Читать книгу A Matter of Simple Justice - Lee Stout - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

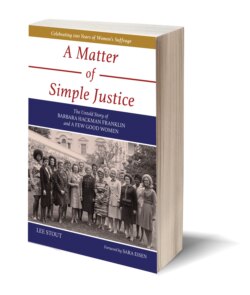

ОглавлениеPREFACE

The late historian Robert V. Daniels called it the “Gender Revolution”—the march of women to legal, political, and economic equality with men over the last century and a half. With a major acceleration over the last forty years, it has resulted in “the most profound social change that America has ever experienced, certainly since the abolition of slavery, perhaps in all its history.”1 And yet we still have not seen its completion, nor do we know how it will turn out, although a return to past attitudes and practices would seem impossible.

The women’s movement has deep roots in our struggles for political and economic equality. By the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, extending equal treatment to women in law and at the ballot box required determined leadership by early feminists as well as fundamental changes in American society. These also inspired women’s participation in reform movements such as abolitionism and the increasing presence of women working outside the home and away from the farm. The first and second world wars expanded the economic role of women but also changed women’s outlook on life. Women increasingly sensed the value of independence for themselves in terms of family life, sexuality, and work.

Back in 1848, the delegates (both male and female) to the pioneering Seneca Falls Convention on Women’s Rights declared that man had “endeavored in every way that he could to destroy [a woman’s] confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.”2 A century later such feelings were still present, but much had changed as well.

The privations of the Great Depression and World War II gave Americans a yearning for “normalcy” and prosperity. By the 1960s, however, an accompanying “sexual counterrevolution,” as Betty Friedan put it,3 had evolved into a conscious antifeminism that disparaged the idea of women’s rights. But with the twin earthquakes of the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, these perceptions could no longer hold. Equality for women in the workplace was no longer just an issue for the factory floor or the secretarial pool. College-educated women increasingly sought entry to management and traditionally male professions.

The oral history project “A Few Good Women: Advancing the Cause of Women in Government, 1969–74” was an archival response to those powerful times. It resulted from my interest in acquiring the papers of Barbara Hackman Franklin, a 1962 graduate of Penn State. At the time, I was the university archivist, and it was my job to preserve the history of Penn State. To do that, we selectively keep the official institutional record, the personal papers of faculty and administrators, and materials from alumni that document student life. In 1992, we decided to expand the idea of alumni collections to more fully record the lives and achievements of our distinguished alumni—those who combine significant service to both Penn State and society at large.

Barbara Hackman Franklin received this award in 1972. Since then she has been a trustee of the university, an active leader in alumni affairs, and a distinguished public servant, most notably as U.S. secretary of commerce from 1992 to 1993. The following year, she launched an international consulting business, and I visited her in her Washington office to discuss her papers. In the course of our conversation, I heard a fascinating story that grew more interesting as Barbara talked about her experiences. It started with a question at a press conference that changed history. As we talked, and later as I read more about it, I realized that this was not an exaggeration.

In 1971, Barbara Franklin was named by President Richard Nixon a special assistant and charged with the responsibility of recruiting women for executive service and leadership in government. This was an extraordinary milestone; there had never been a person specifically tasked with such a role in the entire history of American government. The women she recruited were pioneers who made great advances, but in many cases the beginnings of their careers in the Nixon administration were overlooked. In addition, it struck me at the time that many of these women, whose service in government had started twenty or more years earlier, were advancing in age. It was only a matter of time before we would start to lose them.

I suggested to Barbara that there ought to be an oral history project for these women to record their reminiscences of both the unique journeys they had made and their common experiences in government. Barbara was very interested in this idea, but I set it aside while focusing on bringing her papers to Penn State. She, however, did not let it rest.

One of her first questions, “What is oral history exactly?,” prompted this response on my part. Oral history interviewing is a process of collecting evidence. These are people’s reflections seen through the lens of time, and one person’s perspective may, and likely will, differ from another’s on the same events and topics. Historians use this evidence by interweaving a selection of excerpts from interviews in a book or article, while archivists preserve those interviews so that in the future other researchers will also be able to read and evaluate them and possibly reach different conclusions. This is essential to building an evolving historical consensus.

