Читать книгу Picasso Blues - Lee Lamothe - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеThe cafeteria down the street was close enough to East Chinatown that it was empty except for the two grill men, the cashier, and two idle Mexican-looking bussers who looked for a horizon to jump when Ray Tate and road sergeant 667 walked in. The cashier and the workers wore white gauze masks and tilted away from customers so they wouldn’t have to share breath. Someone had put a sign in the window: NO MASK NO SERVICE. Someone had added, No Chineess Niether. Under that someone wrote Cracker Asshole. And, beneath that in a casual scrawl: Ahhh, Soooo solly, Chollie.

The cashier silently pointed to a plastic bottle of hand sanitizer mounted near the door and Ray Tate and the Road pumped at it.

The Road knew the counter crew and he armed two stale breakfasts off the hot table and drew two mugs of coffee. He brought the tray to the window booth. The eggs were poached to rubber; the brittle toast under them was barely tanned; the bacon was pale lank flesh. But the coffee was coffee and it was hot, and, Ray Tate knew, at seven in the morning after a bad night there was no such thing as crappy hot coffee.

“So, Ray,” the Road said, passing his notebook over for a scribble, “you like that mutt?” He made a toneless voice, “‘You mean, duh, how many times I jerked off, like so far this morning or all day yesterday too?’” He laughed. “Fu-king mutt.”

Tate signed his name and badge number and wrote the time under the Road’s last notation, then drew a wavy line to the bottom margin, looping to circle the page number.

“What brings you out to the streets so early, Ray? I thought you were up in Intelligence Zombies?”

Ray Tate had been out and about because he’d painted through the night until early in the morning and then couldn’t get to sleep with the whirling colours in his head and his ceiling fan indifferently shoving the humidity around his apartment. His morning assignment was to set up at the courthouse and monitor the release of a suspect on a homicide case. He’d gone on a cruise, riding the radio, killing time. When the Road voiced out for a scribbler, he’d snapped up the rover. With the bug gone wild and the chief’s decree that a detective or soft clothes had to attend every crime stage with a wisp of gun smoke, everybody had to lift a little extra weight. There were stages, especially in the Hauser North Projects, that had been frozen for more than twelve hours because no one in a suit or designer windbreaker was inclined to run up there, stick their head in, and scribble in somebody’s notebook.

“We should’ve probably taken him in, Road. If he goes south, we’re going to wear it like the slippery brown hat.”

“That guy, Ray, that guy looks after himself. You see his knucks? It looks like he got a few shots in. When we patted him down there was gun oil on his shirt, there, on his waist. He stank of gun smoke. I figure he had a heater of his own tucked away and he dumped it before we got there. Dumped his wallet, too.” The Road picked up a piece of toast and tried to stab the corner through the poached yellow deadeye. The bread snapped like a cracker. “What the fuck we going to do, anyway? Arrest the guy for getting shot?” He gave up on trying to penetrate the deadeye and crunched on the toast. “I asked him. I said, ‘Who shot you?’ Fucking guy’s worse than Bill Clinton. He said, ‘Well, it depends what you mean by shot.’” He started laughing.

Ray Tate kept his raid jacket on and zipped. The cafeteria was cold with air conditioning; it was believed that the bug multiplied in heat and humidity. The windows looked up the damp street at the broken crime stage. Four bulky men in surgical masks and sports windbreakers, wearing red baseball caps, headed in the direction of East Chinatown, carrying golf clubs. Volunteers. A one-man ghost car trailed them at a walking pace.

The fella was standing around in the brightening grey dawn, scoping The Road’s flashing cruiser and Ray Tate’s unmarked Taurus. Waiting, Ray Tate thought, to retrieve his gun and wallet from where he’d dumped them when he realized those sirens were singing for him. The fella had a fresh cigarette in his mouth and his right hand was pressing a medi-pak to his left shoulder. One-handed, he dragged on a recycling bin and sat down on it, leaning back against the brown bricks to hang in for the long haul. People shuffled past him, all wearing surgical masks, all moving quickly. They each seemed stiff, holding their breath. No one headed into the plagued precincts of East Chinatown.

Ray Tate, who fancied himself a bit of an artist, felt like he was sitting in a moody Edward Hopper painting, looking out at an old pearly photograph of hopeful ghetto life. “How many guys you down?”

“With the bug? Out of my twelve-guy night leg, there’s four left, plus me. I got three guys at Mercy, one of them on a lung. Timmy Harper. You know Timmy?”

Ray Tate nodded. When he’d come out of the departmental hearing that cleared him after he’d put down the second black guy, a television reporter said Congratulations, Ray, and handed him a lit cigar, trying to get footage of him looking like some arrogant gunner who’d got away with something, celebrating it off a cubano. Timmy Harper had grabbed the stogie and stabbed it at the guy, grinding the hot coal into his hairpiece. Timmy Harper lost a beat and went down to patrolman, getting badly stomped in the Racist Ray Tate riots. “Tell him I’m having a thought, right?”

“He’ll appreciate it.” The Road looked at the fella up the street, basking in the flashing blue and red lights. “Good that you’re getting out and about, Ray. So, how come, anyway, you’re out so bright and early, on the rover?”

“This fucking heat. With the bug and the Volunteers, here I be.” He rubbed his face. He had paint crusted on his fingernails. His hair was too long and greasy and he had an unshaped beatnik beard. He was going grey and his eyebrows seemed to be curling into his eyes. There was a benefit to the dripping hair: it obscured his missing earlobe, snicked off by a wild shot when he’d been gunned. His eyes were red from smoking out his apartment. Several gin and tap waters might have something to do with it. Under his raid jacket he wore a black leather biker vest with silver conches over a grey sweatshirt, black jeans, and scuffed short cowboy boots. The handle of his gun, riding in his boot, made a distinct bulge. His badge hung from a breakaway chain around his neck. “Yesterday they had me like this directing traffic down on the Eight while they untangled a wreck. One guy almost clipped me and I caught up to him in the gridlock and tinned him. ‘What the fuck’re you doing, man?’ He said: ‘You? A cop? Fuck, I thought you was gonna wipe my windshield. I lost so many wipers to those guys I got my own parking spot at Walmart.’ Duh.”

“What you do? You wallpaper him up?”

“Naw.” Ray Tate shrugged. “If I saw me, badge or no badge, standing the middle of the Eight looking like this, I’d speed-dial my lawyer, lock my elbows and floor it, brace for impact. Anyway, I went down to Stores and checked out the jacket. Enough’s enough.”

Up the street outside the window, a short blue-and-white van with a caduceus stencilled on the side stopped in front of the shooting victim sitting on his recycling bin. Someone had spray-painted balloons from the forked tongues of the twisted serpents of the caduceus and filled them with FOK YU in stylized Chinese characters. A brisk young black woman wearing a mask and a nurse’s habit climbed from the passenger seat with a handful of surgical masks dangling from her fingers. She stood at a good distance, speaking to the fella, then leaned and at arm’s length held out the masks.

The fella reluctantly took one and awkwardly tied it to his face. After the woman boarded the van and it slid away, the man stared after it for a moment, then removed the mask and used the point of his cigarette to singe a hole in it. He waved it in the air to stop the burn, then tied it back on and stuck the cigarette through the hole, exhaling jets of smoke through his nose.

“Road, I’m rolling. Thanks for breakfast.”

“No problem, Ray. Don’t breathe in.”

Ray Tate wanted a real breakfast even if he had to pay for it.

Prowling the streets, it was eerie still, seeing masked pedestrians and motorists making their way through the morning. The four big men in sports windbreakers and red ball caps sat on folding chairs at California Street, at the gates of Chinatown. Drivers had their windows up; cringing pedestrians avoided eye contact. A taxi driver sped by a well-dressed masked Chinese man waving him down with a rolled up newspaper; another taxi clipped by, wowing wide in the road. In the rear-view mirror, Ray Tate watched the Chinese man start the long hike up Harrison Hill, rhythmically slapping his newspaper against his pant leg in frustration. At a coffee shop an Asian woman in business attire, holding her briefcase against her chest, was blocked by a man in a white apron waving a spatula over his head, shouting, “We’re closed, we’re closed.” Behind him through the street-front window, Ray Tate could see the place was packed with hunched customers who lifted their masks to sip coffee or eat food.

Down at the waterfront where the river widened into the lake, there were dozens of boats bobbing off the city’s edge. People believed the bug was landlocked and those with sailboats or power monsters slept on them, barbecued meals on deck, had rifles or pistols at hand to repel the diseased. They kept an eye to the pennants on their masts, ready to weigh anchor and head for Canada if the wind changed. There was litter and beer bottles on the riverbank where vigilant groups of Volunteers had spent the nights, ready to go hand-to-hand with any boatloads of Chinese migrants trying to sneak in from Canada to steal the American dream.

