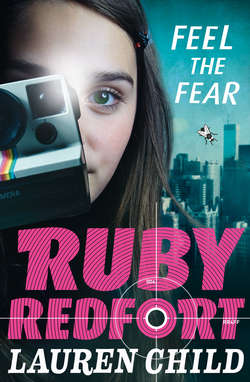

Читать книгу Feel the Fear - Lauren Child - Страница 10

Chapter 1.

ОглавлениеRUBY REDFORT LOOKED DOWN.

She could see the traffic moving like little inching bugs, far, far beneath her feet. She could feel a hot breeze on her face and hear the muffled sounds of car horns and sirens. It was a day like most of the days had been that summer – too hot to be comfortable; the sort of heat that brought irritability and rage and left a sense of general malaise.

Ruby surveyed the whole beautiful picture that was Twinford City – all detail gone from this height, just the matrix of streets and building blocks; huge skyscrapers punctuating the grid. Outside the city, the big beyond: desert to the east, ocean to the west and mountains marching north. From up here on her ledge she could see the giant blinking eye that was the logo of the city eye hospital, with its slogan beneath it: “the window to your soul”.

The eye-hospital sign had been there since 1937 and was something of a landmark. People actually travelled downtown to have their picture taken with the neon eye winking above them.

As Ruby sat there on the ledge of the Sandwich, she was contemplating recent events, and the various ways she had almost met her death – the past couple of months had offered a range of possibilities. Death by wolf, death by gunshot, death by exposure, death by cliff fall, death by fire. In one way it didn’t make for happy reminiscing, but in another it sort of did. She was alive after all, because somehow she had dodged bullets – metaphorical and literal – and was now sitting calmly watching the world go by. It was unlike Ruby to dwell on things, but Mr Death had come so close to knocking at her door that she found herself fascinated by the very thought of it.

Now here she was sitting on the window ledge of a skyscraper, with news of an approaching storm on its way. Some would regard this as a risky activity. Ruby did not. Disappointingly, as far as she was concerned, at this exact moment there were no gusting winds, no adverse weather conditions, not even a stray pigeon looking to take a peck out of her. She judged her spot on Mr Barnaby H. Cleethorp’s windowsill to be no more dangerous than sitting on a park bench in Twinford Square. Well, that wasn’t quite true; there was the danger that Mr Cleethorps would finish his meeting with her father early and they would both give her grief for parking her behind on the ledge of his seventy-second-floor window and playing fast and loose with gravity. But it was hardly the high-octane excitement Ruby had become used to during the past five months as a Spectrum Agent.

Ruby was in the Sandwich Building – or rather sitting on the outside of it – because her father had insisted on bringing her to work with him.

‘Until that cast comes off your arm honey, I’m not letting you out of my sight.’

Her father had become rather over-protective since Ruby’s accident, and he would now only trust her care to his equally jittery wife, Sabina, or the housekeeper, Mrs Digby. A broken arm, an injured foot, singed hair – how close his only child had come to being burnt to a cinder!

Forest fires are very unpredictable, what was she even doing out there on Wolf Paw Mountain? Brant Redfort had asked himself, and indeed anyone and everyone who had walked through the door in the days after the incident.

Brant, as a consequence, was now plagued by fear: he was waking up at four am contemplating the horror of life without his girl. The thought was making him crazy. His fearfulness spread to his wife like a contagious disease and now for the very first time in Ruby’s thirteen years her parents wanted to know exactly where she was and exactly what she was doing at all times. Ruby was going ‘nuts’ as she so delicately put it.

‘Let them worry,’ advised Mrs Digby, a wise old bird who had been with the family since Mrs Redfort was a girl. ‘They’ve never had the sane sense to worry before, it will do them the power of good to employ a little imagination.’

‘Why?’ asked Ruby. ‘What’s the point of them getting all torn up with terror. What benefit is it gonna do them?’

‘They’re too trusting,’ replied Mrs Digby. ‘They don’t see the bad in things like I do.’ Mrs Digby was a big believer in seeing the bad in things – think the worst and you will never be disappointed. It was a motto that had stood her in good stead.

So for now Ruby was doing what her parents wanted; she was biding her time and looking forward to the day when she could lose the arm cast and get her parents off her case.

Ruby’s father was in advertising – the public relations, meet ’n’ greet, shake-you-by-the-hand side of the business. Being friendly to the big important clients was an important job and Brant Redfort was very good at it. Typically, therefore, Brant searched for a tie that might appeal to the client – in this instance, Barnaby Cleethorps, a conservative fellow but a jolly sort. Brant had picked out one that was patterned a little like a red and white chequered tablecloth, scattered with tiny picnic things. Just the ticket, he had winked at himself in the mirror.

