Читать книгу Westover - Laurie Lisle - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

My Westover

THIS BOOK HAD ITS BEGINNING IN THE AUTUMN OF 1971, WHEN I was working for Newsweek in New York. In the wake of the women’s liberation movement, I was seeing everything with new eyes, and I wanted to re-evaluate my life as a girl, especially my three years at Westover. The impact of leaving home at the age of fifteen for a hermetic female community had been huge. As far as I could tell, the school had changed very little from the time my mother had attended in the late 1920s and early 1930s. I wondered why I had never heard the words “women’s rights” spoken by my intelligent and independent women teachers, even by the indomitable Louise Dillingham, who had ruled the place for many years with a peculiar combination of absolute authority and enigmatic detachment. I was wondering about other matters, as well.

After graduating in 1961, my memories of my years in Middlebury, Connecticut, remained unresolved. They were as charged as if radioactive, and as ongoing as a persistent itch. I remembered my restlessness because I didn’t believe I was being readied for Real Life. Although I realized I was getting an excellent education, I also wanted something else. After graduation, my adolescent ambivalence turned to antagonism, when alumnae news was more about weddings than professional work or other kinds of adventures. As boys’ prep schools went coeducational, I applauded, regarding female institutions as anachronisms, something I had endured simply because I was born too soon.

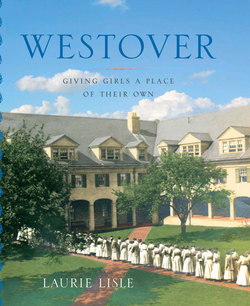

Intending to write a freelance article about girls’ schools from my new point of view, I wrote to Westover’s acting headmaster for an interview. I was more comfortable returning as a reporter than an alumna and had skipped my tenth reunion the previous spring. When I drove up to the school’s imposing façade along the side of a village green, all the nervousness and anticipation I had felt when returning from vacations came rushing back. I pushed open the heavy front door, walked in, and there was Red Hall flooded with sunlight, with the green grass and little apple trees within the Quad visible through its large windows. Standing in that familiar, feminine place, I felt enveloped by emotion. To my astonishment, I felt a sense of solace. I tried to resist this feeling because it undermined my new ideas. An enthusiastic supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment, I espoused equality and togetherness with males, and I rejected the ideas of womanly retreat and feminist separation.

Why did it feel so, well, pleasant to be back?

Perhaps it had to do with tricks of memory or the beauty of the place. Still, my reaction didn’t make sense to me. After all, I had suffered adolescent angst while there. Maybe I was tired of gender battles in Manhattan, where my boyfriend seemed to live in the Dark Ages, and where female editorial employees of Newsweek had filed a complaint with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission protesting the magazine’s discriminatory policies against them.

In the interview, soft-spoken Joseph Molder gave me the impression that he was “more on the girls’ side” than I had expected, my notes of the meeting say. My notes also reveal my point-of-view at the time: It would be a mistake for alumnae to make the school “a bulwark against change in their daughters and granddaughters, rather than a good opportunity to mold the new woman creatively.” Afterward, he introduced me to a long-haired, bearded English teacher about my age, who startled me by saying he was getting girls to read women writers like Sylvia Plath. I was also surprised to see students in their own clothes, to hear about their baking cookies at the headmaster’s house, and to see them riding off on bikes to volunteer jobs outside the high walls of the school. In a note to Mr. Molder after I returned to New York, I thanked him for answering my questions so “patiently and graciously” and praised his “sensitive touch” as headmaster. Then I asked him if the school was ever going to teach sex education or women’s studies. (I never got an answer to that question.)

Then I got in touch with the president of the board of trustees, who politely invited me to lunch at his Wall Street club, a hushed place with red walls and large models of sailing ships. As we talked, he indicated that Westover’s future was up in the air, and that it might become a school for remedial students. Noticing that I was almost the only female in the room, I asked if we were in a men’s club. When he nodded yes, I felt a stab of resentment. Maybe my conflict had less to do with my dislike of the female sphere than my perception of its inferiority to the male one, where the prizes, I thought, were the ones worth winning. Since I had intended my article to be critical of girls’ schools, I was confused. I had no idea how to begin it and, in fact, I never did.

