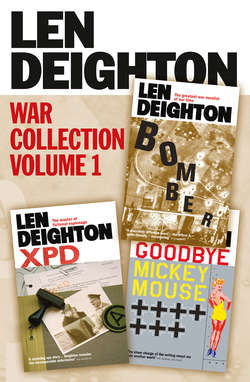

Читать книгу Len Deighton 3-Book War Collection Volume 1: Bomber, XPD, Goodbye Mickey Mouse - Len Deighton - Страница 19

Chapter Ten

ОглавлениеThere were vehicles that every sentry at the Wald Hotel could recognize. For instance, the commanding officer’s Mercedes, the daily mail and ration lorries and the afternoon transport that went to the railway station. For these the ornate hotel gates were folded back well before their arrival. At the approach of an unrecognized vehicle, however, it was customary to challenge it and scrutinize the driver’s papers before the gates were opened. The muddy Kübelwagen did not decrease speed when the two SS sentries walked to the middle of the road. Mausi Scheske held up his hand but finally stood back behind the sentry box. It was to the credit of the other sentry that he did not jump aside until the last moment when the front offside mudguard caught him a glancing blow on the leg. Damage to his knee-cap resulted, some weeks later, in the removal of a cartilage. The motor stopped after striking and bending a spray of wrought-iron oak-leaves. Its mudguard suffered another dent.

‘Officer of the guard!’ bawled the man in the front seat of the car, making no attempt to get out nor sparing a glance for the sentry who had been knocked full-length upon the gravel. Guard dogs barked and six armed and equipped soldiers stumbled to be first out of the gatekeeper’s lodge that was now used as a guardroom. They were clamping their helmets to head and fixing bayonets and all the time were treated to loud complaints from the officer.

‘Open the gates, pick that fool up. Officer of the guard! Why aren’t you saluting? Where’s that man’s pack? Officer of the guard! Move these clowns off the path. You know how long you lot will survive on the East Front? Twenty-four hours. Why is that helmet dirty? Where in the name of bloody blue blazes is the officer of this pitiful shambles of a stumbling band of crippled incompetents? Officer of the guard!’ He screamed as loud as possible and the starlings in the nearby trees rose into the blue sky in alarm. No less alarmed were the Scheske boys, Mausi and Hannes, who for the first time were seeing a Knight’s Cross winner, grimy with the dust of battle, here before their very wide eyes.

‘Yes, sir?’ said a young officer, still breathless. He’d heard the noise while lying on a bed in the guardroom with his boots off.

Fischer yelled his own particulars like a recruit: ‘Sturmbannführer Fischer from Panzergrenadier-Division “Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler” on attachment to SS Division “Hitler Jugend”, Beverlo, Belgium.’ Give these kids and armchair soldiers the whole lot in the teeth, that was the only way to treat them.

‘Yes, sir,’ said the young officer. He took Fischer’s travel papers. He’d heard that a new élite SS division was being formed. ‘That’s the sort of unit I’d like to be assigned to.’ Quietly he added, ‘A man forgets he is a soldier in these backwaters.’

‘So I notice,’ said Fischer. He opened his leather overcoat to replace his papers, which the young officer of the guard had not examined. The Knight’s Cross tinkled against his top button and he saw the young man’s eyes drawn to it. More than anything else the young officer wanted that. A Knight’s Cross holder could do no wrong. Headwaiters provided the best tables and hotels their best rooms, queues vanished, girls submitted and even senior officers showed respect. How, he wondered, had this dirty fellow gained his.

He looked at both of the men in the car. Each of them had a P38 pistol in a leather holster strapped to his waist with a lanyard from its butt. On the VW’s dashboard there was a machine pistol in metal clips. There was an oily rag around its bolt and deep into the clumsy wooden stock of the gun the name Fischer had been carefully carved. So had a line of twenty-eight notches.

Fischer removed his peaked cap and wiped its sweaty leather band with a dirty handkerchief. His skull showed pink through the closely cropped hair. On it were the white worm-like scars of childhood bumps and falls and a long furrow that could only have been made by a bullet. He tucked the handkerchief into his sleeve as the English were reputed to do. The young guard commander noted this fine touch of sophistication.