As Brant came down for breakfast that morning, he caught sight of his daughter, lounging on the patio table, banana milk in one hand, zombie comic in the other, her T-shirt bearing the words what are you looking at duhbrain?

He sighed. It seemed unlikely that Ruby would be following him into a career in public relations.

‘Now be careful Ruby,’ warned her mother. ‘There are some unsavoury types downtown.’

‘You do know I’m going to Dad’s client’s office, don’tcha?’ said Ruby, sucking down the dregs of her banana milk.

‘Say no more,’ muttered Mrs Digby, who had a notion that the advertising business was rife with unsavoury types.

Brant kissed his wife on the cheek, ‘I’ll keep an eye on her, honey, never fear. What possible harm can come to her in the Barnaby Cleethorps offices?’

Sabina kissed her daughter and hugged her as if a month might pass before seeing her again.

‘Mom, you gotta chill,’ said Ruby, disentangling herself from her mother’s embrace and stepping into the chauffeur-driven, air-conditioned car.

They arrived on 3rd Avenue and took the elevator up to the seventy–second floor. Mr Cleethorps greeted them – ‘nice to meet you young Ruby’ – and he pumped Ruby’s good hand so hard she thought it might come loose from its socket. ‘I see you have been in the wars, but I understand from your father that you’re quite the brave little lady.’

Ruby smiled the smile of a five-year-old, which was obviously what Mr Cleethorps had mistaken her for. ‘How about a drink for our small guest,’ he said. He turned to his assistant, who nodded and smiled and went off to find something suitable – Ruby suspected milk.

As it turned out she was right. She rolled her eyes. Ruby was not a fan of milk, unless flavoured with strawberry, chocolate or her particular favourite, banana.

Once alone Ruby set about finding a good place to dispose of her beverage. There were no plants in the reception area and it didn’t seem good manners to tip it into one of the ornamental glass vases. She scanned the room further and that’s when she noticed that a section of the window in the waiting area could be opened. She stood on a stool, reached up and pulled on the latch. She pushed the window open and a fresh breeze blew in and Ruby couldn’t help wondering how nice it might feel to sit out in that pollution-free air . . .

And that’s how Ruby came to be sitting on the ledge of a very tall building, six hundred feet above street level, wiggling her toes and contemplating the whole big picture. She felt truly calm sitting here on the edge of nowhere. Ruby Redfort had no issue with heights; she’d never suffered vertigo, never felt that strange desire to let herself fall. Fear had never dominated Ruby’s actions, but now fear wasn’t even playing a part. It seemed she had reached a state of fearlessness.

Ruby picked up the glass and flung the milk from it, watching it disperse into tiny droplets that disappeared into the air. She placed the empty glass carefully on the ledge and decided she wouldn’t mind taking a little wander round the building, see her dad schmoozing Barnaby Cleethorps – why not?

The ledge was relatively wide and it was easy to walk to the south corner window and peek into Mr Cleethorp’s office. A slide presentation was obviously in progress, since the slatted blinds were all pulled down, and Ruby could only observe what was going on by peeking through the gaps. A number of the Barnaby Cleethorps team were gathered round looking at designs prepared by the creatives at her father’s agency. There, projected onto the screen, was the slogan the ad agency had spent weeks fine-tuning: “You Have to Feel it To Believe It!”

Ruby could see Mr Barnaby Cleethorps’ face and it was not a happy one. She adjusted her position on the ledge so she could see her father’s expression. As always, he looked remarkably cool, not in any way flustered, but she knew he must be feeling the strain because he was heading towards the window, and when her father was feeling tense his response was usually to let in some air. Tension brought on a sort of claustrophobia – too much stress in one room made it difficult for him to breathe.

Ruby ducked down, making herself as small as she could. Not that Brant could have seen her through the Venetian blind, but she didn’t want to take any chances.

The opening of the seventy-second-floor window might have helped Brant Redfort regain his calm, but for his daughter it had entirely the opposite effect. The problem was that Ruby had not anticipated how the window might open; she was expecting it to hinge in the middle when in fact this huge window was of the pivoting variety, and as her father yanked it open Ruby was flung out into thin air. She landed in – or, more accurately, dangled from – one of those window-cleaning cradles that travels the length and breadth of skyscrapers, allowing maintenance guys to squeegee the acres of glass. Luckily there were no maintenance guys in it now, though unluckily it meant there was no one to pull Ruby back in.

Now, suspended six hundred feet above the downtown traffic which crawled and tooted beneath her, she could see the irony of the situation – her father, intent on keeping her safe, had almost brought about her demise.

But at this precise moment she was struggling to see the funny side.