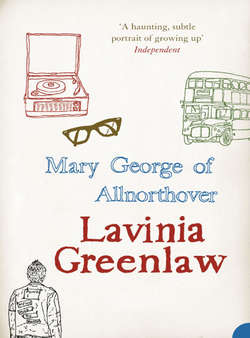

Читать книгу Mary George of Allnorthover - Lavinia Greenlaw, Lavinia Greenlaw - Страница 6

I

ОглавлениеOn 28th June 197–, Mary George of Allnorthover was seen to walk on water. It has to be said that the only witness was Tom Hepple, who was mad and had been away from the village for ten years until he turned up that very day, shouting. Mary had always been thought of as a peculiar child, but not one to seek attention. She had neither grace nor mystery and could not have wanted to become Tom Hepple’s angel, especially not the restoring angel he was looking for.

The house that Mary George woke up in was not one she knew. It was part of a straggle of Victorian cottages leading down to the station in Crouchness, built quickly from cheap brick that had now vitrified. The walls resisted hammers and drills, shed plaster, spat out nails and picture hooks. The rooms were low and dark. The front door led, in two steps, to a squat staircase at the top of which were two bedrooms Mary never saw. She had slept in a corner of the living-room, which was sallow and square.

The night before had been someone’s party. There were half a dozen people on the floor around her, including the boy who had been holding her hand as he closed his eyes. The others lay at odd angles, not touching, bent to whatever space they had found between the slippery three-piece suite, upon which nobody had attempted to rest, and the smoked-glass coffee-table. Where the shaggy carpet had been scorched, its nylon thread was gluey and fused. The floor was scattered with crumpled cans and plastic cups half full of dog-ends and vinegary dregs. There was a bowl of cornflakes someone must have thought they wanted.

Mary sat up and reached into the bag she had used for a pillow. The right lens of her glasses was cracked but she put them on anyway, and moved towards the boy. He lay on his front, sweating gently inside what might have been his grandfather’s pinstripe suit. Mary crouched over him, her left eye squinting behind the one good lens. He had pulled up his right leg and stretched his right arm forward. As if swimming or flying, she thought. Mary studied the bones of his wrist and ankle, exposed by the too-short suit. His long fingers had a delicacy at odds with their large, rough knuckles.

The boy’s hair was thick and wavy, both dark and fair. It was brown where it was shaved high at the back of his neck and blond in the matted fringe that obscured most of his face. He was flushed and open-mouthed. Mary concentrated hard and, steadying her glasses with one hand, moved the other towards his cracked lips. In the sour still air of the room, the rush of his breath startled her. She lost her balance and fell back, knocking over a tower of beer cans. Their clatter was surprisingly dull and Mary had stuffed her glasses in her pocket and left before anyone else had properly opened their eyes.

Crouchness sat on the point of the estuary where clay gave way to mud. It was the first or last stop on the London line, a town built on fishing and coastal trade, now propped up by light industry – packaging, canning and printing. The clapboard sail-lofts perched on stilts along the shore were empty, too high to live in and too draughty to use as stores. The locals had been expert sailors in these shallow waters. They had known how to navigate the narrow passages between the sandbars that riddled the low-lying east coast. They had hauled in so much herring, some had been barrelled, salted and exported to Russia. In the summer they had crewed on yachts, their local knowledge keeping the gentry from getting stranded. They had earned enough to buy their own homes.

There were boats still, a handful of dinghys owned by local lawyers and doctors, a couple of dredgers and a light-ship that had become obsolete five years ago and was left moored in the docks, a heavy-bottomed ark slumped in the mud at low tide.

Mary walked down to the shore and out along a path on top of the dike. The ground here was neither earth nor mud, but something in between, greasy, compacted and dark. It was five o’clock in the morning, bright and warm in a tired, dusty way like the end of a hot day rather than the beginning. Soon, this heat would concentrate itself once again and people would get out of bed to open windows that were already open.

Mary had slept in all her clothes: a heavy ink-blue twenty-year-old dress and a stringy dark-red cardigan she had knitted out of synthetic mohair on the biggest needles she could find. It had no buttons and so she habitually clutched its edges together in her fist. She pulled the cardigan off and stuffed it in her bag, an army-surplus knapsack with a slipping strap. It came loose and banged around her knees as she walked. Her feet sweltered in heavy boots. She tried wearing her glasses again but seeing the cracked path and wilted grass made her feel even hotter, so she put them away. Squinting back inland, Mary could not tell the creeks and the banks apart, they ran in and out of one another so and nothing shone in a way that suggested water. The town was a blur of grey, like a model waiting to be painted. It had long been stripped of its colour by salt and the winds that blew in ‘straight from Siberia’, as everyone said, not wanting to think such icy cold could be local.

The mud gave off a stink of burning tyres, ammonia, diesel and harshly treated sewage, nothing natural. What life there was, was amorphous, useless: lugworms and silted shrimp. Further up where the coast broadened out into the sea and the edge of dry land was definable, there were lobsters, samphire and crab. Boats put out to sea and did battle with Icelandic fishermen over cod. That was where people went to open their lungs. Crouchness had the only kind of sea air Mary really knew and she tried hard not to breathe it.

It was almost six o’clock. Mary turned back towards the town, hoping for the milk train. When she got to the top of the station road, she found she didn’t want to pass the house where the party had been. The boy might have woken. They had been sitting together on the floor talking. Each time their eyes met it was harder and for longer, and then there had been a few vague kisses during which his hand moved to stroke her cheek, then dropped to her thigh and they had both stopped and looked down. He stared, as if the hand on this strange girl’s skirt were nothing to do with him. Mary stared too, wondering if she should move it, and if so where to? By the time she had got up the courage to hold his hand, he had fallen asleep and she stared at their hands until her eyes closed too.

There was a row of allotments on the embankment through which Mary could reach the railway track and then the station. She climbed over the gate and collected peas and raspberries, stuffing some in her mouth and some in her pockets. They tasted like steel wool. She wandered along the narrow mown strips that separated each plot. Clipped borders, raked earth, intricate constructions of bamboo, netting and tags were maintained by gardeners unwilling to alter their routine according to the failure of their enterprise – blown courgette plants, yellow lettuces, tightly curled buds that had been scorched before they could open. Mary caught her leg on a tap hidden in a clump of grass. She rinsed off the blood, cupped her hands under the trickle of water and drank. It was tepid and tasted of lead, as if it had been tinned years ago.

At the track, assuming there had to be a live rail, Mary put on her glasses. Nothing suggested electricity. At least seeing made her feel she could hear, so she would know if a fast train was going to swoop round the bend, blaring out of silence without warning, to catch her as it had caught the child whose bicycle had got stuck or the boy who had fallen while spraypainting a bridge or the woman who had just lain down. But who were they? No one she’d met had ever known them. They were just good stories. Mary crept over the lines.

The ticket office was closed. The guards’ room and toilets had been padlocked and abandoned. There was a waiting room with a door jammed only just open. Its one high window was locked, broken and brown, as if someone had taken the stale chocolate from the vending machine and smeared it all over the glass. There were timetables but it was too dim to read them and there was no bulb in the fitting that dangled from the ceiling.

A goods train came through with two passenger carriages attached. Three people got out, the heavy doors slamming behind them with a lethargic clunk. Mary climbed on board. The luggage rack above her sagged like an old string vest, the walls of the carriage were waxy and peeling, and the seat smelt of cardboard and milk. This is like travelling in the back of a cupboard, she thought. She tugged at the window till it gave an inch, then fell asleep.

The train turned back on itself, inland along the estuary with its cargo from the industrial estate of Crouchness: bundles of angling magazines, promotional packs for a new car, dog biscuits, gift jars of sea salt and printed t-shirts. All this had been brought to the town as paper, ink, bonemeal, cotton, minerals, bottles and labels. It came with instructions, was put together and sent back again; nothing was made or remained in Crouchness, let alone thought of there. This was the milk train but it carried no milk, which was delivered by tanker. Sacks of post were still thrown on and off at stations near main sorting offices but most of that, too, now travelled by road. So there were fewer trains each year and the rolling stock was left to seize up on the sidings, to struggle through these slow, pernickety journeys, stopping at empty platforms and once in a while, at dawn on a Saturday morning, bringing a girl like Mary nearer to home.

