Читать книгу American Gandhi - Leilah Danielson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Calvinism, Class, and the Making of a Modern Radical

Character is built by action rather than by thought. Contemplation does not beget virtues. But out of the elements of the daily struggle we mold at last conceptions of justice, parity and truth and build that temple of morality which is the chosen seat of true religion. Finally, it is only through the conflict into which his unrest urges him that man at last finds God. Revelation is powerless if it enlightens only the reason. . . . And faith is valid only when it leads to action, so its ultimate satisfaction is found only in the active life.

—A. J. Muste, 1905

MUSTE WAS BORN in January 1885 in Zierikzee, a port town in the province of Zeeland in the Netherlands. Zierikzee, Muste learned later in life, was apparently the Dutch ‘‘equivalent of our Podunk,’’ small, poor, and remote.1 Indeed, from the nineteenth century to the present, Zierikzee and Zeeland as a whole have had a reputation for economic backwardness and religious orthodoxy. A series of islands located on the extreme southwestern coastal zone of the Netherlands, much of Zeeland actually lies below sea level and is protected by a system of river and sea dikes. This location gave rise to a paradoxical character. On the one hand, as its reputation as the boondocks of the Netherlands suggests, Zeeland was isolated from the mainland. On the other hand, because it was located in the estuaries of some of Europe’s greatest rivers, it was a commercially and strategically important area to control.2

This paradox of isolation and interconnectedness provides the backdrop for Muste’s experiences in the Netherlands, the reasons for his migration to the United States in 1891, and perhaps even a key to his adult character and politics. A close analysis of his childhood and youth reveals that the Dutch American community was less insulated and conservative than Muste characterized it or than historians of Dutch ethnicity have recognized. Despite their best efforts to isolate themselves, the small world of Dutch American Calvinists intersected with larger processes of global capitalism, industrialization and class formation, international migration patterns, urbanization, and cultural changes related to religion and gender. It is in these intersections that it becomes possible to understand the making of a modern radical.

THROUGHOUT the nineteenth century, Zeeland’s economy was like its geography, both remote from and integrated into the world market. As the least urbanized and industrialized province in a country that already lagged far behind its neighbors in its level of modernization, Zeeland had a profoundly rural character. At the same time, however, the development of its rich sea-clay soil was capital and labor intensive, which encouraged concentration and proletarianization. In spite of the expansion in commercial agriculture, Holland’s modern industrial sector did not grow fast enough to absorb the increasing rural population. The result was a rising number of day laborers and servants reliant upon a commercial economy vulnerable to world market fluctuations. True to its reputation, Zeeland led the country in child and infant mortality, death and birth rates, and emigration rates.3

The Mustes were a quintessential Zeeland family.4 The patriarch, Martin (also known as Marinus) Muste, was the second oldest child in a poor family of five or six children. When he obtained a job in Zierikzee as a coachman for the local nobility, the sense was that he had risen ‘‘a bit in the economic scale.’’5 The matriarch, Adriana Jonker, came from a large family of ten or eleven children in the countryside and was, Muste recalled, ‘‘very definitely a peasant woman.’’ Unlike Martin, who had completed the fourth grade and who could read and write, Adriana read with difficulty and she could not write. Her and Martin’s first child, a son, Abraham Johannes, had died in infancy, and they gave their second child the same name. Soon thereafter, Adriana gave birth to three more children, two daughters, Nelley and Cornelia, and a son, Cornelius.6

In spite of his family’s poverty, Muste never had a sense of weariness or desperation and recalled having a contented and happy childhood. His mother was ‘‘an extremely good housekeeper and a good cook,’’ who kept her family clothed and fed. One St. Nicholas Day—the Dutch equivalent of Christmas—stood out in Muste’s memory as being particularly joyful. He must have been about three years old, since only his sister Nelley was present, as they waited by the staircase for Santa Claus. Suddenly, there was a commotion and cinnamon-spiced nuts began rolling down the stairs. ‘‘Then Santa Claus himself came stomping down the stairs, distributing gifts. He left by the front door and in a moment or two mother came back laughing happily. It was a most stimulating and yet soothing sensation to have a real Santa Claus and a real mother at the same time and in the same person.’’7

