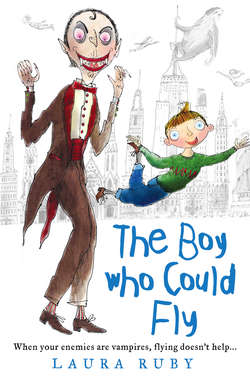

Читать книгу The Boy Who Could Fly - Laura Ruby, Laura Ruby - Страница 11

Pinkwater’s Momentary Lapse of Concentration

Оглавление“Are all you brats just going to stand there? Aren’t any of you going to see if she’s alive? Oh, never mind. Hello! Are you all right?”

Georgie opened one eye and peeked out through the pile of bones. It wasn’t Ms Storia. A stunningly beautiful girl with olive skin and white wrap on her head stood looking at her. Hewitt Elder, the senior chaperone.

Georgie tried to climb out of the pile. The tibia of the giant wombat rolled off her shoulder and landed on Hewitt’s foot.

“Sorry!” Georgie said.

A muscle in the girl’s cheek twitched, but otherwise she made no other movement. “Are you injured?” she said stiffly.

“Um…” Georgie flexed her arms and legs. “I don’t think so.”

“So nothing’s broken?”

Bethany Tiffany snickered. “Nothing except the entire exhibit,” she said.

Hewitt Elder ignored Bethany. “Next time, watch where you put your feet.” She glanced at Roma Radisson. “There are people in this world who enjoy tripping you up.”

“I’ll remember that,” Georgie said. The beautiful girl turned and walked away, moving so gracefully that she appeared to be flying, but she wasn’t. Georgie wished she could move like that. She wished she were small and graceful and beautiful enough to wear a wrap on her head instead of being huge and pale and clumsy enough to take out a mega marsupial.

Roma put her hands on her hips as she watched the beautiful girl walk away. “Who does she think she is?” But she didn’t say anything directly to Hewitt. Something about Hewitt cowed even Roma Radisson.

Ms Storia, who had been busy apologising to the museum employees because of her destructive student, marched to Georgie’s side. “Girls, the excitement is over now. Let’s get moving.” She hissed in Georgie’s ear, “Please be more careful next time!”

Georgie said nothing, the shame overwhelming her vocal cords. She waited till the last giggling, snickering, laughing Prince School girl passed her. Then, after ducking behind the nearest skeleton, she vanished.

Literally.

As soon as Georgie was invisible, relief flooded through her body. This way she could visit any exhibit she wanted without having Roma calling her a monkey or a marsupial or whatever else came into her vicious Dunkleosteus brain. And Ms Storia would be so busy being fascinated by all the sights in the Hall of Flight and so busy sharing that fascination with the girls of the Prince School, she’d never notice that Georgie was missing.

As she strolled the near-empty Advanced Mammals gallery, she did feel the merest, slightest twinge of guilt. Her parents had let her attend school on one condition: that she never use her power of invisibility in public. But, she told herself, this was an emergency. Her parents couldn’t expect that she wouldn’t use her power in an emergency. They wouldn’t want her to be humiliated by Roma Radisson, Walking Dunkleosteus. They wanted Georgie to be normal. They wanted Georgie to be happy.

And, looking at a skeleton of a sabre-toothed tiger, she was happy. There was something soothing about literally fading into the woodwork. No one to stare at her ridiculous mop of silver hair. No one to see her trip over her own feet. No one to ask her “How’s the weather up there?” and giggle as if that was the funniest thing anyone ever said. Nobody taking pictures of her when they thought she wasn’t looking because her parents happen to be The Richest Couple in the Universe. No one gaping—

—a little boy was gaping. But he couldn’t possibly be gaping at her, because she was invisible. And there was nothing else close but the sabre-toothed tiger. It’s OK, she thought, he’s just afraid of the tiger.

“Mummy?” said the boy in a quivering voice.

His mother, a largish woman in stretchy green trousers who was examining the skeleton of an ancient horse, said, “What, honey?”

“Mummy, look!” He tugged on her trouser leg. He had large brown eyes that seemed to grow larger by the second.

“What is it?”

“There’s a nose!”

“What did you say?” said his mother.

“There’s a nose floating in the air. Right there!”

“Oh my!” said the woman, clapping her own hand over her mouth in shock.

Oh no! thought Georgie, clapping a hand over her face.

Georgie fled the Advanced Mammals gallery, the woman’s shouts following her all the way down the stairs and through the Hall of North American Birds. She didn’t stop running until she reached the State Mammals gallery. Breathing heavily but trying not to, she lifted her hand and peered at her reflection in the glass of a display. There it was, as clear as the poor, sad stuffed bobcats behind the glass.

Quickly, she focused all her energies: I am the wall and the ground and the air I am the wall and the ground and the air I am the wall and the ground and the air… She looked into the glass again. Her nose was gone, just the way it was supposed to be.

What was that about? she wondered. Then again, she hadn’t disappeared in more than five months. And it’s not like anyone had ever explained invisibility. It’s not like there was anyone who could, except maybe The Professor, and she hadn’t seen him since Flyfest in November. She never understood how it worked, why her clothes disappeared with her, why objects or people she touched did too, but not, say, whole houses when she touched the walls. She’d brought these things up with her parents, but they never wanted to talk about it. They warned her against experimenting with it, as if the power of invisibility was some sort of weird itch one had to try not to scratch, like eczema or chicken pox.

She sighed and poked around the State Mammals Hall, which displayed the state’s most common mammals in dioramas. She studied the porcupines, hares, and shrews but swept right by the bats. (She heard enough about flying without having to see the bats.) She turned the corner to the next hall, where she caught her foot on a metal radiator, which might not have been a problem except that she was wearing open-toed sandals.

“OW!” she shrieked.

A family of four who had been waiting for their turn at the water fountain looked in her direction, then all around the hall. “Did you hear something?” the father said to the mother. “I thought I heard something.”

Georgie staggered away on her mangled foot, making it all the way down the stairs and out the front door of the museum before realising that perhaps this wasn’t the best idea. It was one thing to defy her parents about the invisibility thing – even though this was clearly an exception to the rule, being an emergency and everything – but it was another thing to skip out on a school trip. You have to go back, she told herself. You have to find some private place to reappear and then you have to go back to Ms Storia’s group and be appropriately fascinated by all the fascinating things at the museum. Just like any normal girl on any normal day.

Except she wasn’t a normal girl. And nothing was going to make her one.

So, instead of rejoining the girls of the Prince School, Georgie limped home. She’d forgotten how much she liked wandering (er, hobbling) the city streets unnoticed. It was spring, and people were springing: some hopping, some floating, some zipping along on flycycles, a few walking. And of course the birds were out in force along with their owners – mynahs, parrots, budgies, cockatoos – all flying lazily on thin rope leashes.

She approached her building and saw the tall and grave-looking new doorman standing at the door – Dexter or Deter or something. Georgie crept by him and slipped into the building after crazy old blue-haired Mrs Hingis. She waited until Mrs Hingis had been swallowed up by one of the lifts before catching the other one up to the penthouse. When she was safely on the top floor, Georgie reappeared, making sure to account for every single body part – even turning around to check to see that her bum wasn’t missing. Then she opened the door and walked inside. The Bloomingtons’ penthouse had windows that served as walls and high cathedral ceilings that made a person feel as if they weren’t living in a house as much as living on top of a mountain. Even now, even after coming to this penthouse for months, she was shocked that it was her home.

“Hello?” Georgie said. “Anyone here?”

“Hello!” Agnes the cook boomed. “Who is there?”

“The President of Moscow!” Georgie hobbled into the kitchen.

Agnes was cutting potatoes while watching the tiny portable TV she kept on the counter. “Russia is country. Moscow is city. Moscow can’t have president.”

“I know that, Agnes. I was just kidding.”

“Kidding?” said Agnes, as if such a thing was a foreign concept. The Polish cook put down her knife, scooped up a dish towel and snapped it at the open window, where a crow sat staring. “Shoo!” she said. “Go home!” She returned to her chopping block, muttering, “Nosy.” She frowned at Georgie. “What’s wrong with you?”

“What do you mean?”

“You look very bad.”

“Thanks,” said Georgie. “I work at it.”

“What’s that? More kidding?” said Agnes. She wiped her hands on a towel and opened the refrigerator. She pulled a plate full of Polish sausage and a jar of purple horseradish out of the fridge. Then she cut several slices of sausage and arranged them on the plate with a spoonful of the horseradish. “You eat. Horseradish clean out your head.”

“My head is fine,” Georgie said.

Agnes shook her own head. “Your head is not good. You do funny things.”

“What do you mean?”

“I have to say?” Agnes said. She pursed her bow lips. Agnes was very small and pretty, with fluffy blond hair down to her shoulders. She would look much younger, Georgie was sure, if she didn’t wear baggy men’s jeans and oversized football jerseys. But no matter how weird her outfits or sense of humour, Georgie would never think of making fun of Agnes because Agnes knew things. She knew when Georgie was hungry and when she was full. She knew when Georgie wanted company and when she wanted to be left alone. Georgie thought that if she were to turn herself invisible, Agnes would be able to see her anyway.

“Agnes?”

“Hmmm?”

“Are you my Personal Assistant?”

Agnes frowned. “I am cook.”

“Well, yeah, but are you my Personal Assistant, too? You know, kind of like a fairy godmother? Or father? I had one named Jules once, and I thought he’d come back. But maybe you were sent…” Georgie trailed off, realising as she spoke that she sounded completely nuts.

“Never mind,” said Georgie. “What’s on TV?”

Agnes shrugged. “News,” she said. “Not much news on news.”

