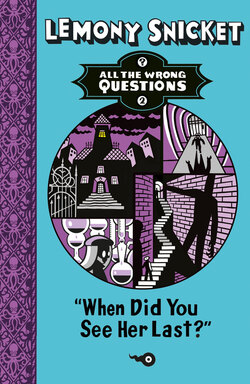

Читать книгу When Did You See Her Last? - Lemony Snicket - Страница 9

Оглавление

The pen-shaped tower had a surprisingly small door printed with letters that were far too large. The letters said INK INC., and the doorbell was in the shape of a small, dark ink stain. It was the name of the largest business in Stain’d-by-the-Sea. Theodora stuck out a gloved finger and rang the doorbell six times in a row. There was not a doorbell in the world that Theodora did not ring six times when she encountered it.

“Why do you do that?”

My chaperone drew herself up to her full height and took off her helmet so her hair could make her even taller. “S. Theodora Markson does not need to explain anything to anybody,” she said.

“What does the S stand for?” I asked.

“Silence,” she hissed, and the door opened to reveal two identical faces and a familiar scent. The faces belonged to two worried-looking women in black clothes almost completely covered in enormous white aprons, but I could not quite place the smell. It was sweet but wrong, like an evil bunch of flowers.

“Are you S. Theodora Markson?” one of the women said.

“No,” Theodora said, “I am.”

“We meant you,” said the other woman.

“Oh,” Theodora said. “In that case, yes. And this is my apprentice. You don’t need to know his name.”

I told them anyway.

“I’m Zada and this is Zora,” said one of the women. “We’re the Knight family servants. Don’t worry about telling us apart. Miss Knight is the only one who can. You’ll find her, won’t you, Ms Markson?”

“Please call me Theodora.”

“We’ve known Miss Knight since she was a baby. We’re the ones who took her home from the hospital when she was born. You’ll find her, won’t you, Theodora?”

“Unless you would prefer to call me Ms Markson. It really doesn’t matter to me one way or the other.”

“But you’ll find her?”

“I promise to try my best,” Theodora replied, but Zada looked at Zora—or perhaps Zora looked at Zada—and they both frowned. Nobody wants to hear that you will try your best. It is the wrong thing to say. It is like saying “I probably won’t hit you with a shovel.” Suddenly everyone is afraid you will do the opposite.

“You must be worried sick” is what I said instead. “We would like to know all of the details of this case, so we can help you as quickly as possible.”

“Come in,” Zada or Zora said, and ushered us inside a room that at first seemed hopelessly tiny and quite dark. When my eyes adjusted to the dark, I could see that what had first appeared to be walls were large cardboard boxes stacked up in every available place, making the room seem smaller than it really was. The dark was real, though. It almost always is. The smell was stronger once the door was shut—so strong that my eyes watered.

“Excuse the mess,” said one of the aproned women. “The Knights were just packing up to move when this dreadful thing happened. Mr and Mrs Knight are beside themselves with worry.”

Zada’s and Zora’s eyes were watering too, or perhaps they were crying, but they led us through the gap between the boxes and down a dark hallway to a sitting room that appeared to have been entirely packed up and then unpacked for the occasion. A tall lamp sat in its box with its cord snaking out of it to the plug. A sofa sat half out of a box shaped like a sofa, and in two more open boxes sat two chairs holding the only things in the room that weren’t ready to be carried into a truck: Mr and Mrs Knight. Mr Knight’s chair was bright white and his clothes dark black, and for Mrs Knight it was the other way. They were sitting beside each other, but they did not appear to be beside themselves with worry. They looked very tired and very confused, as if we had woken them up from a dream.

“Good evening,” said Mrs Knight.

“It’s morning, madam,” said either Zada or Zora.

“It does feel cold,” Mr Knight said, as if agreeing with what someone had said, and he looked down at his own hands.

“This is S. Theodora Markson,” continued one of the aproned women, “and her apprentice. They’re here about your daughter’s disappearance.”