In later years, Muste would attribute the class culture of his Dutch upbringing to Calvinism. The view of his parents and of the broader Dutch culture was that one had to be contented with one’s station in life because it had been assigned by God. The ‘‘dominant pattern,’’ Muste recalled, was ‘‘acquiescence in the will of God rather than rebellion against it.’’8 Muste’s parents were members of the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederlands Hervormde Kerk), which was established as the state church after the country won its independence from Spain in 1648. John Calvin, of course, was Martin Luther’s successor in the Protestant Reformation. Born in France in 1509, Calvin shared Luther’s core beliefs but took them even further than the reformer. From Luther’s emphasis on God’s saving grace alone, Calvin elaborated the doctrine of predestination, which emphasized the utter estrangement of human beings from God and their powerlessness to affect their salvation.9

Controversies within the Hervormde Kerk would spill over into the Dutch immigrant communities in the United States. In 1834, there was the first of several major secessionist movements. The separatists opposed the state’s recent assertion of supremacy over religious matters, which they viewed as a sign that the church was succumbing to the theological liberalism of the Enlightenment. The Seceder movement grew rapidly in the rural parts of the Netherlands, including Zeeland. State and ecclesiastical authorities viewed the Seceders as a threat and heavily persecuted them. This repression, along with agricultural crises and economic depression, encouraged Seceders to immigrate to the United States, giving them a greater influence in the new country than they had in the old. Although repression waned over the course of the nineteenth century, there was a second secession (known as the Doleantie) in 1886, under the leadership of Abraham Kuyper, and their influence grew tremendously when he was elected prime minister in 1901.10

In contrast to Max Weber’s thesis that Calvinism constituted the cultural arm of capitalist modernization, Seceders tended to be hostile to liberal ideas, while the most economically prosperous and more liberal tended to be members of the Hervormde Kerk or smaller, more liberal Protestant denominations.11 Indeed, the Secession was a counterrevolutionary movement in opposition to the trends unleashed by the French Revolution and the Enlightenment. According to Kuyper, the intellectual leader of the Doleantie, the Enlightenment had made three fundamental errors: ‘‘ ‘Humanism,’ making man the center and measure of reality; ‘Pantheism,’ identifying man and nature with God; ‘Materialism,’ denying the reality of the spiritual and non-empirical.’’ Only ‘‘a restored spiritual ethos’’ would provide ‘‘ties that could harmonize individuals and groups without enslaving them. Only divine authority could check human power; only the transcendent realm gave hope to the oppressed, sound standards of value for public conduct, and dignity to human life.’’ Kuyper was thus both a conservative and a reformer, calling for a return to an organic, patriarchal order that would have little room for plurality and difference, while at the same time recognizing the oppressive tendencies of the modern state and industrial order.12

Calvinism appears severe to modern eyes. Yet it is important to recognize that Calvin did not view predestination as an expression of despair in humanity. Rather, the ‘‘sweet and pleasant doctrine of damnation,’’ as Calvin put it, spoke to the utter majesty of God.13 Certainly Muste did not experience Calvinism or the cultural life of the Reformed Church as stern or dreary. Sunday was for Muste ‘‘the high day of the week—a day of ‘rest and gladness,’ of ‘joy and light.’ ’’14 His family, while reserved, was warm and loving, and found amusement in activities that fell within the moral strictures of the church. Indeed, although he would later reject Calvinistic theological doctrines like predestination, his religious heritage shaped his life and politics long after he left the Reformed Church. In particular, he retained ‘‘a strong conviction about human frailty and corruption’’ and the belief that one’s life must conform to the ‘‘imperious demand’’ of the gospel. Later, in the 1930s and 1940s, when he developed a critique of Marxism and the Enlightenment tradition more broadly, he seemed to echo Kuyper in his insistence that belief in God was ultimately the only way to save humankind from destroying itself. His more skeptical relationship to liberalism and more pessimistic view of human nature differentiated him from his fellow Social Gospel clergy. It would also make him the most thoughtful and insightful pacifist critic of neo-orthodoxy, a theological movement that began after World War I as a reaction to nineteenth-century liberal theology and a positive reevaluation of the Reformed tradition.15

The overwhelming preponderance of Seceders and lower-class members of the Hervormde Kerk in Dutch migration encouraged an earlier generation of historians to emphasize religious over economic factors in influencing Dutch migration. Yet recent scholarship has established the centrality of structural causes.16 Certainly economic considerations influenced the Muste family’s decision to move to the United States. In the 1880s, Holland experienced an agricultural crisis that accelerated the mechanization and consolidation of commercial agriculture in the sea-clay-soil regions. Zeeland was hit especially hard, and during the years 1880 through 1893, it contributed a larger proportion of emigrants than any other province.17

