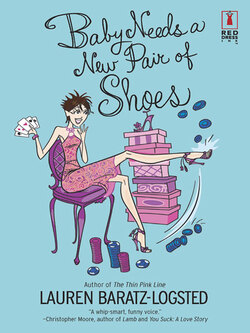

Читать книгу Baby Needs a New Pair of Shoes - Lauren Baratz-Logsted - Страница 14

5

Оглавление“No.”

“But, Dad.”

“I said no, Baby. I’m pretty sure you’re still smart enough to understand both sides of no. There’s the n and there’s the o. What’s so difficult here?”

My dad had always called me Baby, for as long back as I could remember. It was my mother, whose own name was Lila, who’d named me.

“I’m Lila,” she’d say, “you’re Delilah. It’s like Spanish. It means ‘of Lila.’”

“There’s just one problem,” I’d say right back. “We’re not Spanish. Okay, two problems. There’s that extra h at the end, which your name doesn’t have, so technically speaking—”

“Just eat your Cocoa Krispies.” She’d always cut me off right there.

My dad always claimed he called me Baby because he couldn’t stand the name Delilah. Of course, totally besotted with my mother and therefore never wanting to hurt her, despite the numerous times he’d hurt her, he only claimed that outside of my mother’s hearing.

“Do you know whom she named you after, Baby?” he’d ask, as if he hadn’t asked me the same question at least a hundred times. “She named you after the girl in that Tom Jones song! Your mother was a huge Tom Jones fan! I swear, if I hadn’t been sitting right there beside her at his concerts, she’d have thrown up her panties right there on the stage. What, I ask you, kind of name is that to give to a baby? Delilah in the song drives her man crazy, then she cheats on him, and then she gets killed for it.”

“But, Dad,” I tried again now.

“No, Baby. If I taught you how to play blackjack, Lila would roll over in her grave, and then where would I be?”

“Where you are right now,” I could have answered, “alone.”

Where my dad was right now, physically speaking, was a one-bedroom apartment in a section of Danbury just a cut above where Conchita and Rivera lived. As a professional gambler, Black Jack Sampson had enjoyed his good years (we’d once lived in a five-bedroom house even though we’d only needed two of them) and his bad years (like the last one). And, if we’re being totally honest here, he was right: my mother wouldn’t approve of his teaching me how to play blackjack. But, oh, did I want those Jimmy Choos…

“Your mother might even come back to life just to kill me if I taught you how to play blackjack,” he said.

He was probably right about that, too.

I studied my dad, a man whose personality was too big to be contained by his present tiny circumstances.

Black Jack Sampson had just turned seventy but had only just begun to look even close to sixty, his neatly trimmed salt-and-pepper hair and mustache, tall frame and lean body, combined with the fact that he always wore a suit even in summer, making him look more like he belonged on a riverboat in the middle of an Elvis Presley movie rather than with the polyester bus crew going off to play the slots at Atlantic City. Black Jack had met my mother, a schoolteacher who loved her work almost as much as she loved him, at a voting rights rally back in 1965—Lila was rallying while Black Jack made book on the side on whether the act would pass—and it had been love at first sight. He was thirty at the time and she was twenty-eight, but it had been twelve long infertile years before they’d been able to conceive a baby, me, hence the huge age difference between me and my parents, and there had been no more babies afterward, try as they might. True, these days having first-time parents in their forties wasn’t a rarity, but, when I was little, my mother looked more like a grandmother by comparison to my friends’ mothers.

Not that I’d minded.

Growing up, I thought my mother was the greatest lady who ever lived, a belief I’d maintained until the day she’d died ten years ago. And my mother, in turn, had thought my dad was the greatest man who’d ever lived…except for his gambling.

“Blackjack killed your mother,” he said.

We’d had this conversation enough times over the years for me to know he wasn’t referring to himself when he said, “Blackjack killed your mother;” he was referring to the card game.

“Blackjack did not kill Mom,” I said.

How I missed my mother! She was the steady parent, the one who didn’t suffer obsessions that worked against her. In her absence, I’d become Daddy’s Girl. But what a daddy! From my dad, I’d learned to be the kind of woman who could sit with men while they watched sporting events but nothing about what it was like to be the kind of woman men would want to do more romantic things with. I’m not complaining here, by the way, just stating.

