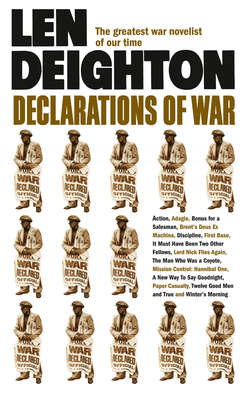

Читать книгу Declarations of War - Len Deighton - Страница 7

It Must Have Been Two Other Fellows

ОглавлениеJames Sidney Pelling was fifty-nine years old. Ever since his cadet days he had been obsessed with motor-cars. He now had four: a brand-new Bentley, a battered DB6, a Land-Rover for the farm and a Cooper S that his new blower and modified carburettors would convert into the most exciting car of all.

For a job as complex as this he needed the electronic tuning bench at the Hillside Garage. They were Colonel Pelling’s tenants – he owned all the land between the farm and the Salisbury road – and the owners gave him the use of the work-shop on Sundays.

On this particular Sunday, cook had sent him sandwiches and a Thermos of coffee. He’d hardly touched them, working right through lunchtime. By three in the afternoon he was almost finished and was watching the timing on the neon strobe when a car bumped over the rubber strips that rang a bell in the office. Pelling ignored it. Anyone who failed to see the huge CLOSED notice on the pumps shouldn’t be permitted behind the wheel of a car, in Pelling’s opinion. There was the imperious toot-de-toot of an Italian power horn. It sounded again, and Pelling decided that the driver must be told to go away. He wiped his hands on a piece of cotton waste.

As he entered the cashier’s glass-fronted box, he noticed that it was raining heavily. He reached for the ancient raincoat and hat that were kept behind the door and buttoned the torn collar tight around his throat.

He could always distinguish a salesman’s car: new, cheap and fast, well-worn by heavy driving and scratched from careless parking. The driver had an expense-account plumpness. He sat behind the wheel in a drip-dry shirt, while the jacket of his shiny Dacron-mixture suit was on a hanger in the rear window. It was still swinging gently from the abrupt braking.

‘Come on, Dad,’ said the driver with a sigh.

Before Pelling could think of a reply the man was out of the car and advancing upon him, smiling the smile that only successful salesmen produce so quickly. ‘Colonel Pelling,’ he said. ‘Colonel Pelling. Well, I’ll be buggered, begging your pardon, sir.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Pelling stiffly. ‘You have the advantage of me…’

‘Wool. You can’t go wrong with me next to the skin.’ He laughed.

‘Wool?’

‘My little joke, Colonel.’ He stood to attention in a burlesque of military obedience. ‘Wool; W-o-o-l, Corporal Wool 397, sir! Royal Welsh Greys, D Squadron, No. 1 Troop. From Tunisia all the way to Florence. Best years of my life, in a way. Place me now, sir?’

Pelling tried to make this over-fed, middle-aged man into a young corporal. He failed.

‘The farmhouse on the hill,’ prompted Wool, ‘near Sergeant-Major village.’

The Colonel still looked puzzled and Wool said, ‘Oh well, it must have been two other fellows, eh?’ He laughed and repeated his joke slowly. When he spoke again his voice was loud and a little exasperated. ‘Don’t tell me you’ve forgotten the farmhouse. When the Tedeschi nearly clobbered the whole mob of us, and we sat there like lemons?’

‘Of course,’ said Pelling, ‘you were the fellow with the Bren. I remember him quite differently…’

‘No, no, no,’ said Wool. ‘That was a bloke named Stephens. He got the M.M. for that. That was the following week.’

‘Corporal Wool, yes…’

‘Lance-jack at the time, actually. Ended up a sergeant though: temporary, acting, unpaid.’ He smiled and saluted.

‘Wool,’ said Pelling. ‘It’s good to see you again. You’re looking well and prosperous.’

Wool grinned and tucked his shirt into his waistband. ‘It always comes loose when I’m driving. Yeah, well, I’m not bad, how are you?’

‘I’m well, in fact very well.’

Wool shook his head doubtfully and stared into Pelling’s face. ‘You’re not looking too good, Colonel, if you don’t mind an exlance-jack saying so.’

‘I’m just a bit tired,’ said Pelling. He smiled at Wool’s concern. ‘I’ve been working since eight o’clock this morning.’

‘Here?’

‘Yes.’

‘Christ!’ He looked around the rain-swept forecourt. It was grimy and littered with ice-cream tubs. A sign said: FREE WITH 4 GALLONS OF PETROL, A PACKET OF BALLOONS.

‘A packet of bleeding balloons,’ said Wool. ‘All these petrol companies are the same: free bloody hair-brushes or free bloody wine-glasses. What they want to offer is a free bloody service: top-up the battery, check the water and tyre pressures. I’ll bet you never wipe the windscreens, do you?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Exactly. Here,’ he grabbed at Pelling’s sleeve, ‘you own this place?’

‘I’m afraid not.’

Wool sniffed and nodded to himself. ‘It’s a rotten shame, that’s all I can say. You were the youngest-looking Colonel any of us had ever seen – a chestful of gongs, and a good bringing-up, it’s a bloody disgrace. There’s your Socialist governments for you. Here, I’m getting wet, jump in out of this rain.’ Wool reached for The Times and put two sheets of it upon the plastic seat before opening the door for Pelling.

‘Colonel Pelling,’ said Wool, looking at him closely and imprinting the memory of this moment upon his mind. ‘Colonel Pelling.’

Wool twisted round in his seat and found a packet of cheroots in his jacket. He tore off its cellophane wrapping and opened it with a flourish. ‘Have a cigar?’