Georgie turned up the TV. An overly tanned man with blinding white teeth and what looked like plastic snap-on hair said: “And in other news, the American Museum of Natural History reported the theft of the remains of a colossal cephalopod. Try to say that ten times fast. Heh. Ahem. Apparently, a scientist was working on them in his lab, turned his back, and the remains disappeared. The cephalopod, a giant octopus, was the largest specimen scientists had ever discovered. It is estimated that the octopus might have weighed more than a hundred kilos when alive and had limbs more than six metres long. Whoa! Wouldn’t want to meet that in a dark alley, ay, Bob? Heh.”

“This guy is stupid,” said Georgie.

Agnes grunted. “He should eat horseradish.”

“Here’s our entertainment reporter, Katie Kepley. Katie?”

“Thanks, Mojo. Well, here’s the question that’s on everyone’s mind: Is Bug Grabowski bugging out?’”

“Bug?” said Georgie. “What’s wrong with Bug?”

“It appears that Sylvester ‘Bug’ Grabowski had a mental breakdown and threw himself into the East River at a photo shoot this morning. Though he claims some sort of sea monster pulled him into the water, renowned fashion and advertising photographer Raphael Tatou disputes the story. ‘There was no sea monster,’ said Mr Tatou. ‘Only a very difficult child playing games and wasting everyone’s time. Or maybe he was having an attack of nerves, I don’t know. All I know is that I’m a professional, and I want to work with professionals.’”

Pictures of a wet and dishevelled Bug flashed on the screen. “Hey!” said Mojo the news reporter. “Maybe it’s the giant octopus.” Katie Kepley giggled her signature giggle.

Agnes tsked and waved her knife. “Too much funny stuff for horseradish. Need something else.”

“What? Like pierogi?”

“No,” Agnes said. She thrust the handle of the knife at Georgie. “Chop. I be back.”

Agnes swept out of the kitchen. Georgie sliced potatoes until Agnes returned. Carrying a birdcage. With a bird in it. Noodle stopped batting the bit of sausage around the floor and stared at the cage.

“What’s that?” Georgie asked.

“Elephant,” said Agnes. “See? You not only kidding person.”

“What am I going to do with a bird? Noodle will eat him.”

“Bird is not for cat or for you,” Agnes said. “Bird is for Bug. You bring.”

Georgie looked at the TV screen, at the pictures of Bug, drenched and bedraggled and sad. She thought of the last time she saw Bug, how awkward she felt. “I don’t want to see Bug,” she said.

“Too bad,” said Agnes. “He wants to see you.”

“He does?” Georgie peered in at the bird. “Does it have a name?”

Agnes reached into her pocket and pulled out some sort of official-looking certificate. She handed this to Georgie.

“‘Pinkwater’s Momentary Lapse of Concentration, CD, Number Fourteen,’” Georgie read.

Agnes nodded. “Purebred for bird show.” Deftly, she sliced the last potato and put the slices in a pot. “But bird not blue enough for show. Or something stupid like that. What I know?”

Footsteps echoed in the huge penthouse and Georgie’s mother, Bunny Bloomington came into the kitchen laden with bags. “Georgie! I thought I heard your voice,” she said. “What are you doing home so early? And when did we get a bird?”

“Wombat!” chirped Pinkwater’s Momentary Lapse of Concentration.

“What?” said Bunny.

“The wombat exhibit was, um, broken, so the tour was a little short. They sent us home. The bird must have heard me and Agnes talking about it. He’s for Bug. I’m going to bring it to him later.”

“That’s so thoughtful,” Bunny Bloomington said. “Well. It’s too bad that your very first school trip was cut short, honey.”

“Oh no. I wanted to come home.”

“Why?” said Bunny, instantly concerned. “Is anything wrong? Aren’t you feeling well?” When Georgie first came back to live with her parents, Bunny got more and more terrified she might lose Georgie again, that someone might kidnap her and take her away. After a while, she didn’t want to let Georgie out of her sight. Now it seemed that Bunny was calming down again, but she was still more nervous than the average parent of a thirteen-year-old. Which meant she was still very, very nervous.

“Nothing’s wrong, Mum,” said Georgie. “Everything’s great.”

Bunny unconsciously clutched at her heart. “Oh, I’m so glad. You know, I wasn’t sure about sending you to school. I would have been much more comfortable with a private tutor. I still would. But it does seem as if you’re having a wonderful time.” She studied Georgie’s face. “You are, aren’t you?”

Georgie forced herself to smile. “I am, Mum, I swear. If it was any more wonderful I would probably have to be hospitalised for over-joy.” She kept her lips peeled away from her teeth till her mum beamed back at her.

“I knew everyone would just love you. How could they not?”

After Bunny swept out of the room, Agnes shook her head. “Stop with that fake smiling. You’re giving me creeps.”

“You mean I’m giving you the creeps, Agnes.”

“Yes,” Agnes said. “Those too.” She thrust the cage at Georgie. “You bring Bug. He need friend.” Those sharp eyes appraised Georgie. “And so do you.”