Once out of the marshes, the train continued its stop-and-start journey through the inland towns. The flatness of this country was suited to the new large-scale arable farming. Trees had been felled, hedgerows pulled up, ditches filled, footpaths shaved away. A single field could be all there was in sight. The only interruptions were those forced by the twisting lanes, the untidy hamlets and scattered woods. Around here, things had always been small-scale, local, instinctive. To the north, the land was even flatter. There were long stretches of Roman road, few trees and even fewer houses. The farming was better there.

As the land had been opened and pared away, the old buildings of the landowners once again dominated the view: extravagant brick chimneys and wooden belfreys embellished manor houses, farms and churches that had been poised to be seen and to be able to see for miles. In a place like this, though, distance was more vertical than horizontal. Nothing could look important under such huge skies.

The guard made his way down the train. He was sure that someone had got on and that they would not have a ticket. He opened the sliding door, sauntered through and stood in front of the sleeping girl, rocking on his heels like a policeman savouring a trivial caution. He paused for a moment, wondering which excuse she would try: the dropped ticket, the lost purse, passing herself off as foreign or dumb. Or asleep? Was that it? Those ones usually overdid it though, giving themselves away with little touches like snoring or a dropped book. This girl was hunched in the corner of her seat, her head propped on her knees, her hands in fists clenched in her skirt. She looked like someone waiting for a bomb to drop; so much unlike anyone sleeping that the guard was inclined to believe she really was. He shook his head at this small, bony creature dressed up in clothes that were too big and too tatty, and those ridiculous boots. She would trip over everything. She had a slapdash boy’s haircut and a furious face. He was about to laugh, cough and wake her up, but had left it too long. He could not think what to do, so turned round and crept away.

Mary woke up as the train pulled into Ingfield, from where she could walk the three miles home. She followed a string of pylons to the reservoir, along unsigned footpaths shaved to ridges. Withered stalks scratched at her legs. The earth was going to be changed by this drought for ever. The deep clay that had sealed these parts in the wake of a glacier thousands of years ago, was now brittle and fractured. Powdery top soil lay across the surface like dust. When the weather finally broke, it would be blown or washed away.

There was a point where this landscape buckled on a chalk seam and rose and fell in a ridge. Mary climbed and found herself looking down onto the conifers that shielded the water. From up here, she could see the bleached concrete rim that ran along that side of the reservoir’s basin. The water was hard to get to. A chain-link fence ran around most of the perimeter and there were just two gates – one for those with fishing or sailing permits and one for the Water Board. At the point closest to the road, there was a path leading to a viewing platform. The noticeboard on the platform offered a key to the birds that could be seen there: cormorants, herring gulls, herons and Canada geese – sea birds, migratory birds, making do. There was a list of statistics, too, that explained how many cubic metres of water served how many businesses and homes, how much earth had been moved and concrete poured, and how many trees had been planted.

Mary remembered her father coming on a visit when she was ten. It was March, around her birthday. Her mother, Stella, had taken her to Ingfield to meet him. Matthew had arrived with a thermos and a pair of binoculars, and reminded her that a year earlier she had declared herself interested in birds. He drove her out to the reservoir where they stood in silence on the viewing platform in the searing wind, fumbling the binoculars between them with deadened fingers. To break the silence, Matthew pretended to have seen a heron. When this didn’t excite Mary, he spotted a kingfisher, then a hummingbird. ‘Look! Look!’ he had implored but she wouldn’t join in, wouldn’t pretend and had refused to take the binoculars from him.

Tom Hepple held his breath but still his heart would not slow. He tried not to gulp air as his arms curled and his hands went dead. He leant hard back against the tree, wanting to feel his spine, to know he had bones and could stay standing and would not break. His heart was beating so fast it had to burst, it would be a relief if it burst. When it seemed it might, there was a hollow pause followed by erratic threes and fours, not a light palpitating skitter now but slow hard thumps, like bubbles rising in something solid, a knot surfacing in a piece of wood. This was worse than anything.

He had known about the water and had come back knowing what he would see: no Goose Farm, no Easter Bank, no home. Tom knew, too, that there would be concrete, fences, fir trees and a bowl of water that stopped the eye in its tracks. These were places where you traced a slope up and over but not down because a bowl of water stopped you, cut across your vision, and even when there was no reflection, turned you hard back on yourself. Reservoirs never became part of things. The eye told you first and then the land. You could walk, as Tom had just done, to the water and, look, there were fish and waterfowl, and the trees grew happily over the edge but it didn’t make sense. Least of all here, where the world was flat and the dip below Ingfield Rise had been a place to get out from under the sky.

Tom was scared. If he could just find the house, know where it was. He crouched down and pushed his hands into the earth wanting to feel the full force of the world push back and steady him, but last year’s leaves and pine needles were loose dust. He felt the bubbles escape his chest and press into every part of his body. He tried to hold harder to the earth. I will float away, he thought, as each wave of panic left him with less and less sense of himself. I do not work, I am not flesh, I am light and air exploding.

And although Tom believed this, he settled slowly back into himself, his hands were his hands again and his heart forgotten. He decided to try once more. The hard light hurt his eyes as he emerged from the dullness of the trees. He concentrated, turning his head from right to left until he could be sure that there was the Ridge and Temple Grove marking the edge of Factory Field. He followed the land down without thinking and fixed his gaze on the point where the house should be, just past the fishing jetty, only five yards or so out now that the water level was so low. He walked towards it, bumping and stumbling but looking neither away nor down. It was no good, there was nothing to fix on, just the inscrutable dazzle of sun on water. The harder he stared, the more it kept shifting and shimmering and pushing him away. Tom reached the jetty and made for the shadows beneath it.

As well as being shortsighted, Mary had no sense of direction. More accurately, she had a strong sense of counter-direction and would set off cross country absolutely sure of herself, walking miles the wrong way. On the way home with her best friend, Billy Eyre, she would argue fiercely about which path to take, which corner of a field the stile would be in, that the road they wanted lay just beyond it. She was always wrong and Billy would put up a fight but secretly encourage her, enjoying the angry surprise on her face and the sulky calm that followed. He would go as far out of their way as she led him.

This morning Mary was tired and although it was only eight o’clock, the sky was not easy to look up into. She had walked for a mile without going wrong, as if not thinking about it kept her from losing her way. Beyond the reservoir was Temple Grove which gave out onto The Verges, which would in turn lead her home. The simplest thing to do was to walk round the water. It might be cooler, too. Mary made her way through the trees and found what was called the Other Gate, not the locked entrance to which licensed anglers had a key but a panel of the fence a little further along that had been expertly loosened and replaced. Even those with keys found it easier to reach the jetty this way, especially now that the lock on the real gate had grown so stiff. Mary heaved the panel a little to one side and slipped through.

The drought forced things open and they gave up whatever was once liquid inside them: the parched trees smelt of resin, the fence of solder and the jetty of creosote. The reservoir, though, had withdrawn into itself. Mary took off her boots, walked to the end of the jetty and sat down on the edge but it was no good, her feet could not reach the water. She walked along to a clump of trees.

Mary and Billy used to climb out along a low bough here. He would watch her take off her shoes and glasses, and walk swiftly to the end only to have to come back, take him by the hand and inch him along. Mary tried to explain how she could make herself light and steady by not looking, by insisting that there could be no wrong step, what it was to keep moving, not knowing when she had left the bank and was out over the water. Billy had tried once, without success, to get her to do it with her glasses on.

A girl had appeared in the tree over the house. She was standing up straight on the low bough, her arms spread wide. In quick, small steps she reached the end. Tom’s eyes followed her, went past and looked down and there was something, a shadow, like the darkening colour of a sudden change of depth. As Tom stared, the shadow took on shape and then it wasn’t shadow but a house, lingering like a deep-sea creature uncertainly beneath the surface. Its slate roof glittered for a moment and was gone but the girl was still there, not in the tree now but further out, where the roof had been, on the water.

