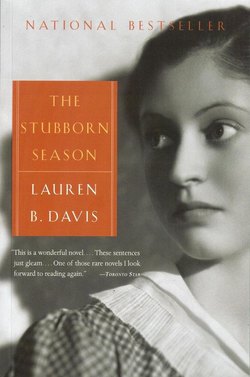

Читать книгу The Stubborn Season - Lauren B. Davis - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

9 October 1930

ОглавлениеIt was Wednesday evening and Douglas sat listening to the Palmolive Hour on the radio with his vest unbuttoned and a cup of tea on the small table by his chair. He looked so smug and content, Margaret wanted to smack him.

Margaret had shooed Irene off to bed early. All through dinner her nerves were so on edge she feared she’d bite through the fork. Douglas thought he was hiding the extent of their money problems from her, but he wasn’t. The first hints had come a few weeks back, when he began complaining about little things she bought.

“Do you really need new handkerchiefs, Margaret? And more gloves? Surely you have a drawer full of gloves.” He had stood in the doorway of the bedroom, with his hands in his pockets, jingling his keys, watching her fold her purchases and put them in the dresser. “For someone so very fond of pointing out how difficult times are, you certainly seem to be selective about where you economize. I don’t mean to scold, my dear, not to scold at all, but merely to draw attention to how important it is not to live above ourselves.”

“Above ourselves? What are you talking about? I’m the one who’s scrimped and saved and done without while you waste your money on booze. You’ve got your nerve, mister.”

He had looked blankly at her and turned heel.

Now, in the living room, Margaret said, “I went into Mrs. Munsen’s today.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Yes, I had quite a chat with her.”

“That’s good, my dear. You should get out more often.”

“I wanted to buy some cloth, to make dresses for Irene and me.” She began to scratch the back of her hands without noticing she was doing it.

Douglas continued listening to the music on the radio.

“You can imagine my surprise when she wouldn’t take our money.” Margaret had the satisfaction of seeing his head snap around to look at her. She could hear the bones in his neck crack. He picked up his tea cup and took a sip.

“What do you mean?”

“I think you know what I mean.”

“If you have something to say, Margaret, then say it.”

Remembering the scene in the yard goods store, she was embarrassed all over again. “Yeah, a fine cloth. Blue suits you fine,” Mrs. Munsen had said, her arms waggling as she folded the cloth. “But you put your money away, missus. We owe your husband a penny or two. Not all the world’s as kind as him.”

“You’ve given them credit, haven’t you?” Margaret said, and heard his startled little gasp. “I had to stand there and hear about it, hear how my husband had put me in the position of having to barter, for the love of God!”

“Not me for sure, but Karl, my middle son, he’s not doing so good now that Inglis let off everybody just like that,” the woman had said, as though Margaret cared about her doltish son. “We help out where we can, but who’s got extra these days? You feed the family and it’s all gone, eh? You know how it is. Karl with the twins to feed, he’s got his hands full, and your husband, a good man him, he says you pay when you can. So you don’t pay here either, missus. We’ll just make a note of what you take and tell the mister to set it down against what we owe. Like the old country, eh? When the newfangled ways all go to hell, the old ways are best again.”

“There’s nothing wrong with extending a little credit to a good customer, Margaret. It’s good for business, in fact. Builds goodwill.”

“I know what you’ve been doing, Douglas. I’ve seen the books.”

Douglas stood up, overturning his tea cup.

“Douglas! Be careful!” Margaret knelt and mopped at the tea with her apron.

“Do not tell me, Margaret, do not tell me you’ve been going through my papers!”

It had been so easy to jimmy the flimsy lock on his desk with a hairpin and a nail file.

“Oh yes, I’ve been in your precious sanctum sanctorum. You’ve extended credit to almost as many people as have paid. How could you be so stupid? When do you think anyone’s going to be able to pay? Next month? Next year? And what are we supposed to live on in the meantime?”

“You had no right!”

