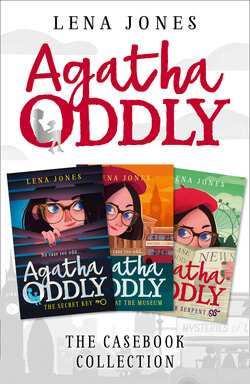

Читать книгу The Agatha Oddly Casebook Collection: The Secret Key, Murder at the Museum and The Silver Serpent - Lena Jones - Страница 10

Оглавление

I’ve just finished liquidising a pile of vegetables when Dad walks into the kitchen, begrimed with mud and smelling of manure. I’d forgotten my tiredness in the excitement of making something new.

‘What on earth are you doing, Aggie?’

‘Making dinner,’ I say.

‘With all the green mush, I thought it might be some kind of science experiment,’ he laughs.

I sigh – Dad can be soooo closed-minded sometimes. He isn’t a bad cook, but he isn’t a very good one, either. I often make dinner for the two of us, but it’s usually one of his favourites – something easy, like sausages and mash or beans on toast. Who can blame me for wanting to try something different for a change? I’d found a dog-eared copy of Escoffier’s Le Guide Culinaire from a bookshop on the Charing Cross Road, and then spent an evening trying to decode his instructions from the original French. Dad looks over at the wreckage, shaking his head, and trudges off to get clean.

Dad – Rufus to everyone but me – has been a Royal Park warden since he left school at sixteen. He’s worked his way up to the position of head warden of Hyde Park, so we live in Groundskeeper’s Cottage. Still, even though Dad’s in charge, he refuses to let others do all the dirty work and is never happier than when he’s got his sleeves rolled up and is getting his hands dirty. He reappears in a fresh shirt, smelling strongly of coal-tar soap, which is an improvement from the manure. He looks over at the food I’m making, stroking his gingery-blond beard.

‘What … is it?’

‘Vegetable mousse, with fillets of trout, decked with prawns and chopped chervil.’

‘Looks quite fancy, love.’

‘Just try it – you’ll never know if you like it otherwise.’

Dad shrugs and sits down.

I’ve been saving up for weeks for the ingredients. Dad gives me pocket money in exchange for a couple of hours shovelling compost at the weekend so it’s been a hard earn. But it’s worth it – everyone should have a chance to try the better things in life, shouldn’t they? Dad reaches for his fork, staring at the plate. He searches for something diplomatic to say, and fails. ‘It’s not very English.’

I smile.

‘Poirot says something like, “the English do not have a cuisine, they only have the food,”’ I recalled.

He groans at the mention of my favourite detective. I go on about Hercule Poirot so much that Agatha Christie’s great detective is a bit of a sore spot for Dad.

‘You and those books, Agatha! Not everything that Poirot says is gospel, you know.’

I ignore this last comment and plonk a plate of the fish and veg medley in front of him. He takes a fork of everything, and I do the same.

‘Bon appetit!’ I smile, and we eat together.

Something is wrong. Something is very wrong.

I look to Dad, and I’m impressed by how long he manages to keep a straight face.

Something awful is happening to my taste buds. I can’t bring myself to swallow for a long moment, and then I force it down, gagging.

‘I may have … mistranslated.’

Dad swallows, eyes watering.

‘Might I have a glass of water, please?’

When the last of the mousse has been scraped into the bin, we go off to buy fish and chips. I decide not to paraphrase Poirot’s thoughts on fish and chips, that ‘when it is cold and dark and there is nothing else to eat, it is passable’. I don’t think Dad would be amused and, besides, I really like fish and chips.

After carrying them back from the shop in their paper parcels, our stomachs rumbling, we eat in happy silence. I savour the crisp batter, the soft flakes of fish, the salty, comforting chips. For once, I have to admit that Poirot might have been wrong about something.

While we eat, Dad asks about my day, but I don’t feel like talking about school and the CCs, or the headmaster, or about how I’d zoned out in chemistry class, so I ask about his instead.

‘So are the mixed borders doing well this year?’

‘Not bad,’ he grunts.

I think of the book I’m reading at the moment.

‘And do you grow digitalis?’

‘If you mean foxgloves, then there are patches of them down by the Serpentine Bridge.’

‘What about aconitum?’ I eat a chip, not looking Dad in the eye.

‘Monkshood? You know a lot of Latin names … Yes, I think there’s some in the meadow, but I wouldn’t cultivate it. It’s good for the bees, though.’

‘Ah … what about belladonna?’

‘Belladonna …’ His face darkens, making a connection. ‘Foxglove, aconitum, belladonna … Agatha, are you only interested in poisonous plants?’

I blush a little. Found out! Poisonous Plants of the British Isles is sitting in my school satchel as we speak.

‘I’m just curious.’ Deep breath.

‘I know that, love, I do. But I worry about you sometimes. I worry about this … morbid fascination. I worry that you’re not living in the real world.’

I sigh – this is not a new discussion. Dad loves to talk about the REAL WORLD, as though it’s a place I’ve never been to. Dad worries that I’m a fantasist – that I’m only interested in books about violence and murder. He’s right, of course.

‘I’ll do the washing-up,’ I say, quickly changing the subject. Then I look over at the sieves, pans and countless bowls that I’ve used in my culinary disaster. Perhaps not.

‘My turn, Agatha,’ says Dad. ‘You get an early night – you look tired.’

