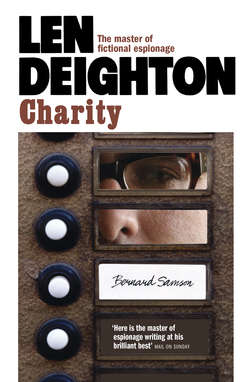

Читать книгу Charity - Len Deighton - Страница 8

2

ОглавлениеThe SIS residence, Berlin

‘That bloody man Kohl,’ said Frank Harrington, speaking with uncustomary bitterness about the German Federal Republic’s Chancellor. ‘It’s all his doing. Inviting that bastard Honecker to visit the Republic has completely demoralized all decent Germans – on both sides of the Wall.’

I nodded. Frank was probably right, and even if he hadn’t been right I would have nodded just as sagely; Frank was my boss. And everywhere I went in Berlin I found despondency about any chance of reforming the East German State, or replacing the stubbornly unyielding apparatchiki who ran it. Just a few months before – in September 1987 – Erich Honecker, Chairman of East Germany’s Council of State, Chairman of its National Defence Council and omnipotent General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party, had been invited on a State visit to West Germany. Few Germans – East or West – had believed that such a shameless tyrant could ever be granted such recognition.

‘Kohl’s a snake in the grass,’ said Frank. ‘He knows what everyone here thinks about that monster Honecker but he’ll do anything to get re-elected.’

Kohl had certainly played his cards with skill. Inviting Honecker to visit the West had been a political bombshell that Kohl’s rivals found difficult to handle. The Saarland premier – Oskar Lafontaine – had been misguided enough to pose with the despised Honecker for a newspaper photo. The resulting outcry dealt Lafontaine’s Social Democrats a political setback. This, plus some clever equivocations, patriotic declarations and vague promises, revived the seemingly dead Chancellor Kohl and reaffirmed him in power.

Those who still hoped that Honecker’s visit to the West would be marked by some reduction of tyranny at home asked him to issue orders to stop his border guards shooting dead anyone who tried to escape from his bleak domain. ‘Fireside dreams are far from our minds,’ he said. ‘We take the existence of two sovereign states on German soil for granted.’

‘Kohl and his cronies have taken them all for a ride,’ I said. The ‘Wessies’ viewed Kohl’s political manipulation of the Honecker visit with that mixture of bitter contempt and ardent fidelity that Germans have always given to their leaders. On the other side of the Wall the ‘Ossies’, confined in the joyless DDR, were frustrated and angry. Grouped around TV sets, they had watched Kohl, and other West German politicians, being unctuous and accommodating to their ruthless dictator, and blithely proclaiming that partition was a permanent aspect of Germany’s future.

‘It aged Strauss ten years, that visit,’ said Frank. I could never tell when he was joking; Frank was not noted for his humour but his jokes were apt to be cruel and dark ones. From his powerbase in Munich, Franz Josef Strauss had proclaimed something he’d said many times before: ‘The German Reich of 1945 has legally never been abolished; the German question remains open.’ It was not what Honecker wanted to hear. He might have won Kohl over, but Strauss remained Honecker’s most effective long-term critic.

We were downstairs in Frank’s house in Grunewald, the home that came with the post of Head of Station in Berlin. It was late afternoon, and the dull cloudy sky did little to make the large drawing-room less sombre. Yellow patches of light from electric table-lamps fell upon a ferocious carpet of bright red and green flowers. A Bechstein grand piano glinted in one corner. Upon its polished top, rank upon rank of family photos paraded in expensive frames. Playing centre-forward for this team stood a silver-framed photo of Frank’s son, a one-time airline pilot who had found a second career as a publisher of technical aviation books. Behind the serried relatives there was a cut-glass vase of long-stem roses imported from some foreign climate to help forget that Berlin’s gardens were buried deep under dirt-encrusted snow. All around the room there were Victorian paintings of a sooty and hazy London: Primrose Hill, the Crystal Palace and Westminster Abbey all in heavy gilt frames and disappearing behind cracked and darkening coach varnish. Arranged around a polished mahogany coffee table there were two big uncomfortable sofas in blue damask, and three wing armchairs with matching upholstery. One of these Frank kept positioned exactly facing the massive speakers of his elaborate hi-fi system, its working parts concealed inside a birchwood Biedermeier tallboy that had been disembowelled to accommodate it. Sometimes Frank felt bound to explain that the tallboy had been badly damaged before suffering this terminal surgery.