“Blackjack did not kill Mom,” I said again. “Mom died of cancer.”

“Same difference,” he sniffed.

“Not really.”

“There was a time, when you were just a little baby, Baby, that I dreamed of you growing up to one day follow in my footsteps.”

I had a mental flash of a younger version of my dad, holding baby me in his arms and crooning, “Lullaby, and good night, when the dealer has busted…”

“We would have made quite a team,” I said. “And we still could,” I added, thinking about what becoming great at blackjack could achieve for me: a pair of Jimmy Choos.

“You don’t understand,” he said. “I promised your mom right before she died that I’d make sure you lived a better life than we’d lived, one free of the addictions that had destroyed the two of us.”

Clearly, the man didn’t know his own daughter. Me, free of addictions? Some days, I thought I’d never be free of them.

“Mom was an addict, too?” I was shocked. “What was Mom addicted to?”

He studied his wing tips, his cheeks coloring a bit.

“Me,” he answered. “Lila was addicted to me.”

“That’s not true, Dad. She wasn’t addicted. She just plain loved you.”

“Same difference.” He straightened his shoulders. “And she’d hate it if I passed the blackjack compulsion on to you.”

I thought he was making too much of this. My parents had had a happy marriage. I knew they’d been happy.

“C’mon, Dad,” I wheedled. “Wouldn’t it be great to have someone really follow in your footsteps. ‘Lullabye, and good night, when the dealer has busted’—”

“Who taught you that song?” he demanded.

“I don’t know.” I shrugged. “I thought I just made it up.”

“It just sounded so familiar there for a second.”

“But wouldn’t it be great to have me follow in your footsteps?” I tried again.

“What about poker?” he said suddenly. “Everyone’s playing poker these days. At least if you started to gamble at poker, your mother might get confused when she comes back to haunt me since poker’s not blackjack.”

I considered what he was suggesting.

Even I was aware that poker was the current “in” game and it was a game that I had some familiarity with. Back in my junior-high days, my best girlfriend and I had started a poker ring while serving an in-school suspension for getting our classmates drunk during the science fair. We’d charged a dollar a game to play and even a couple of teachers, miffed that my best girlfriend and I had taken the fall when so many others had been involved, had stopped by to play a few hands while on their coffee breaks. I think we were all vaguely aware that they could have been fired for their complicit behavior, but it was a private school—this had been one of Black Jack Sampson’s better years for winning—and we were thrilled to take their money. Besides, once the weeklong in-house suspension had ended, life at school had gone back to normal and we’d folded up the gaming table with my best girlfriend and I each about fifty dollars richer. Of course, I’d never told my parents any of this because Lila would have been too mortified while Black Jack would have been too proud, thereby increasing Lila’s mortification.

“Nah,” I finally concluded. “Sure, poker’s a trend right now, but any trend can end at any minute. Blackjack, on the other hand, is a classic. It’s eternal. And, hey, I’m Black Jack Sampson’s daughter, aren’t I? I’m certainly not Poker Sampson’s daughter. C’mon, Dad. It’ll be great. It’ll be like having the son you always dreamed of.”

It was a cheap shot to take, and I knew it even as I said it. Black Jack had always wanted a son; anyone could see that every time he tried to teach me how to hit a baseball only to have the bat twirl me around in such a big circle that I wound up dizzy on the lawn or every time he tried to teach me how football was played, keeping in mind the importance of covering the spread, only to have me yawn myself to sleep. But it was the one card I had to play, the only card that would get me what I wanted.

“C’mon, Dad. It’ll be fun.”

He ran one hand through his hair.

“You have to promise not to tell your mother about this,” he warned.

I raised my right hand. “Scout’s honor.”

“‘O, I am fortune’s fool.’”

See where I got it from? Black Jack and Lila were always quoting Shakespeare at me.

He walked out to the kitchen and I heard a drawer slide open and shut. When he returned, he had a fresh deck of red-and-white Bicycle cards in his hand. He tore off the cellophane wrapper and as he did so, he looked me dead in the eye, giving me the answer I’d come there for in a single word.

“Yes.”