A pale thing with cropped hair; a child in an old blue dress that might have been his mother’s. She was somehow in suspension, utterly concentrated but also on the verge of slipping away. Tom started to walk towards her, terrified he would make her disappear. Don’t move, he begged her silently, not till I get there and see where you are. But then he was crying and could not see, and the sun shifted, enlarged, glared, and somehow he had closed his eyes and when he opened them he was by the tree and there was a barefooted girl but she was beside him.

‘You frightened me.’ She leaned a little towards him, squinted and frowned. ‘Oh! I’m sorry, I didn’t recognise you.’ He didn’t look up. ‘Are you in pain? Have you hurt your eyes?’

‘Are you from here?’ His voice was an uncertain roar. He had spoken to no one for days.

‘Oh! I’m afraid … I thought you were someone … I’m sorry!’ Embarrassed, and a little frightened, Mary turned and half walked, half ran to the jetty.

Tom could not move and did not know what to ask, but just as she disappeared he realised: ‘I know you!’

Mary, pushing on her glasses and throwing her boots over her shoulder, scrambled up through the trees and squeezed through the Other Gate. She heard another croaking shout as the loose panel fell to the ground with a clatter and twang, like tired percussion. She ran up the track, her bag banging against her knees, one hand pushing her glasses back up her nose. She stopped to shove her feet into her boots. There was no sign of him following, but Mary cut across Factory Field. Her panic was so great that she felt her body drag, as if the corn were as tall as it should have been and she was having to fight her way through slapping waves. She stumbled over the stile and down into the road.

As soon as Mary turned the first corner, she began to calm down. Her cheeks stung, each gulp of air caught like chaff in her throat and she could run no further. It was the reservoir that had panicked her, she decided, its artificial plantations and still water, not that man who looked so worried and ill. Her mother would have held his hand and talked to him in her cool, soothing way. Mary knew what that felt like: like being rescued not by an angel but by a statue of an angel, and folded in marble wings; and she had mistaken the man for someone she had thought of as a statue too, when she was a child, a church saint or an effigy on a tomb.

Mary skirted Temple Grove, a copse of spindly, tangled hazel, ash and willow: useful, adaptable, flexible trees that had been part of a parcel of land given to the Knights Templar after the first Crusade. The Knights learnt Euclidean geometry from the Arabic, and applied it to the building of their barns. While their wattle-and-daub farmhouses had lurched, buckled and been pulled down, these barns, with their perfectly balanced angles, were still standing. Nothing so regular had been built until the new houses after the last war, tessellated arrangements that had everything to do with numbers.

The Knights had prospered for a hundred years in austerity and chastity before the parish turned on them when the crusades failed, with accusations of idolatry, homosexuality and child murder. There was still a whiff of that six-hundred-year old scandal about the place. Saplings struggled up through nettles and brambles, only to give up before they emerged from the shadows. The wood was dark and difficult to find a way into. Those who wanted to walk their dogs, pick blackberries or bluebells, or tire out their children, went out through the other end of Allnorthover and into the Setts, a solid wildwood of oak, chestnut and beech with wide paths and clearings, National Trust signs, and bamboo and rhododendrons that made it seem like nothing more than an overgrown garden.

Temple Grove was where you went to build a den, try your first cigarette and, later, to drink cider round a fire, smoke dope and scare each other with stories about the Man in the Van and his goats, or about the day someone found a makeshift altar here, three bales of straw, a black candle and a chicken’s foot. Billy and Mary had done these things and had heard all the stories. Neither of them knew who was supposed to have found the altar but they believed it. Once, they had found a full set of women’s clothing, including bra and knickers, next to three old sofa cushions. The cushions had been ripped open and scorched.

At some recent critical point, Temple Grove had become too small to hold secrets. It lost a little more of itself each year, as the farmers pushed the fields harder against it. Children went in knowing they could be out in under a minute, that they could always be heard and could hear their friends calling from the road or the field. Ingfield Dip was full of water, the Grove was half gone, mile after mile of hedgerow was being uprooted and clusters of new houses were springing up all around, with new windows from which to be seen. Where was there to go now, not to be visible?

There were people living right next to the Grove now, too. The Strouds had sold off land for a caravan site called Temple Park that the villagers preferred to think didn’t really exist. But like the hospital, the courts or the Social Security office, most people had a connection with the place at some time or other: a friend or relative needing a cheap rent or placed there by the Council. The village was growing older as the old lived longer and the young moved away. Like the two cemeteries, the almshouses were full. A senile widower, a pregnant daughter, all those who might have been cast out or taken in, or sent to an institution, another town, another country, found themselves here. They lived quietly and came to the village as little as possible, mostly to get the prescriptions that helped them sleep, walk or breathe.

The caravans were set at odd and irregular angles, as if to suggest some spontaneous arrangement or natural development. Packed close together, they were turned away from each other as much as possible, and were painted in unobtrusive shades of pale green, beige and grey that matched the worn grass, gravel and cement that defined each plot. The caravan dwellers took on this drabness and were recognised by it. They made cramped, effortful gestures and their skin had a greenish tinge, as if they brought with them the light of their evenings squeezed close to their televisions.

When the heatwave started, they began to leave their doors open all night. Then they took to unclipping their tubular aluminium folding tables and chairs, and taking them outside. They began to have their meals outdoors, first in the evenings and then at breakfast, too. They neither disturbed nor joined each other. Couples sat down as usual to talk about the children, the bills, a holiday, an illness or the weather. They would remain, only yards apart, within the privacy of their small square of grass. The heat opened the pores of their skin; sweat made them conscious of their breasts, bellies and thighs; their clothes were tight or heavy. The secrets, confessions and ultimatums that might have surfaced got stuck. No marriages were saved or broken. By the end of June, the tables were making way each evening for mattresses, lilos and camp beds, but only after dark. At dawn, everyone crept indoors to dress with the guilt and pleasure they might have got from staying out all night unexpectedly.

Mary crept along the paved road that wound from one end of the site to the other. She passed a couple folding up their camp beds and a young mother gathering sheets, her naked baby fast asleep on a pillow beside her. If they were taken aback by Mary’s presence, she didn’t notice. She probably didn’t even see them. Mary’s glasses were the smallest, least obtrusive she could find, but still they weighed upon her heavily. There was too much, anyway, between her and the world, without those thick lenses. They corrected her vision, but she could not feel what she could see. So Mary tended to keep her head down and imagine.

Beyond Temple Park was a small breaker’s yard, the size of a meadow in which a family might keep a pony. It was just a worn-out patch of oil-stained earth, now dried and cracked and hardened by the heat. There were always a few cars dumped along the back hedge, mostly those that were too big, too small or too gimmicky, a Humber perhaps or a Robin Reliant. Some were picked away, scavenged for spare parts; others rusted and sank into the ground. The yard belonged to Fred Spence, a compact and taciturn man who lived with his wife in one of the smallest, oldest caravans in Temple Park. He kept a filthy truck parked in the yard and drove away in it, early each morning. Fred was often gone all day but rarely brought anything back. Mostly he dealt in incidental scrap – guttering, a trailer, a gate, pipes.

Fred Spence’s wife spent her days cleaning and when her home was done, she’d scrub and polish the outside of his ‘office’, a tiny outhouse with a single window. She was not allowed inside and nor were Fred’s customers. On the rare occasions that money changed hands in the yard, Fred entered his office and opened the window to receive it. Dorothy Spence was not allowed to touch the truck either.

In those long days of fierce light, Dorothy Spence could not stop thinking about glass and, in particular, windows. It had become too hot to keep cleaning her home so she worked on the outside, preferring the parts that give her a glimpse in. Mary George met her at the yard gate. She barely recognised the woman she saw on the bus into town with her line of lipstick, and bright hat and gloves. To Mary, without these accessories, Dorothy Spence had no mouth or hair or hands.

‘You’re the George girl? I thought you were your brother.’

‘I have no brother.’

‘Sometimes you look like him.’

‘Can I help you carry those?’

Dorothy Spence took a step back, ‘Thank you.’ She shook her head, scrutinising Mary, before adding ‘You need a good wash, my girl,’ and was satisfied when the child did not protest. She walked carefully away, a bucket of dusters, brushes and cleaning fluid in either hand. Mary watched her begin to polish the windscreen of a crumpled Ford Cortina.