Included among the second wave of Dutch immigration in the 1880s were four of Muste’s maternal uncles, poorly paid agricultural laborers eager to improve their livelihood. The Jonker brothers settled in Grand Rapids, Michigan, home to a substantial Dutch community, where they managed to establish small businesses in groceries, drugs, and scrap metal. ‘‘Having achieved a measure of security for themselves,’’ Muste recalled, ‘‘they considered the plight of their youngest and favorite sister, my mother, and one of them paid us a visit and proposed that our family emigrate.’’18

The journey, which occurred in late January and early February 1891, was long and arduous. Like most immigrants, the family, which included six-year-old Muste and three younger siblings, traveled in steerage, where conditions were cramped and food was scarce. Part of the voyage was stormy; Adriana became sick and had to be taken out of steerage into the ship’s hospital. Still, the experience was a thrilling one; Muste recalled the ‘‘awe’’ of viewing the ‘‘tremendous expanse’’ of the ocean and the excitement of disembarking at New York City’s Castle Garden (the immigration depot that preceded Ellis Island), bustling with people and boats. The family remained at Castle Garden for a month while Adriana recovered in the hospital. Although concerned about his mother’s health, Muste had ‘‘only the happiest of recollections’’ of Castle Garden; the children had the run of the hospital’s corridors, the food was better than they were accustomed to, and, most crucially, the ‘‘atmosphere was a friendly one.’’19

The Muste family’s positive experience at Castle Garden was not unusual. The port was ‘‘so commodious, well-run, and protective of the new arrivals that its fame spread throughout Europe.’’20 But their warm welcome also reflected the fact that the Dutch were considered especially desirable immigrants, in contrast to southern and eastern European immigrants who would succeed them. As Muste drolly recalled, ‘‘there was no barrier of culture as there was to be later with immigrants from Eastern Europe, and no barrier of color as with Negroes or Asians. . . . Almost without exception [the Dutch] were sober and industrious. . . . They were allergic to unions or ‘agitators’ of any kind.’’21

It was at Castle Garden that Muste had his first initiation into late nineteenth-century American nationalism. When one of the attendants learned that Muste’s name was Abraham, he began calling the Dutch boy ‘‘Abraham Lincoln,’’ naming him, as it were, as an American. Even though Muste had no idea who Abraham Lincoln was, when he finally arrived in Grand Rapids, one of his first projects ‘‘was to find out what this Abraham Lincoln meant.’’ The result was a strong identification with the Great Emancipator, an identification no doubt encouraged by the fact that the midwestern city, so close to Illinois, was Lincoln country. ‘‘My education . . . of this country,’’ Muste mused, ‘‘was the picture of the trip down the Mississippi and seeing the slave sold on the block in New Orleans and saying, ‘If I ever have a chance to hit that thing, I’ll hit it hard!’ ’’ By the time he was nine years old, he had memorized the entire Gettysburg Address.22

In later years, Muste would reflect that his largely positive experience of emigration and immigration might offer a key to understanding his character and adult political commitments. The ocean voyage had ‘‘its apprehensions,’’ but it ultimately had a ‘‘happy ending.’’ This taught him that ‘‘the peril is not to move when the new situation develops, the new insight dawns, the new experiment becomes possible.’’ Just as the biblical Abraham went out to find ‘‘a city which existed—and yet had to be brought into existence,’’ divinity was to be found in the history of human work and creation. History was, moreover, a ‘‘movement toward a goal.’’23 As Muste’s references to Abraham suggest, this philosophy of history as a joint project of human beings and God toward the city-which-is-to-be is deeply rooted in both Judaism and Christianity and helped to shape the progressive view of history that has characterized Western political thought since the Enlightenment. Certainly it encouraged Muste, along with others of his generation, to view political activism as a religious imperative.

