Читать книгу Ray Tate and Djuna Brown Mysteries 3-Book Bundle - Lee Lamothe - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 21

ОглавлениеRay Tate and Djuna Brown decided to take advantage of the leeway the case had given them. They checked out a black Xterra and headed first to her place so she could pack a bag. He sat outside her leafy duplex and watched her go by the window, the inside lamps making a slim, flitting shadow. He felt like a schoolboy. When she came down she was wearing a bright khanga hat, a short, brown leather jacket, blue jeans, and had dumped her slippers for ankle boots and zany leggings. When she leaned to sling her bag into the back seat he made a show of checking out her butt. He saw the exposed tip of the barrel of her little automatic in its clamshell holster and her handcuff case.

In the four-by-four he drove the few blocks to his place. He told her she was looking like a hot beatnik chick and she gave him a smile.

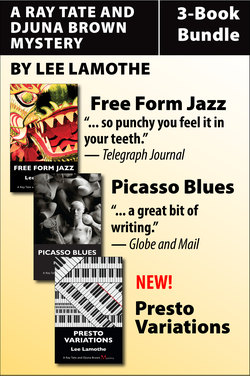

“You don’t know what you’re doing, do you, Ray? I bet you didn’t get laid a lot when you were younger. Right? This is all free-form jazz.”

“Free-form jazz?”

“Yep. You’re just hitting the notes and hoping you find a riff that makes sense. Smokehouse romance.” She put her hand on his leg. “I can tell you this: you maybe got a shot, Bongo, okay? Don’t work so hard.”

He sat back, pleased, and pulled into the driveway of his apartment building. Upstairs he realized all he had was his uniform in plastic and piles of bum clothing. He quickly tried on a pair of blue jeans but it had been months since he’d been exiled into the wilderness and stress and bugs had eroded him; the jeans sagged and gaped and he bound them with the second last hole on his belt. He found the union sweatshirts and windbreaker they’d given him at the sector and a threadbare sweater, and some socks and underwear and stuck them into a gym bag; he added the bottle of gin from under the sink. At the door he looked around at his pathetic pad. Since the second shooting his life, he realized, had been about free-form jazz. Unplanned. Undirected. Without discernable melody.

Before leaving he went into the washroom and found a package of condoms his freckly policewoman had left behind.

When he came out in his sagging Levis, Djuna Brown was behind the wheel, laughing. “Jesus, Ray, you look like a prisoner of war.”

She slid her handcuff case around onto her hip and slipped her clamshell holster off her spine and put it in the console. She belted up and made sure he did too.

Just north of the city she pulled into a huge Wal-Mart and Ray Tate went in to buy some pants and a jacket. She prowled through the glove compartment and when he came out of the Wally’s she held up a plastic card.

“Bingo, Bongo. An all-in credit card. This must be one of the Fed’s vehicles.” She wiggled her eyebrows. “With this, man, we can head all the way west, set up on the coast, and live the beatnik life. By the time the bills come in and they catch on, this fucker’ll be buffed flat.”

“First, Djun’, we have to torture Frankie, then take down Phil Harvey, the Captain, and the lab. Back up a shitload of pills into the skipper’s office. Then we have to make sure we didn’t make any mistakes. Then we either get fired or we get buried.” He stretched and yawned. “Except for all that, we’re on our way.”

She drove back onto the Interstate and made a bubble around herself, flicking her eyes to the rear- and side-view mirrors every minute or so. He dialed in a Chicago radio station and locked it in, then went looking for a Canadian lite-rock program he liked to listen to at night. He went back to the Chi-town station and caught some sweet Butterfield: “Baby I’m just driftin’ and driftin’, like a ship out on the sea …”

She eased over onto an exit ramp and left the Interstate. She seemed to know where she was going. There were little wooden signs pointing ahead, naming half a dozen towns. He saw Porterville had been defaced to read Por Ville.

“This your old turf, Djun’?”

“No. A little further north. Indian country. It gets very weird up there very fast, once you go couple of hours on. Lots of work, especially Saturday nights. But, you know, sometimes …”

“What?”

“Sometimes …” She clamped her mouth and wouldn’t let herself speak. Then she simply said, “Sometimes … not.” She thought of limp bodies hanging from trees like summer pods, of children huffing gasoline and dying with their faces crusted with vomit, of vicious domestic disputes fuelled by alcohol, and dead husbands and wives and lovers gutted like autumn deer.