Mary’s pale face was lit with pink across her cheeks and nose, a livid colour that looked not like sunburn but some internal heat. Her fringe fell limply into her eyes and so, to keep it off her face, she took a red scarf patterned with dark gold flowers out of her bag, tied it round her head and set out to walk the last mile home. The makeshift turban made her both majestic and menial, a boy king or a kitchen maid. Her clothes looked accidental, borrowed or found, all of them ill-fitting and far too heavy.

The Verges had ten clear yards of mown grass on either side. In the days when roads like this were a favoured route for merchants, robbers and highwaymen lurked among woods and between villages. A statute was passed, decreeing that all trees and bushes be pulled up so that they would have nowhere to hide. Now, this sudden width had a vertiginous effect on drivers who had crept out of the traffic snarl of Camptown, or had been driving under the limit through Allnorthover on a speed-trap day. The widening landscape encouraged them, and there were many accidents as the road was really quite ordinarily narrow and its corners particularly nasty, not the gentle sweeps they appeared at all, but full of odd angles that caught you off guard. The Verges curved slyly back and forth and then the road straightened, the banks disappeared and the village of Allnorthover began with clusters of small tied cottages set hard on the road. It was at this point that Mary saw the man again. She had been walking along the bank close to the trees, trying to find some shade. He was standing quite still at the point where everything narrowed again, facing in the direction of the village.

Mary could not think why he was there. The air prickled around him, as if he were at war with every muscle and bone in his body. She felt his pull and disturbance but did not want to know what it was he wanted. She crossed over the road and walked quickly past, willing him not to notice her.

Tom had almost reached the village when the road went bad on him. He felt his legs billow and contract, making contact with the road more suddenly or later than expected. He had been waiting for the ground to settle when the girl appeared in front of him. She did not look back but Tom sensed that things cleared around her. He followed her. When he could not catch up with her, he began to call. Feeling his voice raw and uncertain, he put what strength he had into making a noise that might reach her but could manage no more than a string of single sounds.

So it was that the villagers of Allnorthover saw Tom Hepple come home, walking down the middle of the High Street, looking more than ever like someone in the grip of a god, only he appeared to be fixed on Mary George, who was falling over herself in her hurry to get away. Tom was half singing, half croaking one drawn-out misshapen word after another, ‘Wait! Stop! Help! Home!’

Mary would not let herself even imagine him. Looking neither right nor left, she passed the first houses. At the Green, she broke into a run and pushed open her garden gate. Her mother was just opening the door when Mary flew past her. Stella was about to follow her up the stairs when an odd howl came from the Green. She turned back and there was Tom Hepple, just a few feet away. He still looked like the visionary, the genius she had once thought him to be, with blazing eyes and fine bones emphasised by his thinness. He did not look like someone who could have a crude, simple or mistaken thought. But Stella was ten years older than when she had last seen him, and the difficulty of those years had made her more careful. His face was burnt and lined, and his black curly hair, grey, cropped and coarse. Stella saw how his elegant fingers (‘Musician’s fingers!’ his mother Iris had called them) waved constantly and pointlessly in the air, that his hands could no longer hold or control anything, that his eyes were screwed up with the effort of keeping in focus. She remembered. He was a force, a hurricane, sweeping things up, breaking down doors, sucking people in and under. Stella knew right away what he wanted.

‘Tom, my child does not remember you.’

‘Your child?’ Tom’s fingers scrabbled and danced as if he were solving an elaborate equation. His voice grew quieter as his mind calmed, able at last to make connections. ‘I forgave … I could come back … She showed me!’ Tom, who had been staring into the sky all the time he spoke, brought his head slowly down and fixed his gaze on Stella. His voice swelled again, ‘She walked out on the water! Because I was there! To show me!’

‘The house?’ It took a moment for Stella to admit to herself that she knew what he was talking about. Then that ten-year-old winter sprang up around her like buildings cutting out the light. She remained silent, as did Tom, whom the past had never ceased to assail and confine in this way.

‘Mrs George!’ An exasperated voice was calling to Stella from the bus stop. There was a sound of old brakes being applied too fast, followed by a tentative rumble and then another long screech. A bus was juddering along the High Street, stopping every few yards.

Violet Eley emerged from the shelter. The light found nothing to play on in her pastel clothes, hard white hair and thickly powdered face. She had seen the mad Hepple brother come stumbling into the village to stop at Stella George’s garden gate. To her relief, the bus had appeared on time and she could get away from whatever scene was unfolding. But the bus had begun stopping and starting and, sure enough, there was Stella George’s dog, Mim, sitting in front of it in the road. Violet Eley’s impatience overcame her distaste. ‘Mrs George! This is really too much! I have a train to meet!’

The bus started up quickly, crept forward and Mim gave chase, barking furiously, darting in front and snapping at the tyres. The bus stopped again and the dog sidled onto the pavement. The driver climbed out of his cab and got as far as putting his hand on Mim’s collar. She did not snap or growl but set up such a grating, unbearable howl that the driver let go immediately. Seeing Stella by her gate, he approached, shaking his head.

‘Your dog … please … should be tied up …’

Stella kept her eyes on Tom Hepple who was staring past her now. ‘Bring the dog here,’ she said, knowing he couldn’t. The bus driver had noticed Tom by now and was full of confusion. ‘You know how she cries …’

‘Mrs George?’ Violet Eley pleaded.

People on the bus who were to get off in the village had wandered into the road. One or two tried to move Mim, who yelped as if she had been run over and cut in half. They recoiled, terrified in case anyone had seen them and would think they had inflicted pain on the animal. Those who knew Mim ignored her. Strangers or not, they all came across the Green to where Stella George willed Tom Hepple away from her daughter, and Tom Hepple stared through her walls and windows, and the bus driver and Violet Eley stood as if caught in their spell and miserably rooted to the spot.

‘Someone get Christie,’ Stella managed at last, and the spell was broken. The driver returned to his bus and helped Violet Eley on board. The others faded away. Then Christie Hepple was there. He was as tall as his twin brother but bearded, full-faced, not yet grey and far more solid. He stood to one side of Tom, as if he were his shadow – one that had more substance than the person who cast it. Christie put his arm round his brother, talking softly and constantly in his ear until Tom loosened and leant into him, turned and was taken away. Christie had not even glanced at Stella, who watched them out of sight. Then she walked over to Mim, picked her up in her arms and carried her home.

Tom had not been staring up at Mary’s window as he thought. Her room was at the back of the cottage, overlooking a small garden and endless fields. The old plaster walls bulged between the laths; the wooden floor tilted and creaked, its unpolished grain worn to a shine. There were no shelves, so Mary’s books were stacked in precarious towers that she frequently upset or that grew too tall and toppled over. They were mostly her father’s. Reading her way through them felt like climbing to his door.

This had been Mary’s room all her life and something remained of each of its incarnations. Her only methodical change had been to replace each panel of an alphabet frieze with a face cut from a newspaper or magazine. These were black-and-white pictures of singers, film stars, artists and writers – anyone Mary liked the look of, so long as their names matched a letter she hadn’t covered yet, and they were foreign and dead. The panel Mary had painted black ended just below the flowers her father had stencilled, rows of daisies she had insisted upon when, at four, she first went to nursery and saw other girls, and tried being like them for a while.

The sun passed easily through the orange curtains Mary had drawn across the open window, and coloured everything in the room that was so black and white. She held up her arms and examined them with pleasure, seeing her pale skin suddenly gold. She drew her hands to her mouth and breathed hard, to remember what it had felt like when she had reached out to the sleeping boy. Mary stretched and curled, feeling ease and pleasure and a lazy excitement, sensations that were all more or less new to her.

That summer, the exchanges and balances of the oil export market went awry. The countries of the Middle East, having been bent to whatever shape the West demanded, consolidated. The price of a barrel of oil changed by the hour, doubling and tripling. At one point the figures on the Stock Market board trailed a string of numbers like the tail of an ominous comet. Petrol refineries searched the world over for other sources but were still dependent on the rich fields of the Emirates. There were queues at garages, even battles. People walked sanctimoniously or furiously.