As Muste’s rapid assimilation into the drama of the Lincoln republic reveals, many Hollanders quickly identified with the new nation. For them, Muste recalled, the United States was ‘‘a land of opportunity and freedom, the land to which God had led the Pilgrim fathers, a land where youth was not conscripted, and a Christian land, though unfortunately not entirely peopled by orthodox Calvinists.’’24 Yet Muste’s caveat is an important one, and it helps to explain why the Dutch retained a distinct ethnic identity even as they outwardly blended with other northern and western European immigrants. As the rich historiography of religion in nineteenth-century America has shown, the Second Great Awakening in the 1830s spread the idea that individuals had the right of private judgment in spiritual matters and the possibility of salvation through faith and good works. The culture of American Protestantism was, in other words, an evangelical one, imbued with an antinomianism that was anathema to pietistic Dutch Calvinists.25

The Dutch Americans’ relationship to the new country, and their politics, reflected their differences with mainline Protestantism. On the one hand, they praised the United States, became staunch allies of the conservative wing of the Republican Party and the business community, and, with the exception of temperance, did not participate in the reform movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. On the other hand, they often expressed deep ambivalence about American culture; it seemed too individualistic, superficial, materialistic, and Methodist, and appeared to threaten ‘‘the very core of the community’s existence.’’ The problem, they concluded, was theological: ‘‘the substitution of individualistic for covenantal (i.e. corporate) theology.’’ This corporatism encouraged them to sympathize with labor and support pro-labor legislation, even as they opposed unions as anti-Christian institutions.26

As the Dutch struggled to define themselves in a new land, their ethnicity and Calvinist heritage became deeply intertwined, giving them a cultural persistence that defies the paradigm of western and northern European assimilation.27 They did not rapidly assimilate and intermarry with the broader society. Although they integrated into American economic and political life, their cultural life remained largely separate. In church, school, marriage, and recreation, ‘‘the Calvinists built an institutional fortress and demonstrated their religious solidarity.’’28

Grand Rapids offers a case study in Dutch cultural persistence. In the 1890s, when the Mustes immigrated to the United States, Grand Rapids was a classic midsized, nineteenth-century midwestern city, with a rapidly growing population of just over sixty thousand residents. A frontier outpost for much of the antebellum period, it had been transformed by the transportation and communications revolution that integrated the nation over the course of the nineteenth century. By the time of the American Civil War, railroad and telegraph lines linked the city with distant urban markets. Soon, Grand Rapids became a manufacturing center, its famous river lined with furniture factories and working-class neighborhoods, peopled by immigrants from the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, and Canada.29

The Dutch composed the largest of Grand Rapids’ immigrant groups; in 1900, 40 percent of the city’s population was of Dutch birth or ancestry.30 Dutch immigrants first began streaming into Michigan in the late 1840s, when the Reverend Albertus C. Van Raalte led a group of Dutch Seceders to western Michigan, where they established Holland, the first of several Dutch kolonies. Gradually, many of these rural pioneers trickled into the village of Grand Rapids, where they were joined by succeeding waves of their compatriots.31 As the Dutch presence in the city grew, the number of Reformed churches multiplied, along with Christian schools, which maintained instruction in the Dutch language and educated immigrant children in Reformed doctrine.32

Within the Reformed Church, doctrinal and cultural questions became inseparable, as quarrels over theology intersected with the thorny issue of Americanization. Despite Van Raalte’s reputation as a zealous reformer, he had affiliated and built close ties with the Reformed Church in America (RCA), which had deep roots in North America. Strict on doctrine and religious piety, Van Raalte also stressed the importance of learning the English language and encouraged rapid naturalization. Opposition to Van Raalte’s concept of Americanization soon emerged, as dissenters questioned affiliation with the American church, which they charged with insufficient orthodoxy. In 1857, the separatists founded the Christian Reformed Church (CRC), which had ‘‘a more gloomy view of the new country,’’ represented by its decision to hold services in the Dutch language into the twentieth century.33 Nevertheless, whether CRC or RCA, wherever orthodox Reformed pietism was preached, its themes were ‘‘human sin and the need for salvation, human dependence and God’s mercy, the inevitability of suffering and tribulation and the need for penitence.’’34

The proliferation of Reformed churches and doctrinal disputes between them speak to the vibrancy of the Dutch community that greeted the Muste family when they finally arrived in Grand Rapids.35 The Mustes settled into a house a block away from the Quimby furniture factory, where the Jonker brothers had obtained a job for Muste’s father. Six out of ten families who lived on Quimby Street were Dutch, and approximately 60 percent of the Dutch who lived in the neighborhood were unskilled laborers who hailed from Zeeland. There were also Dutch grocers and butchers and shoe stores and clothing stores. The church the Mustes attended held services in Dutch, and Muste attended a Dutch parochial school.36