Frank was relaxed in his lumpy chair. Thin elegant legs crossed, a drink at his elbow and a chewed old Dunhill pipe in his mouth. From time to time he disappeared from view behind a sombre haze, not unlike the coach varnish that obscured the views of London, except for its pungent smell. After a period of denial, which had caused him – and indeed everyone who worked with him – mental and physical stress, he’d now surrendered to his nicotine addiction with vigour and delight.

‘I read the report,’ said Frank, removing the pipe from his mouth and prodding into its bowl with the blade of a Swiss army penknife. Seen like this, in his natural habitat, Frank Harrington was the model Englishman. Educated but not intellectual, a drinker who was never drunk, his hair greying and his bony face lined without him looking aged, his impeccably tailored pinstripe suit not new, and everything worn with a hint of neglect: the appearance and manner which knowing foreigners so often admire and rash ones imitate.

I sipped my whisky and waited. I had been summoned to this meeting in Frank’s home by means of a handwritten memo left on my desk by Frank in person. Only he would have fastened it to my morning Berliner doughnut by means of a push-pin. Such formal orders were infrequent, and I knew I’d not been brought here to hear Frank’s views on the more Byzantine stratagems of Germany’s political adventurers. I wondered what was really in his mind. So far there had been little official reaction to my delayed return to Berlin, and the detention in Poland that caused it. When I arrived I reported to Frank and told him I’d been arrested and released without charges. He was on the phone when I went into his office. He capped the phone, mumbled something about my preparing a report for London, and waved me absent. I resumed my duties as his deputy, as if I’d not been away. The written report I had submitted was brief and formal, with an underlying inference that it was a matter of mistaken identity.

I was sitting on one of the sofas in an attempt to keep my distance from the polluting product of Frank’s combustion. Before me there was a silver tray with a crystal ice bucket, tongs, and a cut-glass tumbler into which a double measure of Laphroaig whisky had been precisely measured by Tarrant. He’d put the whisky bottle away again, but left on the table a bottle of Apollinaris water from which I was helping myself. Shell-shaped silver dishes contained calculated amounts of salted nuts and potato chips and there was a large silver box that I knew contained a selection of cigarettes. Tarrant, Frank’s butler, had arranged a similar array on Frank’s side of the coffee table. Apart from Frank’s expensive hi-fi, Tarrant had ensured that the household and its routines were not modified by advances in science or fashion. As far as I could see, Frank did the same thing for the Department.

On an inlaid tripod table, booklets and files were arranged in fans, like periodicals in a dentist’s waiting-room. From the table Frank took the West German passport I’d been using when detained in Poland. He flipped its pages distastefully and looked from the identity photo to me and then at the photo again. ‘This photograph,’ he said finally. ‘Is it really you?’

‘It was all done in a bit of a hurry,’ I explained.

‘Going across there with a smudgy picture of someone else in your passport is a damned stupid way of doing things. Why not an authentic picture?’

‘An identity picture is like ethnic food,’ I said. ‘The less authentic it is the better.’

‘Can you elaborate on that a little?’ said Frank, playing the innocent.

‘Because the UB photocopy, and file away, every passport that goes through their hands,’ I said.

‘Ahhh,’ said Frank, sounding unconvinced. He slid the passport across the table to me. It was a sign that he wasn’t going to take the matter any further. I picked it up and put it in my pocket.

‘Don’t use it again,’ said Frank. ‘Put it away with your Beatles records and that Nehru jacket.’