Fred Spence’s brother, Charlie, had to get up earlier each day. Once a week, the man from the company came to fill the well beneath his two petrol pumps. He received a fifth less fuel than usual and was given a price to which he painstakingly altered the plastic push-on numbers on the board on his forecourt. The company sent a letter that explained what the government said. Petrol was to be rationed.

Charlie’s bungalow sat behind the garage and he could hear the cars pulling up in a queue before he had got out of bed. As impervious to the heat as he was to the revving engines and tentative then impatient horns, he fried his year-round breakfast. Charlie took his time, stopping to clean his heavy black-framed glasses and to grease back his hair. He was fifty now and while his florid face had settled in folds and pouches, he persisted in the look he had established during a brief period of interest in such things, twenty years before. He sent off for small bottles of unlabelled black liquid by mail order, to dull the grey in his quiff. He wore indestructible synthetic shirts in garish geometric prints that stretched over his sagging breasts and belly. Charlie didn’t worry about the petrol crisis but went by the figures and instructions he was given. He felt no joy in his newfound authority either, simply telling angry customers that ‘The government says …’

When the clock reached seven thirty, he opened his front door. The fetid air of the bungalow, its trapped smells of fried food, cigarettes, sweat and aftershave, lingered on the forecourt most of the day. Charlie blinked, his only response to the sun. It was a Monday morning and the commuters were there, wanting to be gone in time for the city train. Once Charlie had filled their tanks, they relaxed and said good morning as they turned the key in their ignition. It would occur to those who worked in international banking or on the trading floor that Charlie was, of course, in the same game. They made fraternal, esoteric remarks about indices and monopolies. Charlie was polite: ‘The government says …’ He nodded as they accelerated away.

Allnorthover had two bus stops. A brick shelter with wooden seats and a tiled roof sat in a paved square on the edge of the green near Mary’s cottage. There were rarely many people in it as this was the stop for buses going only to Mortimer Tye, where you could do little more than catch a train. A hundred yards along the High Street, on the opposite side of the road, was the stop where you waited to go into Camptown, where Mary went to school. Here, the Council had recently erected a tin shelter, a single wall with a narrow roof and a plastic ledge on which to sit. It was like an open hinge, already tilting as the paving stones had begun to erupt. The pavement was squeezed between the road and the thrusting hedges of the long front gardens that kept the village’s bigger and better houses – square, butter-coloured Georgian villas – out of sight. While the older cottages and shops built on the road had long ago grown dull with dirt from the exhaust fumes of lorries, their windows permanently filmed with dust, the villas gleamed.

The fuel crisis meant that the first three morning services into Camptown were reduced to a single bus that came at eight. Pensioners who usually had to wait till nine o’clock to use their passes were now allowed to travel early and so this morning, six elderly members of Allnorthover’s First Families – Laceys, Hepples, Kettles or Strouds – headed the queue. The women wore nylon gloves and lace-knit cardigans over loose floral dresses made from the same material they used to make stretch covers for their chairs. The men dressed in suits that had been so well cared for they were worn to paper, their creases to glass. They wore caps they had had all their adult lives. Married for fifty years or more, couples like the Kettles rarely looked at or spoke to one another but once in retirement, weren’t often seen apart.

Mr Kettle squinted into the sun at this arrival, a child in old man’s clothes, a singlet and baggy flannel trousers, held up by braces and gathered in a wide leather belt. ‘That a boy or a girl?’

‘It’s the George one.’ Mrs Kettle shifted her weight from hip to hip by way of greeting. Behind the Kettles were some Hepples and Strouds. Spreading themselves just a little, they filled the shelter, taking whatever shade it could afford.

Behind them were the early workers, who usually caught the seven o’clock. They worked the first shift on the industrial estate, making the fruit juice, electrical goods and sausages for which Camptown was known. The early workers were used to being able to sit apart in a bus that arrived empty. Each took a seat by the window and set down beside them a sandwich box, flask and bag of clean overalls. They came home together, too, just before the end of the school day, with their overalls back in their bags with their stains, the bright splashes of pig’s blood and artificial orange, a whiff of something sweet and rotten or sour and citric. Only men worked in the electronics factory. They smelt of nothing and told their wives that the holes in their sleeves that had been eaten away by hydrochloric acid were cigarette burns.

The early workers stood uneasily in single file while beyond them, school children spilled onto the road. The youngest were hot and already bored of pushing each other into hedges or playing chicken with the juggernauts. Two older girls lolled against a fence. Mary tentatively joined them.

‘Says you were followed by a loony, Saturday …’ a Lacey girl began, her doll-face turning sour. She primped her blonde curls. ‘Your type?’ Her mouth, already a tight purse like her mother’s, clasped in a satisfied grin.

Mary laughed and shook her head, half-heartedly. ‘Right nutter.’

Julie Lacey looked her up and down, unconvinced. ‘Student, was he?’ Then she turned suddenly to a plump girl on her other side. ‘Says your uncle, June!’

June Hepple swung her lowered head slowly from side to side, ‘Nothing to do with me …’

Mary looked at June’s quivering cheeks, her vague brown eyes, her frizzy hair pulled back in a tight ponytail. She didn’t know whether she wanted to comfort or shake her. Mary took a book out of her bag and sat down on the kerb to read. Julie Lacey nudged her book with her toe. ‘There’s dirty … dogs and that …’

The buses were old double-deckers with an exhausted and complicated rumble that everyone living along the High Street could recognise. They rarely bothered to leave their houses to catch one until they heard it coming. Mim began barking long before the eight o’clock pulled up, already half full. The Kettles, Hepples and Strouds sat downstairs in the two long seats that had been left empty, as if reserved for them. The early workers made for the stairs but were overtaken by a swarm of children and ended up scattered miserably among them. The three girls, all wanting to smoke, went upstairs too. Julie Lacey cleared a gaggle of younger boys off the front seats with a look.

Tom Hepple had sat up all night, his legs stretched out beyond the end of the child’s bed, his face caught in the mirror on the dressing table opposite him. The quilted nylon cover crackled beneath him. He kept his gaze fixed on his reflection but at the edges of his vision, the rosebuds on the wallpaper throbbed. Above the mirror were shiny posters of musicians and footballers, all eyes and teeth. He had not let Christie turn off the light.

Tom grew tired and could guard against his body no longer. His feet jerked and the fingers of his right hand began to tap rapidly on the bedside table. He became aware of the same acrid breath going in and out of his lungs, getting smaller each time he inhaled. His hand gripped the spindly table which tipped, its contents slipping to the floor: a china shepherdess, an etched glass, a plastic snowstorm and a bowl of sequins. Tom got down on his hands and knees. Nothing was broken, but the sequins embedded themselves in the thick strands of the carpet and were too small anyway for his fingers; the shepherdess’s head came away in his hands. Tom’s chest tightened, his stomach churned and he felt the pressure of his panic and knew that any minute he would lose control. He rushed into the hall where identical doors carried flowery ceramic plaques: ‘Mum and Dad’, ‘Darren and Sean’ and ‘Bathroom’. There was one behind him, too, ‘June’. Tom crept into the bathroom. He tried not to make a mess but he was shaky and all wrong. He rubbed at the wet carpet till the tissue disintegrated and stuck to it.

‘Carpet in the bathroom. What would Ma have thought?’ Christie stood in the doorway. He lifted Tom to his feet, took the tissue from his hand and threw it away. ‘Have a wash and come down. You’ll not know where you are yet.’

In the kitchen, Sophie was filling a kettle. She wrenched the tap on so strongly, water sprayed up over her hands. She banged the kettle down on the hob and tried to strike a match, but it snapped.

‘June off to school already?’ Christie did not meet her eye.

‘Couldn’t wait, I reckon. Good job the boys are still over at Mum’s.’ Sophie snapped two more matches. ‘He’s no better, is he?’ she continued. ‘He should’ve stayed where they know … how he is and can help him.’

Christie approached and put his hands on her shoulders. She turned abruptly in his arms, ‘We never could help him, could we?’