It would be a mistake, however, to characterize the Dutch American community and particularly the Mustes as thoroughly isolated and remote from the dominant culture. Soon after they arrived, Adriana and Martin decided to join the RCA and not the CRC, despite the fact that several of the Jonker brothers held prominent positions within the latter church. While it is difficult to know the precise reasons for the Mustes’ decision, the implications cannot be exaggerated; even though the RCA was theologically orthodox, it was more open to the dominant culture and affiliated with the established and substantial Reformed community on the East Coast, where Muste would later attend seminary and ultimately break with Calvinism. After Muste had attended two years of parochial school, Adriana and Martin also decided to send him and his siblings to public school. Moreover, the neighborhood in which the Mustes lived was more heterogeneous than other Dutch neighborhoods. ‘‘We had . . . the impression that these Americans were likely not as orthodox as [us] and that some of their behavior was questionable behavior,’’ Muste recalled, but ultimately the walls between them were ‘‘very thin.’’37

Martin Muste’s work also brought him in contact with Americans and other nationalities. The furniture industry dominated the city’s manufacturing sector and the working-class neighborhood in which the Mustes lived. Down the street and across the railroad tracks were a slew of furniture factories that provided work for an estimated one-third of the city’s laborers. Native-born workers provided the skilled labor, while Dutch immigrants, along with a growing number of Poles, provided the semiskilled and unskilled labor. Working conditions were dangerous, hours were long, and child labor was not uncommon.38 Still, ‘‘impersonality’’ had not yet appeared; Muste recalled of his summers working as a teenager that ‘‘the speed up . . . is much greater now than it was then. The factories I worked in were always comparatively small ones. Everybody knew everybody else. They were neighbors and it was pleasant to spend the time with them.’’39

The class culture of the furniture industry was a paternalistic one. Management was vociferously antiunion; it formed an employers’ association with detailed records about each worker’s wages, productivity, and union sympathies to which banks had access.40 Much to the dismay of union organizers, Dutch immigrants, including Martin, were largely hostile to unionism, and the mass of the industry’s laborers remained unorganized until the 1930s. As Muste recalled, ‘‘there was a general attitude in the Dutch churches that labor was associated with socialism and not a thing for Christian people.’’41 The strong presence of the conservative Dutch and the dominance of the furniture industry meant that Grand Rapids was known for many years as an ‘‘open-shop’’ town. Still, there was a residual labor culture; the Knights of Labor had been strong in the city until 1886, and skilled workers like the Woodcarvers and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners were active in the Trades and Labor Council, which organized a Labor Day parade every year that brought the Mustes and other residents out in droves.42

Muste’s childhood in Grand Rapids revolved around neighborhood, school, and church. The Mustes, who now had a fifth child, Willemina, lived in a small, drab house that belonged to the owners of the Quimby furniture factory. Next to the house was the lumberyard, where the Muste children played hide-and-seek; to the west was the Quimby lumber mill where Martin worked; and directly across the street was the ‘‘big house,’’ where the Quimby family lived. Muste frequently played with Irving Quimby, who was about the same age, despite Adriana’s fears that Martin would be fired for the presumption. Irving introduced Muste to the Quimby family library where, ‘‘breathlessly,’’ Muste read bound volumes of Harper’s and Century, which had been running series of articles on the Civil War that filled his head with romantic accounts of battles, marches, and sieges. Veterans who lived nearby at the Old Soldiers Home enthralled Muste as they tramped by on their way downtown, where—he later learned—they bought booze. Occasionally he managed to get one of them to talk. ‘‘What a day that was!’’43

School was for Muste an ‘‘utter fascination.’’ From the time he started he was the best speller and reader in the class. ‘‘School never started too early in the morning for my taste. The school day always seemed to rush by. The start of vacation was in its way an occasion, but the opening day of school after Labor Day was a much more joyful and momentous one.’’ There, his budding identity as an American was imbued with the missionary nationalism that was characteristic of nineteenth-century political culture. As Muste recalled of the ideological milieu in which he was raised, ‘‘Americans thought of themselves as the chosen people who were to bring the blessings of Christianity, democracy, prosperity and peace to all mankind.’’ ‘‘The Civil War had, of course, been a traumatic experience. . . . By the eighteen-nineties, however, the image that was communicated to us in the schools . . . [was that] God, in his inscrutable Providence, had inflicted upon us the tragedy of the war experience. The nation, North and South, had been crucified on the Cross of War. Did not the Bible teach that ‘without shedding of blood there is no remission of sin’?’’ Now, however, ‘‘the union was indissoluble.’’44