He eased the Taurus down under the span bridge and across the access road, turning where it lifted at the waterfront. There was a bit of reluctant mist still locked in the hollows. The sun was screened behind fading fog that looked nuclear in the strengthening yolky light. The radio muttered and he sorted calls and warnings and requests with a casual inner ear. A fist fight at a bus stop; all free units to the airport for a protest over rumours Asians were being routed from Chicago; a call to shots-fired on Marlborough in Stonetown.

Everyone was getting a little goofy with the two- and three-shift days.

“Any unit near Bradford and Queen?”

“Scouter four solo unit, right there, dispatcher.”

“Report a naked male complainant covered in pythons. Possible mental incompetent. Ambo rolling.”

“Repeat, dispatch? Did you say …” The voice rose to soprano, “Py-py-py-py-thons?”

“Ten-four, four solo. Pythons.”

“Unable to respond, dispatch. I got ophidiophobia.”

“Sorry, four solo. I meant to say ... ah ... spiders?”

“Okay, then, dispatch. Through counselling I’ve overcome my chronic arachnophobia. I’m rolling solo.”

There were appreciative single clicks.

A disguised voice whispered: “All yoo-nits. Ray Tate’s on the road with a pencil.”

Ray Tate laughed. The Road.

“All yoo-nits,” the Road whispered. “Ray Tate’s looking to meet new friends. Call him up for an autograph.”

A serious youthful voice came over. “Sergeant Tate, come up on the air, please?”

A female charger, sounding like a breathy beauty queen: “Oh, Sergeant Tate? Ray? I’m in the Hauser North, building four, tenth floor, south end of hallway. I’m real lonely, honey, my puffy pal is no fun. Knock twice and let yourself in. Do come and sign me out and we’ll go part-tay …”

He ignored that call but was a little itched to take a run up there anyway, scope the thing out. She sounded fun, the kind of girl who could stand in human gases and be cute with a clothespin on her nose. Except for his ex-wife, who was a cop’s daughter, in his adult life he’d only slept with lady cops and a nurse who wanted to become one. Except for a woman from an art class he’d taken over in Chicago, he hadn’t dated in a year.

Another man’s voice: “We got one down in the gun smoke at Hauser South. Sergeant Tate, come up on the air.”

Another: “We got a gunfire stage on Branksome in Stonetown no victim. Sergeant Tate, come up.”

The transmissions broke with three fast clicks as Ray Tate pulled into the waterfront parking lot near an abandoned bacon stand. He cranked the volume.

A level, unpunctuated voice, fast: “Urban Squad Two solo request backup transport supervisor seven-seven Marlborough Road holding one solo at gunpoint one-eight-seven no outstanding no ambo required supervisor detective required roll the catering truck.”

A female voice came on. “You okay, U Deuce?”

Silence.

Four rapid responses: “Ghost ten rolling solo.” “Ghost four rolling lonely.” “Scout four wheelman stag on it.” “Scout sergeant one lonely.”

Ray Tate imagined the ghosters and scouts and prowl cars, wherever they were, turning and racing like iron filings toward the invisible pull of a violent magnet. There were a lot of lonelys, solo units, and stags on the road, wheelmen whose shotguns were down with the bug.

He unlocked the short shotgun racked under the dash and started a slow roll to the access road, sorting himself a fast route, leaning for his red Hello light in the passenger-side foot well.

A ghost car came over, the charger a melodious thespian. “Ghooooos-terrrr Ten on the stage, dispatch. One for the box, one for the bag, all secure, break off, units. Con-tinue the coroner’s catering truck, sil vous plais.”

“Ten four, ten. Thank you.”

“No, my dear, thank you for this opportunity to perform for you …” the stage voice giggled, “… and all the other little people.”

Appreciative single clicks.

Ray Tate listened a moment. When there was no further air, he rolled the Taurus back into the parking lot. He locked the shotgun rack, took off his raid jacket and got out, slipping his rover into his back pocket. He popped the trunk and took a sketchpad and some charcoal sticks from his briefcase, slammed the trunk and walked to the edge of the river and set up on a defaced bench under a parched tree. The gold buildings of Canada, across the way, were half lit-up by the struggling sun. The sails of the boats in the foreground were still in low dawn shadow, vague smudges. A moaning tanker eased like a relentless predator down the centre of the lake under a plume of screaming seagulls.