“I have every right,” she said, standing. “You won’t tell me things. All you say is, ‘Buy cheaper meat, Margaret. Cook with beans instead, Margaret. Do without new shoes, do without new stockings, don’t buy a magazine, can’t afford this, can’t afford that!’ ” She sing-songed the words, her hands on her hips. She felt more alive than she had in some time, the fear for their future mixed with the red-hot joy of having him dead to rights, the perverse pleasure of having her fears confirmed. “We’ll lose everything!”

“Things are not that dire.”

“Collect that money, Douglas.”

They stood facing one another, their laboured breathing the only sound.

“I’ll run my business as I see fit,” said Douglas. “Stay out of it.”

And before she could say another word, he strode to the hallway, picked up his hat and walked out, not even bothering to close the door. Margaret wanted to run after him, to scream at him in the street, but the neighbours would see and she couldn’t bear that. She stood in the doorway, all the passion of a moment before draining out of her feet onto the chilly floor. Then she slammed the door. She kicked over the chair, ran up to her bedroom, slammed that door and threw herself sobbing across the bed. Soon they would be out on the street, she knew they would be. They would starve.

Down the hall Irene turned her face to the wall and pulled the pillow over her head.

It was mid-October now, and they were blessed with a fine Indian summer. As the day ended, Douglas decided to take a long walk before going home. He was in a slightly bleary fog of whisky and goodwill toward men. He was thankful he was no longer burdened by an automobile. A brisk walk was good for the constitution. He stepped out into the lengthening shadows and took deep breaths of the muggy air. His flask rested against his heart. Although it was a balmy night, he whistled “God Rest Ye, Merry Gentlemen” and doffed his hat at ladies.

He decided to walk all the way along Queen Street, maybe as far as University, even up to Queen’s Park and then back along College to home. He strolled along, pleased with himself and the world. As he rounded the corner of Bay and Queen Street he came upon a group of perhaps twenty-five men and five or six women. They were a ragtag group; even in his jolly mood he could tell that. They were lean and serious. The man in front of him wore pants so thin in the backside they were barely decent.

Douglas did not like crowds, especially not crowds of dingy men and especially not on an evening when he felt so full of fellow-feeling. He tried to pass, but he was slightly unsteady on his feet, and someone bumped into him. A man reached out a steadying hand, and Douglas saw that the knuckles were covered in scabs.

“Whoa there, pal,” the man said, his voice friendlier than his hard-luck face. “Steady,” he said and smiled.

“Fine,” said Douglas. “I’m fine.”

“Course you are. Can’t blame a man for taking a snort to make hisself feel better in times like this.” The man looked around and then leaned into Douglas, speaking softly. “Don’t suppose you’ve got a taste thereabouts yer person, do you? For a pal?”

“Certainly not,” said Douglas. He brushed imaginary crumbs from his lapels.

“Ah well, too bad, eh?” said the man.

Douglas was gently jostled into the centre of the crowd. Finding himself surrounded, he thought he might as well listen. No doubt some Methodist preacher calling on the Lord to bring on Armageddon. It might be amusing.

A young man stood on a crate, head and shoulders above the crowd. He was pale and wiry, and didn’t look like he’d be much good at anything that didn’t involve a desk and a stack of paper.

Douglas couldn’t follow the man’s words. He said something about the capitalists and how they didn’t care about the working man, who was starving for lack of food and atrophying for lack of work. He waved his hands about a great deal.

“Now Tim Buck, he’s a man with a difference, let me tell you. He’ll not sell you out the way the Tories have, the way the so-called Liberals have. He’s a man who cares, is Tim Buck. You support him and he’ll support you!”

The man next to Douglas nudged him. “That there’s Tom McEwen, and the guy behind him”—he pointed to a small, clean-cut young fellow who looked like a department store clerk—“that’s Tim Buck. Great man. We’s here for Tim Buck, eh? All of us. Ain’t gonna put up with this no more. Not no more.”

Douglas’s head began to clear. There had been newspaper reports of this Tim Buck, a Communist. A rabble-rouser. A threat to the Dominion.

“Let’s hear it for Tim, friends! Tim Buck!”

“Excuse me,” said Douglas, starting to push through the cheering crowd. He did not want to be among Communists. Methodists were bad enough. He was too hot now and didn’t feel well. He stuck out his elbows.

