Читать книгу Trace - Lauret Savoy - Страница 11

ОглавлениеOne journey seeded all that followed.

We had entered Grand Canyon National Park before sunrise, turning west onto the primitive road toward Point Sublime. This was in those ancient days when a Coupe de Ville could negotiate the unpaved miles with just a few dents and scrapes. My father had driven through the Kaibab Plateau’s forest on Arizona Highway 67 from Jacob Lake, Momma up front with him. No other headlights cut the dark. I sat in the backseat with Cissie, my dozing eighteen-year-old cousin. Our Kodak Instamatic ready in my hands, cocked. For two hours or more we passed through shadows that in dawn’s cool arrival became aspen-edged meadows and stands of ponderosa pine. Up resistant limestone knolls, down around sinks and ravines. Up then down. Up then down. In time, through small breaks between trees, we could glimpse a distant level horizon sharpen in the glow of first light.

Decades have passed, nearly my entire life, since a seven-year-old stood with her family at a remote point on the North Rim. I hadn’t known what to expect at road’s end. The memory of what we found shapes me still.

POINT SUBLIME TIPS a long promontory that juts southward into the widest part of the canyon, a finger pointing from the forested Kaibab knuckle. It was named by Clarence Edward Dutton with other members of field parties he led between 1875 and 1880, first on John Wesley Powell’s Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, then under the new U.S. Geological Survey. To Dutton the view from the point was “the most sublime and awe-inspiring spectacle in the world.”

The year the Grand Canyon became a national park, in 1919, more than forty-four thousand people visited. Most of them arrived by train to the South Rim. On the higher and more remote North Rim, those daring could try wagon tracks used by ranchers and “pioneer tourism entrepreneurs” over rough limestone terrain to Cape Royal and Point Sublime. Or they could follow a forest service route to Bright Angel Point. Soon roads scratched out on the Kaibab Plateau would replace the old wagon paths, allowing work crews to fight fires as well as infesting insects.

But the summer of 1925 would be a turning point. For the first time, and ever since, visiting motorists outnumbered rail passengers. The National Park Service encouraged and responded to this new form of tourism by building scenic drives and campgrounds on both rims. Auto-tourists often attempted the twisting, crude road to Point Sublime.

The Grand Canyon now draws nearly five million visitors each year. The seventeen-mile route to Point Sublime remains primitive, and sane drivers tend not to risk low-clearance, two-wheel-drive vehicles on it. Sometimes the road is impassable. One year it was reported to have “swallowed” a road grader. Still, the slow, bumpy way draws those who wish to see the canyon far from crowds and pavement, as my father wanted us to do those many years ago.

None of us had visited the canyon before that morning. We weren’t prepared. Neither were the men from Spain who, more than four hundred years earlier, ventured to the South Rim as part of an entrada in search of rumored gold. In 1540 García López de Cárdenas commanded a party of Coronado’s soldiers who sought a great and possibly navigable river they were told lay west and north of Hopi villages. Led by Native guides, these first Europeans to march up to the gorge’s edge and stare into its depths couldn’t imagine or measure its scale. Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera chronicled the expedition:

They spent three days on this bank looking for a passage down to the river, which looked from above as if the water was six feet across, although the Indians said it was half a league wide. It was impossible to descend, for after these three days Captain Melgosa and one Juan Galeras and another companion, who were the three lightest and most agile men, made an attempt to go down at the least difficult place. . . . They returned about four o’clock in the afternoon, not having succeeded in reaching the bottom on account of the great difficulties which they found, because what seemed to be easy from above was not so, but instead very hard and difficult. They said that they had been down about a third of the way and that the river seemed very large from the place which they reached, and that from what they saw they thought the Indians had given the width correctly. Those who stayed above had estimated that some huge rocks on the sides of cliffs seemed to be about as tall as a man, but those who went down swore that when they reached these rocks they were bigger than the great tower of Seville.

The Spaniards knew lands of different proportions.

Writing more than three centuries later, Clarence Dutton understood how easily one could be tricked by first views from the rim. “As we contemplate these objects we find it quite impossible to realize their magnitude,” he wrote. “Not only are we deceived, but we are conscious that we are deceived, and yet we cannot conquer the deception.” “Dimensions,” he added, “mean nothing to the senses, and all that we are conscious of in this respect is a troubled sense of immensity.”