‘Thanks.’ I hug him, smelling coal-tar soap and his ironed shirt, then run up the stairs to bed.

When we’d first moved into Groundskeeper’s Cottage, I chose the attic for my bedroom. Mum had said it was the perfect room for me – somewhere high up, where I could be the lookout. Like a crow’s nest on a ship. I was only six then, and Mum had still been alive. Before that, we’d squeezed into a tiny flat in North London, and Dad had ridden his bike down to Hyde Park every day. He’d been a junior gardener when I’d been born, still learning how to do his job. The little flat was always full of green things – tomato plants on the windowsills, orchids in the bathroom among the bottles of shower gel and shampoo …

The attic has a sloping ceiling and a skylight that is right above my bed so, on a clear night, I can see the stars. Sometimes I draw their positions on the glass with a white pen – Ursa Major, Orion, the Pleiades – and watch as they shift through the night.

The floorboards are covered with a colourful rug to keep my toes warm on cold mornings. We don’t have central heating, and the house is draughty, but in mid-July it’s always warm. It’s been scorching today, so I go up on my tiptoes and open the skylight to let some cool air in. My clothes hang on two freestanding rails. Dad is saving to get me a proper wardrobe, but I quite like having my clothes on display.

On one wall there’s a Breakfast at Tiffany’s poster with Audrey Hepburn posing in her black dress. Next to her is the model Lulu. There’s also a large photo of Agatha Christie hanging over my bed, which Liam gave me for my birthday. On the other is a map of London … Everything I need to look at.

My room isn’t messy. At least, I don’t think it is, even if Dad disagrees. It’s simply that I have a lot of things, and not much room to fit them in. So the room is cluttered with vinyl records, with books, with a porcelain bust of Queen Victoria that I found in a skip. Every so often, Dad makes me clear it up.

And so, I try to tidy now. But with so little space it just looks like the room has been stirred with a giant spoon.

I take the heavy copy of Le Guide Culinaire and place it on my bookshelf, which takes up one wall of the room. I sigh – what a waste of time. What a waste of a day.

I run my hand along the spines of the green and gold-embossed editions – the mysteries of Poirot, Miss Marple, and Tommy and Tuppence – the complete works of Agatha Christie, who my mum named me after. She’d got me to read them because I liked solving puzzles, but said I should think about real puzzles, not just word searches and numbers. When I’d asked what she meant, she had said –

‘Everybody is a puzzle, Agatha. Everyone in the street has their own story, their own reasons for being the way they are, their own secrets. Those are the really important puzzles.’

I feel hot tears prick the back of my eyes at the thought that she’s not actually here any more.

‘I got called in front of the headmaster today …’ I say out loud. ‘But it was OK – he just let me off with a warning.’ I continue, tidying up some clothes. I do this sometimes. Tell Mum about my day.

I change from my school uniform into my pyjamas, hanging everything on the rails and placing my red beret in its box. What to wear tomorrow? I choose a silk scarf of Mum’s, a beautiful red floral Chinese one. I love pairing Mum’s old clothes with items I’ve picked up at jumble sales and charity shops, though some of them are too precious to wear out of the house.

Next, I go over to my desk in the corner and unearth my laptop, which is buried under a pile of clothes. I switch it on and log in. People at school think I don’t use social media, but I do. I might read a paper copy of The Times instead of scrolling down my phone, and write my notes with a pen. But I’m more interested in technology than they’d know. You can find out so much about people by looking at what they put online. Of course, I don’t have a profile under my own name. No – online, my name is Felicity Lemon.

Nobody seems to have noticed that Felicity isn’t real. Several people from school have accepted my friend requests, including all three of the CCs. None of them have realised that ‘Felicity Lemon’ is the name of Hercule Poirot’s secretary, or that my profile photo is a 1960s snap of French singer Françoise Hardy.

I scroll through Felicity’s feed, which seems to be endless pictures of Sarah Rathbone, Ruth Masters and Brianna Pike. They must have flown out to somewhere in Europe for a mini-break over half-term. They pose on sunloungers, dangle their feet in a hotel swimming pool and sit on the prow of a boat, hair blowing behind them like a shampoo commercial. Despite myself, I feel a twinge of jealousy and put the lid down.

Rummaging through my satchel, I take out the notebook that I started earlier in the day. I put it by my bed with my fountain pen, in case inspiration strikes in the night – that’s what a good detective does: they note down everything, because they never know what tiny detail might be the key to cracking a case.

Most of my notebooks have a black cover, but some of them are red – these are the ones about Mum – all twenty-two of them. They have their own place on a high shelf. My notes are in-depth – from where she used to get her hair cut to who she mixed with at the neighbourhood allotments. Every little detail. I don’t want to forget a single thing.

I look over at Mum’s picture in its frame on my bedside table. She’s balanced on her bike, half smiling, one foot on the ground. She’s wearing big sunglasses, a crêpe skirt, a floppy hat and a kind smile. There’s a stack of books strapped to the bike above the back wheel. The police had blamed the books for her losing control of her bike that day – but Mum always had a pile of books like that. I don’t believe that was the real cause of her accident. That’s not why Mum died. Something else had to be the reason.

I climb into bed and pull the sheet over me, then take a last look at the photograph.

A lump rises in my throat. ‘Night, Mum,’ I say, as I turn out the light.