“Hey, watch who you’re poking!” someone snapped.

“Sorry,” said Douglas and tried to move forward.

“Oh, Jesus,” said someone else. “It’s the cops!” The crowd became very quiet, everyone looking this way and that. The police had come off a side street and were upon the group before they knew it.

“We’ll fix you sons of bitches.” Several policemen shouldered their way through the crowd with far more success than Douglas, who was hemmed in on all sides. Over the top of people’s heads he could see uniformed riders on horses.

“We have every right to be here. You have no legal reason to stop this meeting,” said McEwen. Tim Buck stood at his side, his arms folded across his chest.

People began to mutter about their rights, but there was a hum of fear. A man grabbed a woman’s arm and said, “Let’s get the hell out of here.”

More blue uniforms pushed through, their batons held out in front of them. The horses pranced nervously, their chests thrust out, driven forward by their riders, and people in front of them held their hands up, trying to quiet the animals and keep out of their way.

“This is a lawful street meeting!” McEwen called out.

“Shut that bastard’s mouth!” yelled a policeman, and with that, another cop, thick-limbed and stocky, raised his elbow and used it to abruptly close McEwen’s mouth.

In that instant people started running and truncheons began to fly. The man who had asked Douglas for a drink cowered in front of a mounted cop. He threw his hands up over his head and screamed, “Don’t hit me, I’m an anti-Communist!” The cop cracked him on the back with his baton and said, “I don’t care what kind of Communist ya are.”

Douglas turned to his left and his right, pushing people who were backing into him. He found his path cut off in every direction and he pushed backwards, only to feel hands roughly upon him.

“Right then, Mac. Into the van with you,” said the cop.

And although he protested that he was not a Communist, he was an Anglican, this only made the beefy man laugh. Douglas found himself in the back of a urine-rank paddy wagon with McEwen and Buck and several others. Three men bled from wounds to the head or face. One man’s nose was broken and he cupped his hands against it gingerly as blood dripped onto his shirt.

“I’m not a Communist,” said Douglas, looking from one man to the other.

“You are now, friend,” came a voice from the corner. “Tom McEwen’s the name,” he said, extending his hand. “Welcome to the Great Repression.”

Where the hell was Douglas?

Margaret smoked one cigarette after another and practised sending smoke rings into the sticky air. She got up now and again to check whether the telephone was working. She fiddled with the radio dial, listened to Chick Webb and his orchestra live from the Savoy Ballroom. At ten she turned to CPRY to hear Fred Culley and his Dance Orchestra. When that was over and the newscast began, she turned the radio off with a snap.

Where the hell was Douglas?

A month ago he had been brought home by Mr. Steedman, a soft-spoken church-going man who lived with his wife and two small sons three doors down. Mr. Steedman had had to prop Douglas up in the doorway to make sure he didn’t fall while he rang the bell.

“Just about made it home, Mrs. MacNeil. Found him asleep in his car at the end of the block. I thought for a moment he might be hurt, but, well, looks like he’ll be fine.” Mr. Steedman smiled. He had a wide, handsome face, clean and honest. He looked sorry to be embarrassing her this way.

“You’re very kind to bring him home.” Margaret threw Douglas’s arm around her shoulder and began to wrestle him through the door.

“Hello, there,” Douglas had slurred. “It’s the little lady. Ain’t she pretty? Prettiest girl . . .”

“I can’t tell you how embarrassing this is.”

“No need to say anything,” Mr. Steedman said. “I’ve been known to tie one on myself. Do you need any help? I could help you get him to bed.”

“Thank you, you’ve done enough. I can handle it from here. Thank you.” She closed the door.

“You idiot! Out there for all the neighbours to see. You’re a disgrace.” She had plopped him in a chair and left him. The next morning he woke with a neck so stiff he could barely lift his throbbing head.

“Serves you right,” she said, and she hid his car keys.

She had wanted him to ask about the keys, wanted him to beg her forgiveness. But he only said, “Margaret, have you seen my keys? I have to get the car.”

“I’ll be getting the car, Douglas. And keeping it until you can prove you’re fit to drive it.”

“Suit yourself,” he’d said. “Gas is too expensive anyway.”

