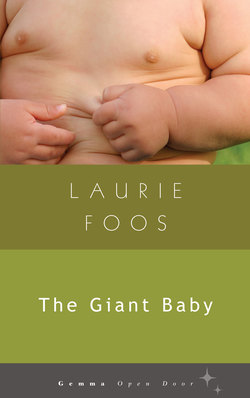

Читать книгу The Giant Baby - Laurie Foos - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTWO

It all started with the toes.

But I should explain. I have some explaining to do, just like Ricky used to say to Lucy on the old I Love Lucy show when Lucy got busted (always) for trying to find herself a part in one of Ricky's cabaret shows where he sang the “Babalu.” That Lucy, always getting caught with fruit piled on her head or grapes between her toes, trying to wind her way onstage with Ricky. And he caught her every time, and would say in that accent of his that she had some “'splaining to do.” But I didn't understand what there was to explain. Why didn't Ricky get it? All Lucy ever wanted was more time with Ricky.

Earl and I were like Lucy and Ricky in that way, I guess. We were always trying to be together more, or more together somehow. I'd fallen in love with Earl the minute I'd heard his name.

“The name's Earl,” he said to me that day at the vegetable stand, when he reached for a carton of cherry tomatoes at the same second I did. I looked down at his hand on top of mine, our two hands both covering the redness of the cherry tomatoes, and I blushed in a way I hadn't blushed for years.

“Earl,” I said. “Earl.”

I repeated the name to him as if I weren't sure I'd heard him right. I remember letting the name rest in my mouth as if I were tasting it. You don't meet many men named Earl anymore. I'd always wanted to meet a man named Earl, though I hadn't known it until the second he'd introduced himself. Earl, I thought, such a solid name. The kind of name you could count on. What had happened to all the solid names of the past? Short bursts of men's names like Chuck or Ed or Burt. Or Earl.

I said to myself as I took the little basket of cherry tomatoes he handed to me, I'm going to fall in love with a man named Earl and grow a whole life with him someday.

And that's just how it happened. We left that vegetable stand and have been together ever since. Even when Earl had to be away from me to work at the lumber yard, I could still feel him inside of me. I thought of that feeling as the “Essence of Earl,” and it was that feeling that we brought to the house we built and to the garden we grew together. Sometimes I thought that if I could open Earl up and climb my way inside of him and stay in there, in the innards of Earl, I would. At night when we slept, I'd curl up next to Earl and press my face into his back and whisper to myself, Oh, sweet Essence of Earl, let me get inside.

And Earl would press his back harder against me, as if he could feel it, too, and wanted me in there, the two of us folded over each other, skin over skin and bone to bone, muscle and heart and blood that pumped.

But that was before everything happened, when we were just Earl and Linda and no one else.

Earl had gone to the garden that day without me, the way he sometimes would after he was fired from the lumberyard. Poor Earl had sold the wrong kind of wood to a couple who built a deck that collapsed after a party. A highly intoxicated and obese man had done a cannonball into the pool that the deck surrounded. There had been a lawsuit. The man—whom the lawyers always called obese instead of huge or fat and intoxicated instead of drunk—had splinters in places that splinters are never meant to prick through, Earl reported to me on the day he was let go.

“The boss just looked at me and said, ‘Damn it, Earl, if you don't know the difference between cedar and untreated pine by now, may God save your sorry soul,’” Earl said as we stood at the window that overlooked the backyard. We stared out at the broken pumpkin tree.

I told him that, to my mind, no obese drunken man should attempt a cannonball without thinking of the consequences beforehand.

“Splinters or no splinters, that's just downright irresponsible,” I said, and Earl pulled me closer and pressed his nose into my hair.

“Oh, Linda,” he said, “if only the whole world could see things the way you do. But I've got no business selling wood anyway, when all I want is to be out with you in the garden.”