By the end of 1995, we began to focus more on the prospects for an oral history project. We discussed the potential value and significance of these interviews; we talked about the nature of the interview process; and we discussed the logistics of creating and operating an oral history project. I prepared an outline of what we would need, in particular staff—a project manager, an interviewer, and a transcriptionist.

In 1996, Barbara formed an advisory board and launched the project. They decided that the perfect interviewer would be someone with Washington experience, who knew both the women and the era, to serve in the roles of project manager and interviewer. Jean Rainey, a longtime Washington publicist, fit the bill admirably. After discussions at Penn State about the nature of the project, she began interviewing. Eventually, we would have nearly fifty audio recordings with many of the most significant women who took office during the Nixon administration as well as with some of those tough-minded men who worked with Barbara in the White House Personnel Office.

As the project progressed, we created a website for it on the University Libraries webpages (http://www.afgw.libraries.psu.edu/) and began to see research use of the interviews. However, Barbara had more plans for the project. The first was to foster an extension of the project into the schools by sponsoring a women’s history curriculum project. Penn State education librarian Karla M. Schmit has developed this curriculum for grades six through twelve in two phases with funding from the Aetna Foundation, and it is available online at http://www.pabook.libraries.psu.edu/afgwcur/home.html. This project has also become the basis for Karla’s doctoral dissertation.

A second idea was for a book to describe the history of this experience and to highlight some of the wonderful commentaries that our interview subjects shared with us through their oral histories. That I would have the opportunity to tell this story is both a signal honor and the culmination of more than seventeen years of work with Barbara Hackman Franklin to preserve the recollections and reflections of these amazing women and men.

Many have contributed to this project and deserve acknowledgment. None of this would have happened without the determination and generosity of Barbara Hackman Franklin. Without her, there is no story, no project, and no book. I would also like to thank Wallace Barnes, Barbara’s husband, who has encouraged this effort from its inception. I can’t count the number of times he’s personally flown Barbara back and forth to Penn State for meetings and events. He always has trenchant and useful comments to add to the discussion, and it’s always a pleasure to share a Penn State Creamery ice cream cone with him before he leaves campus.

The members of Barbara’s staff, present and past, especially Maureen R. Noonan, Mackenzie Burr, and Amy Whiteside, along with Kathy Johnpiere, Susanna Knouse, Susan Thigpen, Elizabeth Denny Haenle, Stacey Neary Normington, and Marlene Lyons, have been loyal friends and indefatigable workers on this project.

At Penn State, I’ve had the wonderful support of three successive deans of the University Libraries, Nancy Cline, Nancy Eaton, and Barbara Dewey, as well as Acting Dean Gloriana St. Clair and Assistant Dean for Scholarly Communications Mike Furlough, numerous development directors, Libraries Publications Manager Catherine Grigor, and Assistant to the Dean for External Services Shirley J. Davis. At the Penn State University Press, director Patrick Alexander has been a clear guide to the mysteries of publications and marketing at all times, as has the production and marketing staff of the Penn State University Press.

Among my archival and library colleagues at the Penn State University Archives, current archivist Jackie Esposito and archives staff members Paul Dzyak, Robyn Comly, and Alston Turchetta provided invaluable assistance. Past heads of special collections Charles W. Mann Jr. and William L. Joyce were strong advocates for the oral history project and all that has come from it. For their professional contributions, I also thank Martha Sachs and Heidi Abbey at Penn State Harrisburg’s Alice Marshall Collection, Pamla Eisenberg, Ira Pemstein, and Ryan Pettigrew at the Richard Nixon Library, and the reference staff, especially Ellen M. Shea and Diana Carey, at the Schlesinger Library of the Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. In addition, I extend my warmest gratitude to the Schlesinger Library and to the Rev. Carol Barriger, Vera Glaser’s daughter, for their permission to quote from and cite her mother’s work in this book.

Finally, my wife, Dee, has been my most valuable supporter in this project. She has read every draft of the manuscript, some several times, and is my most helpful critic and editor. This would never have been completed without her encouragement and help.

Lee Stout