Impressed by the Dutch boy’s intellectual abilities, Muste’s teachers took a special interest in him. In eighth grade, the principal of his school encouraged him to write an essay on child labor for an annual contest sponsored by the Trades and Labor Council that he won. It is tempting to interpret Muste’s denunciation of child labor as growing out of his own experience, since, starting at age eleven, he spent his summers laboring with his father at the factory, but the principal furnished him with the research he used to write the essay. But it does tell us something about the twelve-year-old boy’s worldview. The essay, which reads like a sermon, begins by suggesting in Social Darwinist fashion that child labor ‘‘is the result of the brute nature in man; of the oppression of the weak by the strong.’’ It then provides a subtle yet ultimately conservative class analysis: ‘‘the rich oppressed the poor and made the children work,’’ which resulted in the emasculation of the male breadwinner, who becomes a loafer, ‘‘blaming the capitalists and the government,’’ while the mother nags incessantly. Fortunately for the American people, child labor was not as widespread in the United States as it was in England. The essay concludes didactically, with an appeal to follow the golden rule.45

Muste’s prize for winning the contest was $15 worth of books and publication of the essay in the Labor Day souvenir book, ‘‘one of the great experiences in my life.’’ Several of the books he chose indelibly shaped his character. An anthology of poems ‘‘helped develop a love for poetry which has been one of life’s greatest and most enduring joys’’; J. B. Green’s History of England fostered a lifelong interest in history; and, finally, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Essays had a ‘‘seminal influence. . . . With Lincoln, Emerson was a creator of that ‘American-Dream,’ which, along with the great passages of the Hebrew-Christian Scriptures, molded and nourished my mind and spirit.’’46

Muste’s reference to Emerson shows how public education exposed him to alternative worldviews. In contrast to the corporatist, determinist, and antiliberal thrust of the Reformed Church, Emerson preached a more modern creed of ‘‘self-reliance,’’ of the divinity within each person and of the self’s capacity for ‘‘an original relation to the universe.’’ His question was not ‘‘What can I know?’’ but ‘‘how can I live?’’47 Muste the prepubescent boy was hardly aware of the tensions between transcendentalism and Calvinism, but he was strongly influenced by the Emersonian idea that the divine exists in every person, and that religion is realized in action and experience, not theological verities. These beliefs would eventually draw him—as they did Emerson—away from the formal ministry into Quakerism, nonconformity, and mysticism. They would also draw him to pragmatism, a philosophy developed by Emerson’s godson, William James, which held that individual self-realization and democratic practice were inseparable.

Indeed, one of the arguments of this book is that Muste must be placed in the tradition of religious humanism associated with figures like Emerson and William James. Emerson, and transcendentalism more broadly, ‘‘insists, first, that the well-being of the individual—of all the individuals—is the basic purpose and ultimate justification for all social organizations and second that autonomous individuals cannot exist apart from others.’’ By making the individual and his or her soul central to the modern project, transcendentalism offers an alternative to ‘‘utilitarian liberalism,’’ on the one hand, and to ‘‘leader worship’’ and ‘‘collectivism,’’ on the other. ‘‘It is the ambition, if it has not yet been the fate,’’ writes one of Emerson’s most notable biographers, ‘‘of transcendentalism to provide a soul for modern liberalism and thereby to enlarge the possibilities of modern life.’’ This idea constitutes ‘‘the central truth of religious—not secular—humanism, the idea that is also the foundation of democratic individualism.’’ Certainly, as we shall see, it was Muste’s ‘‘central truth,’’ providing form to the many twists and turns of his long public career.48

Muste’s rhetorical facility was not only fostered by public school, but also by the church, which was at the center of the family’s cultural life.49 When his family entered the church on Sunday mornings, Muste felt as though he had ‘‘entered another world, the ‘real’ world . . . ‘to Mount Zion, the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem.’ ’’50 Years of Sunday school taught him to sermonize and, at age eleven, he gave his first sermon on the meaning of Christmas; the following year he discoursed on ‘‘Jesus, as Prophet, Priest and King.’’ There was never a moment of doubt that he was destined for the ministry. In fact, there was no real choice in the matter; as the eldest son, his family and community expected that he would honor them by becoming a minister. But Muste’s sense of destiny for the ministry also reflected his religious sensibility. At the age of thirteen, he had a mystical experience in which he was overcome by a sense of wonder and divine presence. ‘‘Suddenly,’’ Muste recalled of this moment, ‘‘the world took on a new brightness and beauty; the words, ‘Christ is risen indeed,’ spoke themselves in me; and from that day God was real to me.’’ Soon thereafter, he received confirmation, whereas most were not confirmed until age eighteen. In later years, he would come to see his youthful mysticism as a nascent expression of pacifism.51