But there were mornings, too, rumbling out of the mini-barracks in her huge Ford into a new sunrise, of doing walk-arounds and coming back to the truck to discover blanketed elders blowing smoke into the truck’s grill because they knew she was as different as they were from the white cops who patrolled their community like they were troops stationed in a foreign war of pacification. The smoke was for safety, someone said, a blessing. She thought about young men coming into the barracks office after making sure she was alone on shift and bringing haunches of venison and careful instructions for preparing it. Of massive trout wrapped in moss and newspapers, already gutted but with the head still attached. She taught the giggling girls about their periods, the shy boys about condoms. She had her dad put together a shipment of books and paints and sewing supplies and send them up.

She wanted to tell Ray Tate about all that and more. She wanted to tell him about how she got the dyke jacket and why she wore it. She said: “We’re here.”

* * *

Frank Chase lived in a leaning single-storey house just outside Porterville. A cannibalized old Harley was in pieces on the lawn. There were two fridges with the doors removed, laying flat on the patchy grass and a stove by the side of the house, behind them a stack of old wood and curly tails of barbed wire fencing. A sign with the silhouette of a revolver on it warned of dogs but suggested dealing with the dog was preferable to running into the owner. There was a Confederate flag tacked over the living room window.

“No F-250,” Ray Tate said. “Maybe nobody home.”

Djuna Brown rounded the street near the house. Through the rear window they could see a woman in a cloud of steam at a stove, the window cranked open in spite of the cold late afternoon. The woman had long, straight, jet-black hair and looked Native. She wore a plaid shirt and was beautiful, even at twenty yards. She seemed to be singing or speaking with someone. Periodically she reached out of sight and pinched up a thick joint, taking massive inhales.

They drove back around the front. Mindful of the dog warning, Ray Tate took his gun from his boot and put it into his jacket pocket. Djuna Brown removed hers from the console and clipped it behind her back. They weaved their way through the junk on the walk and the lawn onto the porch.

“How we going to do this, Ray? Cops or mutts?”

“Well, Djun’, how about free-form jazz?” He pounded on the door. “We’ll play it off her face.”

She was nervous. “Cool-ee-oh.”

To ease her, he said, “But if the dog answers the door, it’s every dyke for themself.”

She was smiling but stopped when the door opened. She saw the Native woman was a girl, seventeen maybe, and absolutely beautiful. She had bare, bruised legs beneath the plaid shirt that exposed hickies on her neck, and she had high cheekbones and placid features but her eyes were stoned and panicked. “Yes? What?” She looked at each of them. “What do you want?”

She looked like a victim. Ray Tate took his role. “Where’s that motherfucker?”

“Who? Hey, who are you?” She looked over their shoulders to see what they’d come in. “What do you want?”

“Frankie Frankie Frankie. Where the fuck’s Frankie?”

“He’s out someplace. I don’t know.”

“He was supposed to be someplace and he didn’t show up. So, where’s he? He in there?” Ray Tate called past her. “Frankie, you fuck, come out here, you fucking dootchbag.”

“Show up? He left yesterday. Down to the city, right? To do something with you guys?”

“With Harv. Harv’s pissed. If Harv has to come up here …”

Djuna Brown said, “You don’t want Harv making that trip.”

“Hey, no. Frankie left, said he was meeting Harv to do something. He was going to be back today but he’s not back yet.”

“If I have to fucking come in there …”

Djuna Brown told Ray Tate to calm down. “Take it easy, man. She doesn’t know. Guy’s fucked off and left her in his shit.” She asked the girl her name. “We have to find him, Sherry. We have to find him or Harv’s going on the warpath. Did Frankie take off in the truck? That beauty F-250, double cab?”

The girl nodded.

“Did he take his piece?”

She nodded. “I think so. He just said there was something heavy he had to do down in the city for Harv and some guys. That him and Harv would come back and drop Frankie off, then Harv was going to keep the truck to go up north. Harv was gonna return it tonight and me and Frankie were going down to the city to drop Harv off and Harv was going to stand us a night out.”

“North? Where north?”

She shrugged. “I dunno. Someplace, I guess.”