‘Thank you, Wool, no. I’ve given up smoking.’

‘It’s a rich man’s hobby now,’ agreed Wool. He put the cheroots away and took from the glove compartment a Havana in a metal container. He used a cigar-cutter to prepare it, and lit it with enough ceremony to demonstrate that he was a man familiar with good living. He exhaled the smoke slowly and turned to face the ex-Colonel with a calm happiness.

The Colonel had aged well; no surplus fat or heavy jowls. His nose was bony and his jaw was hard. He was lean and tall, just as Wool remembered him, except that the hair below his oily hat was almost white. Wool looked at Pelling’s hands. His dirty skin was tanned and leathery, just as one would expect of a man who spent long hours out in all weathers slaving at the petrol pumps.

Wool, on the other hand, was not so easy to identify with the nineteen-year-old Corporal that the Colonel had briefly known. Florid, and wearing large fashionable black-framed spectacles, he was like any one of the dozens of commercials who filled up at the Hillside before the non-stop race back to London. On his finger there was a signet ring and on his wrist a complex watch and a gold identity bracelet.

It must have been two other fellows, thought Pelling. Yes, as soldiers they had been saints or hooligans, torturers or rescuers, but none survived. Those that eventually became civilians were different men.

Pelling looked at the interior of the car. No doubt about it being cherished and cared for, even if it wasn’t done to Pelling’s taste. The steering-wheel had a leather cover, the seats were covered in imitation leopard-skin and a baby’s shoe dangled from the mirror. There was a St Christopher bolted to the dashboard and in the rear window there was a large plastic dog that nodded and two cushions with the registration number boldly knitted into their design.

‘Seen any of your blokes?’ asked Wool.

‘Not recently,’ said Pelling.

‘I’ve never been to an Old Comrades or anything.’

‘Nor have I,’ said Pelling. ‘I’m not much use at that sort of thing.’

Wool looked at the filthy raincoat. ‘I understand,’ he said. He studied the ash of his cigar. ‘The funny thing was that you only came up to the farmhouse for a look-see, didn’t you?’

‘I’m only here for a shufti, Lieutenant.’ The subaltern looked at the man crawling in through the door. The newcomer’s rank badges were unmistakable, and yet he looked younger than the thirty-year-old Lieutenant. ‘You came on foot, sir?’

‘Jeeped up the wadi.’

‘Corporal. Crawl out and move the Colonel’s Jeep into the barn out of sight.’

‘There’s eight gallons of water in it for you,’ said Pelling, ‘and a crate of beer for your chaps.’

‘That will cheer them up, sir.’

‘It won’t cheer them up much,’ said Pelling. ‘It’s that gnats’-pee from Tunis. Psychological warfare by the temperance people, I’d say.’

The Lieutenant rubbed his unshaven chin and nodded his thanks as the Corporal went out into the yard and started to move the Jeep.

‘It’s stupid of me,’ said Pelling. ‘I didn’t realize they could see as far as the track.’

‘They’ve got a new O.P. on the east slope of the big tit – Point 401 that is – we only noticed it yesterday, my sergeant saw a bit of movement there. Can’t be sure it’s manned all the time.’

‘It was stupid of me,’ repeated Pelling.

The Lieutenant had seldom spoken with colonels and certainly not one who’d admit to stupidity. Awkwardly he said, ‘Would you like to go up to the loft, sir? Sloan, get brewing. And open that tin of milk.’

The Colonel held the field glasses delicately, as though he was taking the pulse of two black-metal wrists. From the loft he could see more than ten miles along the valley. It was noon. The sunbaked hills were misty green puddings, surmounted by outcrops of grey rock and ringed by precarious terraces of crops. The olive groves lower down were plagued with the black festering sores of artillery fire, and untended vegetables had run to seed. Nowhere was there any movement of man or machine, nor were there horses or mules, cattle, sheep or goats – at least, no live ones. Pelling searched carefully along the German lines from where the River Caro was no more than a piddle of dirty water meandering through the high-banked wadi, to the ruins of ‘Sergeant-Major’, as the troops had renamed the village of Santa Maria Maggiore. If it hadn’t been for the cowshed at the far end of the yard, and the abandoned Churchill tank fifty yards behind it, he’d have been able to see the hills beyond the river, and the main road that led eventually to Rome. He studied the road carefully: dust hung above it like incense smoke, and yet he could see no transport there. From somewhere far away a church bell began tolling an inexpert rhythm.

‘A dedicated priest,’ said Pelling, still looking through the glasses. Then he lowered them and began to wipe the lenses. He used a white linen handkerchief, rough-dried and unpressed and mottled with the faint stains of ancient dirt.

‘Partisans, more likely. They use the bells as signals to regroup.’ He passed the Colonel a handkerchief of khaki silk. Bought by a loving mother for a newly commissioned son, thought Pelling as he finished polishing the binoculars. Handling the smelly glasses with exaggerated care, Pelling put them into the battered leather case and gave them back to the Lieutenant.

‘Your people will be coming tomorrow, sir?’

‘Yes, we’ll get rid of that tank and cowshed for you.’ He said it like a surgeon about to amputate, and like a humane surgeon he tried to give the impression that it would make things better.

‘That will give us quite a view,’ said the Lieutenant. Pelling nodded. They both knew that it would make the farm such a good observation point that then the Germans would also want it. Very badly.

‘Our attack can’t be far off now,’ said the Lieutenant, seeking reassurance. Pelling said nothing. Allied H.Q. didn’t tell engineer colonels their plans, any more than they told infantry subalterns. They told the one to clear fields of fire and the other to shoot.

Pelling said, ‘In another three or four weeks the autumn rains will make that valley into a bog. Do you know what rain does to that dusty soil?’ It was a rhetorical question; the Lieutenant’s face, hair, hands and uniform – like everyone else’s – were coloured grey by the same abrasive powder that got in the guns and the tea.

‘Yes,’ said the Lieutenant. The attack would be soon.

What sort of man would build a farm up here on the side of Monte Nuovo: a fool or an aesthete, or both. The wind screamed constantly, the cloud was almost close enough to touch and the trees were stunted and hunchbacked; but the view was like a Francesca painting. Back in Pelling’s part of the world men built their houses low.

In war, though, it was the villages in the valleys that survived best. Houses and churches on high ground were invariably destroyed as the armies fought for observation points. There was a moral there somewhere, thought Pelling, but he was too tired to deduce it.

‘What will you do after the war, Lieutenant?’ Pelling sipped the hot sweet tea that was heavy with the smell of condensed milk.

‘Oh, I don’t know.’ This was a new sort of conversation and he spoke in a different voice and omitted the ‘sir’. ‘I always wanted to be a vet – I’m keen on animals – but I’ll be too old to start studying by the time this lot’s over. Probably I’ll just take over the old man’s antique shop. And you?’

At first the Lieutenant was afraid that he’d offended the young Colonel. With an M.C. and D.S.O. and a colonel’s rank at his age, perhaps he felt that there was no other world but the army. To soften it a little the Lieutenant said, ‘You’re a regular, of course.’

Pelling grinned, ‘Yes. Woolwich, Staff College, the lot. I’m about as regular as you can get.’

‘I suppose this is…to us it’s the worst sort of interruption to our lives, but I suppose for you it’s the thing you’ve been waiting for.’

‘All you War Service types think that,’ said Pelling, ‘but if you think that any regular soldier likes fighting wars, you’re quite wrong.’ He saw the Lieutenant glance at his badges. ‘Oh, we get promotion, but only at the expense of having our nice little club invaded by a lot of amateurs who don’t want to be there. The peacetime army is quite a different show. A chap doesn’t go into that in the hope that there will eventually be a war.’

‘No, I suppose not.’

‘You won’t believe it,’ said Pelling, ‘but peacetime soldiering can be good fun, especially for a youngster straight from school. The army’s so small that one gets to know everyone. One travels a lot, and there’s ample leave as well as polo, cricket and rugger. It’s not at all bad, Lieutenant, believe me. Even the parade ground can have a curious satisfaction.’

‘The parade ground?’

‘A thousand men, perfectly still and silent…and able to move in precise unison. Professional dancers probably share the same elation.’

‘Like marching behind a military band? We did that once, passing out of OCTU.’

‘That’s a part of it, but for me a silent parade ground has even more of a ritualistic effect. The body moves and yet the mind remains. There is a separation of physical and spiritual self that can liberate the mind like nothing else I know.’

‘Are you a Buddhist, sir?’ It was a reckless guess.

‘Once I nearly was,’ admitted Pelling.

‘And now?’

‘I am slowly rediscovering Christianity.’

Pelling had told no one about the time he’d spent billeted in the monastery near Naples, of the long conversations he’d had with the Abbot, arguing so fiercely that at times they were both yelling. Apart from his driver no one knew of the trips to the slum villages, and not even the driver could have guessed the effect that time had had upon him. ‘I’m going into a monastery,’ said Pelling.

‘Really?’ He stared at the Colonel, trying to see some strange secret.

Pelling nodded. He did not doubt that he would go back to the great white building with its orchards and its library and the life that went on without interruption for century after century. It was arranged that he would get both the tractors going again and find or build a lorry that would take the produce into Naples where they would get a better price for their vegetables.

There had been times during the fighting when only the promise of a cloistered life kept Colonel James Pelling going. He visualized himself thirty years hence; stouter than Father Franco and quieter than Father Mario – and perhaps less devout than either. Yet, as the old man had explained, the Order had in the past received men with doubts, and some of these had become its most valuable sons. Would one ever get used to being called ‘Father James’, Pelling wondered.

‘Do you believe there is a heaven for tractors, Father James?’

‘If there isn’t, Brother, then Father James will not go there.’ They were truly good, those simple men.

‘Would you be able to stand that?’ It was the Lieutenant speaking. ‘The quiet: I’d go bonkers.’

‘It’s not a silent Order,’ said Pelling.

‘You’ve no family then?’

‘A father.’ He’d go – what was the word the Lieutenant had used? – bonkers. Yes, he’d go bonkers all right. But Pelling was determined not to repeat the mistakes of his father’s solitary life. Days in the boat yard or at the drawing-board, lunch in the pub with the works manager. Dinner in the yacht club, or a late snack left by cook: dry ham sandwiches clamped under a plate. And what was the purpose of his father’s life: a couple of knots gained by hull modifications, a win at Cowes, a telegram from a transatlantic cup winner. That wasn’t enough for him, not nearly enough. Pelling could hear the soldiers below talking about what they would do with their lives after the war.

‘Mr Steeple, sir.’ It was Wool’s voice calling softly, ‘Two Mark IVs turning off the road near the track at two o’clock.’

Lieutenant Steeple said, ‘Sergeant Manley, get your sniper’s rifle. Have a go at their visors. You never know, you might star his periscope glass.’

The Lieutenant was too late grabbing for the glasses. ‘They’ve stopped,’ grunted Pelling. He rubbed the lenses with a handkerchief and then looked again. ‘Nice hull-down position if they were going to batter us.’ Their guns hadn’t traversed, so it was difficult to know whether they were covering the main road or the farmhouse to the east of it. The Lieutenant picked pieces of straw from his duty battle-dress blouse while he waited for the next move.

‘You should wear denims,’ said Pelling without taking the glasses from his eyes. ‘That rough battle-dress material picks up straw and stuff.’ He couldn’t see very well, for the morning sun reflected on the dry, dusty soil so that it shimmered as he remembered the desert had done.

‘No, no, no, sir,’ interrupted Wool. He chuckled and flicked ash from his cigar. ‘It wasn’t hot and sunny, it was a close overcast day. There had been rain that morning. Not the sort of rain we got a few weeks later, but rain. And it wasn’t morning, it was late afternoon when the German tanks arrived, very late, almost dark. You were in the cellar drinking tea with that Mr Steeple, the officer. I came down the cellar steps and said, “Any more tea for anyone? There are a couple of Tedeschi tanks outside the front door.”’

‘Damn!’ shouted Steeple. Pelling looked around for a place to stand his mug of tea and then decided to drink it hurriedly. It scalded his mouth. Pelling let Steeple up the steps first. It was his show, but Pelling couldn’t resist interfering.

‘Radio?’ called Pelling.

‘Bishop!’ yelled Steeple. ‘Tell Company: Two Ted Mark IVs moving in on us fast.’ He looked at Pelling and said more calmly, ‘No, wait a minute, make that: Two Mark IVs, range nine hundred, bearing oh three five.’

Everyone stood very quietly listening to the radio operator patiently repeating the message. Only Pelling and Steeple could see the two enemy tanks. The others were just staring very hard at the wall and the rafters, as if by opening their eyes wide they would be able to hear better. It must have been three or four minutes before anyone spoke and then Wool said, ‘Listen to that nightingale sing! It’s as clear as a glass of Worthington…’

‘Couldn’t have been me,’ chuckled Wool. ‘I couldn’t tell a nightingale from a budgerigar; still can’t.’ He puffed his cigar. ‘What I do remember, though, is you making us black our faces with soot from the stove. Regular Sioux war party we looked.’

Wool had often played Red Indians when he stayed with his Gran. Blacking his face was an important part of that. He’d take his uncle’s boat and row along the stream. Using the oar against the river-bed, he could push himself right in among the reeds so that he and the boat disappeared. The cars on the road to Bishopsbridge were stage coaches, but pedestrians were miners and no honourable Indian brave would scalp them.

‘Did I?’ said Pelling.

‘Yes, it was after the rations came up that night. You nearly put Bishop on a charge when he said the soot would make no difference in the dark. You called him a young lout, I remember. He was a family man, too. He was real choked about that.’

‘None of them were louts,’ said Pelling. ‘They were good chaps.’

‘But that Keats was a dodgy one. He’d done three years for duffing up a policeman at a Cup Final in 1936. Sergeant Manley was a bit nervous of Keats. Never gave him any dirty jobs or anything dangerous.’

‘Was Keats the Scots lad that tried to get back along the ditch?’

‘That’s him; short thickset bloke with bad teeth.’

‘It was a brave thing to do.’

‘Brave?’ said Wool. ‘He was trying to give himself up to old Ted. He was off to surrender, thought he was going to get killed.’

‘You think so?’

Keats put his rifle to rest against the broken stove and then crouched by the window waiting for a break in the mortar fire. He went over the windowsill so skilfully that few men saw him go.

Like a burglar, reflected Pelling, yes, like a burglar.

‘Rifle grenades, not mortars,’ said Wool. ‘You taught me the different sound of those. Like a champagne cork popping, the two-inch mortar, you said. Mind you, I’d never heard a bottle of champers pop at that time.’ He laughed to remember his youth. ‘And it was a Sherman tank, not a Churchill.’

‘What makes you think that Keats was trying to surrender?’

‘He was carrying a piece of bed-sheet. It was tucked into the front of his blouse. When the burial party got up to him next day they thought he must be an old one – you know, swollen up with the sun – but it was a sheet.’

‘Poor fellow.’

‘Yes. Kept us going all night, didn’t he. Screaming and carrying on. Mona or Rhona or something. He was probably only nicked at first, if he’d kept quiet he would have been all right perhaps. Stephens tried to shoot him once, you know. It was too dark.’

Why had Wool chosen to remember it like that? Had the new fashion in embittered war films and stories persuaded Wool to distort the reality of his memory in favour of the more fashionable rubbish of writers who had not been there? Wool had been a hero: young, pimply, foolish and brave.

‘I’d like to have a go,’ said Wool.

‘It’s up to the Colonel,’ said Lieutenant Steeple. No one had to ask what Wool was volunteering for.

‘By all means,’ said Pelling. Already the valleys were dark, and the last glimmer of sunlight lit the church on the mountaincrest facing them.

‘I’ll go out the front,’ said Wool. ‘That’s where they’ll least expect me. I’ll make towards the Sherman in front of us and then work round to the track, keeping well away from the house. I’ll see if I can spot Keats, too.’

Lieutenant Steeple said, ‘Sergeant Manley, we’ll put some phosphorus grenades into the wadi end of the track. Make a rumpus while the Corporal gets clear.’ To Wool he added, ‘Keats is probably done for, don’t take any risks to bring him back.’

Pelling said, ‘Corporal, if you are spotted, lie low. We’ll tickle them up to give you a chance. If you need to come back to us, come in on a line with the barn. We’ll be extra careful on that bearing.’

The dark was like playing Red Indians, too. He’d crept up on the bison in Mr Jones’s field. Sometimes he’d be within touching distance before it ran away bleating. When he got out of the army he’d go back to Gran’s. He liked it in the country; Bell Street was a dirty place, without grass or trees or anywhere that kids could play. When he had kids they would have the countryside to play in. They’d row out into the reeds, as he had done, and catch fish and help old Mr Jones herd the Jerseys and carry the milk.

Hold it, there’s the tank right ahead. A Sherman Firefly with Cindy Four painted on it in red letters, that’s the one. It was just like being a Red Indian, except that the ground was cold and damp and the cowboys were using two-inch mortars and Mark IVs. His bloody knee! There was a stink of ancient dung and fresh human excreta, but the wet grass had a smell that he liked. Careful of the wire.

What sort of job could he get in the country? None that would bring much money, but then one didn’t need so much money in the country. Gran would let him have the room in the loft and there’d be agricultural training courses for ex-servicemen. He’d asked the Education Officer. Now that he knew Wool was serious he’d promised to get the papers about it from Division.

‘Did you ever think about one of those security organizations?’ said Wool. ‘Still, you’re not as fast on your pins as you used to be. They’d probably not want a bloke as old as you are. You might prove a bit of a liability up against a gang of toughs using ammonia and pickaxe handles.’

‘That’s true,’ said Pelling.

‘The trouble is,’ said Wool, ‘a colonel: what training has he got for civvy street? I mean, I was a driver. I remustered from infantry. I could find my way around an engine, too, at one time. Nowadays, of course, least little thing and she goes back into the garage. The firm pay all the repair bills. But coming out a sergeant with my mechanical skill made me a more desirable employee than you.’

‘Very likely,’ said Pelling.

‘After all, you were just pointing at maps and giving orders. We were the people who actually did the work.’

‘That’s true.’

‘It is true, isn’t it? See, and in peacetime your good wages goes to chaps who do the real work.’ He heaved himself round in his seat and from a large carton in the rear seat he brought a Munchy bar and unwrapped it.

‘Like us?’ supplied Pelling.

Failing to find irony in Pelling’s impassive face, Wool broke the Munchy into four large pieces and offered the open wrapper to Pelling, who declined. Pelling knew that there would be cold meat and pickles waiting on the sideboard. Vaguely, he wondered what was on TV.

‘Ever go back to Italy?’ Wool asked.

‘Never,’ said Pelling.

‘Don’t like the Eyeties, eh? Yeah, I understand. I went back a couple of times. Package tour, very nice. Six cities in eighteen days. Just enough time to see the sights, not long enough to get bored. Course, I like the Eyetie food,’ he patted his stomach. ‘Perhaps it’s too oily for you, but I eat a lot of it: fettuccine alla panna, osso bucco, lasagne al forno. I’m quite an expert on the old cuisine Italiano. Mind you, you have to watch them with the women, they’ve got no respect for womanhood. My eldest was pestered by some waiter-type in Florence, but I didn’t have no nonsense. I reported him to the management and said I was a director of the firm that runs the tours – I’m not of course – and they sacked him.’

At least he went back, thought Pelling, he didn’t start four letters and finish none of them.

Pelling said, ‘So when you went out that night, you weren’t primarily trying to get the wounded fellow – Keats – back to the farmhouse?’

‘Your memory,’ said Wool. He chuckled. ‘It must be even worse than mine. No, the Lieutenant was right. That M.G. 42 had sliced old Keats up good and proper. The way I saw it, they probably had him in their sights, waiting for some medal-hungry twit to walk into them. I didn’t want to go near him.’

For the first time Pelling was clearly able to recall the young Corporal who had been with them that day and night. But everything about Wool had changed: his build, face, voice and demeanour. The Corporal had been a wiry fellow with a shy smile, a red face and a thin London accent. Wool finished his Munchy, burped, loosened his belt and reached for a jacket hanging behind him.

‘Look at this, Colonel.’ He delved into his wallet, pulling out paper money and various business cards and stuffing them back with tuts of irritation until he found what he was looking for: a photo. ‘That’s what I’ve done for myself. I may not have been an officer but that’s what I’ve done for myself.’

Pelling expected a photo of wife and family, but it was a photo of a house. Close behind it there were many others. ‘Nineteen thousand,’ said Wool. ‘Probably worth twenty-five by now. My old Gran left me her little house in the country. But it was a dead-and-alive little hole, so I sold it for nine hundred and had enough to put down on a bungalow in Morden. Do you know South London at all?’

‘No.’

‘It’s a very nice place where we live: doctors and that live there, well-to-do people. It’s so convenient to London, you see.’ While he was talking he’d sorted through his wallet and found another photo. He showed it to Pelling. Six young men, tanned and smiling, stood arms interlinked in the blazing African sun.

‘You were a different fellow then,’ said Pelling.

‘I was a little twit,’ said Wool bitterly, as though he hated the man that he saw in the photo. ‘Yes sir no sir three bags full sir. Creeping around, apologizing for being alive.’

‘That’s not how I remember you,’ said Pelling. ‘You were full of life, laughing and joking. And you were full of ideas too.’

‘Was I?’ said Wool. He could not remember the terrain or the tactical situation in the way that the thirty-year-old Pelling had remembered. Wool’s memories were simpler: the cold corned beef that he didn’t eat; Keats, the squint-eyed little Scottish private with the wrist-watch he’d taken from a dead German Grenadier; and the posh Lieutenant who pronounced Tedeschi so perfectly that Wool had imitated it ever since.

It made no difference which of them was assigned to guard duty, for they all sprawled on the floor near the windows. They ate their cold rations where they sat and passed their cigarettes from hand to hand, leaving their positions only to use the latrine pit twenty paces across the back yard.

‘That’s wealth, that farmland,’ said a private soldier named Stephens. He jerked his head towards the smashed window. Before the war he had been a solicitor’s clerk and was duly respected as educated.

‘D’ye not see these Italian farmers with the arse out of their trousers. Do you ken that, Stevie?’

‘Land is wealth,’ repeated Stephens, ‘but not necessarily a sound investment.’

‘Get on!’ said Private Teasdale. ‘Look at the price of a titchy little bottle of olives. About one and threepence, and how many in it? bleeding twenty!’

‘A dozen, more like,’ said Stephens, relieved to move the conversation away from the subject of land, of which he had only a tentative understanding. He stole a glance at the olive plantations on big tit. The hillside was studded with them and Stephens abandoned the task of calculating how many olives might be there.

‘What about gold?’ said Private Keats. ‘Bugger owning a farm! Too much like bloody hard work. What I’d want is a neat little gold mine. Dig up a couple of ounces every week. Just enough to pay the rent and give the old lady something to back her fancy at the dogs. That’s real wealth, gold is.’

‘Wealth is energy,’ said Stephens. ‘You know: power stations, hydroelectric stuff, plant and factories…even muscle power. Wealth is just energy.’

‘If you ask me,’ said Corporal Wool, speaking for the first time in several minutes, ‘wealth is time.’

‘What you mean, Corp?’ said Andrews. The new Corporal had that afternoon helped Andrews bring the water in from the Sapper Colonel’s Jeep without anyone asking him to. You didn’t get many corporals like that, in Andrews’s experience. This one should be cultivated. ‘Time is wealth, like?’

‘It’s the only thing you can’t buy, apart from good health,’ said Wool. ‘I mean, we think we’ve got the worst end of the stick, being up here at the sharp end being shot at, right?’ The others nodded. ‘But you think any of those old generals and that back at Div wouldn’t change places, no hesitation?’

‘Would they?’ said Keats. It was a thrilling concept. One to be toyed with. He hoped that it wouldn’t be exploded too soon.

‘Course they would,’ said Wool. ‘Here we are, fit and well and raring to go, with all our life in front of us. Course they would. Why, any of us could do anything…’

‘Well, not exactly anything,’ modified Stephens, who felt his position as the educated man might be jeopardized by this Corporal.

‘Anybloodything,’ said Wool. ‘Any of us could become generals or millionaires or bloody film bloody stars with the right gumption and a bit of luck.’

‘Get away,’ said Keats scornfully, but not so scornfully as to disturb the dream. Rather he said it to coax more details from the pink-faced Corporal. This fellow could do it, thought Keats. He might become a general or a millionaire or a film star. Or even a centre-forward for Celtic, which was Keats’s personal daydream.

‘I tell you,’ said Wool, ‘time is all you need. Twenty-odd years from now we could all be whatever we decide on.’

‘I’d like to be a centre-forward for Celtic,’ said Keats, believing that an early claim would have more chance of fruition.

Teasdale said, ‘I’d like to have a little grocer’s in Nottingham, near the tobacco factory. Lots of married women work there, they have to buy the food for the old man’s supper on the way home. In the side street for preference, and stay open late on pay night. And sell fags and sweets, too.’

Stephens said, ‘I’d have studied to be a solicitor, but I’m too old now.’

‘You’re not,’ said Wool, ‘honest, Stevie, you’re not too old. That’s what I’m telling you. It’s time that’s wealth. When this lot’s over you’ll have time to be a solicitor. You could end up a judge, even.’

‘And what about you, Corp?’ said Andrews.

‘Oh, me,’ said Wool. ‘I’m lucky in a way. I’ve got my future all waiting for me. My old Gran in the country has got five acres. I’ll get a cow and some pigs and chickens. I won’t make a fortune but I won’t be worrying my guts out trying to make a living either. You become a different sort of person in the country. Everyone does, it’s more natural somehow.’ It was then that Wool raised his eyes for a periodic glance at the horizon. ‘Two Ted Mark IVs turning off the track, near the road two o’clock.’

Wool’s voice alarmed Pelling, just as it had done at the time. ‘You were a cool customer,’ said Pelling. ‘I’ll tell you frankly, I was afraid when that shell hit the loft, but you climbed up there before any of us had recovered our wits. It was some silly joke you made that brought us all back to normal again. And then there was the tank…’

‘I was a twit,’ said Wool, pushing the memory of the loft and its smell of warm blood back into his dark subconscious. ‘Full of crap about esprit de corps, comradeship and loyalty. I’m not like that now, I’ll tell you.’

‘What are you like now?’ asked Pelling flatly.

‘I’m a go-getter. I look after number one and make sure that my expense sheets are countersigned and submitted bloody early. There’s no esprit de corps in the chocolate-bar business.’

‘I shouldn’t have let you go out to the tank,’ said Pelling.

‘How could you have stopped me? I knew it was my last chance before your bloody sappers arrived.’

‘You knew I was going to demolish the tank and the cowshed?’

‘I didn’t know anything about a cowshed, but I knew the salvage crew for Cindy Four had been taken off the roster. It was easy to guess what that meant for Cindy.’

‘Why did you go out to the farm then?’

My bloody knee, that’s the second time. It’s damned dark! This field must be full of Conner cans, and the remains of the corned beef stinks to high heaven. God, what a smell. Why was he here, that was a good question. He had no orders to be risking his neck, in fact he had no permission to be absent from the laager. If he copped it tonight – and the chances were that he would – he’d be posted as a deserter and neither his Mum nor his Gran would get the money. Stop. Still, absolutely still. Ugh! What had he touched: crap? No, it’s all right. It’s only Keats. A swarm of bloated flies buzzed around his face. Angrily he waved them away and, so dozy were they, his hand hit some of them in mid-flight. Poor Keats with half his head missing, you poor old sod. I would have let you play for Celtic, Keats. I would have given half my Gran’s fields to have you play once for Celtic, with me in front of the stand, eh? With a funny hat and rattle. Just that afternoon Keats had said, ‘You know, Corp, you’ve changed my bleeding life in a way. You’re right, I mean anybody can do bleeding anything, Corp.’

Careful; stinging nettles, and beyond them the ditch. Lucky that there’s no moon. The night was cloudless; he could see every star for a million miles, except where a piece of night sky without stars was the Sherman tank. Another pile of cans. Just one tin-can makes a noise like a peal of bells on a night as quiet as this. Listen. He froze quite still. He could hear his blood pulsing.

At his Gran’s the net curtains were floor length. At night the wind made them billow and arch as if a thousand phantoms were climbing through the window, one behind the other. But these were no ghosts. No ghost for Keats, no ghost for any of them.

Bloody hell!

There were voices whispering. Whispering sounds the same in all languages, but that won’t be any of our boys standing out here in the dark on the German side of that Sherman. He put his hand upon the tracks; it was tight and true this side. One foot went on to rubber tyre and the other on to the suspension. Silently he eased open the turret hatch and put one foot down on to the breech of the gun…

‘No, no, no,’ said Pelling. ‘You can’t get away with that rubbish. Talk about hiding under a tank and I might believe you, but climbing into a tank to avoid being seen is like climbing Nelson’s Column to avoid being arrested. Anyway, I timed you that night. You’d only been gone eight minutes before the tank engine started. We were scared stiff, we thought the Mark IVs were returning.’

‘You don’t climb into a tank,’ Wool corrected primly, ‘you mount it. She started first go. Of course, I knew she would. I bet Sergeant Anderson she would. Five bob. He knew I wouldn’t tell a lie about it. Paid up as nice as ninepence when I came back.’ Wool reached behind him for another chocolate bar. Pelling didn’t want any, but Wool bit into it greedily. ‘Can’t keep off them,’ he explained waving the bar in the air. ‘Mind you, they are damned good; butter, eggs and four ounces of full-cream milk in every one. The kids love…’

‘Where did you learn to drive a tank?’

‘Haven’t you been following me, Colonel? I was the tank driver.’

‘The tank driver?’

‘Of Cindy Four. That was mine, that tank. I came out to get her back in, didn’t I?’

‘Tank salvage team?’

‘Tank salvage team,’ Wool repeated in scathing mockery. ‘Those stupid bleeders. Those knacker’s-yard attendants. I was a real tank driver. I was Cindy Four’s driver.’

‘You’d come out to get your tank without permission?’ Pelling’s incredulity as a Colonel was tempered by his understanding as an engineer.

‘My skipper – Sergeant Anderson – knew, he was covering for me. The rest of the crew knew too. They all wanted to come at first, but me alone was best.’

‘But it was a thousand to one she wouldn’t have started. The tank had been there four days.’

‘A thousand to one,’ scoffed Wool. His voice was scornful, as sometimes Pelling’s had been when questioned by those who were mechanically illiterate. ‘I knew Cindy Four like I know my old woman. Better. Better than my old woman.’

He pushed the rest of the Munchy into his mouth. ‘I told that berk Lieutenant Kirkbride that I was the only driver who understood her. But no, he must have his own driver: that little twit Abbott, it was. They had to abandon: gearbox jam. Pausing, that was all you had to understand. Especially coming down from fifth into first. I told him never to use first, she’d start away fine in second even on a mountainside. But he has to use first. They were in a bit of soft-going, a ditch near the water trough. A good driver watches out for that sort of thing and doesn’t get stuck in the first place. Pausing…you know.’

‘Yes, I know.’

‘I could have strangled bloody Kirkbride when I heard. And Abbott. But luckily for them they’d copped it already. Machine-guns got all four of them. Course, I was pleased they’d got themselves out. I’d have never been able to lift four bodies out and get her going.’

‘I think you might have done almost anything that night.’

‘Yeah,’ grinned Wool. ‘I suppose I would have done, but not in eight minutes.’

‘You did all that, just for your vehicle?’ asked Pelling. It was comforting to know that there were other maniacs. Men who would risk their lives to save that of a machine.

‘This wasn’t a vehicle,’ explained Wool, repeating the word with studied distaste. ‘This was a Sherman Firefly. Perhaps you don’t understand what she was. Five 6-cylinder Chevrolet engines on a common crankshaft and a 17-pound gun. Nothing could stop it, nothing.’

‘But the German Mark IVs were still at the end of the track. They could have brewed you up, from that close.’

‘Wilson – our gunner – thought of that. He told me to elevate and traverse the 17-pounder so that the Teds would get an eyeful of it against the skyline.’

‘But you were alone. You couldn’t have loaded, fired and driven the tank, all by yourself…’ But already Pelling wasn’t so sure.

‘No need. If I’d been in those Mark IVs I would have scarpered, too. Tank men understand that. You don’t hang around to get brewed. Our 17-pounder was ace of trumps. They buggered off, didn’t they?’

