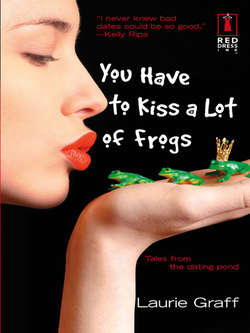

Читать книгу You Have To Kiss a Lot of Frogs - Laurie Graff, Laurie Graff - Страница 9

4 David's Dad

ОглавлениеRosh Hashana

Central Park West, NYC 1988

Rosh Hashana. One of the holiest days of the year in Judaism. And I was in rehearsal for a show. To be a nun, no less.

I was invited to spend the holiday with David’s family and was pretty happy about this. I had met David a few months back in Central Park. We were both running the reservoir. We passed each other and smiled. When we passed each other on the second lap I gave him a flirtatious little wave, one finger at a time, then dashed out of the park. About five minutes later I heard, “Hey, wait up. Aren’t you the woman who was running?” I turned around to see David standing on the corner of Fifth and 90th Street catching his breath and waiting for my response. David said he was a little out of shape. He was a first-year surgical intern at Lenox Hill Hospital and spent most of his time off call asleep.

The adrenaline was pumping as I showered and changed at the rehearsal studio downtown. The show was rehearsing in New York, but would be running in Philadelphia. I’d be leaving town the following week for an open-ended run. I was superexcited about spending the holiday with David and his family. I hadn’t met anyone yet, and was told that everyone would be at his aunt and uncle’s, including Grandpa Max who was a little deaf.

We were to meet at five o’clock at his parents’ apartment off the park at West 92nd. Five o’clock sharp I arrived with a bottle of wine, a shopping bag filled with my tap shoes, and a big hand puppet that looked like a nun. A prop for one of my numbers.

His mother answered the door.

“Hi! I’m Kitty. Come in.” I was taken with this very attractive and svelte woman. The apartment was open and pretty too.

“You can put your things over there. David tells me you do something creative. What is it?”

“I’m an actress,” I said, hiding Sister Mary Annette. I stood for an awkward moment. “Uh—thanks for having me. It’s real nice to be with a family on the holidays. I’m working, and my folks are in Florida with my aunt and uncle.”

“A Jewish girl?” Kitty looked shocked. “With that light coloring and those blue eyes! Sid, come out here. Your son brought home a Jewish girl.”

Sid bounded from the bedroom adjusting his bow tie.

“Hi, there,” he beamed. “Welcome.”

Kitty went into the kitchen to prepare some hors d’oeuvres, and suggested Sid and I get acquainted. We sat on the big beige sofa.

“David tells me you’re a retired gynecologist,” I said. “My doctor’s on 79th and Park.”

“My practice was across the street. You know, Karrie, lots of my patients were artists. Writers, actresses, painters. Sometimes they couldn’t afford to pay me in money, so they paid me with their work.”

He pointed to several beautiful paintings that hung in the living room.

“I love these. We had more, but when we sold the house in New Jersey we couldn’t take everything. Actually, these mean more to me than the money.”

Kitty came in with drinks. We talked about my show.

“May I see what you’ve got in that shopping bag?” she asked. “I’m dying of curiosity.”

I pulled out “Sister” and let her sing a few bars.

“I love it when she projects her voice like that!” said Sid.

“You could give David some lessons,” said Kitty. “Speaking of—where is he?”

“I bet he’s asleep,” I said.

Kitty went into the kitchen to call.

“David works hard,” said Sid. “It was rough when I did it too. We’ve been getting lots of David’s mail. All sorts of literature on orthopedic surgery. I’ve been reading it all, so in my spare time I can become an expert on orthopedics.”

Sid was warm and proud.

“I know what’s next for you, Karrie. A white picket fence, a couple of children…”

“Oh, God,” I said. “I guess in time, but what would I do all day? I’d go crazy. I have to work.”

“You’re right,” Sid agreed. “It’s different now. A woman needs to work too. Right now Kitty works and I stay home. People need their own interests. Their own validation. A couple can’t be together twenty-four hours a day all the time. But having kids is great. My three children were educated right from the start. And this is the result. My son Greg is a CPA, Stew is a dentist and David is following in my footsteps.”

It was obvious his youngest was special to him. And David felt the same. The day I met David he told me he was having dinner with his “Daddy” that evening. He wanted to spend as much time with him as possible since his dad suffered a severe heart and kidney problem. Diabetes. Looking at this man aglow, I’d never have known it.

“I’m going to give David a buzz too,” he said. “Knowing him, he fell back to sleep.” As he moved toward the phone he looked at me. “Just wait. After tonight we’ll have you married off!”

“Oh!” I wanted to sound surprised, as if the thought had not occurred to me. However, I’d been thinking about it a little more seriously all summer. Well—not that seriously, and not with much intensity. A boyfriend, a steady boyfriend, a relationship, that was important. That was imminent. But marriage? When college ended, I considered myself too young. I was always “just in my twenties.” But now I was thirty. That was an age, as everyone made certain to keep reminding me. But more important, I liked how this felt. I liked David, his mother, and I was really liking his dad. They liked me, and art and culture. It was everything all rolled into one. And best of all, they lived in the city!