“Sherry, if we don’t find him, Harv’s gonna ask you where to find him instead.” Djuna Brown shook her head. “We don’t want that. We can get with Frankie and straighten it out, cool things with Harv. But we gotta find him, find Frankie. Where do you think this place is, north?”

“I dunno.” She thought. “A while ago, like last month, he had to go pick Harv up, up at Widow’s Corners, he said, take him down to the city. Harv needed a ride.”

Ray Tate said, “Widow’s what?”

“I know where it is,” Djuna Brown said. “Indian country.”

* * *

There was a Motel High halfway up to Widow’s Corners. Djuna Brown knew it. “Clean enough. No satellite, though. No pool. They’ll take the government card.”

“Yeah. We should stop and get a couple of rooms.” Ray Tate hoped the innocence on his face didn’t look too phony. “Rest up and poke around tomorrow.”

She smiled. “Sounds okay, Ray. There’s a bar attached to the place. I might go get myself some dinner and company for the night.”

“Yeah. Good idea. Me too.”

She stretched her arms up against the headliner of the four-by-four and groaned. “I need me a good old skinny white boy.” She put her hand on his leg. “I hope they still got the vibrating beds at the High.”

* * *

They put it off until after they’d had hamburgers and beer in the diner attached to the Motel High. She caught him giving her long looks then snickering as he looked away. She felt her own magic and amused herself when he was discussing tracking down Phil Harvey by making little movements of her mouth or lifting her eyebrows and breaking his chain of thought. It had been a long time since she’d played with anyone, since anyone had played with her.

For his part Ray Tate had butterflies. He’d forgotten how to introduce the idea of condoms on the first date but was glad he’d brought them. Like a lot of cops, when he was younger he’d talked a good game. But except for his wife and a couple of young women before her and one freckled policewoman afterwards, he found making a move had become antique to him. There were a few cops he knew who were hard-hearted motherfuckers, but most of them had soul, had a weird kind of romanticism that was always being thwarted.

The diner was ramshackle and neon bright and there was a constant ping of microwave ovens going off through the serving window to the kitchen. The hamburgers were shaped too perfectly to be handmade, the buns were steamed from frozen, the French fries were uniform and limp. Behind the counter a short-order cook knew every driver and customer who came in. He’d stared at Djuna Brown in her khanga hat but before he could say anything, Ray Tate had badged him and taken him aside to show him the photo of Phil Harvey.

“This guy, you seen him?”

“What kind of cops are you guys?”

“Not Staties or Feds, so don’t worry about it.”

The man studied the picture. “Yeah. Scarred up guy, right. It don’t show in this picture as bad as it is, but yeah he’s been in a couple times.”

“You know where he hangs out?”

The cook shook his head. “Nope. Wears a big fucking black leather coat. Came in, I guess, a month or so ago, first time I noticed him. Guy came and got him and they left.”

“The other times?”

“Well, you ain’t far behind him. Him and a blond guy came in today. Had a meal, like at noon, and left.”

“You see what they left in?”

“Nope. They was here, they was gone. Just like all of us, eh?”

“I guess. What about the other time, a month ago. You see what he left in?”

“Don’t recall. Dropped off first by an old geezer in a old, rusted beater. A pickup, I think. Grey?”

“You know the geezer?”

The cook looked around. “Well …”

“Hey, look. I don’t care about you or the geezer, whatever he is to you. I just want to catch up to this guy, see who’s who in the zoo.” He waited. “This is city work not state work, okay?”

“Geezer’s name is Paul. He’s got a problem, you know?” The cook touched the inside of his elbow. “He babysits a place up north a ways. Dunno where. There’s a lot of these old guys, old poachers, dudes from the city give ’em work.” The cook looked around. “Maybe something to do with drugs?”

“You think?” Ray Tate put a business card on the counter. “You see him again you call this number, okay? Maybe, if you get into the shit, you get a pass.”

He sat with Djuna Brown and told her what the cook had said.

A group of Indians came to the door and the short-order cook intercepted them with a baseball bat. He glanced at Ray Tate and Djuna Brown. The Indians looked. They stood outside shouting at the diner but eventually trudged off toward town in their thin denim jackets and construction boots. It was cold with a slow but steady wind down from Canada, feeling towards early winter, and they huddled closely together as they vanished in the darkness. Ray Tate thought they looked like a lost tribe and decided probably they were.

