Of those ten, General Kennedy was my least favourite. “Today is Monday, September 1. Day number 54,351 here in North Compound.” Kennedy went on. “Please rise for the pledge.” As one, the class rose and turned to face the black flag with the Noah’s symbol of a golden boat positioned in the corner of the classroom.

“We pledge obedience to the cause,” the class chanted in unison, “of the survival of the human race. And we give thanks for our Noah, who saved us from extinction. One people, underground, indivisible, with equality and life for all.” We took our seats.

“Tunnel repairs are continuing,” General Kennedy’s voice went on, “so please avoid using the southern tunnels in sections twenty-nine to thirty-four unless absolutely necessary. Mail was delivered today,” he said, and then he paused as though he could hear the excited murmur that had greeted this news. Mail was delivered only four times a year between compounds, and sometimes less than that due to the danger of sharing the skies with the flying dinosaurs. Although I was pretty sure the ones that flew and swam weren’t technically considered dinosaurs. I remembered a science lesson where we’d learned they were really just flying and swimming reptiles, but I didn’t see what the difference was.

“As always, the mail will be searched and sorted before being delivered. We appreciate your patience as we work to ensure the safety of all citizens here in North.”

When I glanced up, Shawn was studying me suspiciously, his brow furrowed over dark blue eyes.

I tried to keep my face blank, like the mail being delivered and my being late had absolutely nothing to do with each other. But I was a horrible liar.

“It wasn’t just Shamus, was it?” Shawn hissed, pointing an accusing finger at me. “You were checking the maildrop again.”

“Shhhh,” I hissed back, as General Kennedy went on to discuss the upcoming compound-wide assembly scheduled for later this week.

“You are going to get killed,” Shawn frowned. “And all for some stupid hunch.”

“I won’t.” I huffed into my still-wet fringe in exasperation, wishing that I’d chosen a best friend who wasn’t so nosey. “And it isn’t a hunch.”

Shawn raised an eyebrow at me. “OK,” I conceded. “It’s a hunch.” But just because year after year there’d been no mention of the disappearance of the compound’s lead scientist didn’t mean there never would be, I thought stubbornly. How could I explain to Shawn the pull I felt to find out what had happened to my dad? I imagined it was similar to what it felt like to lose a limb, a constant nagging sense of something missing, a dull ache that wouldn’t go away.

“It’s been almost five years,” Shawn pointed out. “The odds that you are going to find out anything at this point are low.”

“Does that mean you don’t want to see the information I got?” I asked, trying hard to keep a straight face.

“I didn’t say that,” he grumbled, and I grinned, knowing I’d won.

“You should have at least told me you were going topside so I knew to send the marines’ body crew out for you if you didn’t make it back,” Shawn grouched. I made a face at him. The marines’ body crew was a standing joke between us. There was no such thing as a body crew in North Compound, because what lived above us didn’t leave bodies behind. The crackling of the PA system signalled that announcements were over and I turned my attention back to the front of the classroom.

“Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd called out, and I jumped. “I can only assume you were late because you were spending your time studying for our literary analysis today. Please stand,” he said, not bothering to look up from his port.

“Busted,” Shawn hissed.

“You too, Mr Reilly,” Professor Lloyd said. Someone sniggered, and my face turned bright red as I stood. Shawn grumbled something incoherent, but he stood as well.

“All right, Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd said, glancing down at the port screen in front of him. “If you wouldn’t mind giving the class an explanation of the similarities between the events that transpired in Michael Crichton’s ancient classic Jurassic Park and the events that have transpired in our own history.”

“Similarities?” I asked, swallowing hard. I’d just finished reading the novel the night before, so I knew the answer, but I hated speaking in public. Facing the pack of deinonychus again would have been preferable. I wasn’t sure what that said about me.

“Yes,” Professor Lloyd said, a hint of annoyance creeping into his voice. “Quickly, please. We are wasting time that I’m sure your classmates would appreciate having to work on their analyses.”

“Well,” I said, keeping my eyes on my desk, “in Mr Crichton’s book, the dinosaurs were also brought out of extinction.” I glanced up to see Professor Lloyd staring at me pointedly. He wasn’t going to let me get away with just that. Clenching sweaty hands, I ploughed ahead. “The scientists in the book used dinosaur DNA, just like our scientists did a hundred and fifty years ago. And just like in the book, our ancestors initially thought dinosaurs were amazing. So once they had mastered the technology involved, they started bringing back as many species as they could get their hands on.”

“Thank you, Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd said. He turned to Shawn, who had propped one hip on his desk while he was listening to me, the picture of unconcerned boredom. Professor Lloyd noticed too and frowned. “Mr Reilly, if you wouldn’t mind explaining the differences between Crichton’s fiction and our own reality?”

“Sure,” Shawn said, with a wide grin. “Well, the obvious one is the size of the dinosaurs, right? I mean, ours are gigantic. Almost twice the size of the ones that Crichton guy talks about.”

“That’s correct,” Professor Lloyd said, addressing the room. “As Mr Reilly so eloquently put it, that Crichton guy based his dinosaurs on the bones displayed in museums and pictured in Old World biology books. What Crichton didn’t take into account was how different our world was compared with the dinosaurs’ original harsh habitat. Chemically enhanced crops, gentler climate and steroid-riddled livestock made them grow much larger than their ancient counterparts.”

“You can say that again,” Shawn said, and the class chuckled. I didn’t laugh. The memory of my close call with the pack of deinonychus was still too fresh. They’d seemed massive, and they weren’t even one of the bigger dinosaurs. The compound entrances were set in a small clearing bordered by fairly thick forest, which made it impossible for the larger dinosaurs to get too close.

“Anything else, Mr Reilly?” Professor Lloyd asked, a hint of annoyance back in his voice.

“Yeah,” Shawn said. “The people in the book didn’t have them as pets, on farms, in zoos, or in wildlife preserves like we did before the pandemic hit. They were mostly kept to that island amusement park thing.”

“And why is that important?” Professor Lloyd prompted.

Shawn rolled his eyes. “Because when the Dinosauria Pandemic hit our world and wiped out 99.9 per cent of the human population, it was really easy for the dinosaurs to take over. Which is why we now live in underground compounds, and they live up there.” He pointed at the ceiling.

“For now,” Professor Lloyd corrected. “Our esteemed Noah assures us that we will be migrating aboveground as soon as the dinosaur issue has been resolved.”

“They’ve been saying that for the last hundred and fifty years,” I muttered under my breath, just loud enough for Shawn to hear. He flashed a quick grin at me. The different plans to move humanity back aboveground had spanned from the overly complicated to the downright ridiculous, but each time a new plan was brought up, the danger of the dinosaurs was always too great to risk it.

“So in summary,” Professor Lloyd said, motioning for us to have a seat, “the scientists of a hundred and fifty years ago were unaware that by bringing back the dinosaurs, they were also bringing back the bacteria and viruses that died with them. And as you all know about the disastrous devastation of the Dinosauria Pandemic, I will stop talking to give you as much time as possible to complete your literary analysis. You may access the original text on your port screens.”

I glanced down at my port screen, where the text had just appeared. Professor Lloyd was right – we all did know about the disastrous effects of the Dinosauria Pandemic; we lived with them every day. I tried to imagine what it had been like back then. The excitement as scientists brought back new dinosaur species daily. The age of the dinosaur had seemed like such a brilliant advance for mankind. How shocked everyone must have been when it all fell apart so horribly and so quickly.

The Dinosauria Pandemic had hit hard, killing its victims in hours instead of days like other pandemics. It had spread at lightning speed, not discriminating against any race, age or gender. I could just imagine how shell-shocked the few survivors must have been, those who’d been blessed with immunity to a disease that should have been extinct for millions of years. They must have thought the world was ending. And I guess, to some degree, it was.

One by one, the countries of the world had gone dark as news stations went off air and communication broke down in the panic that followed. I wondered if anywhere else had fared better than the United States. Were there underground compounds sprinkled throughout Europe? Asia? Africa? Were people thousands of miles away huddled together thinking they were the last of the human race just like us? I hoped so, but I doubted it.

The United States had got lucky to avoid extinction. With no formal government left standing, one man had stepped up to rally what was left of humanity. He’d called himself the Noah after some biblical story about a man saving the human race in a big boat called an ark. He’d arranged for the survivors to flee into the four underground nuclear bomb shelters located in each corner of the United States. And once we were out of the way, the dinosaurs quickly reclaimed the world, and we’d never been able to get it back.

I pulled up my copy of Jurassic Park on my port and flipped through the pages, looking for something I could use in my analysis. I’d hated reading Crichton’s book, and I doubly hated having to write about it. His descriptions of life topside made my insides burn with jealousy. It wasn’t fair that one generation’s colossal mistake could ruin things for every generation to come.