He looked into her broad face and saw that its softness had been exhausted. Tom appeared in the doorway. He was trying to smile. Sophie looked past her husband at his brother, the crazy twin who fluttered in and out of their lives, coming close like a moth that must be caught and put out of the window. They would try to hold him and free him but he would flap out of reach, terrified and bruised by any such contact. Then he would be back, circling them again.

Sophie gestured to a chair but Tom hovered, uncertain. Her white kitchen and bleached hair dazzled him. She put a mug of tea in front of him. ‘It’ll have to be black. The milk turned on the step.’ His electricity had once seemed like a kind of wild static that confused everything nearby. After ten years of hospitals and halfway houses, he was still jittery but his eyes were dull.

‘I’ll go up for more,’ Tom gabbled, thinking he wanted to help and that he wanted to get away. Sophie watched him through the window. She didn’t want him here and above all, she didn’t like to be reminded that it was because of Tom that she had married Christie. Sophie had met Tom first because he had been at the Grammar while she was at the High, before the two schools were amalgamated. Tom had been beautiful and clever, and she had taken his trouble for sensitivity and his agitation for great thoughts. She hadn’t had to get too close before realising that he was a very bad idea – and then there had been Christie. Tom was so away in his head that he’d barely seemed to notice that something was happening between them and then that it had changed. She’d felt such a fool.

You do not have what it takes to be in this world, she thought. You are a monster.

The bus driver, wanting to be gone from the village before Mim got loose, revved his engine but stopped again as Mrs Kettle yanked the cord above her head, ringing the bell repeatedly. ‘Edna isn’t here yet! She’s had to collect her dressings.’ A minute or two passed as Edna Lacey limped towards the bus stop. She stood there, smiling, and didn’t get on. The bus conductor, a weak-minded, yellow-haired boy whose mother was a Stroud, hesitated and looked to Mrs Kettle, who thought for a moment, then called out, ‘Are there more to come, Edna?’

Edna Lacey peered up and down the High Street. ‘Can’t say as anyone’s on the way.’ She kept looking down the road and made no move to get on.

‘Shall we be off?’ Mrs Kettle asked no one in particular and no one felt it their place to reply.

A Triumph came puttering round the bend. Edna Lacey stepped into the road and raised an arm. The car stopped and as Father Barclay got out to see what she wanted, Edna Lacey opened the passenger door and got in. There were three more villagers in the back of the car already.

Father Barclay stood for a moment between the car and the bus. He smiled and shook his head, as if rehearsing something in a mirror. He rocked on his heels, swung his arms and clapped his hands. Then he laughed his high, rapid laugh, which began as a bird call and ended as gunshot.

‘Don’t let me keep you!’ he boomed to the conductor who was standing on the platform, watching him. ‘I’ll bring up the rear!’

The only people in the village whose petrol wasn’t rationed were the two priests, the doctor and Constable Belcher. They never travelled far without being hailed for a lift.

The conductor’s face was expressionless and remained so as Mrs Kettle rang the bell three times on his behalf, the signal that they could set off. The driver waited as Father Swann glided by in his Jaguar, which was also full. He started up the engine and accelerated hard, just as Tom Hepple stepped into the road, stopped in the middle and put down the pint of milk he was carrying. Although Tom kept moving, the driver was confused by the bottle. He braked late and sharp.

The Kettles, Hepples and Strouds fell sideways against one another heavily but silently. They were too old to be startled and make a noise about it at the same time. The early workers gave hoarse grunts or sighs, perhaps the first sounds of their day. The children shrieked and then immediately began laughing at those whose books had slid from their satchels or whose apples had rolled across the floor to be kicked by whoever could reach them.

Tom had been walking slowly so as not to be back in Sophie’s kitchen too soon. And then there was the bus, the one that he had caught from up by Temple Grove, going to school each day. It was waiting. He didn’t have to return to the new road off Back Lane, Stevas Close or whatever it was called, and Christie’s hard new house. He could go home, but the milk? He could leave it here. They would come to find him and there it would be. The bus was crowded. I know everyone he thought, there is my grandmother only she’s dead. He got upstairs quickly and saw all the children, boys that were him and Christie, girls that were Sophie. He walked along the aisle as whispered explanations rippled past him. There were three girls across the front seats and the one on her own in the corner, not turning round, he knew, was her.

‘Mary George.’ He tried hard to say her name softly, but his voice caught and blurted it.

Someone laughed fast and then sucked in their breath. It was quiet for what seemed like a long time and then the conductor was tapping Tom Hepple on the shoulder. ‘There’s no standing on top, sir, come down, take a seat and we’ll be off.’

Tom ignored him. ‘If you could show me again, while the water is falling …’ Mary had shut her eyes. Julie Lacey was staring at her, not at Tom Hepple like everyone else.

Tom could see the girl was shaking, her back was hunched over and her shoulders raised. He didn’t want to frighten her; he must try to explain. ‘You were just a child, I know that, but it was your father …’ Why should she be afraid? ‘Your father could come back …’

June Hepple stood. Since the end of childhood, she had moved like someone in heavy clothes underwater, what little she said floating up in small bubbles from her uncertain mouth, and even though she still could not meet her uncle’s eye, for once June did not look to Julie Lacey for her cue. ‘I’ll take you back now, Uncle Tom. You don’t want to be going anywhere.’

June took his arm and her hand was his mother’s hand, and he felt the world settle into place. She led Tom downstairs. The conductor handed her the pint of milk. Things were ordinary and clear again and Tom could see the children were not him and Christie but what might be their children, and that the old woman looking hard at her folded hands was not his grandmother but his mother’s sister, an aged Aunt May. He tried to greet her but she did not look up. June pulled him gently towards the pavement, ‘May’s deaf sometimes, Uncle Tom. Remember?’

Five minutes silence was all Julie Lacey could manage before she began shifting from side to side, peeling her bare thighs and the damp nylon of her waitress’s uniform from the plastic trim of the seat. She tutted and puffed, and fanned herself with one hand. Mary ignored her. ‘June’ll have to watch her uncle don’t chop her up into little pieces one night! Mind you, he’s not half bad looking, for a loony I mean, if you like that sort of thing.’ She guffawed but Mary only turned her head further towards the window and those children sitting near enough to hear her gasped, not understanding that this was more or less a joke. ‘You’re going to have to be careful too, Mary George … says those Hepples never did forgive your father …’

Mary pulled a tobacco pouch and papers from her bag. She slowly teased out the tobacco, laid it on the paper, creased the edge with her nails and rolled her cigarette. She ran the tip of her tongue along the glued edge and sealed it. Her hands did not shake. Julie had noticed that the children around her were listening eagerly now. ‘Must have felt bad in the end … couldn’t face anyone in the end, could he? Face you, does he?’ Mary lit her roll-up and closed her eyes.

Julie didn’t speak again before she got off at the roundabout on the edge of town. Since leaving school a year before, she had worked at the Amber Grill, the restaurant in the Malibu Motel, built on the site of Barry Spence’s old transport café. The eldest Spence brother, Barry had made a deal so mysterious and successful that his greasy spoon with its unofficial bunkhouse was swept away overnight and replaced by a stucco-fronted restaurant with a reception area, and a string of pebble-dashed motel rooms. He had a tarmacked car park and a sign with neon palm trees at the entrance to his own sliproad. It was said that Barry’s success was due to secrets. The old Amber Café had been a traditional meeting place for those with unofficial business, who thought they would be alone among travellers and strangers. With a sharp eye and careful organisation, Barry had averted many unfortunate meetings. There were councillors, property developers, lawyers, builders and bankers, husbands and wives who were grateful to him.

Barry loved the constant stream of one-night visitors, the late-night traffic turning off the London road, bringing in people who travelled for a living and saw the world. He thought of England as a wide open space, criss-crossed by endless motorways and punctuated by places like the Malibu Motel. He thought of America. Barry mugged up on cocktails, turned the Amber Grill into an American diner and hired burly blondes like Julie Lacey to serve hamburgers topped with pineapple rings to salesmen and lorry-drivers who wanted bacon and eggs instead.