Djuna Brown watched them through the window. “Somebody’s got a lot to answer for in places like this, Ray. From here on up there’s nothing but this shit, these greed-head fucking Christians. Pray on Sunday, sell moonshine to the Indians the rest of the time.” She poured some beer into their glasses from the pitcher. “When I first came up, after training, they thought I’d last a week, maybe a month. Then they’d pour me out of the Spout. But the longer I stayed the more I liked it. I came to love it, like you love your little pieces of the city.”

He didn’t want to wait any longer before heading to their room. He didn’t want her to be in a sad place, a place that might thwart what he had in mind for them. But he realized he didn’t know much about her and hoped there were things he’d come to know, things she’d come to know about him. He realized he was thinking about his future, hers too, and that gave him the weightlessness of a revelation. She was only talking because he hadn’t asked. He’d talk about his dead black men but never if she asked him.

Djuna Brown heard herself, heard the tone of her voice. “Fuck it, Ray. This is our first date, right? You don’t want to know.”

“Sure,” he lied. “Sure I do.”

“Ray, lemme ask you one. All things being equal, which of course they’re not, what would you rather do? Go to the room and jam our brains out, or sit here and listen to me mope.”

“Well, Djun’,” he said. “Both.”

“But first?”

“I’ll get the cheque.”

* * *

At the beginning, when he started to make his way down her body, she said, “Ray, you don’t have to do that, you know. I told you I’m not a dyke, right?”

He stopped, looked up, and spoke with careful and serious enunciation. “Well, I believe you said you didn’t say you were. Not the same thing. I can check my notebook if you want me to give sworn testimony.”

He listened to her laughing and carried on. Inside he felt huge and complete and artistic, and full of laughter and something else. He thought of his wife, after the second shooting, after she found demonstrators in front of their split. Ray? Ray? You’re not a racist, are you? She was a cop’s daughter and her dad had never unholstered his gun, except for cleaning and duty inspection. He thought of the skipper and his hatred of Djuna Brown but realized it was simply a connection to the worst part of his life, a dead child in a garage. Djuna Brown had unknowingly revealed the moment when the skipper’s soul exposed itself and he was embarrassed by it. Ray Tate thought of the story Djuna Brown hadn’t talked about but everyone had heard: after she beat the teeth out of her moronic partner she’d been ambushed by the roadside and found naked by a passing motorist. The legs of her uniform pants tied at the ankles and a bratwurst sausage glued into her freshly shaven crotch. Someone brought the battery-operated razor, someone brought the glue, someone brought the sausage. Who else but cops? The very best people in the world and the very worst. She should have shied away from ever wanting to be one of them but she hadn’t and now she was here under his face.

She made a sound. He thought of a joke he’d once heard: how to do know when you’ve gone to bed with a lesbian? When you wake up in the morning you’ve still got a hard-on and your face is glazed like a doughnut.

He lifted his face to tell her that one. She grunted in urgent frustration and forced him down. His head was in a muscular vice of the cinnamon and the salty and he realized he was happy, felt that until now he’d walked a journey planned in advance for him from foster homes to high school to police college to uniform to plainclothes and back to uniform where he ended up with his Glock in his hand, standing over freshly dead black men. No one said: mix paints and slap them on canvas, dream about Paris, go down on a black chick, and when you’ve done all that you’ll be … What?

She began shuddering and whooping and then went boneless and he realized she’d been as without as he had. She patted his head like a boy when she was done. “Ray Tate, the king of swing. Jazzy Ray.”

“Well,” he said modestly, moving back up her body. “It has been said I blow a cool axe.”

* * *

After midnight, when she was in the shower, he took the gin from his bag and realized he’d forgotten to get mix. Wrapped in a towel he went barefoot out onto the icy motel landing and looked for a dispenser machine or at least an ice bucket. The machine was wrecked, there was no ice. He saw a group of Indians clutching bottles leaving from the back of the diner, the cook counting a wad of money.

He made gin and taps in plastic cups and carried them to the sagging bed. She came out of the washroom wrapped in a towel. They stretched out. She sprawled on top of him, weightless, he thought.

She began talking, her voice sometimes muffled, facing away from his face, her head on his chest.