A week later he brought a man home after work. Douglas sold their Ford to him for $200. Walked into the kitchen smug as a feudal lord, riffling the money in the air like a fan. What he had done with the money she had no idea. She certainly never saw a penny.

If he was out squandering what little money they had left, she’d bash his brains in with the marble pastry pin. They’d never again brought up the subject of the credit he was giving out. She thought her silence might have pried some words from him, but there had been none.

She climbed the stairs and went into her daughter’s bedroom. A path of light fell across Irene’s sleeping form. Margaret reached into the pocket of her housecoat and pulled out her tin of cigarettes and her silver lighter. She lit one, and then snapped the Zippo shut. Irene didn’t stir at the sound.

“Sleeping, baby?”

Irene did not respond.

Margaret was about to sit down on the edge of the bed when she heard footsteps on the porch. She whirled toward the sound and rushed from the room.

As soon as Irene heard her mother’s footsteps clattering down the stairs, she opened her eyes, just peeking through half-closed lids at first and then opening fully, staring fixedly at the point where her mother had been.

Douglas climbed the porch steps slowly. His feet felt encased in shoes of cement. He had spent the past several hours in a cell at the police station on College Street. It was a malodorous concrete space, crowded with men. Some smoked cigarettes and two played cards. One of these card players was a red-skinned Indian man. He was huge, at least 300 pounds, with jet black hair cut so close to his head that Douglas could see the multitude of scars on his scalp. He played some game that Douglas didn’t understand and every time he snapped a card down on the pile in front of him, yelled “Shoot the dog!” and his partner laughed. Others hunkered against the wall, their eyes as flat as tin plates, giving away nothing. One man, the front of his pants stained dark with what Douglas’s nose told him was urine, slept in a corner, his snores phlegm-filled.

Douglas sat primly on the edge of a bench near the bars where the air, he imagined, was slightly fresher. He remained very still, careful not to draw attention to himself, for who knew what these men would do if they knew just how little he belonged to their tribe. Only the conviction that they could turn on him at any moment, like hyenas tearing at the stomach of a weakened pack-mate, stopped tears from lining his cheeks. He willed himself not to pull the hem of his jacket away from the man beside him and thereby betray the intensity of his disgust. He sat still and silent and hoped this passed for assured self-containment.

He wanted to tell the police that it was a mistake, that he was not a Communist, but no one seemed to care. When he had been brought into the station, herded up to the desk and told to empty his pockets, he had tried to explain but was told to shut up and do as he was instructed. A hand had grabbed him roughly by the upper arm, and Douglas had been shamed by how scrawny his own arm must feel under such strong fingers. It made him aware of how weak he was and how vulnerable and he then became afraid not only of the men with whom he was arrested but also of the police themselves.

After they had clanged shut the heavy, barred cell door, the police brought in McEwen and began to taunt him, telling him they would take care of his kind. That they knew what he was up to. That he should go back to where he came from. McEwen said he was born right here in Canada and had a right to his beliefs. That he was a member of a legally recognized political party and that the police had no right!

A policeman had silenced him with a punch to the stomach. Douglas watched, horrified, as they beat him to a bloody pulp. McEwen kept his hands over his ears, his elbows shielding his face, until he became unconscious. Douglas thought they would stop the beating then, but they did not. They kept right on kicking him in the ribs and the back and the legs. What shocked Douglas almost as much as the beating was the fact that the police did not even try to hide what they were doing.

All the muttering, all the shouting, even the snoring in the cell had stopped.

When they were finished, they threw McEwen, nothing more now than a sack of sharp bones and lumpy, multicoloured flesh, into the cell.

And now he had to face his wife. He wondered which would be worse, but then shivered this thought away, because to joke about it, even to himself, was a betrayal to McEwen, a man he didn’t know, didn’t want to know, but to whom he felt he owed something.

Douglas drew a deep breath, ran his hand along the top of his shiny head and opened the door to his house.

“Where have you been?” Margaret was disgusted at the sight of him. “You’ve been drinking!”