The sixth-form common room of Camptown High was the last in a row of prefabs that no one had ever pretended would be temporary. The pupils were allowed a kettle, a record player and to wear their own clothes. Smoking, although against the rules, was tolerated as long as it was unseen. For this reason, the windows were kept shut and the blinds drawn. There were a dozen low armchairs, arranged in three groups, and a row of desks that were empty and unused. The walls around each group of chairs were covered in posters: psychedelic, sporting and political. Billy was asleep, stretched across two chairs beneath a lurid album cover of chasms and goblins.

Mary walked over and parted the long hair that covered his face. ‘Where were you this morning?’

He stretched and sat up, not smiling. ‘And where were you on Saturday morning?’

Mary sighed. ‘I went home.’

‘Without me.’

‘You had already gone!’

‘I got the last train, like we’d planned to.’

‘You didn’t say goodbye.’

‘You were busy.’

Mary stood up, her fists clenched. She and Billy had gone to the party in Crouchness together. She didn’t remember seeing much of him there, or noticing when he left.

Billy fiddled with the beads round his neck. ‘I slept out last night and walked it.’

‘The state of your feet. You’re turning into a satyr!’

Billy smiled and flexed his toes. ‘Perhaps I am at that.’ He hadn’t worn shoes for weeks and carried a pair of flip-flops to put on if a teacher approached.

‘And you stink of patchouli oil, Billy.’

‘And fresh air …’

‘Not even fresh air smells of fresh air any more.’ Mary had been in the room for five minutes and its atmosphere, soupy and stagnant, was making her sleepy as well. She curled up in another chair and closed her eyes.

When Mary’s father, the architect Matthew George, decided to go into partnership with the builder Christie Hepple, undertaking local conversions, he bought the old chapel.

The Chapel had been converted from a grain store by the local Baptists. They had replaced the roof, laid a stone floor, and whitewashed the brick and beams. Then their minister, the Reverend Simon Touch, had inherited a gloomy house on the High Street and had built a new chapel in its cavernous basement, complete with an immersion pool. Mary had once gone back there after school with his daughter Hilary, who had promised that she could dip her fingers in the tank. Hilary said people fell into it backwards for God ‘so the water runs up their noses.’ The water in the murky tank looked quite solid and Mary had wondered how anyone managed to sink into it. Whose hands helped them and how did they surface again?

The Baptists had put in a window above their altar, a large triangle of plain glass flush with the roof, under which Matthew worked on a raised platform he’d built along the centre of the building. There were rough stairs at the far end. Mary had liked to creep up and tiptoe along the aisle between the shelves of books, files and papers, like a library she said, to the end where the platform broadened to the width of the Chapel, level with the foot of the window, and Matthew sat perched on his spindly, rotating stool at his slanted drawing board, pencilling in tiny elegant numerals and angles. Mary would stand behind him at the window, recording her height on each visit by breathing on the glass.

On the ground floor, Christie had kept his tools and machinery. He also had a desk, a trestle table, pushed against one of the small windows that were shuttered and set deep in the wall. Mary would walk solemnly across this space, holding herself straight but looking quickly from side to side at all the sharp edges, the twists, spirals, points and planes.

Christie let Tom go in ahead of him. ‘Don’t be troubled if it’s not right.’ Even though light pushed through the windows, the interior of the Chapel was cool. Tom set down his rucksack and considered the swept floor, bare shelves, trestle table and stool. ‘Simple,’ he smiled.

‘It is that.’ Christie bustled past him to the back where there was a sink, cupboards and a Baby Belling two-ring cooker. Matthew had installed all this. He had stayed overnight there sometimes, more so towards the end, locking the door against Stella, whom Christie had found one morning, half asleep on the grass outside.

‘Cup of tea?’ Christie was busy unpacking carrier bags and filling the cupboards with tins of soup, beans and spaghetti; packets of biscuits, sugar, custard powder, dried milk and instant mash; bottles of tomato ketchup, malt vinegar and HP Sauce. Tom had hardly eaten anything, hardly slept either, in the two weeks that he’d been back. ‘I’ll come again first thing. You’re to sort out your benefit at the Post Office and I’ll fetch some more groceries.’ He took as long as he could to put things away, watching over the kettle as it boiled and then leaving the tea to brew till it was bitter and lukewarm, and the granules of dried milk floated greasily on its surface. He waited till Tom was nearby before handing him his mug, almost without turning round.

Tom carried his mug and rucksack carefully up the open staircase to where Christie had made up a mattress under the big window. Not having any curtains that would fit, he had taped blue sugar-paper over the glass. For Tom, this marine light made the place even cooler. By laying out his clothes, books, papers, pens and shoes across the floor and along the nearest shelves, he created a rectangle the same size as the space he had lived in on the hospital ward, the same as half the room he’d later shared in the hostel – four by eight paces. June’s room had been the wrong shape.

Christie understood that Tom needed to be somewhere familiar. He couldn’t be at ease in the new house but needed to be in the village. The Chapel was ideal, almost off on its own, nearer than anywhere else to the Dip, but not within sight of the water. Since Matthew had left, Christie had worked for people who had their own offices and drew up their own plans. He hadn’t needed the Chapel for anything more than a store. It only took a morning to sort out his tools and paints, transfer them to his garden shed and clean up the outhouse.

There was a filing cabinet of paperwork Matthew had left: old contracts and invoices for barn conversions, extensions and conservatories; rejected designs in concrete and glass for Havilton New Town; the chalet design they had worked on together for the holiday camp at Crouchness. Christie had also found some of the pamphlets Matthew had designed for Stella’s business: beige card printed with droopy chocolate-brown art nouveau script and edged with flowers. She had begun dealing in Victoriana when she came to clear out her parents’ home and decided to get rid of the dark, glossy, intricate clutter she had always hated. In doing so, she had discovered a market among London dealers for lace antimacassars, cameo brooches, fur tippets, kid gloves, jet beads, fish knives and sherry glasses.

When Matthew’s great-aunt Alice Spence died in the house she’d lived in for sixty years, Stella made her sons an offer. From there, she’d gone to auctions, placed small ads in local papers and people had just got in touch. She expanded into forged ironwork that was made to order by the son of Allnorthover’s last blacksmith, as the leaflet said – weathervanes, firescreens and flower-pot stands. When the dairy in the High Street closed down, Stella leased the premises and opened her shop, Hindsight, scrubbing out the abandoned churns and standing them by the door full of corn sheaves and dried flowers. The churns were still there, and now people kept trying to buy them. These days Stella was selling jazzy Twenties ceramics, framed prints of adverts from the Thirties and Forties, and enamelware.

Tom came down, tracing the wiring that was tacked along the side of the stairs. He followed it across the wall to the fusebox and from there to the clutch of switches by the door. He went over to the kitchen and pulled each plug from its socket, for the cooker, the kettle and the toaster, and put them back in again.

‘I’ve brought you something to keep you busy.’ Christie waved an arm at a heavy old wireless. ‘You were the only person that could make that cantankerous old thing behave, so I kept it for you.’ Tom knelt beside the wireless and ran his hand over the blistered veneer and the dusty cloth that covered the speaker – tiny red and cream diamonds, like material for a dress. The dials had yellowed and their grooves were worn smooth. ‘I kept this, too,’ Christie reached into one of the carrier bags and handed Tom a battered tin box. Tom opened it and began sorting through his tools. They were intensely familiar. Either he had always remembered the exact shade of blue paint and the shapes in which it had worn off the wooden handles of his pliers and screwdrivers, or they were reminding him of their long existence. The soldering iron weighed exactly in his hand, the cold heavy handle, the hard dullness of its colour, the bitter smell. Solder, fuses, batteries, bulbs and coils of copper wire all impressed themselves upon him, giving the pleasure of something not thought about for years, and then entirely and vividly remembered.

‘How … therapeutic.’ It was the first joke Tom had made since coming home.

‘You’ll be wanting hospital food next!’ Christie laughed, encouraged now and sure that his decision to keep Tom close by, to help him set up alone, was right. He was safe in the village, where everyone knew him, and near enough to the water to have to accept it in the end. Christie had explained this to Stella. She was concerned for her daughter but the girl had just got caught up in Tom’s grieving.