Years later, after returning from my thirty-fifth Westover reunion in 1996, I read in The New York Times about the opening of the Young Women’s Leadership School, the first public school for girls to open in the city in a century. I instantly understood what the young girls in East Harlem would get from a school of their own, and I felt happy for them. I also realized that I was glad that Westover was still a school for girls, and that it had been mine for a while. Even at the time of the interview I had noted that “I guess the place either gave me or nourished my desire to dream and grow.” Entering at the end of the 1950s, I must have absorbed the message that girls like me were important because such a magnificent piece of architecture had been designed for us and dedicated to educating us. Also, I remembered being interested in the school motto, “To Think, To Do, To Be” (inscribed in Latin on our brass belt buckles and the awesome emblem over the front door). It boldly challenged the expectation for a girl’s life in an era when women were only assumed to exist, instead of also thinking and doing. The words must have interested me because they assumed no inherent conflict between intellectuality and femininity: they indicated that clear thoughts and bold actions were part of a womanly life.

Soon afterward I returned to Middlebury to examine the school archive on the balcony of the former library, the airy, white clapboard colonial that had once been a church. I loved being back in the beautiful old building, and I remembered being happy reading on its sofa in the warmth of the fireplace on winter afternoons. The large portrait of founder Mary Robbins Hillard still hung there, the doe-eyed likeness that makes her look smaller and sadder than the way my mother remembered her. Maybe I would find material for the article left unwritten so long ago or for a book about girls’ schools. The archive was indeed full of treasures—letters, diaries, manuscripts, photographs, memorandums, minutes of meetings, and many other materials carefully collected over the years by alumna archivist Maria Randall Allen. Eventually, when she suggested that I write a history of Westover, I realized it was what I really wanted to do—to examine the place that still evoked such strong emotion.

One day while perusing the large, gold-embossed, old leather-bound school guest book, I saw what looked like the signature of my grandfather. He and my grandmother may have visited in May of 1923, when my mother and her older sister were still in grade school. It was my grandmother who must have heard about Westover from an older cousin in Massachusetts, whose daughter, Eleanor, had entered when it first opened in 1909. I will never know how the Coles heard about Miss Hillard’s new school in Connecticut, but it doesn’t matter. In Eleanor’s old age—eighty years after her graduation in 1912—she remembered that she had “worshipped” her headmistress and “adored” her years in Middlebury. She had not been especially studious, she said, but she had loved all the singing and the “feeling of freshness and, in a way, hope” in the “lovely little chapel,” whose beloved chaplain had officiated at her wedding.

My mother was in her eighties when I began working on this book, and I enjoyed entertaining her with what I was discovering in the archive. I liked taking her to visit her sister-in-law, a member of Westover’s class of 1930, and one afternoon my stories inspired the two old ladies to break into a spirited “Raise Now to Westover.” After my mother’s death, when I was going through her attic, I found her khaki day and white evening school uniforms, carefully tucked into a trunk along with a wedding dress. I held up the uniforms and marveled at their exquisite tailoring: all little tucks, intricate seams, deep hems, and lovely embroidery. Then, most miraculously of all, I discovered in the attic many girlish letters, written in achingly familiar handwriting, that she had mailed to her parents from Middlebury.

My mother had wanted me to go to Westover, too. In fact, she never even suggested the possibility of my going away to any other school. It was go to Westover or stay home—despite the fact that her memories were a mixture of pleasure and shame. While at boarding school, she had learned a love of reading, made good friends, and been elected head of the Over field hockey team, but she had left without a diploma. She did not attend her class’s graduation or ever return for a reunion, as far as I know. Still, she felt that Westover was an experience her daughters should not miss.

During my childhood, she had often talked about a larger-than-life personage, a Miss Hillard, a kind of Protestant princess or priestess in my imagination, who could read girls’ minds. Mother never spoke about her own mother with the same kind of awe. She also made affectionate references to a young headmistress, whom she called “Dilly,” who sounded like the nicest person in the world. My mother often recited poems to me that she had memorized during her four years away at school, like Emily Dickinson’s paean to reading, a little, rhyming poem called “A Book.” She also used to recite a Biblical passage that she knew by heart, and that I would also learn at Westover—“Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not Love, I am become as sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal,” it begins. I still have my tiny blue booklet about it given to me and everyone in my class by Miss Dillingham in 1959, full of my scribbled, idealistic reflections.

On an autumn day when I was fourteen, my mother drove me to Middlebury to meet “Dilly” and see the school I had heard so much about. I remember a long talk with a formal and formidable Miss Dillingham in her dimly lit sitting room, when my mother nervously did most of the talking. At home in Providence, I had taken to bickering with her, and I didn’t get along with my stern stepfather, either. “Growing up was growing out, I had nothing to lose, so I was ready to go,” I had remembered a decade after graduating. When the acceptance letter arrived a few months later, I was glad to be going.