Douglas moved past her, not quite pushing her but coming close enough to give her a heart-hiccupping start. She opened her mouth to say something, but then closed it again when she found no words ready. Douglas hauled himself up the stairs and disappeared into the bathroom. Margaret heard water running.

As she approached the bathroom door she made her hands into claws. She’d go right through the door if she had to.

Inside the clean space of the bathroom, Douglas looked at himself in the mirror over the sink, his face framed within the ivy pattern of the wallpaper. Behold the conquering hero, he scoffed at himself. Shock provided a window of weird objectivity, and it was through this portal that the sagging lines and pouches and rabbity eyes told the truth of who he was. Before this night he had believed himself to be no more or less brave than the average man. But now the truth was revealed. He was a coward.

The scene played over in his head like a newsreel.

He couldn’t tear his eyes off the terrible spectacle of the man lying on the cold concrete floor, his face swollen and bloody, his left eye so puffed up it looked as though some parasitic creature had attached itself to his face. His shirt was hiked up, and Douglas saw the evidence of the beating: marks quickly going from red to purple, blood drying on boot-shredded skin. The men gathered close.

“Leave him alone,” said one.

“See if you can wake him,” said another.

“Should we try and get him on his feet?”

“Bastards did him in but good.”

McEwen moaned and stirred, his arms and legs twitched. His eyes flickered open and then closed. A trickle of blood leaked from his mouth.

“Looks like he’s lost a tooth or two,” said a man with no more than three teeth in his head himself.

“Shoot the dog,” said the big Indian, quietly, although what he meant was unclear.

McEwen made a wet sucking noise in his throat. He tried to push himself up on his elbows.

“Get him sittin’ up,” someone said.

“Perhaps we could lean him against the wall,” Douglas said, and when eyes turned toward him, he pointed. “That wall, maybe.”

Pairs of hands heaved the limp body into a seated posture against the wall. McEwen’s head sagged on his breast and a string of pink-tinged drool stained his already filthy shirt.

With the injured man settled, the rest went back to their conversations, their pacing back and forth, their smoking, their cards, although now and then they glanced discreetly in McEwen’s direction, as though to make sure he was not about to leap on them, or fall, or die. They acted as though the violence might be contagious, and Douglas was not so sure they were wrong.

Douglas resumed his post near the bars. He didn’t like to think about what was happening to the other man, Tim Buck, who along with McEwen, had been culled from their lot upon arrival.

It was very hot in the cell and sweat trickled between his shoulder blades and between the cheeks of his buttocks, places where he could not reach. The lining of his stomach felt ragged. He vowed that should he get out of this unharmed, he would never drink again. His muscles, cramped from tension, began to tremble. His shoulders began to shiver. He crossed his arms and tucked his hands beneath his soggy armpits, praying that the shaking would stop and that no one would see his fear.

He heard a terrible retching. McEwen, clutching his stomach, was going to be sick. His head lurched, and men scattered. He tried to get up on all fours, then gave up and leaned over on one arm. He vomited blood.

The men in the cell stepped over each other trying to get out of the way.

“Guard! Guard!”

“Get a doctor!”

“Jesus H. Christ!”

Douglas was pinned against the bars. He turned his face away. A young cop approached the cell.

“What the hell’s the racket in here?”

“I think that man is going to die,” said Douglas in a voice that he did not completely register was his.

“Goddamn it!” said the policeman. “Dan! Jack! Get over here!” Other policemen came running and the door was opened. Men were pushed out of the way. Douglas saw McEwen, held under the arms and knees, being carried out of the cell. His head was tilted back. Douglas thought, He’ll choke. The man will choke.

“His head,” he said. “Be careful of his head.”

“Mr. MacNeil? Is that you?” A hand touched his shoulder. “What are you doing with this bunch? How did you get here?” said a dark-haired young cop. “Are you okay?” The young man waved his hand in front of Douglas’s eyes.

“I’m not a Communist,” said Douglas.

“What the hell are you doing in here?”

“I know you,” he said.

“Of course you do. I’m Bobbie Patterson.”

Yes, that was it. He was little Bobbie Patterson. One of the boys who stole candy from the counter and mussed up his magazines. One of the neighbourhood boys Douglas had chased out of the store for years. He reached up and put his hands on Bobbie’s shoulders. He was afraid he might cry.