‘They must have thought it was an ambush,’ said Pelling.

‘They didn’t know what to bloody think. I had them doing their nut. I fired my revolver, all six rounds, at both of them. I knew that they’d hear that O.K., and that’s all the commanders would need to keep their swedes under cover. When you are closed down you can’t see bugger-all. Only tank crews understand how bloody helpless you feel with the lid on. You’re always convinced that there’s some sod of an infantryman farting about under your elbow with a bazooka. That’s all it needs to brew you, whether you’re in a Panther or a pantechnicon.’

‘I never realized that the visibility was so poor,’ said Pelling.

‘Good God, yes. And then there were those bloody ditches. I never saw any of those in the south, but as soon as we reached that bloody ditch country I’d do anything to avoid driving down even a long straight road in daylight unless we had the hatches up and the old Andie shouting left and right. It’s no picnic, I tell you.’

‘But you were hit.’

‘Yeah, funny that. Only time, too. That bugger in the second Mark IV let me have a 75-mm. armour-piercing over his shoulder as he went over the ridge.’

‘We heard it strike the armour.’

Wool chuckled. ‘I’ll bet you did; so did I. Made my head sing for a week and took about a quarter of a hundredweight of metal off the side of the turret. Gouged it out as neat as a chisel mark.’

‘We thought you were a goner.’

‘The whole inside of the tank lit up bright yellow. I could see my controls and the gears and stuff, brighter than I’d ever seen it before! Then it went orange and glowed red hot at the point of impact before it all went dark again. I thought I was going to brew. The old Sherman had a terrible reputation for brewing. Ronsons, they called them; automatic lighters, see?’

‘Didn’t they ask you about the damaged turret when you got the tank back to leaguer?’

‘You say leaguer, do you. My mob always said laager. No. Well, yes, they did, but I kept my mouth shut. I didn’t want any trouble about it. They guessed it was me that brought it back, of course, but nothing was ever said.’

‘They must have thought it was an ambush, Mr Steeple.’

‘But who the devil’s driving it, sir?’

‘It must have been that little Corporal of yours, Steeple. The one who never stops smiling.’

‘He’s not one of my chaps, sir. I thought he was with you.’

‘Deserves a medal, whoever he is. I’d get your chaps together and pull back until first light, Steeple. You can’t defend this place with half a dozen Lee Enfields and a Bren. We can congratulate ourselves upon not going into the bag this night.’

‘Indeed, sir, or worse.’

Pelling’s voice was flat. ‘Or worse. Quite so.’ Was it fatigue that made him daydream so readily?

Thirty years ago it was, when I came closest to meeting my maker. Father Franco nodded, he’d heard the story before, as Father James well knew, but Compline was done and the evening still light. Here in the shadowy corner of the great hall the stories that he told seemed from another world. And yet Father James was not the only cleric who had been a professional soldier, and the things of which he spoke had taken place not many miles away from where the cliff-like monastery caught the harsh sunshine and tolled the hours of ceaseless prayer.

‘I’d have put you in for an M.M., Wool, but I had no idea of who you were.’

Wool was not impressed. ‘It’s all good and nice, you saying that now. I never got a medal, and what good would it do me, anyway? Frankly, I’m more interested in Munchy outlets.’

‘You saved twenty or more lives that night. Drove off an armoured attack, single handed. There’s not many men who can say that.’

Wool was scarcely listening. ‘She was a lovely bus, Cindy Four. Lucky tank, too. All four of us went through fifteen months without a scratch. Bert Floyd – the loader originally – copped it three days after being recrewed. It was only the gear-box that ever gave trouble, and I could handle that. I knew the smell of her: lovely. That night as I strapped tight into the seat and grabbed the sticks I could smell the leather and the oil that the sun had warmed during the day. The Betty Grable pin-up was still next to the visor, and so was the red-painted ammo box from Sicily where Andy kept his bottled beer and a pair of carpet slippers.’ Wool laughed. ‘If we’d ever had to abandon, Andy would have been dancing about a battlefield in slippers. And when she started – beautiful!

‘It broke my heart when they re-equipped us with Comets. I took Cindy back to the depot myself. I got special permission from the C.O. He said they were going for training, but the R.S.M. at the depot said they were to be sold for scrap. If I’d have had the money I’d have bought her. We tried to have a whip round but none of us had enough to even start. A bloody rotten shame,’ said Wool bitterly, ‘those Chevvy five by sixes were every bit as good as the V-8 jobs.’ He plucked Pelling’s sleeve and whispered, ‘I had to do for her myself.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘At the depot,’ said Wool. ‘I poured sand into her and pushed her up to full revs. She stalled, horrible. I’d brought the sand in my small pack. The boys all agreed with me. No one could get on with that gear-box except me, and Wilson’s turret had a lot of funny little ways that no one else would have understood.’

‘I wish I’d seen her,’ said Pelling quietly.

‘To you she would have looked just like any other Sherman.’

‘Oh, no,’ protested Pelling. ‘I understand what…’

‘You, you, you…’ spluttered Wool, ‘you thought she was a Churchill. It was you went there to blow her up!’

‘I didn’t know,’ said Pelling.

‘I couldn’t get you a job,’ said Wool. He sniffed loudly and wiped the back of his hand across his eyes. ‘So don’t build your hopes on me.’

There was no more to say. Wool started the car even before Pelling scrambled out. He accelerated so that the gravel rattled against the pumps and he swung out of the forecourt on to the main road with an agonized squeal of tyres.

Pelling waved, but Wool didn’t look back. He watched the car as it grew smaller upon the long straight road south.