Walking through Westover’s front door in September of 1958, I was a quiet girl, distressed, maybe even depressed, by feeling voiceless at home. In the presence of my volatile stepfather, it was impossible to say much of anything. Before long, after discovering the daily pile of The New York Times on a high-backed bench, I became electrified by news about the nascent civil rights movement. I tentatively started to talk about it, and soon I was offering my opinions in Current Events and Miss Norman’s history class, on the volleyball court and everywhere else. Rooting for the Overs seemed less important than defending the pacifism of Martin Luther King. My classmates gently teased me for my passionate and probably dogmatic views, but they, as well as my teachers, put up with my argumentativeness.

My newfound voice was not just verbal, either. I began keeping a diary, writing about my thoughts as well as my emotional ups and downs. After returning from a “perfect” Christmas vacation during junior year, it suggests that I had a mid-winter meltdown. I was seventeen, in my seventh year in a girls’ school (including a day school in Providence), and eager to experience life. I was also starved for difference, but most of my classmates were, like me, daughters of alumnae from established Protestant families. Everything suddenly seemed too female, too boring, and too tense. I telephoned my mother in tears, telling her that I wanted to go to another school senior year, definitely one with boys. She sighed and suggested that I go talk to Miss Dillingham. At the age of sixty-two—incredibly, younger than my age now—the headmistress appeared to me as a powerful but benevolent grandmother figure, not unlike my own widowed grandmother. The next day I fearlessly went to see the person we called Miss D in her sitting room. Our talk elated me, evidently because of her empathy. “It came down to the point that maybe I was ready to go on and that enough of boarding school is enough,” I told my diary. “I’ve just outgrown this place.” Wisely, she asked me to wait until after spring vacation to make a final decision, and I willingly agreed.

It wasn’t long before I went to see her again, this time to ask if I could take a rare weekend pass to go to Harlem for a seminar for teenagers at a Quaker settlement house. She said she would think about it and, after undoubtedly calling my mother, gave permission. Despite being “petrified,” my diary says, I was soon on a train to New York, where I was met by two boys wearing American Friends Service Committee tags and taken by subway to a narrow brownstone on East 105th Street and another kind of life.

That evening or the next, a square dance was organized for those of us from elsewhere and the Puerto Rican teenagers in the neighborhood. Smoking incessantly, the young men, who wore black felt hats pulled down over their foreheads and long hair, seemed older and more guarded than others my age. As an accordion player warmed up, a dance set was formed, and our two groups eyed each other nervously. I smiled uncertainly at the girl with jangling earrings and elaborately curled hair opposite me, and she quickly beamed back. The dancing started awkwardly—they had never square danced before—and it ended in twirling circles that made all of us dizzily collide and collapse on the floor. After a moment of silence, a titter broke out, and soon everyone was laughing together.

Back in Middlebury, I landed in the infirmary with a sore throat after four days of sleeping little and eating erratically. In the silent, snowy, wintry beauty around me, I reflected on the overcrowded tenements, overflowing garbage cans, and noisy streets of East Harlem. I had been shocked by its ugliness, but not as much as by a despairing parody of the Twenty-Third Psalm, which a young addict had slipped into my hand. “Heroin is my Shepherd: I shall always want. It maketh me to lie down in gutters,” it began, and it ended: “Surely hate and evil shall follow me all the days of my life, And I will dwell in the house of misery and disgrace forever.” When I recovered, returned to the dormitory, and dressed in my white eyelet evening uniform for dinner, an elderly housemother reprimanded me for wearing seamless stockings, presumably because they made me look bare-legged. After my days in Harlem, I was infuriated by her pettiness. It was 1960, however, and it did not enter my mind to rebel against the rules. My plan was to go to another school.

That year I was taking a creative writing elective. It meant so much to me that I have saved my notebook from the class, as well as the classic grammar we were given, The Elements of Style, by E. B. White and William Strunk, Jr. The first page of the notebook has a quotation by Joseph Conrad about the purpose of writing, undoubtedly dictated by our teacher, white-haired and soft-spoken Miss Kellogg, English department chair and Bryn Mawr alumna, whom Miss Hillard had hired in 1925. On the second page, I dutifully wrote down more time-honored rules about writing, and then, as in any working writer’s notebook, I used the rest of the ruled pages for essay and story ideas as well as bits of dialogue and description. I have never forgotten the excitement of a homework assignment from that class: taking a topic from a basket in the schoolroom, and then writing about it for half an hour. I must have loved that exercise in extemporaneous writing because it was an invitation to voice.