“I was walking. There were all these people. I wasn’t one of them. I was just walking.”

Bobbie Patterson pulled back and Douglas knew the whisky must be on his breath.

“Course you were, Mr. MacNeil. Course you were. Let’s see what can be done about this.” And he pulled Douglas from the cell, amidst hoots of derision.

“Yer a yellow-hearted fellow,” said a man. “Good riddance to ya!” And Douglas heard someone spitting.

“You know,” Bobbie Patterson said as they walked down the long loud hall, “you should be more careful, Mr. Mac. These men in there, well, they’re a bad sort. They’re out to undermine everything we stand for in this country.”

“Oh, yes, I can see that,” said Douglas. “I’m just an unlucky bystander in all this. I tried to explain that to the other officers but they wouldn’t listen. Although,” he added, seeing a dark look cross Bobbie’s face, “I can see how they wouldn’t have had the time and all, given the situation. Ha ha. You men are doing a fine job. Yessir. A fine job.”

“You wait here. I’m gonna have a word.” Bobbie laid his finger alongside his nose and winked, then he went to talk to an older officer. The older man glanced in Douglas’s direction. Bobbie put his hand on the man’s shoulder, turned to look back himself, then mimed tipping a bottle to his lips. The other man smirked and nodded. Bobbie clapped him on the back and went behind the desk to a rack of lockers. From inside one he pulled a paper bag containing Douglas’s possessions and walked back to him, grinning.

“Okay, Mr. Mac, you’re free to go. And go straight home, huh?”

“Yes, of course, Bobbie, or should I say Constable Patterson, eh? Yes, straight home with me. It’s been quite a night, quite a night.” Douglas pumped the young man’s hand. He was in a hurry to go. He needed the night air, clean, calm night air, to fill his lungs with the scent of something to wipe out the stench of the cell.

“Just one more thing . . . ” The young man held his hand firmly and wouldn’t let go.

“Yes?”

“Well, let’s be clear here. That man who got took to the hospital. That’s a sad thing, I guess, but sometimes guys come in here all beat up, you understand. Don’t have anything to do with the police department, you understand. Wasn’t for us he’d of bled to death in that cell. You do see that, don’t you, Mr. Mac.”

“Of course,” he said, smiling, looking Bobbie straight in the eye. “Of course. Like I said, you’re all doing a wonderful job.”

“To serve and protect. That’s our motto. You have a good night, sir.” And he let go of Douglas’s hand.

Douglas fled through the doors. He emptied the paper bag and stuffed his pockets with his keys and change and stamps. The little silver flask was gone. He stood on the moon-bright street and breathed deeply. The smell of burning leaves and gasoline and sandalwood perfume from a dark-haired woman walking by filled his chest. He looked at the woman, strained after the scent and sight of her, as though she’d asked a question that was terribly important but spoken too quietly to hear. The woman wore a camellia in her hair, white as bone and pale as death.

“Douglas! You come out of that bathroom now! How dare you lock the door on me!”

The sound of her mother kicking the door made Irene want to crawl under the bed and hide. She hugged her doll, Noreen, to her chest and then the pillow too so that Noreen would be protected. Voices became Other Voices. Similar to but not exactly the voices of the people you knew. It was as though there were violent and dangerous people hiding behind the familiar faces of your mother and father, waiting to emerge at unpredictable times like these.

“Margaret, for God’s sake! Keep your voice down.”

“You dare tell me what to do! After you’ve been out whoring around town? A common drunk?”

“Shut up. You don’t know what you’re talking about. You’ll wake up the neighbours! You’ll wake up Irene!”

“It’d be good for her, to see what kind of a father she really has.”

“Margaret, I’ll not have this, do you hear. Get control of yourself.”

“Keep your hands off me. Don’t you ever touch me again!”

Her mother’s voice was completely gone now, replaced by the Other Mother, the woman who came and went inside her mother’s skin. Sometimes you could tell just by looking at her; sometimes you had to hear the voice. The voice of the Other Mother was full of spit and sour with no laughter and no way to make her see you as you really were. Irene wondered what her father would do. He was as big as the Other Mother, bigger even. If Irene was bigger she would stop the Other Mother. Put her hand over her mouth and make the words stop coming out until the Nice Mother came back. Irene hugged her knees and held Noreen tightly.