Even alone in an old building he’d always known, Tom couldn’t sleep. He got up, unplugged everything, plugged it all in again, opened the back of the wireless and then, looking at its circuitry, felt tired and went to lie down. The thing had leaked memories of times when it had been his head that had buzzed and crackled, as if badly tuned, when it had picked up what appeared to be fragments of different stations: a woman singing a single verse of a song over and over; the Morse Code SOS of a sinking ship; a man repeating the same joke: ‘What did the mouse say when it saw a bat? Look, an angel!’; the thin, high endless laugh of someone who was exhausted and wanted to stop. His mother had held his head and stroked it in long lines till the noises were gone. She’d called it ‘ironing out’.

When Christie let himself into the Chapel the next morning, he found Tom lying on the mattress. He was shaking so badly, he couldn’t speak. Christie helped him down the stairs and walked him the few hundred yards along the High Street to where Dr Clough was just opening up for the Saturday morning emergency surgery. There were half a dozen people waiting already and they filed into the tiny waiting room where Betty Burgess, the old doctor’s wife who still acted as receptionist, took their names. The wooden chairs ranged around all four walls of the room were filled by those waiting. The room was so small that those opposite one another were almost knee to knee. When Dr Clough called Tom’s name first, nobody objected.

Half an hour later, the doctor appeared in the waiting room without Tom and asked Christie to step outside. ‘I don’t have his complete records yet, only a note of what he’s supposed to be taking. Why did the hostel let him go?’

‘It was up to him, wasn’t it?’

Dr Clough was an elegant figure with a cool manner and hollow good looks. He had arrived in Allnorthover a few months earlier and was already known as Dr Kill Off.

‘He just needs his pills, Doctor. He forgot to bring any back. They always did stop his shakes and help him sleep.’ Christie couldn’t have a brother of his going back into the bin, not again. ‘We can manage.’

Dr Clough’s face was expressionless. ‘He can have his pills, but you are to see that he takes them and I won’t give him enough of anything to hurt himself. He shouldn’t stay alone for the next week. I want to see him here on Monday morning to discuss further treatment. You must be glad that your brother’s home, Mr Hepple, but that doesn’t mean it’s the best place for him.’

Christie flushed, shocked at the doctor’s bluntness. Old Doctor Burgess had made every exchange seem like a chat over tea. He had asked after the family, even the dog, and had never said Tom was anything more than ‘over excited’ while suggesting pills might help as offhandedly as if they were vitamins. And he’d got Tom the best specialist help: an expert in Camptown. When Dr Burgess retired and the surgery moved from his front room to the old coach house, he had put forward Christie for the conversion. It seemed strange that such a man had recommended this new doctor but then again, once he’d retired, Dr Burgess had all but withdrawn from village life, resigning from the Parish Council, threatening not to run his bottle stall at the Fête and barely stopping to greet people in the street. Betty was working out her notice. There was talk of a new life: a boat or a caravan.

Christie followed Dr Clough back inside to wait with Tom while the doctor unlocked a cupboard in his dispensary and poured two different types of parti-coloured capsules, brown and blue, red and white, through his pill-counter. He scooped them into glass bottles and wrote detailed labels.

‘Two of these each morning and two of the others at night. It’s all written on the labels but it might help to, I don’t know, think “red and white: night” or something like that, to remember.’ Christie was taken aback. Red sky at night, thought Tom, shepherd’s delight.

The doctor continued. ‘They’ll take some days to really help and in the meantime you’ll feel pretty awful, but try to remember that what you’re feeling will pass. Go back and stay with your brother for a bit. Call me anytime.’ The doctor held out the bottles to Tom who took them and passed them to Christie, who tried to hand them back.

Camptown had always been a provisional sort of place. It benefited from leading elsewhere, accumulating, by chance, all the historical features expected of an English town. Its name had an ancient derivation from its role as a Roman staging post, half-way between the capital and the more useful and significant Camulodunum on the coast to the north. By the thirteenth century it had acquired a city wall, not as a place worth protecting in itself but as part of the frontline against the Danes. The small, orderly grid of Roman streets had been consolidated and extended. As the roads improved, more traffic passed through on its way between London and the coast. These journeyings back and forth rubbed against the town and created a kind of static through which people got stuck. The railway threw out an arm towards it. Manufacturers and merchants trading in wool, wheat, salt and corn settled on the outskirts, building substantial villas and funding civic works. Camptown broadened and put on weight without gaining character.

Remnants from each era could still be found, leaking through bland new surfaces. The hillock that lay just beyond the fence of the High School’s playing fields was a prehistoric burial mound, hemmed in by housing estates. A Roman villa had been excavated by the river and fragments of its concrete (mixed from stone and lime) and its tesserae had found their way to the British Museum, along with the skeleton of a baby thought to have been a foundation offering to household gods. Newling Hall, the mansion that now housed the art gallery and museum, had a fine Jacobean staircase, carved in the Spanish style. It was regularly hired by film crews who spent days repeating a single scene: the sweeping exit of a woman in a trailing gown or the clanking descent of a cavalier. For safety reasons, the staircase was never polished between hirings. All other floors in the public parts of the building were covered in linoleum.

Holidaymakers sometimes turned off the bypass in search of tea or a bed and were glad of a few sights to make the extra miles worthwhile. There was the small medieval cathedral that made Camptown technically a city, now dwarfed by the new civic hall, for which the derelict Corn Exchange had been demolished. Nobody came to see the cathedral’s architecture although they would make a thorough tour of the building before seeking out the Sheela-na-Gig, one of the few examples to be found in East Anglia. Carved on a pillar in a shadowy corner to one side of the pews, her wildness, her voracious eyes and spurting breasts, her fingers opening her vagina wide between splayed legs were intended to shock parishioners out of temptation. Somehow, she did just this.

Camptown had been damaged by bombs that had missed either London’s docks or the coastal defences, or had been jettisoned. The gaps this left in the High Street had now been filled with large commercial premises. The old shop fronts with their ornate masonry, ironwork and curved glass made way for the flat frames of display windows. The town made room for municipal resources: a multi-storey car park, a library, a theatre, a swimming pool, a bus station, a new hospital. These efficient buildings were oddly cramped and dim inside, with small windows and fussy arrangements of interior walls. They cut across streets which would have been too small to contain them, creating odd alleyways and dead ends. People who’d lived in Camptown all their lives found themselves getting lost and going to the swimming pool to pay a parking fine because these civic façades were all so alike.

Camptown had become awkward and diminished. Its constant, incidental and half-hearted replanning made it a difficult place to wander about in but Mary and Billy, who often found themselves with time on their hands, could pass several hours doing just that.

A fortnight after Tom Hepple’s return was the last day of term. They left school at four and made their way through the ‘top end’ of Camptown, the point at which the High Street frayed into new roads leading to housing and industrial estates, and the multi-storey car park. Beyond this were the expensive Edwardian villas with broad curved drives, ivy and wisteria, and long gardens edged with old trees: chestnuts, magnolias and limes.

There was no shade in the street so they walked slowly and kept stopping. First at a corner shop that would sell them beer and then at the bus-station newsagent which was tiny and grim, but sold them tobacco and cigarette papers. They came to the park playground. The metal bars of the merry-go-round burned to the touch. A couple of toddlers playing listlessly in the sandpit were hauled away by their mother, and then Mary and Billy had the place to themselves. They kicked off their shoes and sat for a while with their feet in the sand, until Mary noticed all the crisp packets and baked dog turds.

The see-saw was in the shade so they lay down on either side of its central pivot, more or less balancing each other. Mary drank her beer quickly and drew hard on her cigarette. She gripped both tightly in her hands. Dreamy Billy flopped on the see-saw with one leg trailing to the ground, his long fair hair spread out behind him, his cheeks the same faint pink as his old t-shirt. His purple corduroy flares were just as faded and all in all, Billy looked bleached or at least most delicately tinted. A roll-up sat loosely between his thumb and forefinger. Mostly, he just let it burn. He had pushed his other thumb into the neck of a bottle of beer and let it dangle.

‘Valerie says Christie Hepple brought his brother into the Arms last night.’ Billy’s big sister worked behind the bar of the Hooper’s Arms on Allnorthover’s High Street. Billy pushed himself up onto his elbows, tipping the see-saw, raising Mary into his line of vision. ‘What is he to you, anyway?’