“Your daughter’s disappearance,” Mrs Knight repeated calmly.

Her husband turned to her. “Doretta,” he said, “Miss Knight has disappeared?”

“Are you sure, Ignatius dear? I don’t think Miss Knight would disappear without leaving a note.”

Mr Knight continued to stare at his hands, and then blinked and looked up at us. “Oh!” he said. “I didn’t realize we had visitors.”

“Good evening,” said Mrs Knight.

“It’s morning, madam,” said either Zada or Zora, and I was afraid the whole strange conversation was about to start up all over again.

“We’ve come about Miss Knight,” I said quickly. “We understand she’s gone missing, and we’d like to help.”

But Mr Knight was looking at his hands again, and Mrs Knight’s eyes had wandered off too, toward a doorway at the back of the room, where a round little man was gazing at all of us through round little glasses. He had a small beard on his chin that looked like it was trying to escape from his nasty smile. He looked like the sort of person who would tell you that he did not have an umbrella to lend you when he actually had several and simply wanted to see you get soaked.

“Mr and Mrs Knight are in no state for visitors,” he said. “Zada or Zora, please take them away so I can attend to my patients.”

“Yes, Dr Flammarion,” one of the aproned women said with a little bow, and motioned us out of the room. I looked back and saw Dr Flammarion drawing a long needle out of his pocket, the kind of needle doctors like to stick you with. I recognized the smell and hurried to follow the others out of the room. We made our way through a skinny hallway made skinnier by rows of boxes, and then suddenly we were in a kitchen that made me feel much better. It was not dark. The sunlight streamed in through some big, clean windows. It smelled of cinnamon, a much better scent than what I had been smelling, and either Zada or Zora hurried to the oven and pulled out a tray of cinnamon rolls that made me ache for a proper breakfast. One of the aproned women put one on a plate for me while it was still steaming. Anyone who gives you a cinnamon roll fresh from the oven is a friend for life.

“What’s wrong with the Knights?” I asked after I had thanked them. “Why are they acting so strangely?”

“They must be in shock from their daughter’s disappearance,” Theodora said. “People sometimes act very strangely when something terrible has happened.”

One of the aproned women handed Theodora a cinnamon roll and shook her head. “They’ve been like this for quite some time,” she said. “Dr Flammarion has been serving as their private apothecary for a few weeks now.”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“Flammarion is a tall pink bird,” Theodora said.

“An apothecary,” continued the woman, more helpfully, “is something like a doctor and something like a pharmacist. For years Dr Flammarion worked at the Colophon Clinic, just outside town, before coming here to treat the Knights. He’s been using a special medicine, but they just keep getting worse.”

“That must have been very upsetting for Miss Knight,” I said.

Zada and Zora looked very sad. “It made Miss Knight very lonely,” one of them said. “It is a lonely feeling when someone you care about becomes a stranger.”

“So Miss Knight has no one caring for her,” Theodora said thoughtfully. The cinnamon rolls were the sort that is all curled up like a snail in its shell, and my chaperone had unraveled the roll before starting to eat it, so both of her hands were covered in icing and cinnamon. It was the wrong way to do it. She was also wrong about no one caring for Miss Knight. Zada and Zora were the ones who were beside themselves with worry. I leaned forward and looked first at Zada and then at Zora, or perhaps the other way around. And then, while my chaperone licked her fingers, I asked the question that is printed on the cover of this book.

It was the wrong question, both when I asked it and later, when I asked the question to a man wrapped in bandages. The right question in this case was “Why was she wearing an article of clothing she did not own?” but this is not an account of times when I asked the right questions, much as I wish it were.

“Miss Knight was with us yesterday morning,” one of the women said, using her apron to dab at her eyes. “She was sitting right where you are sitting now, having her usual breakfast of Schoenberg Cereal. Then she spent some time in her room before going out to meet a friend.”