‘I want petrol and a new set of plugs.’ Fischer rubbed his oil-blackened hands together briefly. ‘We’ve had trouble with the motor.’

‘And food, bathroom and bed?’

‘The motor first.’

‘Immediately, Herr Sturmbannführer,’ said the young officer.

Now the sentries were alert and stiff with anxiety. That’s all they needed, thought Fischer, a real soldier here to light a fire under them. The young officer’s accent was that of a country boy. Racially pure, outstandingly fit and as ideologically sound as a dull-witted yokel could be. It all fitted Waffen SS selection policy but sometimes Fischer wondered if the policy was sound.

‘Your kit to your room?’ said the boy slowly.

‘And put a guard on it. I’m carrying valuables.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And feed my driver and give him a place to sleep. He hasn’t closed his eyes for fifty-six hours.’

The young officer looked at the high-cheeked driver.

‘Are we taking Asiatics into the SS now?’

‘We have a whole division of them in training – 14th SS Freiwilligen-Division Galizien. Two hundred and fifty of them have gone to the Junkerschule. By the time you get to the east they’ll have Ritterkreuze dangling on their collars and you’ll be saluting them.’

‘Ostvolk?’

‘The Reichsführer says they are comrades. You don’t object?’

‘No, sir,’ called the young man loudly. Fischer gave a sour smile.

The gates were wide open. Fischer signalled with his finger that the driver should start up.

The young officer said, ‘Follow the gravel drive. You’ll see the old hotel building. I’ll phone ahead so that they’ll have orderlies to attend to your baggage. And I will phone the kitchen too.’

‘You’re getting the idea, boy,’ said Fischer as the car rolled forward. He turned to his driver and in careful German said, ‘Petrol, sparking plugs, bath, food, sleep. It’s now 15.00; the Kübelwagen ready by 22.00.’ He held up his fingers.

‘Frauen?’ said the driver.

‘No Frauen, you big ape,’ said Fischer. ‘This is Germany. Wait until we are across the border.’

Half understanding, the Ukranian smiled so that his narrow eyes almost closed. He nodded his head.

The inhabitants of Altgarten wore the tired faces that years of war, blackout, rationing, overtime and loneliness bring to the people that endure them. The uniforms were coarse and the civilian suits threadbare. The girls’ dresses were homemade, although here and there in the crowd one saw fine furs or pearls that had made a journey in a soldier’s kitbag.

‘What time do you leave?’ asked Anna-Luisa. She was giving his shoes an extra polish as she always did just before he returned to duty.

‘Three o’clock,’ answered Bach. ‘A staff car will take me.’

‘I’m impressed.’

‘An old friend, on the staff of General Christiansen. He has to go from Dortmund to The Hague several times a month. He often gives me a lift.’

‘You shouldn’t have told me.’

‘I want to tell you everything,’ he said. She packed clean laundry into his case, folding and smoothing it with a newfound dedication.

Sometimes Oberst Max Sepp travelled in General Christiansen’s Mercedes, complete with imperious horn and flying pennant. Today Bach was disappointed to find him in a Citroen. It was a factory-fresh car specially made for the Wehrmacht and newly painted Luftwaffe blue, but it hardly compared with the Mercedes and its throaty roar and silver supercharger pipes. Even Max was less impressive than usual, hunched in a badly creased cape and battered peaked cap. As they stood on the pavement August glanced into the sky. It was a habit he would never lose. Six miles in the sky above him the Met observation Spitfire pilot had seen the whole sweep of the cold front and its attendant hammerhead clouds and black twig-like base. He scribbled upon the notepad attached to his thigh and while his attention was distracted from the controls the aeroplane lost 500 feet of altitude. This brought it low enough for condensation trails to form, although only for a minute. At 420 mph that minute meant a thin white scar seven miles long across Krefeld’s blue sky.

‘One of our fighters,’ said Max. August didn’t reply; he threw his leather overcoat on to the driver’s seat and got in.

Max Sepp was a plump white-haired man in his middle fifties. He was on the staff of the Military Governor of the Netherlands. He was Controller of Civilian Fuel Supplies, about which, as he freely admitted, he knew little or nothing. Before the war he had been a forestry official.