About half an hour later David arrived. His dad pulled him around in a big bear hug.

“How’s my boy? Sit down next to me and tell me how you are. You look great.”

I watched the two of them, side by side, and noticed similar mannerisms. Particularly a certain way they would convey comprehension.

“Uh-huh,” nodded Sid.

“Uh-huh,” nodded David.

I could see David thirty-five years from now. I began wanting to see David thirty-five years from now.

As we got ready to leave, David asked to borrow one of his father’s ties. Sid and I watched him knot the tie in the mirror.

“He’s the apple of my eye,” his dad told me. “I love all my children very much and never played favorites, but my youngest, this one, he’s the apple of my eye. I adore him.”

We went across the street to David’s aunt and uncle’s apartment for dinner. The table in their dining room was surrounded by family. His cousin, Paul, was there with his wife, Judy, who was seven months pregnant with their first child. We ate and laughed and enjoyed ourselves. After dessert Sid sat next to me and looked to his dad, Max, a psychiatrist who was talking with David.

“That’s Dr. Friedman Number One,” he said, pointing to his father, “Dr. Friedman Number Two,” he said, pointing to himself, “and Dr. Friedman Number Three,” he finished, as he pointed to David. “Three Dr. Friedmans!”

“Isn’t it nice to spend the holiday with your family, David?” Kitty asked several times during the meal.

“I remember when all these kids were little and running around this table,” said Sid. “Now everyone’s grown up and most of them live away. This is what’s left of the New York contingent. It’s up to this generation to carry on. Start the cycle all over again.” It was a warm family. Smart, cultured and most of all, welcoming. For the first time I realized the implications of being, virtually, an only child. I didn’t have much of a relationship with my stepbrother, Lenny, or his wife or kids. Unlike David’s family, with siblings and the promise of nieces and nephews and generations to come, in mine it would be up to me to start the cycle all over again. I was feeling eager to oblige.

The evening came to an end. We rode down in the elevator and said our goodbyes on the street. Sid walked over to me and David. “Take care of her,” he said. “She’s bright, she’s articulate, she’s a nice kid. Take care of her.”

Then Sid turned to face me. “Take care of him, okay?”

We all hugged goodbye. Sid looked at us once more.

“Take care of each other.”

“So…” I said, as David and I walked west towards the park. The evening was a complete success. I had been uncertain as to how things were progressing between us, and I thought tonight had clarified them. It certainly had for me. I knew where I wanted to stand. I turned to David, expecting him to put his arm around me with possession and pride. I had been completely accepted by his family. His dad. I smiled at him.

“That was fun,” I said, breaking the silence. “Thank you.”

“Yeah,” he said, putting his hands in his pocket. “I don’t make that much of these things. I’m glad you came though. I’m worried about my dad. Okay if we walk back to your place instead of a cab?”

There it was again. Nothing that said this is great and nothing that said it was over. We walked south on Central ParkWest toward my apartment on 78th Street. We walked in the relationship silence. Not the good kind where you know you can’t wait to get each other home and into bed, but the ambivalent kind. The kind where one person has more power because they know they’re the one who’s holding back. But they’re not telling you they’re holding back, and since you don’t really know this for sure, and you certainly don’t want to make a big deal out of nothing and create a problem that may not even exist, you decide you’re overly sensitive, paranoid, insecure. All of the above. You have no choice but to smile sweetly, keep your unspoken agreement in the relationship silence, and hope the other person will break it. That any second it will be broken by him seductively pushing you up against the bricks of the next building, off to the side of the burgundy awning, gently moving his hands across your cheeks, pulling back your hair and tenderly, deeply, passionately kissing you and kissing you and whispering in your ear, “Let’s get out of here. Let’s go home.” On the other hand, you could suddenly find yourself on 78th Street turning right to Amsterdam Avenue and wonder how you got there.

“David, do you want to come up?” The telling moment that can make or break it.

“Sure, I’ll stay.”

We rang for the elevator and I thought about the summer. One night in July I had just gotten back home after a weekend on the Cape. I felt really good, my skin was a little tanned and my hair had that great windblown look from sailing. I was wearing a pair of white shorts and a short sleeveless green tank top. My best friend Jane had come over. I looked at her when the buzzer rang.

“Expecting someone?” she asked.

The abrupt sound of the buzzer caught us in the middle of “haircut interruptus.” Jane had just gotten back from ten months on the road doing the lead in a national tour. She played a character in a fairy-tale musical where people appeared to be destined to live unhappily ever after. Despite her better judgment she got her hair cut in Detroit, just before returning to New York. We were in my bathroom pushing her thick black hair in every direction desperately trying to make it right. We had met on a national tour years earlier, rocking and rolling our way through high school in the fifties. Jane was full of passion and insight, loved her work and family. And even in the face of the haircut drama had the great vision to know that ultimately “it would grow.” I really admired her for that. I pressed the intercom and heard David’s sleepy voice.

“Hey—can I come up?”