Point Sublime holds a prominent place in Dutton’s Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, the first monograph published by a fledgling U.S. Geological Survey in 1882. Lavishly illustrated with topographic line drawings and panoramas by William Henry Holmes, Thomas Moran’s paintings and drawings, and heliotypes of Jack Hillers’s photographs, it is an evocative work from a time when specialized science hadn’t yet constrained language or image. The monograph also shows a science coming of age. For in the plateau and canyon country, aridity conspired with erosion to expose Earth’s anatomy. The land’s composition and structure lay bare. Though terrain was rugged and vast, equipment crude or lacking, these reconnaissances tried to sketch plausible models for land-shaping forces. Clarence Dutton gazed out from the North Rim at Point Sublime to describe the grand geologic ensemble: the great exposed slice of deep time in canyon walls, the work of uplift and erosion in creating the canyon itself. Dutton also brought his readers to the abyss’s edge to see with new eyes.

The men on the surveys by and large beheld with eastern eyes, responding at first with senses accustomed to the vegetative clothing of a more subdued, humid land. They saw at a time when various meanings of “the sublime” had become essential to how the educated in Europe and their descendants in America conceived of the world about them. In a Romantic sublime one encountered power greater than imagined or imaginable. One beheld the might and presence of the Divine. On a mountain peak. In a great churning storm. At the brink of a fathomless chasm. To come to the edge of the Grand Canyon and experience the sublime was to feel unsettled, deeply disoriented. To be awestruck. “In all the vast space beneath and around us there is very little upon which the mind can linger restfully,” Dutton wrote. “It is completely filled with objects of gigantic size and amazing form, and as the mind wanders over them it is hopelessly bewildered and lost.”

But he didn’t stop there. Dutton realized that objects disclosing “their full power, meaning, and beauty as soon as they are presented to the mind have very little of those qualities to disclose.” After many field seasons he came to see the “Grand Cañon of the Colorado” as “a great innovation in modern ideas of scenery, and in our conceptions of the grandeur, beauty, and power of nature.” Such an innovation couldn’t be comprehended immediately. “It must be dwelt upon and studied, and the study must comprise the slow acquisition of the meaning and spirit” of the country.

The lover of nature, whose perceptions have been trained in the Alps, in Italy, Germany, or New England, in the Appalachians or Cordilleras, in Scotland or Colorado, would enter this strange region with a shock, and dwell there for a time with a sense of oppression, and perhaps with horror. . . . The tones and shades, modest and tender, subdued yet rich, in which his fancy had always taken special delight, would be the ones which are conspicuously absent. But time would bring a gradual change. . . . Great innovations, whether in art or literature, in science or in nature, seldom take the world by storm. They must be understood before they can be estimated, and they must be cultivated before they can be understood.

The author Wallace Stegner wrote his dissertation on Clarence Dutton, later referring to him as “almost as much the genius loci of the Grand Canyon as Muir is of Yosemite.” Tourists visiting the park might not be aware of the debt owed, but Stegner believed “it is with Dutton’s eyes, as often as not, that they see.” While residents of eastern landscapes might have spurned canyons and deserts as irredeemably barren, Dutton’s words and vision helped change the terms of perception. That is, for an audience acquainted with particular notions of the sublime and nature, an audience with the means, time, and inclination to tour.

• • •

What did my family bring to the edge and how did we see on that long-ago morning? I’ve wondered if the sublime can lie in both the dizzying encounter with such immensity and the reflective meaning drawn from it. Immanuel Kant’s sublime resided in the “power in us” that such an experience prompted to recognize a separateness from nature, a distance. To regard in the human mind an innate superiority over a natural world whose “might” could threaten flesh and bones but had no “dominion” over the humanity in the person. In Kant’s view, neither I nor my dark ancestors could ever reach the sublime, so debased were our origins. In Kant’s view neither could W. E. B. Du Bois, for whom this “sudden void in the bosom of the earth,” which he visited half a century before us, would “live eternal in [his] soul.”

We had little forewarning of where the Kaibab Plateau ended and limestone cliffs fell oh so far away to inconceivable depth and distance. The suddenness stunned. No single camera frame could contain the expanse or play of light. Canyon walls that moments earlier descended into undefined darkness then glowed in great blocky detail. As shadows receded a thin sliver in the far inner gorge caught the rising sun, glinting—the Colorado River.

I’ll never know what that morning meant to my father when he took this detour on his homeward journey. Or to my mother. We traveled together but arrived with different beholding eyes.

This was The Move. My parents were returning to a familiar and familial East. My home lay behind us on the sunset coast, where I was born at the elastic limit of my father’s last attempt to craft a life far from Washington, D.C. Movement and change had occurred often—from San Francisco to Los Angeles, from rented bungalow to apartment to second-story flat. The last to 1253 Redondo Boulevard. But these were small steps, our lives pacing an unchanged rhythm. Momma worked as a surgical nurse, mostly night shifts. Dad did many things—marketing, public relations, jobs I never really knew. We lived by what I now know were modest means, each home furnished with what was necessary, accented by his ceramics, pastels, paintings, handmade table and lamp.

In a neighborhood with few children, my reliable companions were sky’s brilliant depth and the tactile land. The Santa Monica and San Gabriel Mountains shaped the constant skyline north and west.

If a child’s character and perceptual habits form by the age of five or six, then I perceived by sharp light and shadows. If a child bonds with places explored at this tender age, and those bonds anchor her, then I chose textures and tones of dryness over humidity, expanses that embraced distance over both skyscraper and temperate forests.

So when my father, nearing fifty years of age, decided to return to Washington, D.C. to try again, I told my parents to leave me behind. We had visited his family there; I wanted no more of it.

But a seven-year-old has little choice short of running away. If I could gather sunlight and stones, if I could keep Pacific Ocean water from spilling or drying up, then home could come with me.

Sifting through memory’s remains—of words spoken, decisions made, actions taken—feels like the work of imagination in hindsight. The scaffolding that ordered my world stood on happenstance. That because my father decided we’d drive across country in a leased Cadillac, roomy and comfortable enough for four; because he chose to stop at national parks on the way—because of these things I stood at that edge, a small child with a Kodak Instamatic in hand.

Those moments at Point Sublime illuminated a journey of and to perception, another way of measuring a world I was part of yet leaving behind. I felt no “troubled sense of immensity” but wonder—at the dance of light on rock, at ravens and white-throated swifts untethered from Earth, at a serenity unbroken.

The ocean I’d tried to bring across country had evaporated. Sunlight wouldn’t be contained. But pebbles came willingly. Limestone joined basalt, sandstone, and granite on the rear window mat. Images of the canyon, Kaibab Plateau forest, and Colorado River thickened the growing stack of postcards.

EROSIVE FORCES CARVED the North Rim’s edge. My family crossed many edges that summer. West to East. One childhood home left for another. Before to after. History began for me on The Move. What preceded was a sense of infinite promise and possibility in a world that made sense. What followed promised nothing. Daddy hoped the nearing future would be a return to origins and dignity. My soon constant question to him, “When are we going home?” always met the same response: “We are home.”

My bearings lay in memories of bright days, in snapshots and postcards, stones and a salt-encrusted jar. By the age of ten I knew it was better not to want anything too badly.

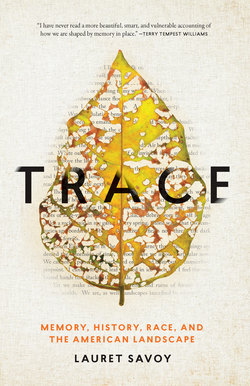

I’ve tried to return to Point Sublime many times. Fire danger and an impassable road aborted all but two attempts. The wooden post still stands, but without the carved sign that marked our presence in a photograph from that distant morning. POINT SUBLIME ELEVATION 7464. Three of us face morning light; our shadows stretch toward the edge, oblique dark columns. Dad leans against the sign, his mouth caught in midsentence. Cissie stands next to him, her Uncle Chip. In front of them, in pressed pants and first-grade uniform blouse and sweater, a child looks down and away. She waits for the shutter to click.

Good morning, yesterday. Gazing into this image, I see us as my mother did—then beyond, toward the abyss. I know our future.

Now my father’s age then, I am a witness from a later time checking the rearview mirror. Most of my life has taken place in the East for reasons that at moments of decision seemed right. It’s impossible to step into that bright summer morning again, attentive to it, to parents alive, to an intact family drawn by hope and promise. Point Sublime remains. I still try to negotiate its terrain.