“Who was this friend?” I asked.

“She didn’t say. She just drove off, and she hasn’t come back.”

“She’s old enough to drive?”

“Yes, she got her license a few months ago, and her parents bought her a shiny new Dilemma.”

“That’s a nice automobile,” I said. The Dilemma was one of the fanciest automobiles manufactured. It was claimed that you could drive a Dilemma through the wall of a building and emerge without a dent or scratch, although the building might collapse.

“Mr and Mrs Knight give their daughter whatever she wants,” the aproned woman said. “New clothes, a new car, and all sorts of equipment for her experiments.”

“Experiments?”

“Miss Knight is a brilliant chemist,” Zada or Zora said proudly. “She often stays up all night working on experiments in her bedroom.”

“I imagine she learned that from watching you cook,” I said. “This cinnamon roll is the best I have ever tasted.”

Complimenting someone in an exaggerated way is known as flattery, and flattery will generally get you anything you want, but Zada and Zora were too worried to offer me a second pastry. “She probably inherited her abilities from her grandmother,” the woman said. “Ingrid Nummet Knight founded Ink Inc. when she was a young scientist, after years of experimenting with many different inks from many different creatures. Before long Ink Inc. made the Knights the wealthiest family in town. But those days are over. Ink Inc. is almost finished, and so is the town. That’s why we’re leaving Stain’d-by-the-Sea.”

“When are you leaving?” I asked.

“Whenever the Knights give the word.”

“Even if Miss Knight doesn’t come back?”

“What can we do?” asked the other woman sadly. “We’re only the servants.”

“Then make me some tea,” said an eager voice from the doorway. The bright kitchen seemed to grow darker as Dr Flammarion strolled into the room, took a cinnamon roll without asking, and sat down loudly.

“We were talking about Miss Knight,” one woman said quietly.

“Very worrisome,” the apothecary agreed, with his mouth full. “But at least her parents are resting comfortably. They were shocked to hear of the disappearance. I gave them an extra injection of medicine so that they might pass the afternoon in a comfortable state of unhurried delirium.”

“What medicine is it, Doctor?” I asked.

Dr Flammarion frowned at me. “You’re a curious young man,” he said.

“I’m sorry, Dr Flammarion,” Theodora said. She had finished her cinnamon roll and was wiping her fingers on the photograph of the missing girl. “My apprentice has forgotten his manners.”

“It’s quite all right,” Dr Flammarion said. “Curiosity tends to get little boys into trouble, but he’ll learn that soon enough for himself.” He offered me his nasty smile like a bad gift, and then said quickly, “The medicine I gave them is called Beekabackabooka.”

I have never been to medical school and am never quite sure how to spell the word “aspirin,” but I still knew that Beekabackabooka is not a medicine of any kind. It didn’t matter. Even without his revealing himself to be a liar, I knew there was something suspicious about Dr Flammarion, and even without his telling me, I knew the medicine he was giving the Knights was laudanum. I recognized the smell from an incident some weeks earlier, when people had tried to sneak some into my tea. This incident is described in my account of the first wrong question, on the rare chance you have access to, or interest in, such a report.

“It must be difficult to care for Mr and Mrs Knight all by yourself,” I said, and looked him in the eye. He blinked behind his glasses, and his beard tried harder to flee from his nasty smile.

“I’m not quite all by myself, young man,” he told me. “I have a nurse who is good with a knife.”

Theodora stood up. “I want to conduct a thorough search of the scene of the crime,” she said.

“What crime?” Dr Flammarion said.

“What scene?” I asked.

“It seems likely a terrible crime has been committed,” Theodora said firmly, with no thought to how much that would upset the two women who cared for Miss Knight.

“As the Knight family’s private apothecary, I must say that I’m not sure a crime has been committed at all. Miss Knight likely just ran away, as young girls often do.”

The two servants looked at each other in frustration. “She wouldn’t have run away,” one of them said, “not without leaving a note.”