We had pumpkin soup in bread bowls that night for dinner, and a few weeks later Earl found the toes while I lay on the Barcalounger reading the seed catalogue. We hadn't planted anything new in a while, and, for a time, we'd cut our losses. We'd taken the soil to the nearby garden center and had the soil tested. “Ph perfect,” they pronounced it, with nothing showing too much acid or fungus or whatever it is they look for when they test people's soil. Sometimes I wonder what makes a person decide to go into the business of soil testing, but then I think: who am I to judge? I grew a baby in my backyard.

I have no room to talk.

I had my tea on the end table next to me and my knees curled up under the coverlet. I was reading about flowers, thinking that maybe if Earl and I planted flowers rather than fruits or vegetables we would have a change of luck. I imagined roses the size of lanterns, Earl and I trimming and weeding and tending the way we'd imagined we would when we'd started the garden years ago. I closed my eyes and imagined Earl and me standing barefoot in the soil, the smell of roses so strong we had to cover our mouths to drown it out. I could almost feel the dirt under my feet as I lay back in the lounger. The seed catalog fell to the floor as I closed my eyes and thought of roses that would wind their way around my arms and my legs, up through my hair, the vines and thorns twisting my hair into braids.

When I opened my eyes, there was Earl with this look on his face. It was a look I'd never seen before, not even after the accident with the backhoe that had sealed our childlessness forever.

“For God's sake, Earl,” I said, “you didn't hurt yourself, did you?”

I was worried about Earl. He hadn't been the same since the firing, or, before that, since the backhoe ruined him in ways a man shouldn't be ruined. it wasn't something we talked about, the day he'd gotten himself run over by the backhoe, but the memory of it lingered. it did. We hadn't wanted babies all that much, and I was older now, too old. One day a woman from town stopped me at the grocery store and told me that she hadn't seen me looking this thin before, and was I dieting or working out.

“Working out?” I asked, and she said, “Yes, Linda, you know, with weights and all.” When I said that I hadn't been, unless you counted being out in the garden on my hands and knees, she said no, gardening never made anyone look so lean.

“Oh, that's it then,” she'd said, “you're just getting old.”

I was thinking about that neighbor woman and the day Earl had been bloodied by the backhoe, the stitches and the ice packs, when Earl sat down on the edge of the Barcalounger and told me to close my eyes.

“Promise me, Linda,” he said, his voice low as he leaned closer to me, his hands clasped one on top of the other. “Promise me you won't open them until I say.”

I pressed my hands into my thin arms and felt the muscles and bones sticking out of me, the veins, too, and thought that the neighbor woman was right. I was getting old.

“Earl, what is it?” I said. “You're scaring me now.”

He kept his hands squeezed tightly together and smiled with one side of his mouth slightly higher than the other, his best Earl smile, the one he gave only to me. To hell with that woman, I thought. I might have been getting old, but I still had this.

“Close your eyes now, just like I said,” he told me, and as I closed my eyes I could hear the breath in his chest moving in and out, little hisses that had helped me sleep for all these years.

“Don't look,” he said. “Don't look until I say.”

I closed my eyes and kept them closed. I kept my promise to Earl and did not open them again until he told me to. I don't know what I was expecting to see but when I opened my eyes, I knew that I hadn't been prepared for what I was about to see.

He told me to open my eyes, and when I did, he parted his hands and sat there cradling the things he had brought in from the garden.

Toes. Baby's toes. Ten of them, and not just bones, but pink skin and impossibly tiny nails.

I looked up at Earl, and he looked back at me. I cupped my hands as he poured the toes into my palms.

“Are these what I think they are?” I whispered, and Earl nodded, folding one hand over the two of mine.

“From the garden,” he said.

I stared down at those perfectly formed miniature toes and felt them grow warm in my hands. Slowly I counted them over and over, one through ten, marveling at the shape of each toe, the plumpness of the big toes, the splendor of the pinkies.

“Our luck is about to change,” he said, and I didn't answer him. I kept holding the toes and wondering what was going to happen to us now that the garden that we thought had turned against us had now risen up and sent us ten baby's toes.