Shadows crossed the threshold of her doorway and she closed her eyes, held her breath. Irene heard her parents descend the stairs. There was a cast-iron heating vent in the corner near the door. The words came through as clearly as if her parents had been standing in her room.

“You tell me, Douglas, you tell me right this minute. Who is she? Who’s your little floozy?”

“I don’t know where you get these ideas, Margaret.”

“Oooh, don’t you take that tone with me! I’m not the one who’s out gallivanting all over town.”

“No one is gallivanting. I worked late. I had a drink. I fell asleep over the accounts. There’s no sin in that.”

“You coward. You’re going to add lying to everything else? A real man would stand up and admit what he’s done. He’d take the consequences with his shoulders squared. But not you, oh no. Not the sorry excuse for a man I married. Tell me who she is!” The voice rose to a shriek and Irene covered her ears with her hands. She pushed back in bed until she was in the corner.

There was a momentary silence and Irene held her breath.

“That’s quite enough now,” said her father.

Irene let the air out of her lungs. It would be all right now. Irene was very good at reading voices. She didn’t have to even see her father to know what he was trying to do. His voice was reasoning, calm, a little afraid. She knew what that felt like. You had to be careful here, when the Other Mother was so close to the edge of the dark place.

“You’re making yourself hysterical. I’m telling you there is no other woman. I admit I was thoughtless, I should have called.”

“I called you. You didn’t answer. You think I’m a fool. You’re laughing at me. I can see that now. I hope you’re proud of yourself. I hope you’re very proud. You’ll never be able to make it up to me. Everything is different now. Everything is very different.” Her mother’s feet on the stairs again, each step deliberate and measured.

“Margaret,” her father called softly. “Come back here. Don’t act like a fool.” Her mother kept walking. Her shadow passed as she went into their bedroom and closed the door. Irene heard the sound of a chair being put under the doorknob. Her father would have heard that too.

“Oh, for God’s sake,” he said to no one.

Irene smoothed Noreen’s sea-green dress over the doll’s porcelain legs. “Don’t be afraid,” she said. “I’m right here. I’m right here.” She knew she was too old to be talking to her doll, too old by far. “Don’t be afraid,” she said.

After a while Irene heard her father make up a bed on the couch. She lay quietly, trying to fall asleep, but it wasn’t easy.

“Good night, Noreen,” she whispered.

Douglas pressed the heels of his hands to his eyes, trying to stop the flow of tears. He lay on the chesterfield and tried to understand why he hadn’t told Margaret the truth. He tossed and turned, unable to exorcise the demons that haunted him. The smell of the unwashed prisoners, the metallic smell of his own fear, the reek of blood and urine. The implied threat in Bobbie Patterson’s words and the cold grip of the young constable’s hand. He wanted to talk to someone. He wanted to confess his fears. He wanted to confess his cowardice. He lay staring up at the ceiling, up to the room where his wife lay in their bed, from which he was banished, and deservedly so. Not because of what she thought he had done, but because of the things she didn’t know about. She didn’t know of his delight at saving his own skin, of his pathetic, salivating response to his own redemption, with nary a thought to the plight of those left behind. The tears squeezed from under his hands, rolled down the sides of his face, filling his ears, wetting his hair.

But he could not escape the horrifying fact that even though he had made the promise to God that, should he be released from the prison unharmed, he would never touch whisky again, he had no doubt he would break that promise. In fact, even as he thought this very thing, his legs carried him off the couch, down the hall and toward the closet. A voice in his head told him that after all he’d been through, it was only natural to have a drink to settle his nerves. He knew this was nonsense, but was powerless over it. He was a moral coward. In the back of the closet he found what he was looking for. He sat cross-legged in the closet and drank, and drank, and drank some more. The salt from his tears mixed with the taste of the whisky. He gave himself up to the soft warm lull and numbness of the liquor. He surrendered to it completely and drank until he had shut out the visions in his head and he could sleep.