Gold buildings and trudging tankers weren’t going to do it for him. He’d had it with the lack of flesh.

He waited for inspiration, something to engage him. It wasn’t long in coming.

On a nearby sailboat a woman came above deck. She had long black hair twisted into a rope, wore a white bra and red shorts. She carried a bucket and looked around, then stripped off the bra and shorts. Balancing herself to the rhythm of the waves off the tanker, she bent over and dipped the bucket into the river and doused herself down with water. At the distance she looked undefined, a smear of light grey. Minimalist, of no detail, as though she’d already been sketched or painted.

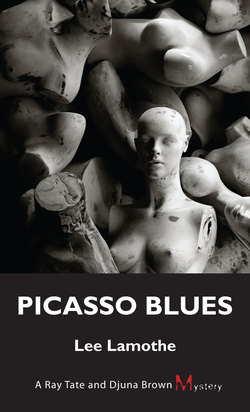

It was a vision that stirred him on a lot of levels. It was human and sexual, obscure and specific; enough to allow him possibilities, to fuck a little with reality. He flipped to a blank page and clutched the short charcoal stick between his knuckles. He kept the woman’s graceful shape but used the flat of the stick like a wide brush to make a perfect, small dark torso in graceful pose; he made her hair spiky, the hint of her eyes wide and Asian.

The voice of the female charger with the puffy friend at the Hauser North Projects rang in his inner ear. His homicide target was coming out of the courthouse at ten. He decided if the Hauser North stage hadn’t been broken up by the time the target was either down for the day or in handcuffs, he’d push the Taurus up that way, maybe get a date or at least a few laughs.

He finished the sketch and softly blew the charcoal dust off of the thick page. The shape of the small dark woman was a shadow, but he’d managed to get the idea of detail in there; she was recognizable. The buildings of Canada were bare suggestions of sinister mountains looming over her and the boat. The woman looked very small and isolated.

“Hey, Picasso, yo.”

He knew what the voice was. He kept his hands still and turned his head slowly and waited.

“You got a reason for being here, Pablo?” The man was red-headed and almost too short to be a cop and he was grossly out of shape, comically dressed as a jogger, smoking a small cigar. He wore an unzipped fanny pack and Ray Tate could see his hand rested on the butt of a revolver. “You want to break something out for me?”

Ray Tate smiled. “I just said that to a mutt, myself.” He identified himself as Intelligence and said he was heavy at the ankle.

The thick guy sat down and held his hand out. “Brian Comartin. Traffic. You got a better gig than me, the artist thing. They got me running up and down the Riverwalk, pissing in the weeds. Get us a boatload of Chinamen, they say, stop the invasion.”

Shaking his soaking hand, Ray Tate saw his face was flushed. “You okay, man?”

“I haven’t lifted more than a pencil in ten years and they come down to Traffic Flow and say, ‘Hey, you’re a cop again, get your fat ass down to the river, run around, and look for wet Chinamen. You see them, surround them, we’ll get you some backup in, oh, about two weeks when we get somebody off the lung.’” He laughed but he was panting and looked a little frightened for his own well-being. “Jeez fuck. If I wanted to work, I wouldn’a become a cop.”

“How many you guys down here?”

“Me and two others. One from Projections and one from Computer Enhancement. For four miles of Riverwalk, three miles of lakefront, and who knows what the fuck all in between.” He shook his head. “This fucking city. You ask me, every illegal who sneaks over here is a vote for the American way of life. When I first came on, I worked Chinatown, I seen them working the sweatshops, fifteen-hour days, buck an hour, kick back a quarter to the boss, rent a bed for a couple hours sleep. No fucking way do I send workingmen back in the water. I see a bunch of Chinamen coming up out of the river, man, I’ll take ’em home, give ’em a cash job painting my apartment.”

Ray Tate laughed and got up. “I gotta go to court.”

The fat man looked shy. He said, “Let’s see, what you did? You do anything good?” He was embarrassed. He looked at Ray Tate looking back at him with suspicion. “I, ah, I got a thing, too. I’m into, ah, poetry.”

Ray Tate thought for a moment, then flipped open the pad.

The thick man stared at the sketch. “Oh, okay. That’s good, man, that’s like art.” He looked around as though imparting a secret. “You should be in a gallery or something.”

“Yeah,” Ray Tate held out his hand. “I should be in Paris in a beret.”