‘This is the life,’ said August, settling into the back of the car with Max as the driver closed the door and saluted. Anna-Luisa waved and August waved back.

The car moved off. ‘The best job in the war,’ said Max. ‘When I go on leave I feel ashamed at the arduous life they lead on the home front.’

The driver had done this same journey a thousand times. From Mönchenstrasse where Bach lived he drove across Dorfstrasse, the big main street, and into Richterend, the short cut round the back of St Antonius Hospital. The old building was dwarfed by the new training centre behind it, while on their left lines of unpainted huts on the waste ground stretched as far as Sackgasse and the slums behind the gas-works.

‘What’s that bloody great place?’ asked Max. ‘A concentration camp?’

August Bach looked at his friend a moment and glanced at the back of the driver’s head before replying. ‘No,’ he said finally, ‘it’s a medical centre for amputees. Men from the East Front and civilians from the bombed cities. They learn how to use false limbs there. They take a walk into Dorfstrasse …’

‘And frighten the kids and look at the empty shops. Lovely.’

‘Is that what a concentration camp looks like, Max?’

‘If either of us knew that, my dear August, we would probably not say.’

‘Probably wouldn’t be sitting here,’ said August.

‘How right you are.’ Max Sepp smiled grimly. He looked out of the window as the car turned the corner at Frau Kersten’s fruit farm and jolted heavily over a badly repaired place in the road.

‘An air raid?’ asked Max.

‘Altgarten’s one and only. Last March. An RAF plane jettisoned incendiary bombs across the potato fields and two high explosive bombs. One on the road, one on Frau Kersten’s outhouse. She has French prisoners of war working on the farm now. She made them fix up the barn and mend the road.’

‘They did a better job on the barn than on the road.’

‘She didn’t give them the road to live in.’

‘Smart woman, Frau Kersten,’ said Max with a laugh. The car turned north-west on to the road that they would follow to Nieukerk and all the way to Arnhem. On the left, Frau Kersten’s potato fields stretched away to the flat horizon. Long lines of bent figures were lifting the waxy yellow potatoes that August liked so much. There were children among them, for the schools had given older boys the traditional holiday to help with the crop. As lines moved forward their forks raised the dry soil so that the breeze carried it in dust clouds across the fields behind them.

‘They are fine potatoes,’ said August.

‘Ah, potatoes! How could the Wehrmacht fight without them. Frau Kersten must be doing very nicely out of the war, August. A smart woman. Now that’s a direction you might be looking.’

‘What do you mean, Max?’ August couldn’t help laughing at the face Max pulled in answer to him.

‘What do you think I mean, you old rogue,’ said Max. ‘You think I believe you spend all your time embracing your binoculars and flirting with those seagulls around that radar station of yours.’

‘Just lately the RAF have been keeping me busy.’

‘Not too busy for that, August.’

‘I’m in love, Max, I’m going to get married.’

‘To the RAD girl?’

‘Yes.’

‘We have a lot of RAD girls working in the Military Government. It never works out.’

‘Whatever do you mean?’ said August.

‘Marriages with the RAD girls clerks. We have a couple of requests every month. I usually post the girl away. Unless she’s pregnant. In that case I post the man.’

‘You’re a cold-hearted swine, Max.’

‘Your girl … is she? …’

‘Damn you, Max, no. At least …’

‘There you are, August. Face the truth, old friend. A moment’s fun, a convenient relationship.’ He paused. ‘For a time. Not for a marriage, August.’

‘I love her, Max.’

‘See how it goes for a month or two.’

‘There’s a war on, Max. And God knows how old I’ll be when it ends! No, this is right for me. And right for her too.’

‘Cigar?’

‘Thank you.’ August sniffed at it appreciatively.

‘The Controller of Civilian Fuel Supplies, Netherlands, is a post that brings a privilege or two.’

‘All right, she’s just a naïve young girl, but I’ve had enough of complex sophisticated people. If she’ll put up with my devious complications, I’ll be happy to have her simple soul.’

Max smiled and lit the cigar for him. For quite a long time they both looked out of the car windows without speaking. It was odd, thought August, one can know a man for many years, and then suddenly half a dozen sentences reveal how little communication there truly is between the two of you. Perhaps all human relationships are like that. Perhaps the best that he could hope for in a marriage to Anna-Luisa was that disenchantment would come slowly, and the bitter aftermath of disenchantment – the black despairing hatred – never even begin. He looked at Max; how indolent and comfortable he was. He leaned back, his eyes closed as they sped along the clear main road.

‘Our roads,’ remarked Max. ‘Could we have imagined such wonderful roads when we were children?’

‘Could we have imagined war on two fronts and the need to move armoured divisions on interior lines?’

‘You’re a miserable fellow today. Admit the Führer’s roads are wonderful.’

‘The roads are wonderful, but are roads the thing we most urgently need? I can’t help thinking that the great Autobahnen were built across the land in order to convince us that Germany is not a conglomeration of disparate and unfriendly principalities.’

‘Well, today I bless the fine roads, for we have a detour: Deelen.’

‘Will it make us late?’

‘You won’t miss your appointment with the Tommis.’

‘How late?’

‘Sixty kilometres to Deelen, Deelen to your radar site can’t be more than one hundred and fifty kilometres, even after dropping me off in The Hague.’

‘How long at Deelen?’

‘Stop being so nervous, August. We’ll have no local traffic in the border zone, a few convoys between Utrecht and The Hague and then nothing at all in the prohibited coastal zone. When we get to Deelen you’ll be fascinated. I’ll have to drag you away, you’ll see.’

The first traffic holdup was on the far side of Geldern. Teenage officer cadets, stripped to the waist and gleaming with sweat, were working like a chain-gang to replace a damaged bridge section in record time.

They were only a couple of kilometres past that when an oncoming convoy halted them again. August watched the twelve-ton half-tracks, and the 8.8 cm flak guns they trailed, creep past. It was a large battery complete with fire-control equipment and personnel in full battle order. Three of the guns were crewed by Flakhelfer. These Hitler Jugend, some only fifteen years old, were dwarfed by the seats of the giant tractor. Their steel helmets came low over their unsmiling faces. They wore brightly coloured badges and shoulder-patches and red and white swastika armbands. At their waists each one had a dagger.

‘Hitler Jugend volunteers,’ said Max.

‘Conscripts,’ said August.

‘Kids?’

‘That’s it.’ How soon would Hansl be accoutred thus and fed into the endless war? Max counted the guns as they rolled past. ‘Twenty-eight guns,’ exclaimed Max. ‘Fantastic.’

‘Grossbatterie; under centralized fire control. At first it was two or three sites combining, now they have up to forty guns under one control.’

‘Is that good?’

‘At least the flak keeps the RAF up high. Without flak the Tommis would come down on the deck and put their bombs into our factory chimneys.’

‘You know, August, my friend, there are quite a few homeless civilians living in the Ruhr who would prefer that.’ He laughed.

A flak officer noticed the dark-blue Citroen with its Luftwaffe number plates and came across to apologize for the delay. He was a stern-faced young man, steel helmet, fair moustache and a non-regulation pair of soft kid gloves that came into view as he saluted.

‘There are road repairs in Geldern,’ said Max Sepp. ‘You won’t get these contraptions through the town.’

‘I know, sir,’ said the officer, ‘but we turn off to Wesel before the roadworks.’

‘The road into the Ruhr from Wesel is even worse,’ said Max. ‘I know this district well.’

‘Our destination is Ahaus,’ said the flak officer.

‘Why Ahaus?’ said Max. ‘If it was left to me I’d pull all the flak back into the Ruhr. There you can be sure of a crack at the terror flyers. You’ll be lucky to see any Tommis at Ahaus.’

‘The policy is still an air defence corridor along the Netherlands border,’ said August.

‘My lads are keen,’ said the officer. ‘They’ll be disappointed unless they see action soon.’

August replied, ‘“No great dependence is to be placed in the eagerness of young soldiers for action. For fighting has something agreeable in the idea to those who are strangers to it.”’

The flak officer was puzzled. He pulled at the fastening of his glove.

‘Vegetius,’ supplied August.

‘A Roman military writer of the fourth century,’ explained Max Sepp.

‘As the Herr Oberst wishes,’ said the officer respectfully. Three huge searchlights trundled past them. He saluted again and swung aboard one of the slow-moving tractors to join his young enthusiasts. The Citroen moved forward.

‘You shocked the fellow,’ said Max.

‘I didn’t mean to,’ said August.

‘Why worry?’ said Max. ‘With that medal at your throat you can afford to be blasé about heroism. But in case you should think me an untutored serf, Vegetius was also the man who said, “Let him who desires peace prepare for war!”’

‘We all say something we don’t mean once in a while,’ said August.

Max laughed, and August wondered if he had not been too quick to judge his old friend.

There was another quarter of a mile of the traffic jam before the cause of it was revealed. There a Bedford Army lorry and an Opel car were locked in embrace. A young NSKK man was directing the traffic on to the grassy verge around the debris while three other NSKK men were extricating the unconscious driver from under the lorry’s bent steering column. The rear part of the Bedford had broken through a hedge and from it boxes of fruit had fallen and split open. Pigs from the orchard were making the most of their good luck.

‘Those bloody British lorries,’ said Max. ‘They shouldn’t allow them on the road.’

‘But after Dunkirk there were so many.’

‘With right-hand steering. Half of these lorry drivers are Motor Corps kids. They are taught to drive in three weeks and then they come on the road and kill anyone who gets in their way.’

The NSKK boy waved them forward and they bumped on to the grass. It was well ploughed up now and the Citroen’s wheels were spinning for a moment before getting a grip. Max leaned out of the car as they passed the traffic man. ‘Those right-hand drives are death traps,’ he said.

‘I don’t speak German,’ said the traffic man. ‘I am French.’ He had the same green-and-black uniform that the Germans had but he wore a tricolour badge on his sleeve and now he tapped it. Max was furious. ‘What bloody use are they?’ he shouted loud enough for the boy to hear.

August said, ‘We’re short of manpower, Max. Russia is drinking our population as fast as we can get them there.’

‘A Frenchman,’ said Max angrily.

‘They are a logical race. They should make good traffic police.’

‘Huh,’ said Max. ‘Logical. They put a knife between your ribs and spend an hour explaining the rational necessity for doing it.’

‘That sounds like a lot of Germans I know.’

‘No, a German puts a knife into your rib and weeps a sea of regretful tears.’

August smiled. ‘And after the Englishman has wielded the knife?’

‘He says, “Knife, what knife?”’

August laughed.

From there on, apart from a traffic jam in Kleve and a long line of traffic crawling through a military police check at the Waal bridge, they moved fast. August dozed off until Max nudged him.

‘We’ll be at Deelen in five minutes or so,’ said Max.

‘Deelen air base or the Divisional Operations Room?’

‘Number One Fighter Division. They control the whole damned air battle there: the whole of the Netherlands, Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, and even parts of Hesse and Belgium. Been there before?’

‘Last year.’

‘Ah yes, the old sanatorium buildings. Wait till you see the new bunker. When I first saw it, August, I realized for the first time that, no matter what the Amis and Tommis do, they can never win against organization like ours. On the control map there is every night fighter, bomber, flak unit, civil-defence unit. It’s like magic.’

‘We need every bit of magic we can get, Max. Last year the RAF kept flying right through the bad winter weather. There was no chance for a breathing-space. We must stop these people within the next few weeks or we can be sure they’ll keep bombing us right through next winter. What’s the good of winning a war if our families, our homes, our cities, museums, and culture are bombed to destruction. We can move our Tiger tank factories deep underground, but we can’t put Speyer Cathedral or Cologne underground.’

‘The experts at OKL say that if we can crack the morale of the bombers this year, they’ll give up bombing the cities.’

‘The only way I know of cracking their morale is shooting them down.’

‘Well, of course. They say if we could bring their casualty averages up by just two and a half per cent, the RAF would have to change their tactics.’

‘Now you understand why I mustn’t be late back,’ said August. ‘A short summer night like tonight, the moon almost full. If they come tonight and we don’t knock down a record number of them we don’t deserve to win.’

The Luftwaffe Citroen stopped at the first of the HQ’s road blocks. The Luftwaffe sentries with their sub-machineguns looked strangely out of place in the candy-striped sentry boxes. An elderly sentry checked their papers and waved the car on. It had rained heavily here and the striped box made dazzling reflections on the shiny road. The bunker itself was in beautiful forestland south of the airfield. The tall beech trees were dripping on to the sunlit paths and beyond the woodland patches of heather were near to flowering.

They got out of the car. There was a smell of resin from the sun-baked pine trees and also the damp dark smell of mould. Deelen airfield was only a stone’s throw beyond the trees and from there August caught the sound of a light aircraft. He waited until it came into view above the trees. It was a white two-seater biplane climbing steadily and earnestly without showmanship.

‘That’s what I call an aeroplane,’ said August. ‘If only flying had stayed like that, instead of giving way to scientists, horse-power, calculating machines and control systems.’

‘You mustn’t complain about that, my good August,’ said Max. ‘You are a controller, remember.’

The white biplane banked and turned neatly. Its fabric was still wet with rain and its wings flashed in the sunlight. The little plane kept climbing in spirals, like the diagrams in training manuals. Then, just as deliberately, it set course on a reciprocal of its take-off path and passed over them again. Before they could turn away the puttering of the white trainer was drowned by the roar of a twin-engine Junkers. The great black machine appeared over the leafy oak trees like some new sort of flying beetle. Its sting-like aerial array seemed to quiver as it searched for the other plane. In a moment it had gone.

‘What a beauty,’ said Max. ‘For the time being, I’ll take the calculating machines and horsepower every time.’

The bunker was truly gigantic. Its entrance road sloped down to a levelled site several metres below ground level. In spite of this the bunker towered above the surrounding woodland. It was as high as an apartment building and as long as a city block. Its roof was three metres of concrete laced with steel rods and heavy steel girders. Every lesson learned in the first years of war had been embodied in its design.

‘It’s indestructible,’ said Max. ‘It will stand there for hundreds of years after the war is over. Even if you wanted to remove it, it would be impossible.’

Max was enjoying August’s surprise. ‘Take no notice of all those windows in the wall,’ said Max. ‘That’s just to give some light to the office workers. Behind that layer of offices, the concrete internal structure is many metres thick.’

The doors were one-centimetre steel, hung on hinges as big as fists. The concrete corridors were noisy with Luftwaffe personnel, many of them young girls. Max Sepp knocked briefly upon an office door and marched into an office crowded with Luftwaffenhelferinnen, uniformed girl communication auxiliaries. Max was on first-name terms with them. He collected a metal document-case and gave it to his driver to carry. Max settled down to gossip with one of the girl auxiliaries. From among the young officers who received Max’s cigars one elected to show August the ‘Opera House’ itself. He was a dark-eyed young man. He put the cigar away in his desk and reached for his cap. He had grown a blunt black moustache to imitate the one Dolfo Galland, the popular young general of fighters, wore. August guessed he’d smoke his cigar in similar mimicry. With a seeming disregard for convention or discipline he kept his left hand thrust deep into his jacket pocket in a rakish manner that well suited the night-fighter clasp on his chest and German Cross on his top pocket.

The young Leutnant took August upstairs. The outer shell of corridors gave on to the inner chamber at three levels. At the top of the staircase they passed through another identity check by an armed sentry. The Leutnant said to August, ‘There is a drill on at present – Pheasant Alert – so we must keep very quiet.’

As they entered the cool dark Battle Room August shook his head in disbelief. The Leutnant smiled; every visitor was amazed. It had become a show place for top Nazi VIPs and this was the place to stand for a first glimpse. As August’s eyes became accustomed to the gloom he saw that it was indeed like an opera house. Seated rank upon rank in front of them were Helferinnen, each one crisp and neat in her white uniform blouse. He saw only the backs of their heads, as would a person standing at the rear of a steep theatre balcony. Far below him, in the orchestra stalls, were rows of high-ranking control officers. Everyone’s attention was upon the stage. For hanging where a theatre’s curtain would hang there was a glass map of Northern Europe. The green glass map was fifteen metres wide and its glow provided enough light for August to see the rows of white faces peering at it and the papers on their desks. On the walls beside the map there were weather charts and a complex board that showed the availability of reserve night fighters. The cool air, silent movement and green light conspired to make the atmosphere curiously like that of an aquarium.

Each of the girls in the balcony with them had a spotlight. From the fresnelled lens of each one was beamed a small white T to represent a constantly moving RAF bomber or a green T to represent the fighter hunting it. As the map-references came over the girls’ headsets they moved the white bombers across Holland and Northern Germany in a neat line. Down in the stalls the phones were in constant use and there was a shuffle of papers and movement. The air-conditioning made a loud humming sound and it was cool enough inside this vast concrete bunker to make August shiver even on this warm summer’s day. From here phone and teleprinter cables stretched across the land to airfields, watchtowers, radar stations, radio monitors and civil-defence headquarters. Even U-boats, and flak ships off the Dutch coast, reported aircraft movements to this bunker which the Luftwaffe had christened the Battle Opera House.

Overlapping circles of light had appeared on the map. Each one was a radar station like August’s own. Each one had two night fighters circling above it waiting to pounce upon a bomber coming into range of its magic eye. Now and again one of the T lights was switched off as a bomber was destroyed.

The young Leutnant had noticed August’s Pour le Mérite and decided that he was worth a fuller explanation than most of the rubberneck visitors that he showed around. He pointed to the six rows of stalls far below them.

‘It’s in the two front rows that the battle decisions are made. The Major-General third from the left is the Divisional Controller. On each side of him he keeps an Ia – Operations Officer. On the far left is the NAFU or Chief Signals Officer. Second to the right of the Div Controller, the officer with the yellow tabs is the Ic or Intelligence Officer. The old man on his right is the senior Meteorology man. The second row of officers, the ones speaking into phones all the time, are Fighter Controllers carrying out the orders. On that same desk there’s a Flak Officer, Radar Controller and Civil Defence Liaison.’

‘Who is the man in the tinted-glass office on the left?’ asked August.

‘Radio Intelligence Liaison Officer. He only comes out to talk with the Divisional Controller. Even then it’s in a whisper.’ He smiled, he had the cynical attitude to boffins that operational pilots always have.

The T-shaped lights moved slowly in a straight line towards Berlin.

‘What do you think?’ asked the Leutnant.

‘It’s damned impressive,’ said August.

‘It’s not always as calm as this, I’m afraid. On a real raid things get more hectic. I’ve seen them shouting at each other down there.’

‘And those little white lights don’t disappear so quickly,’ said August.

‘Ah,’ said the Leutnant. ‘That’s the real difference, I’m afraid.’ He spoke like a man who knew how big the sky was on a dark night.

They watched the ‘air raid’ proceed for a few more minutes. Still the white T lights that represented the bombers kept on their narrow line. The controllers practised dealing with the ‘stream tactics’ that the RAF had developed as a way of overwhelming the radar defences of just one zone instead of presenting single targets piecemeal to several radar sets and accompanying night fighters.

‘What about the Mosquito they send in to mark the target? If our planes could get up high enough to knock that down, the stream wouldn’t know where to drop their bombs.’

‘Exactly,’ said the Leutnant. He swung lightly round on his toes with his arm stiffly akimbo, giving him a curious effeminate stance. He eyed Bach speculatively and then decided to confide a secret.

‘Tonight we have a surprise awaiting them.’

‘The Ju88s supercharged with nitrous oxide?’

‘“Ha-ha” they call them – laughing gas, you see – you’ve heard about them, eh?’

‘What idiot thought of that code name?’

‘And 12.8 guns on railway mountings, we are going to try everything we know tonight. I don’t know, some fool in Air Ministry, I suppose.’

‘If they cooperate by flying over the railway guns,’ said August doubtfully.

‘They always come in from north to south, and always towards the Ruhr because – we think – that’s the limit of the electronic range. So we can make a guess at it. We’ll be more or less in position.’

‘Radio intercept predict a big one tonight,’ said August. He looked at his own radar station on the glass map, its range indicated by a dull lit circle. It was exactly placed between the RAF bomber airfields of East Anglia and the Ruhr. ‘I’m at Ermine,’ said August.

‘I know, sir,’ said the Leutnant. ‘I don’t think you’ll have much sleep before morning.’ Now August could see that the young Leutnant’s stiff left arm was artificial.