“Who knows what a wealthy young girl will do?” Dr Flammarion said with a smooth shrug. “In any case, I told Zada it was not worth alarming the police.”

“Zora,” she corrected him sharply.

“I’m sorry, Zora,” Dr Flammarion said with a little bow that indicated he was not sorry at all.

“I’m Zada,” she corrected him again, “but it’s true. Dr Flammarion stopped Zora from calling the police and suggested we call you instead.”

“The good doctor made a good choice,” Theodora said in a tone of voice she probably thought was reassuring, and then stood up and made a dramatic gesture. “Nevertheless, I would like to search the place Miss Knight was last seen. Take me to her bedroom!”

There was no arguing with S. Theodora Markson when she began to gesture dramatically, so I followed my chaperone as she followed Zada and Zora through the packed-up house, with Dr Flammarion close behind me, his breath as unpleasant as the rest of him. Soon we were in a room I recognized from the photograph, which Theodora put down on a brand-new desk in order to rifle through the clothing in the closet. There was no sense in it. This was not the place Miss Knight was last seen. It was simply the place Zada and Zora had seen her last. The girl had driven off in a fancy automobile. It was likely someone else had seen her afterward.

“This room isn’t packed up,” I said.

“Miss Knight wants to do it herself,” one of the women said, “but she hasn’t packed up anything but a few items of clothing.”

That made me ask a question that was closer to the right question than I knew. “What was she wearing when she left?”

Zada or Zora pointed to the photograph. “See for yourself,” she said. “We took that photograph yesterday morning, at her request. It was a lucky thing. Now that photograph is all over town.”

I looked at the picture again. Nothing seemed familiar, but the pink hat looked out of place. “That’s an unusual cap,” I said. “Do you know where she got it?”

“Snicket,” Theodora said sternly. “A young man should not take an interest in fashion. We have a crime to solve.”

Dr Flammarion smiled at me again, and I looked down at the desk rather than look at either my chaperone or this suspicious doctor. In the middle of the tidy desk was a plain white sheet of paper with nothing on it. No, Snicket, I thought. That’s not right. Here and there were tiny indentations, as if something had scratched at it. I leaned down to the desk and inhaled, and for the second time since I entered the tall pen-shaped tower, I smelled a familiar scent, or really two familiar scents mixed together. The first was the scent of the sea, a strong and briny smell that still came from the seaweed of the Clusterous Forest when the wind was blowing in the direction of Stain’d-by-the-Sea. The second scent took me a moment to identify. It smelled in a certain way that was on the tip of my tongue until I breathed it in one more time.

“Lemony,” I said, but I was not saying my name out loud. I took the piece of paper over to the bed stand, turned on the reading light, and waited a minute or two for the lightbulb to get good and hot. While I waited I looked around the room, and it occurred to me that Zada and Zora were wrong. The Knight girl had started packing. She often stayed up all night in her bedroom working on scientific experiments, but there was not one piece of scientific equipment to be seen. At last the bulb was warm enough.

There are three things to know about invisible ink. The first is that most recipes for it involve lemon juice. The second is that the invisible ink becomes visible when the paper is exposed to something hot, such as a candle or a lightbulb that has been on for a few minutes. I held the paper up, very close to the lightbulb, and watched. Zada and Zora saw what I was doing and walked over to get a look. Dr Flammarion also stepped closer. Only Theodora did not watch the paper as it warmed up, and instead took a blouse from the closet and held it up to her own body to look at herself in the mirror.

No matter how many slow and complicated mysteries I encounter in my life, I still hope that one day a slow and complicated mystery will be solved quickly and simply. An associate of mine calls this feeling “the triumph of hope over experience,” which simply means that it’s never going to happen, and that is what happened then. The third thing to know about invisible ink is that it hardly ever works. After several minutes of exposing the paper to heat, I looked at it and read what it had to say: