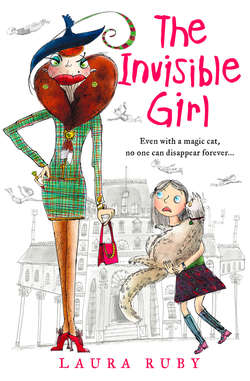

Читать книгу The Invisible Girl - Laura Ruby, Laura Ruby - Страница 9

Chapter 4 Bugged

ОглавлениеTHE BOY BOUNCED DOWN THE corridor, punching the wall every few feet or so. Feline Face. Bug Eye. Lizard Man. Any of those names would have been all right with him; he knew his eyes were so big and far apart they were practically on the sides of his head. So, fine. Bug. Bugs were cool. Bugs could fly. Some, like praying mantises, even had those sweet backward scythes for arms. He wondered why grown-ups had operations to have their eyebrows pasted up on their foreheads or fat vacuumed from their butts but never got anything practical. Like antennae. Or fangs. Or scythes for arms. The boy would have enjoyed having scythes for arms because then he could slash through the fence around Hope House for the Homeless and Hopeless and fly away for ever. Instead, he was stuck here with Mrs Terwiliger. Mrs Terwiliger looked like a flying Pez sweet dispenser.

He stopped and jumped as high as he could, but his feet were so heavy. It was like he had been chained to the ground. Wham! He punched the wall so hard he bloodied his knuckles and had to stuff his fist in his mouth.

She named him Chicken. Chicken! Chickens couldn’t fly. Why chickens were even considered birds was a mystery. They were more like walking cushions or fat clucking possums or something.

He tried to jump again, his feet sticking to the floor. Wham! Wham! Wham! He didn’t cry out at the pain in his hands; he welcomed it. It kept his mind off everything else. This stupid place. His stupid new name. The stupid food, worse than monkey chow. The fact that he could hardly get his feet off the ground when in his mind and in his dreams, he could soar.

If only he knew who he was. Who he really was. The other kids said that no one ever remembered much about who they were when they came to Hope House, not even their own names, that your memories faded as soon as you crossed the threshold. Bug did remember crossing the threshold, sitting in Mrs Terwiliger’s office and being snarky when she asked for his name: “Mary Poppins! Harry Potter! Stanley Yelnats!” He also remembered hearing music—maracas or cymbals or something—and whispering in someone’s ear. But whispering in whose ear? And whispering what? His real name? His address? His favourite colour? He just didn’t know. But it was better that way, the other kids told him. Otherwise, you’d spend all day crying over the fact that your parents died or your Aunt Lucy gave you away like a pet parrot who talks too much and poops all over the floor. And who’d want to know that? Better to forget. Better to jump up and down like an idiot in the playground at Hope House, wishing that one day you’d make it more than a couple of feet.

“Meeow.”

Bug—if he had to have a name, that was the one he wanted, thank you very much—swung around, bloody fists high. Something small and fuzzy was sitting at the end of the hallway, near the entrance to the girls’ dormitory. What the heck was that, he thought. A rat? City rats could grow big, he knew. The subways were overrun with them. Hairy, dog-sized things with long yellow teeth, all the better to gnaw you with, my dear.

He walked cautiously towards the animal, whatever it was, ready to kick. (He wasn’t about to get gnawed on by an overgrown rodent. Nuh-uh.)

But it wasn’t a rat. It was a cat. He’d never seen one before. Not a real one.

Bug lowered his fists and stared at the cat. The cat stared back. Then it dropped to the floor and rolled around in what Bug thought was a sort of happy way. A friendly way. A hello, how-are-you-I’m-fine kind of way. It looked like fun, or at least distracting. Since no one was around, since flying was futile and since he’d probably break his knuckles if he kept punching the walls, Bug dropped to the floor too and rolled from one side to the other. Encouraged, the cat rolled back the other way, and soon they were both rolling at the same time and in the same direction, back and forth, back and forth. Bug could have sworn the cat was smiling.

A girl ran out of the dormitory and into the hallway, almost tripping over Bug and the happily rolling cat. The cat got to its feet and wound itself around the girl’s ankles. After scooping up the cat, she glared down at Bug as if he were…a bug.

He was embarrassed to have been caught rolling around on the floor, but not too embarrassed to notice how tightly the girl was holding on to the cat. As if she thought it belonged to her. “What’s your problem?” Bug asked her.

The girl bit her lip. She was that weird girl, the one just called Gurl. The one who watched everyone. The other kids said that since she didn’t look like any particular thing and couldn’t seem to do any particular thing, Mrs Terwiliger chose the obvious name. Bug himself might have tried to be a little bit more creative. Pasty Face would work, he thought. Or Ghost. Spooky! Now that was a good name for her. Her skin was white and her long dishevelled hair was almost the same. Her eyes were grey and almost as big as his own, but you could hardly see them through the curtain of hair. They were like headlights glaring through fog. Even her lips were colourless. Bug wondered if she had any blood at all.

Gurl clutched the cat close. “She’s not your cat.” Her voice was low and sort of scratchy, as if she didn’t use it much.

“Sure she is,” said Bug, getting to his feet. “I found her.”

She tried again. “This is the girls’ dorm.”

“No, this is the hallway.”

“This is the entrance to the girls’ dorm. You have to leave.”

Bug laughed. “You gonna make me?”

She gripped the cat tighter in her arms. “You can’t tell anyone,” she said.

“About what?” He looked down at his mangled knuckles, red and scraped from punching the walls. She saw them too and took a step back.

“You can’t tell anyone about the cat.”

“Why not?”

“Because!” the girl blurted. She looked as if she might burst into sloppy tears, which just made Bug think of an even better name for her: Dishwater. Weepy Dishwater Pasty Face.

“She’s mine,” said Bug. “She chose me.”

“She did not!”

“She did too! She was rolling around with me. You saw her.”

“That’s doesn’t mean she chose you,” said Gurl. She seemed to think a minute and then she said, “Listen, Chicken—”

But Bug cut her off. “Don’t call me Chicken!” he shouted, punching the wall. “That’s not my name!” Wham! “I have a real name.” Wham!

The girl took another step away from him. “OK, OK,” she said. “Sorry, what’s your name?”

“What do you think?” he said, opening his eyes as wide as he could. “It’s Bug.”

The cat began to wriggle and struggle in the girl’s arms until she was forced to let it go. “See?” Bug told her. “She wants to come back to me. She plays a mean game of rolling pin.”

But the cat trotted past both children and strode into the bathroom at the other end of the hallway. Bug followed, the pasty girl on his heels, but the cat ran behind the door and pushed it shut.

“What’s she doing?” Bug said, pressing an ear to the door.

“She’s fine,” the girl told him. But she seemed just as confused as Bug was.

After a few minutes, they heard the toilet flush.

“Come on!” said Bug. “Cats use toilets?”

“Of course they do,” the girl said, obviously surprised as well. Soon they heard the sound of water splashing in the sink. “Anyway, you can go now. I’ll catch her when she comes out.”

“No, how about you can go and I’ll catch her when she comes out,” Bug said. Not only was the cat rare, it was some sort of super-genius, toilet-flushing cat. Maybe she could fetch! Maybe she could balance pineapples on her nose! Maybe she could juggle chipmunks! He wasn’t going anywhere.

“She’s not yours!” the girl hissed. Suddenly, she got paler—if that was even possible—and her grey eyes went all silvery, like two nickels. Quickly, she pulled the sleeves of her red sweatshirt over her hands.

The girl was weirder than everyone said she was. “What’s wrong with you?” Bug said.

“What’s wrong with who?” said a voice. Mrs Terwiliger glided down the hallway. “Chicken! I’ve been looking for you. What are you two doing loitering near the girls’ dormitory?”

“Nothing,” Gurl and Bug said at once.

Mrs Terwiliger’s eyes narrowed, staring down at them both. “Gurl, you look pale,” she said, sounding more accusatory than compassionate. (And she enunciated the word “pale” with so much force that she spat.)

“I’m just tired,” croaked the girl. “I think I need a nap.” She tugged at the sleeve of her sweatshirt again. Was it Bug’s imagination or did the sweatshirt seem to be fading somehow? It had been red, but now it looked pink. And there was a faint pattern in it that he hadn’t noticed before, like the lines in a brick wall. Just like the painted brick of the hallway.

Mrs Terwiliger’s overwide lips turned down at the corners and Bug wondered if she had noticed the same strange things. But all she said was, “A nap is a wonderful idea. Go.” She waved her bony hand and Gurl practically ran into the girls’ dorm.

Then Mrs Terwiliger crooked a finger at Bug, the fluorescent lights shining off her tight, waxy skin. “Come, Chicken. Instead of punching the walls, I’d like you to help me move a filing cabinet. There’s a good boy!”

She turned and floated off. Bug started to follow, peeking inside the open door of the girls’ dormitory as he passed. And that’s when he saw her. Uh, didn’t see her. Because the girl wasn’t there. The room was empty.

Bug opened his mouth to shout—because what else do you do when a weird, weepy girl ups and totally disappears?—but then he thought better of it. Something extremely funky was going on with Pasty Gurl, but he’d keep his mouth shut.

That is, he would keep it shut in exchange for a certain toilet-flushing, rolling pin-playing, very rare, genius cat.

“Chicken!” said Mrs Terwiliger. “Move it along!”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, a sly grin on his buggy face. “I’m moving it as fast as I can.”