As I wrote, the act of writing enabled me to sublimate my desires and summon the patience to postpone what I imagined was really living. A few weeks after returning from New York, but well before spring vacation, I announced to my diary, “I’m staying. What’s one year out of a lifetime?” I found a roommate and applied for a summer program with the Quakers. And I wrote. The extreme contrast between Harlem and Middlebury called for comprehension, and it fueled my words. It was then when I intuited that I had the mind set of a writer, and the inclination to be more of an observer than a participant. The pleasure of expressing myself on paper was enhanced the following June, when one of my essays about Harlem was published under my byline in the school literary magazine, The Lantern.

Senior year was surprisingly happy. In October, I loved thinking hard in the mornings and playing tennis vigorously in the afternoons. As always, I found my classes intellectually exciting, or mentally “invigorating,” as I put it in my diary, and I was doing well in all of them except for French. I also noted that “being away from the world gives you a chance to think about things.” Since everyone’s femaleness was taken for granted, it was downplayed, and we were free to dream outside the narrow gender expectations of the era. In November, I was thrilled when President Kennedy was elected, and I planned to join his Peace Corps. And, despite my Unitarian reservations about the Anglican liturgy, I liked what I called the “peace and beauty” of the lovely little chapel with its large arched window, especially at Christmastime, when it was full of sweet-smelling greenery. That winter I contentedly worked on a paper for Miss Dillingham’s senior ethics seminar about nonviolence in the civil rights movement. When the pond froze, the ice hockey was exhilarating. In Introduction to Philosophy, Mr. Schumacher asked us to write about what we wanted in life, and, at a time when few women I knew had careers, I wrote in turquoise ink that I wanted two of them: to be a writer and a social worker. That school year had its disappointments, too. After getting permission from Miss Dillingham to drop mathematics after sophomore year, I was disappointed when I did poorly on my math SAT. She told me it didn’t matter, since I was going to major in history or political science. But I was right to be worried, and I did not get into the college of my choice.

At Ohio Wesleyan, I stayed away from sororities after so many years at girls’ schools. But after being mocked in a mostly male history class when speaking up, I gravitated to literature classes with more female students and became an English major. If women did not make history, I told myself, they had at least written novels for centuries. Literature was as close to a female sensibility as I could find in academia at that time before women’s studies courses. After graduating, I went to work for a daily newspaper in Providence before moving to New York. It was a struggle to write on my own, until I left Newsweek after six years to write a book. After it was published, I moved from Manhattan, eventually settling into a small historic house (called “the Academy,” since part of it had once been a schoolhouse) on a village green in northwestern Connecticut. Without really realizing it, I had found a place like Middlebury, where I developed a pattern of writing in the mornings and walking or gardening or researching or running errands in the afternoons, not unlike the rich rhythm of life I had learned so long ago at Westover.

Working in the archive on this book, I was alternately surprised, amused, saddened, and almost always interested in what I was finding. I interviewed alumnae, administrators, trustees, and teachers, including my former English teacher, Miss Newton, who amazed me by saying she not only remembered me but also recalled my total absorption and involvement in classroom discussions. This demanding teacher had wanted me to think harder in her Nineteenth Century Literature class, so I was glad to give her a copy of my first book and get a nice note from her about it. I decided that she and my other teachers had not used feminist language in the 1950s because it was risky and, besides, many of them were living the lives of liberated women anyway. Being in Middlebury and returning to my own and others’ reunions, I got to know the school again. It was gratifying to see the way it had transformed itself through the decades into a place that is better than before—more informal, more open, and much more diverse—while still offering excellence in the classroom. While Miss Dillingham had endorsed a kind of tough love, I learned that Ann Pollina has brought great warmth to Westover, and it is what she calls “a place with heart.” As always, students get used to expressing themselves and being smart and strong. It is without question a good place for girls.

Reading letters and diaries of other alumnae and listening to their stories, I understand that we shared much, but that we experienced it differently. Sometimes it seems as if we went to different schools. My Westover is unlike anyone else’s, yet, like everyone else, I feel a sense of possessiveness about it. Inevitably, this history of our school is about what I read and remembered as well as what others revealed to me and reminded me about. And, as I learned about our school’s past, I learned more about myself. At times I was sorry for that struggling teenager, but I was glad to discover in my student file that Miss Dillingham had had a better opinion of me than I had of myself. Looking back, I’m grateful that my Real Life was delayed for a few years so that I could imagine the life I really wanted to live.

L. L.

Sharon, Connecticut