Having displayed his oratorical talents and religious sophistication, Muste was given a scholarship to attend the preparatory academy attached to Hope College, an RCA denominational college located in Holland, a small, largely Dutch community about twenty-five miles west of Grand Rapids. Hope offered Muste a safe, nurturing environment for the maturation of his intellect and his spirit, while also providing him with experiences and opportunities that drew him outward, away from the known into the unknown.52

Hope offered a classical liberal education that was largely isolated from the new intellectual climate of biblical criticism and Darwinian biology. But by the turn of the century, outside currents had begun to creep in. The college created a department of physics and chemistry and a department of biological science, and the library began to accumulate a small collection of science books. Although secondary students were not allowed to read the heretical texts, Muste had access to them because of his job in the library. He also learned a new ‘‘point of view’’ from the new professor of biology Samuel O. Mast, the first and only faculty member ‘‘who was a scientist in the modern sense of the term,’’ a vocation that created some tension between him and the college administration. He forced his students, Muste among them, to perform dissections rather than read about them.53

Involvement in extracurricular activities such as the YMCA and intercollegiate athletics also exposed Muste to the outside world. When Muste first arrived at Hope, ‘‘we didn’t have any intercollegiate athletics at that point. That was considered rather unorthodox and rather wild.’’ By the time he entered his freshman year, however, the college had grudgingly admitted that physical exercise, when not taken too far, could promote ‘‘Christian character.’’54 The idea that new, muscular bodies of Christians would be better equipped to spread the gospel had already made deep inroads into mainline Protestantism, and at the turn of the century had just begun to penetrate conservative churches such as the RCA, due largely to the efforts of the YMCA. Muscular Christianity was the religious counterpart of the redefinition of American manliness associated with Theodore Roosevelt’s cult of the strenuous life. While the old model ‘‘stressed stoicism, gentility, and self-denial,’’ the new, Progressive model of American manhood stressed action and aggression, attributes intimately connected to Social Darwinist notions of civilization, progress, and race.55

Hope students, including Muste, heartily assented to these ideas. He was an active member of the campus chapter of the YMCA, helped lead the campaign for intercollegiate athletics at Hope, and, later, led the college to two state basketball championships as captain of the Flying Dutchmen.56 He also served on the editorial board of the student newspaper, the Anchor, which was suffused with the language of muscular Christianity. As one 1905 editorial, probably written by Muste, put it, ‘‘In a college such as ours where so many profess to be Christians one is apt to lose sight of the serious, strenuous side of Christianity, because there is not the incessant conflict with sin that is forced upon one when in the presence of the positive evil in the world of active life.’’57 His 1903 oratory on the Polish king John Sobieski, which won the Michigan state championship, similarly reveals a preoccupation with establishing the criteria for Christian manhood: ‘‘By what standard shall we determine a man’s greatness?’’ He concludes that what made Sobieski ‘‘the Lincoln of Poland’’ was not just his use of force, but his principled stand for ‘‘civilization’’ and Christianity against the ‘‘barbarism’’ of the Turks.58

These treatises provide us with a glimpse of the teenage Muste’s world-view. He appears fixated on the question of how to be both manly and Christian. Over and over again, he argues that the man of words can be a hero so long as he exhibits character traits like courage, sincerity, and a willingness to take action and struggle. Like his heroes John Sobieski and Abraham Lincoln, he pines for an ‘‘important mission’’ that will inspire him ‘‘to conquer and to die on humanity’s behalf.’’59 These gendered concerns have a weighty quality to them; his writing is heavy with the nineteenth-century style in which Greek mythology and history, scripture, Victorian sentimentalism, and notions of Western progress and civilization blend together in ways that appear self-important to twenty-first-century eyes. Still, a softer side to Muste occasionally makes an appearance, like an Emersonian ode to nature’s beauty and another on the importance of honoring poets, not just warriors and statesmen.60

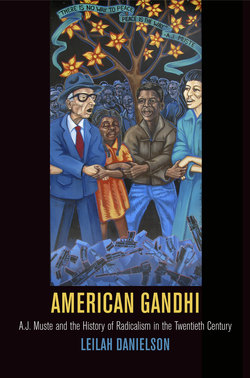

FIGURE 1. A. J. Muste (holding ball) as captain of the Flying Dutchman basketball team. 1904–5. (Joint Archives of Holland)