‘I won’t use it again, Frank,’ I said. I’d never worn a Nehru jacket or anything styled remotely like one, but I would always remain the teenager he’d once known. There was no way of escaping that.

‘You are senior staff now. The time for all those shenanigans is over.’ He picked up my report and shook it as if something might fall from the pages. ‘London will read this. There is no way I can sit on it for ever.’

I nodded.

‘And you know what they will say?’

I waited for him to say that London would suspect that I’d gone to Moscow only in order to see Gloria. But he said: ‘You were browbeating Jim Prettyman. That’s what they will say. What did you get out of him? You may as well tell me, so that I can cover my arse.’

‘Jim Prettyman?’

‘Don’t do that, Bernard,’ said Frank with just a touch of aggravation.

If it was a chess move, it was an accomplished one. To avoid the accusation that I was grilling Prettyman I would have to say that I was there to see Gloria. ‘Prettyman was more or less unconscious. There was little chance of my doing anything beyond tucking him into bed and changing his bedpans, and there was a nurse to do that. What would I be grilling Prettyman about, anyway?’

‘Come along, Bernard. Have you forgotten all those times you told me that Prettyman was the man behind those who wanted your sister-in-law killed?’

‘I said that? When did I say it?’

‘Not in as many words,’ said Frank, retreating a fraction. ‘But that was the gist of it. You thought London had plotted the death of Fiona’s sister so that her body could be left over there. Planted so that our KGB friends would be reassured that Fiona was dead, and not telling us all their secrets.’

Fortified by the way Frank had put my suspicions of London in the past tense, I put down my drink and stared at him impassively. I suppose I must have done a good job on the facial expression, for Frank shifted uncomfortably and said: ‘You’re not going to deny it now, are you, Bernard?’

‘I certainly am,’ I said, without adding any further explanation.

‘If you are leading me up the garden path, I’ll have your guts for garters.’ Frank’s vocabulary was liberally provided with schoolboy expressions of the nineteen thirties.

‘I’m trying to put all that behind me,’ I said. ‘It was getting me down.’

‘That’s good,’ said Frank who, along with the Director-General and his Deputy, Bret Rensselaer, had frequently advised me to put it all behind me. ‘Some field agents are able to do their job and combine it with a more or less normal family life. It’s not easy, but some do it.’

I nodded and wondered what was coming. I could see Frank was in one of his philosophical moods and they usually ended up with a softly delivered critical summary that helped me sort it all out.

‘You are one of the best field agents we ever had working out of this office,’ said Frank, sugaring the pill. ‘But perhaps that’s because you live the job night and day, three hundred and sixty-five days a year.’

‘Do I, Frank? It’s nice of you to say that.’

He could hear the irony in my voice but he ignored it. ‘You never tell anyone the whole truth, Bernard. No one. Every thought is locked up in that brain of yours and marked secret. I’m locked out; your colleagues are locked out. I suppose it’s the same with your wife and children; I suppose you tell them only what they should know.’

‘Sometimes not even that,’ I said.

‘I saw Fiona the day before yesterday. She annihilated some poor befuddled Ministry fogey, she made the chairman apologize for inaccurate minutes of the previous meeting and, using the ensuing awkward silence, carried the vote for some training project they were trying to kill. She’s dynamite, that wife of yours. They are all frightened of her; the FO people I mean.’

‘Yes, I know.’

‘It takes quite a lot to scare them. And she thrives on it. These days she’s looking like some glamorous young model. Really wonderful!’

‘Yes,’ I said. I would always have to defer to Frank in the matter of glamorous young models.

‘She said the children were doing very well at school. She showed me photos of them. They are very attractive children, Bernard. You must be very proud of your family.’

‘Yes, I am,’ I said.

‘And she loves you,’ he added as an afterthought. ‘So why keep stirring up trouble for yourself?’ Frank gave one of those winning smiles that half the women in Berlin had fallen prey to. ‘You see, Bernard, I suspect you planned the whole thing – your train ride from Moscow with Prettyman. I think you made sure that there would be no one else available from here to do it.’

‘How would I have made sure?’

‘Have you forgotten the assignments you arranged in the days before you went away?’ As he said this he toyed with his pipe and kept his voice distant and detached.

‘I didn’t arrange their assignments. I don’t know those people. I did as Operations suggested.’

‘You signed.’ Now he looked up and was staring at me quizzically.

‘Yes, I signed,’ I agreed wearily. His mind was made up, at least for the time being. My best course was to let him think about it all. He would see reason eventually; he always did. No reasonable person could believe that I’d carefully plotted and planned a way to get Prettyman alone in order to grill him about Tessa’s death. But if Frank suspected it, you could bet that London believed it implicitly; for that’s where all this crap had undoubtedly originated. And, in this context, ‘London’ meant Fiona and Dicky. Or at least it included them.

‘Did you try one of those fried potato things?’ he said, pointing to one of the silver dishes. ‘They are flavoured with onion.’

‘Curry,’ I said. ‘They are curry-flavoured. Too hot for me.’

‘Are they? I don’t know what’s happening to Tarrant lately. He knows how I hate curry. I wonder how they put all these different flavours into them. In my day things just tasted of what they were,’ he said regretfully.

I got to my feet. When the conversation took this culinary turn I guessed Frank had said everything of importance to him. He rested his pipe in a heavy glass ashtray and pushed it aside with a sigh. It made me wonder if he smoked to provide some sort of activity when we had these get-togethers. For the first time it occurred to me that Frank might have dreaded these exchanges as much as I did; or even more.

‘You were late again this morning,’ he said with a smile.

‘Yes, but I brought a note from Mummy.’

Surely he must have known that I was going to the Clinic every morning; they’d found two hairline cracks in my ribs, and were dosing me with brightly coloured pain-killing pills, and taking dozens of X-rays. I shouldn’t be drinking alcohol really, but I couldn’t face a lecture from Frank without a drink in my hand.

‘Stop by for a drink tonight,’ he said. ‘About nine. I’m having some people in … Unless you have something arranged already.’

‘I said I’d see Werner.’

‘We’ll make it another night,’ said Frank.

‘Yes,’ I said. I wondered if he’d taste one of the ‘potato things’ and find they were onion after all. I don’t know what made me tell him they tasted of curry, except in some vague hope that the hateful Tarrant would be blamed. Perhaps I shouldn’t have mixed alcohol and pain-killers.

By the time my official confirmation as Frank’s deputy came through I was settled into my comfortable office and making good use of my assistant and my secretary, as well as a personally assigned Rover saloon car and driver. I’d often remarked that Frank had kept the Berlin establishment absurdly high, but now I was reaping some of the rewards of his artful manipulations.

Frank, having resisted appointing a deputy for well over two years, made the most of my presence. He attended conferences, symposiums, lectures and meetings of a kind that in the old days he’d always avoided. He even went to one of those awful gatherings in Washington DC to watch his American colleagues in CIA Operations trying to look cheerful despite the seemingly unending intelligence leaks coming from the top of the CIA tree.

Although in theory Frank’s frequent absences made me the de facto chief in Berlin, I knew that his super-efficient secretary Lydia never missed a day without reporting to him at length, even when this meant phoning him in the middle of the night. So I never emerged from Frank’s shadow, which was perhaps something of an advantage.

My new-found authority granted me the chance to put my old friend Werner Volkmann on a regular contract. Werner was always saying he needed money, although the fees we paid him wouldn’t go very far to meeting Werner’s lifestyle. His business – arranging advance bank payments for East German exports – was drying up. Things were becoming more and more difficult for him because the bankers were frightened that the DDR might be about to default on its debts to the West. But being on Departmental contract seemed to do something for his self-esteem. Werner loved what I once heard him call the ‘mystique of espionage’. Whatever that was, he felt himself a part of it and I was happy for him.

‘Having you here in Berlin, on permanent assignment, is like old times,’ Werner said. ‘Whose idea was it?’

‘Dicky sent me here to spy on Frank.’ I said it just to crank him up. We were sitting in Babylon, a dingy subterranean ‘club’. It was owned by an amusing and enigmatic villain named Rudi Kleindorf, who claimed to come from a family of Prussian aristocrats, and was jokingly referred to as der grosse Kleine. We were sitting at a hideous little gilt table, under a tasselled light fitting. We had been invited for a drink and a chance to see how everything was coming along. Our inspection had been quickly completed and now we were having that drink.

The club wasn’t functioning yet; it was still in the process of being redecorated. The workmen had departed but there were ladders and pots of paint on the stage, and on the bar top too. There had been stories that it was to be renamed ‘Alphonse’, but the Potsdamerstrasse was not the right location for a club named Alphonse. Whatever name it was given, and whatever the colour of the paint, and the quality of the new curtains for the stage, and even some new, slimmer and younger girls, it would never be a place that tourists, or Berlin’s Hautevolee, would want to frequent, except on a drunken excursion to see how the lower half lives. I wondered if Werner had been enticed to put some money into Rudi Kleindorf’s enterprise. It was the sort of thing Werner did; he could be romantically nostalgic about dumps we’d frequented when we were young.

Werner reached for the bottle on the table between us and poured another drink for me. He smiled in that strange way that he did when figuring the hidden motives and devious ways of men and women. His head slightly tilted back, his eyes were almost closed and his lips pressed together. It was easy to see why he was sometimes mistaken for one of the Turkish Gastarbeiter who formed a large percentage of the city’s population. It was not only Werner’s swarthy complexion, coarse black hair, large square-ended black moustache and the muscular build of a wrestler. He had a certain oriental demeanour. Byzantine described him exactly; except that they were Greeks.

‘And Frank?’ said Werner. There was nothing more he need say. Dicky was youthful, curly-haired, energetic, ambitious and devious; while Frank was bloodless, tired and lazy. But in any sort of struggle between them, the smart money was on Frank. Frank had spent a great deal of his long career being splashed in the blood and snot of Berlin, while Dicky was concentrating upon crocodile-covered Filofax notebooks and Mont Blanc fountain-pens. Werner and I both knew a side of Frank that Dicky had never seen. Never mind all that avuncular charm, we’d seen the cold-blooded way in which Frank could make life-and-death decisions that would have consigned ‘don’t-know Dicky’ to a psychiatrist’s couch in a darkened room.

‘What’s Dicky frightened of?’

‘Nothing,’ I said. ‘I can truthfully say he’s frightened of nothing except perhaps an audit of his expense accounts.’ There were voices from behind the tiny stage and then a man came out and played a few bars on the piano. I recognized it as an old Gus Kahn tune: ‘Dream a little dream of me’.

‘So it was Frank’s idea?’ Werner asked. Werner was an impressive piano player; I could see he was listening to the music with a critical ear.

‘It wasn’t anyone’s idea. Not the way you mean. The job was vacant; I came.’

Werner said: ‘Frank has managed without a deputy for ages. Don’t you need to be in London … somewhere near Fiona and the kids? How are they doing?’

‘They are still with Fiona’s parents. Private school with extra tutoring as needed, a pony for Sally and a mountain bicycle for Billy, evenings with Grandpa and plenty of fresh fruit and vegetables.’

‘What are you going to do?’

‘Do? I can’t snatch them away from the bastard without providing something better, can I?’ I said, curbing my anger and frustration. The piano player suddenly ended his experimental tunes, stood up and shouted that the piano was no good at all. A disembodied voice shouted that there was no money to get another. The piano player shrugged, looked at us, shrugged again and then sat down and tried Gershwin.

‘Couldn’t they live in London with Fiona?’ said Werner.

‘It’s an apartment – not fifteen acres of rolling countryside … and Fiona works every hour God Almighty sends. How would we arrange things? I’d have them here if I could think of some feasible way of doing it.’ I looked down at my hands; I had clasped one fist so tight that a fingernail had cut my palm, and drawn blood.

Werner watched me and tried to cheer me up: ‘Well, you don’t have to be in Berlin for ever and I’m sure there’s plenty to do here.’

‘Enough. A Deputy Head of Station is on the establishment. I suppose Frank was afraid that if the position remained unfilled too long it would be abolished. Anyway it gives Frank a chance to disappear whenever he likes.’

‘But it ties you down.’

‘The theory is: I get one long weekend in London a month.’

‘You’ll have to fight for it,’ said Werner.

‘That’s why I’m going this weekend,’ I said.

Perhaps he was right to be sceptical. I could see that events were unlikely to make it possible for me to go across to London so regularly. With Frank’s frequent wanderings, I would be snatching a day or two as and when opportunities came along. ‘This weekend I go,’ I promised him again, and in doing so promised myself too. ‘I’m booked on the plane; I’m seeing the children. And if World War Three starts at Checkpoint Charlie, Frank will have to handle the opening moves all by himself.’

‘You don’t think London might have put you on the shelf? Put you here so you don’t get access to mainstream material?’

‘I handle everything going through here. You need top clearance for that.’

‘Except the secrets that Frank handles and keeps close to his chest.’

‘Not Frank,’ I said, but of course Werner was right. I’d not seen any of the signals about Prettyman, and the questions about moving him, and the complications that arose from his US passport, until I got to Moscow. Who knows if there were other signals expressing interest in my past friendship with Prettyman, or my sometimes indiscreetly voiced suspicions of his role in Tessa’s death.

‘Frank invited me for happy-hour and then read the Riot Act to me. It must have been prompted by London.’

Werner gave me a told-you-so stare.

‘Is London sniffing at me? Why me? Why now?’

‘Because you keep on about Tessa, that’s why. London have sidelined you.’

‘No,’ I said.

‘And this is just the beginning. They’ll get rid of you completely. Firing you in Berlin makes sure you can’t kick up the sort of fuss you’d be able to do if you were made redundant while working in London Central.’

‘Well I’m not going to just forget about Tessa.’

‘You said you had forgotten about it.’

‘When?’

‘You just told me.’

‘Don’t shout Werner, I’m not deaf.’

Slowly and with exaggerated pedantry Werner said: ‘You told Frank you were trying to put the Tessa death behind you. You said the whole business was getting you down. You told me that, Bernie, not half an hour ago.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘But I didn’t mean I was going to forget about it.’

‘What did you mean, Bernie?’

‘I mean I will put aside all my previous suspicions and ideas. I will start afresh. I’m going to look into Tessa’s death as if I’d come to it for the first time. I’m convinced that Bret Rensselaer is behind it all.’

‘Now it’s Bret. Why Bret? Bret was in California, wasn’t he?’

‘If I could get Bret in the right mood, I could get him to spill the beans. He’s not like the others.’

‘But what would Bret know?’

‘Bret had access to a big slice of the Department’s dough. It looked as if he’d embezzled it and some idiot tried to arrest him, remember?’

‘And you saved him. You saved Bret that time. I hope he remembers that episode when he came running to you in Berlin.’

‘He’s not likely to forget it. That shooting at the station changed Bret. They thought he would die. His hair went white and he was never the same again.’

‘But Bret didn’t steal any Departmental money?’

‘Bret was up front in a secret Departmental scheme to siphon money away. By koshering a few millions aside they covertly financed Fiona’s operations in the East.’

‘You told me.’

‘But Prettyman was on that committee too. He put some money into his own pocket. They sent me to Washington DC to bring Prettyman back but he wasn’t having any.’

‘That can’t be true, Bernie. Prettyman is a blue-eyed boy nowadays.’

‘He did a deal with them. I’d like to know what the deal was; but they bury these things deep. That’s why I would like to get Bret talking. Bret was on the committee with Prettyman. Bret was the one who planned Fiona’s defection. Bret would know everything that happened.’

‘My God, Bernie. You never give up, do you?’

‘Not without trying,’ I said.

‘Give up this one now. The people in London are not going to sit still while you light a fire under them.’

‘If no one there is guilty they have nothing to worry about.’

‘You sound very smug. If no one there is guilty, they will be even more furious, more angry, more vindictive to find that an employee is trying to hang a murder charge on them.’

‘If you are right, Werner. If you are right that they have sent me here as the first step in a plan to get rid of me, I have nothing to lose, do I?’

‘If you’d drop it, they might drop it too.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘And everything in the garden would be lovely. But I’m going to find out who gave the orders to kill Tessa, and I’m going to find the one who gave the order to pull the trigger that night. I’ll face them with proof: depositions and any other kind of evidence I unearth. And well before they pull the carpet from under me, I’m going to have them dancing to the tune I play on my penny whistle.’

‘You are just angry. You are just angry that Dicky got the job you should have had. You are just inventing the cause for a vendetta.’

‘Am I? Well let me tell you this, Werner. There was a Canadian nurse on that train with Prettyman. She might have been holding hands with him. She has spent many happy evenings in Washington; or so she told me.’

‘Prettyman was always like that.’

‘She was wearing a brooch that belonged to Tessa.’

‘She was what?’ He gulped on his drink.

‘Oh, I’m glad you still retain the capacity to be surprised, Werner. I was beginning to think there was nothing you wouldn’t nod through. Yes, one of Tessa’s favourite brooches: a big sapphire set in yellow gold and silver and studded with matched diamonds.’

‘How can you be sure that it’s not just a brooch that looks like the one Tessa had?’

‘It’s antique; not a modern reproduction. The chances of finding another one exactly like that are pretty slim. It was Tessa’s brooch, Werner. And the nurse told me it was a gift from Mr James Prettyman. Oh, yes, and from Mrs Prettyman too. But nursie seemed to think it was just junk jewellery. Is that what they all thought?’

‘Did you ask Prettyman about it?’

‘Unfortunately no. I was lifted off the train before I got a chance to beat an answer out of him.’

‘Shall I chase it? Where is the nurse now?’

‘I’ve no idea; home with her family in good old Winnipeg, I suppose. Let her be, Werner. She knows nothing. It might pay off better if I surprise Prettyman with the questions.’

Werner looked unhappy. ‘Please, Bernie. You are going over the top. I know it’s all going to end in disaster. What will you do if they fire you? I’ll do anything you want, but please drop this one.’

‘You and Frank treat me like I’ve just got back from a drunken party to report a flying saucer. I’m not going to drop it until I’m satisfied.’ I gulped the rest of my drink, then got to my feet and looked around the room again. Werner was determined to play baby-sitter for me, and I wasn’t in the mood to be babied. I got enough of that from Frank all week.

‘Then don’t talk to me about it,’ said Werner. That’s all I ask.’

He didn’t say it quickly and angrily; he said it slowly and sadly. I didn’t give any attention to that fact at the time. Perhaps I should have done.

‘This smell of paint is terrible,’ I said. ‘When is this bloody idiot supposed to be opening this dump?’ I noticed with sadness that the old mural had disappeared under a couple of litres of white paint. It had been an imaginative array of hanging gardens, the great ziggurat and naked women dancing through palm trees, done by a drunken artist who had never travelled beyond the Botanical Gardens in Steglitz. I wondered what would replace it.

‘Next Tuesday the builders said, but now they are wavering. The carpenters haven’t finished and the painters have hardly started. They will have to finish and clear up completely before anyone can start polishing the floor. It will all take quite a time. Rudi is looking for somewhere else to hold his opening party. Somewhere bigger. Maybe a hotel.’

‘I can’t just walk away and forget about Tessa,’ I said. ‘I just can’t.’

Werner was closely studying some tiny spots of paint that had been splashed on the table-lamp.

By the time I left, the pianist was playing a Bach partita in a minor key. It wouldn’t be easy to dance to.