* * *

She’d been one of only four minorities at the academy. The others were a dour heavy black woman and two Native ladies who looked almost identical. She was the smallest of them all and took some pretty good beatings on the self-defence mat. Often she found herself paired against the largest man, then the largest woman, the black one, then both of them together. There was a sexual aspect to the grappling, particularly with the black woman who loved to get her into a body scissors while overpowering her head with her breasts. Throughout her training she ached and nursed bruises; she had twisted fingers from small Japanese come-alongs and shooting pains in her elbows and shoulders from the takedowns. She had hickeys on her neck from the sport of the larger men who could apply them thoroughly in the ten seconds it took to legally pin her down. But none of it bothered her; she deflected the interest of the woman and the men with humour.

“I knew it was going to be rough,” she told Ray Tate, entwining their legs. “My dad drove a taxi nights in the capital and he saw cops all the time taking people down. When I told him I was going to apply he said I was too small. He wanted me to be a secretary like my sister or a nurse like my mum. When I told him I was giving it a try anyway he sent me to a self-defence school, twice a week for a year while I waited to get evaluated. Mostly what I learned was that you get up fast, afterwards, even if you lose. You look around for somebody else to get into it with. Even if you lose, my dad always said, make sure you’re not the only one going to Emergency.

“Anyway, the physical stuff wasn’t the problem. The problem wasn’t even the guys, at first. There was one guy who just wanted me. He was a nice young guy, farm boy from up Stanton way; he just locked onto me. Hangdog stuff. Little notes in my textbooks, helping me up after we grappled on the mat, invites out for drinks. I wasn’t too attentive to how I handled him. So one night when he asked me out for beers, near the end there, on a weekend, I said I couldn’t, that I had a date. He was okay. You know, oh shit, sorry, I didn’t know, sorry, sorry, sorry.

“So that night we all went into town on a bus. Everybody goes off to do their thing and I headed out in a taxi for a little restaurant, a little out of town. After dinner I go into the bar to have a couple of pops before heading back to get the bus. The other black trainee, Bernice, was off in a corner of the bar. She comes over and sits down. Nice to have a night away from the boys, she said, let’s have a girls’ night out. I right away told her her scene wasn’t my scene. Okay, she said, and we had a couple of drinks and chatted. Just chitchat about this part of the course, that instructor, where we wanted to work when we graduated. It was okay. She had some funny stories about living down south — she was from near Knoxville — and we laughed a lot.

“So we get a taxi and we head back to the bus. We’re walking up the road and there’s the farm boy waiting to board. He sees us and he looks at me funny. I said to Bernie: Oh, shit, he asked me out. I told him I had a hot date tonight. And bang, just like that she’s got her arm around me and twists my face around, plants a big fucking wet one on me. I thought I was going to choke on her tongue. She had a very long tongue. ‘Stuck up cunt,’ she said, ‘see how you like being a dyke.’ All night she’d hated me. All night she just laid back in the weeds and waited for a shot.

“After that I was a dyke. No way to undo it. Don’t even try. All the guys I’d been friendly with, gentle with when they asked me out or flirted, you could see their faces, that Bernice was the honest one — she didn’t hide her flavour. But I’d betrayed them, trying to pass as straight and leading them on. You can hop into bed with a hundred guys after that and it doesn’t matter. Word got around. Boy, did word ever get around. They put me as far away from civilization as they could, way up north where they don’t like blacks particularly, even if they’re Christian blacks. Bar fights, domestics, kids killing themselves huffing gasoline in bags, kids killing each other because … Well, who even knew? Frozen babies, burned babies, beaten babies, chewed babies. Jack-lighters and bear gallbladder poachers and guys who operate moonshine rigs. Laid-off workers hanging themselves from trees like empty pods.”

She lay there a few moments thinking: I’m giving him all the bad stuff. She wondered if she should talk about sudden rivers of fish, kind old men coming by the bright wooden detachment with creels of trout and presenting them in respectful silence, the sickening but soulful smoky smells of sweat lodges, of the open-faced youngest children who came by with beaded god necklaces. Her pre-dawn rounds when she couldn’t sleep, driving the big old cranky four-by-four through the Indian country, through the white trash Christian towns full of churches, wishing she could hate it all but loving it more and more.

“Anyway,” she said, “they call it the Spout up here. If they don’t want you, you go to the Spout and they pour you out.” She turned her head and looked up to see if he was still awake. “Well, they poured me out.”

He had to say something. “And you landed in my cup of love.”

“Oh, Bongo.” She shook with laughter. “Oh, oh, gag.”