“Yeah,” I said, before even checking with Jane. “That’s him! That’s the doctor guy. You’ll get to meet him.”

David came up to my apartment and had his bike with him. He had been riding around the city and missed me. I was very excited he showed up. But the excitement of surprising me, meeting my friend and telling me I was beautiful quickly evaporated, and the three of us just sat there in an awkward quiet till Jane said it was time for her to leave.

“I’ll walk you down to the lobby, Janey,” I said. “David, hang out. I’ll be right back.”

I stood in the elevator with Jane waiting for approval. Nothing came.

“So?” I wanted her to say something great about him.

“He’s cute,” she said.

“Yeah. He is, isn’t he? The dark hair and eyes.”

“And he seems to like you a lot.”

“Yeah? Yeah.”

The elevator opened and a couple with a little terrier got in. We stood in front of the glass double doors.

“What, Jane. You can tell me.”

Jane looked at me with eyes that said she wanted to be a good friend and didn’t want to hurt me.

“I’m just not a fan of ambivalent relationships,” she said.

“Oh. That.” My heart sunk. I knew she was right. I wound up missing David even when I was with him. He was far away when he was right next to me. Was it the hospital, his schedule, his dad, me? Or was it just David? When I went back upstairs David was already asleep.

Now, almost two months later, nothing between us had become any more clear. Except now I would be working in Philadelphia for an unknown amount of time. I decided the distance would be good. Our visits would be great. Absence makes the heart grow fonder. And I decided it wasn’t me, it wasn’t David, it wasn’t us and it wasn’t work. I decided David was just concerned about Sid.

He talked about his father our last night together before I left town with the show. “You do know, David, that you’re really lucky to have a dad like that.”

David knew. David also knew his father’s health was failing. So as the year progressed he did all he could to get through the intern program and make his father proud. But David was unhappy. He probably suffered more from sleep deprivation than unhappiness, but his undefined unhappiness gnawed at him. It colored our relationship gray. Murky. Ambivalent. Still, I wanted David. I wanted to belong to what seemed so appealing during the holiday. I spent the next six months in Philadelphia missing David, playing a nun and living like one.

In the spring David and I took a vacation to St. Barts. I had high hopes. The island was gorgeous and David and I were great travel partners. We rented a Jeep and he drove through the hills like James Bond. Every night we drank a bottle of wine on a new beach and brought in the sunset. We skinny-dipped and ate fabulous French food. We hiked and took a boat to St. Marten. We did everything you do on a vacation but make love. By the end of the week David went back into his ambivalent silence and we broke up on the plane coming home.

I was very sad to lose David and, as time went on, realized I was very sad to lose Sid. The night David brought me home from Philly, we stopped up to see Sid and Kitty. Sid had been in bed all day. His birthday party was canceled. He was not receiving guests. When we arrived, Sid came out of his room wearing a Dartmouth sweatshirt and jeans. He looked ten years older than when we had first met.

“Do you know how close Sid feels to you to be able to have you visit?” Kitty asked while I was helping her in the kitchen with the coffee.

Sid was quiet that night, but let me know how important I was. How good I was for David.

“I hope David thinks so,” I told his father. I wanted to tell Sid to make David stop it. To wake up. To open up and let go. But a father cannot do that for a son. A person can only do that for himself. I needed to think about me and what I was really getting from David, and not what I hoped I would get from David “if only.”

I called the Friedman house a few times after our breakup, and ran into Kitty once in H&H buying bagels. Then one night as I was drifting off to sleep, finally feeling better having turned the corner on David, he called.

“My father died,” David cried into the phone. “He was in his bed at home, in his sleep. I just saw him that day. He told me his disappointment in our breakup. He had told me I could never do better than you. I miss my daddy.”

David came over and we made love. Real love. Free and unencumbered, tender and a little wild. We decided to try again after Sid was buried. And it worked. For a little while. A very little, little while. Perhaps I represented a link David had to his dad. However, it did not make him more appreciative of me. He was just going through the motions. I was reactive. I would react to David’s moods. His advances and withdrawals. I twisted into positions like a Gumby, until I finally made myself stop.

David missed his father. I missed his father too. And I missed my father. My idea of a father. I sure loved Henry, but it never was a substitute for not knowing my real father. Mel had become a fictional character in my life. The clown who threw all the emotions of my childhood up in the air and juggled them like colored balls, unconcerned if they stayed up there or crashed to the floor.

In my mind, David had had the perfect suburban childhood. I assumed the love David received from his dad made everything easy for him. I assumed anyone who had a dad like David’s grew up happy. I didn’t get David’s darkness. I made an open-and-shut case that didn’t hold water. Perfect father equals perfect life. Not true. Nonetheless, I kept to my theory and hoped it would turn David into who I wanted him to be. And I thought my connection to David and Sid would turn me into everything I wanted to be. That it would erase everything Mel was unable to be. Mel. An embarrassment. My secret. On dark days, the likes of Mel made me question myself. Made me think I could never get a guy like David. But what was a guy like David? Only over time could I see that a guy like David wasn’t worth having.

Life moved on and I chose to keep David out of mine.