FIGURE 2. A portrait of the Muste family a year before Martin Jr.’s death from bronchitis. Front row, left to right: Martin Muste, Martin Jr., and Adriana Muste. Back row, left to right: Cornelia, A. J., Nellie, Cornelius, and Minnie. Circa 1906. (Marian Johnson)

Meanwhile, back at home, life continued as usual. The Mustes attended the same church and lived in the same neighborhood, Martin continued to work in the furniture industry, and Adriana continued to keep house and raise children, including a third son, Martin Jr., who was born in 1902 (and who would die of bronchitis in 1907, when he was four years old).61 Martin and Adriana were proud of their eldest son; after all, ‘‘the height of a parent’s ambition in that environment [was] that the older son should get an education,’’ especially if he planned to enter the ministry. But they expressed this pride with characteristic modesty and ‘‘matter-of-factness.’’62 According to friends, family, and acquaintances, Muste shared his parents’ humble and unassuming character, which seems to contradict the confident and masculine image of him that emerges from his college days, suggesting that we must be cautious about drawing neat conclusions based upon the flourishes of a nineteenth-century rhetorical style.63

As Muste neared graduation, he began to chafe under the cultural and intellectual limitations of his milieu.64 As the new editor of the Anchor, he called for more intercourse with other schools and for the paper to serve as ‘‘the voice of the studentry [sic] in earnest criticism and sincere demand for reform.’’65 His valedictory speech, entitled ‘‘The Problem of Discontent,’’ provides further evidence for his growing restlessness. The speech is a classic statement of Social Darwinism, with its themes of race progress and civilization, struggle and conflict. But, perhaps revealingly, Muste compares the drama of historical progress to the individual, who is filled with doubt, dissatisfaction, and impatience, particularly ‘‘in matters of religion.’’ ‘‘What is the solution of this problem of unrest? Why this eternal restlessness? Where is surcease from sorrow?’’ Just as with civilizations, the answer was a ‘‘life of action and of usefulness’’ that builds character and brings the individual closer to God. ‘‘The god of philosophy is an abstraction. The God of experience is personality, power, and love.’’66

It is difficult to discern a budding pacifist in martial texts such as these, but one can detect a nascent reformer. Muste had clearly begun to question ‘‘his early faith,’’ a drama that would eventually inform his interest in modern theology. He had also imbibed the culture of muscular Christianity, a seedbed both of empire and of reform. Like so many Protestants of his generation, he associated the religious life with engagement, rather than retreat; he was open to the outside world and what it had to offer. His identification with Lincoln and Emerson may have further nurtured a penchant for reform; Lincoln was for him the ‘‘great emancipator,’’ while Emerson gave a noble purpose to the realization of self. In the right context, moreover, there were elements within the Calvinist worldview that could encourage a stance critical of the United States and its institutions. Calvinist anti-individualism and ambivalence toward American culture might lead to a sympathy toward labor and collective action and to criticism of the industrial order. Calvinist suspicion of the modern state might lead to support for civil liberties and an expansive, democratic society.

Finally, as much as Muste embraced the conservative ideology of Social Darwinism, he was decidedly working class at a time of great industrial unrest. The turn-of-the-century United States was rife with class conflict, competing political ideologies and worldviews that sometimes even made their way into Grand Rapids. Temperance and suffrage campaigns shook up the city; eastern and southern European immigrants brought traditions of labor radicalism to the furniture industry, leading to efforts at unionization that culminated in the Great Furniture Strike of 1911, which ended in defeat for unskilled and semiskilled factory workers like Martin Muste.67 With his working-class background, immense thirst for experience, and enormous intellectual talents, it is hard to imagine that A. J. Muste could avoid being shaken by his 1906 move to the New York metropolitan area, alive with cultural and political ferment and change.

But in 1905, on the eve of his graduation from college, Muste was a fairly conventional, conservative young American man. Despite his status as an immigrant and the son of a factory worker, he was a nationalist, imbued with notions of American exceptionalism and mission. In conformity with the expectations of his parents and his community, he was eager to attend the New Brunswick Theological Seminary in New Jersey and become an ordained minister in the Reformed Church in America. His romance with a Dutch Reformed minister’s pretty daughter, Anne Huizenga, further promised upward mobility. As we shall see, these ambitions would be amply rewarded, and yet Muste would eventually risk it all for pacifism, civil liberties, and socialism.