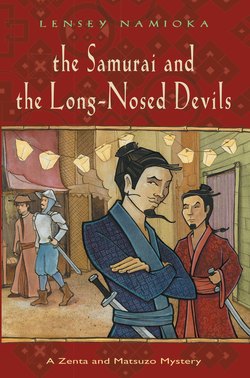

Читать книгу Samurai and the Long-nosed Devils - Lensey Namioka - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Breathless after crossing the mountain pass, the two travelers stood for a moment and looked down on the dark gray roofs of Miyako. The capital city was situated in a small plain surrounded on three sides by mountains. On this July afternoon, the heat lay trapped in the city as if in a large bowl. The air vibrated with the heat, and to the tired eyes of the travelers, the roof tiles seemed to be jumping up and down.

The men each wore two swords thrust into their sashes, marking them as samurai. Their kimonos were of silk and had once been even elegant, but they were now torn and white with dust. On their feet the travelers wore straw sandals nearly falling apart from hard use. Still, the two men carried themselves with the unconscious haughtiness of the warrior class, although it was clear from their shabby condition that they were ronin, or unemployed samurai.

As they made their way down into the city, Matsuzo, the younger of the two ronin, removed his large basket-shaped hat and wiped his face with his sleeve. “How much money do we have left?” he asked.

Zenta, his companion, groped inside the front of his kimono and brought out a few coins. “I’m afraid this is all we have.” Matsuzo’s face fell. “Well, it should be enough for a bath, at least. Let’s go find a public bathhouse.”

Although he was young and had a pleasant, open countenance, it was not his habit to spend much thought on his appearance. But now that he was entering the capital city of Miyako, he was conscious of his grubbiness.

Zenta, several years older and widely traveled, had very different ideas about how to spend the last of their money. “We need food more than a bath,” he said. “We came to Miyako in order to enter Nobunaga’s service. Since he is fast becoming the most powerful man in the country, thousands of ronin are rushing to enlist with him. To improve our chances of being hired, we must make a good first impression by building up our strength with a solid meal.”

Prickly heat was making Matsuzo irritable, and he spoke to Zenta without his usual respect. “How do you expect us to make a good first impression on Nobunaga when we look like this! We won’t even get past the guards at his front gate!”

“Nobunaga is certainly not going to hire two weaklings who are tottering from hunger,” said Zenta. It was true that he looked famished. He removed his straw hat to reveal a thin face with somewhat aquiline features. He was taller than his companion, and he had a naturally spare build which the recent lean days had reduced to near gauntness.

“When we had the fight with those bandits last week, we hadn’t eaten for two days,” retorted Matsuzo. “I don’t remember seeing you totter then.”

But Zenta was not listening. He was drawn irresistibly to a street stall which sold broiled eel. The cook brushed a thick brown sauce on the pieces of eel sizzling on the hot grill, and a delicious aroma filled the air. The hollowness in Matsuzo’s stomach became suddenly urgent and his mouth began to water. Bath forgotten, he found himself following Zenta to the stall.

Before the two men could give their orders to the cook, they heard sounds of quarreling down the street. It was a narrow street, made yet more crowded by the temporary stalls constructed for the coming Gion Festival. Jostling was all too easy, and when the person jostled turned out to be a touchy samurai, the result could be violent.

In this particular quarrel, however, they could hear the shrill voice of a woman. In the next moment she cried, “Let me go! Let me go!” “You are coming with us!” ordered a man’s voice roughly.

Matsuzo turned and pushed his way towards the conflict. He was new to the life of a wandering ronin, and he still cherished the romantic ideal of the samurai as the defender of the weak.

Zenta gave a last regretful look at the broiled eel. After some years as a ronin, he was experienced enough to know that it was best not to interfere in domestic quarrels, which this one probably was. “Whatever you do, don’t draw your sword,” he warned as he reluctantly followed Matsuzo.

Reaching the scene of the conflict first, Matsuzo saw that one of the combatants was a tall, muscular man with a white cotton scarf on his head. The scarf was worn low across the forehead, with the corners tied at the back of the neck. It was the headdress of a warrior monk. For more than seven hundred years these monks, who lived on Mt. Hiei just northeast of Miyako, had terrified the people of the capital, including even the emperors.

Matsuzo was outraged to see that the monk had his grasp on a wildly struggling young girl. She was clearly not a peasant girl, for her skin was fine and white and her kimono expensive looking. Although small and slender, she stubbornly continued the unequal struggle against her huge opponent.

With a sharp twist the girl succeeded in tearing herself free. She looked around for help, and her eyes fell on Matsuzo, standing straight and noble, the very picture of a brave protector. She ran around to his back and put her arms tightly about his waist.

The monk turned and saw the young ronin. Glaring at this new enemy, he hunched his massive shoulders and growled.

“He reminds me of a wild boar,” thought Matsuzo, “with his mean little eyes and thick neck. Why, he’s even pawing the ground with his feet.”

Exactly like a wild boar, the monk made a sudden vicious charge. But Matsuzo was prepared. When the monk was two paces away, the young ronin quickly stepped aside, clinging girl and all, and thrust out his foot. Unable to stop himself, the monk tripped over Matsuzo’s foot, staggered wildly, and ended by crashing into the eel vendor’s stall.

A hoarse scream arose from the collapsed wooden stand, torn canvas and scattered charcoal. The smell of burning human flesh was now added to the aroma of broiled eel. The girl released her hold on Matsuzo and ran to the eel stand. Taking one look at her former adversary, she threw back her head and burst out laughing. Matsuzo found her laughter very infectious, and soon he and most of the bystanders in the street joined her.

It is annoying to be the object of general laughter while one is sitting on a hot grill next to some eels. The furious monk bellowed. He thrust himself up from the wreckage of the eel vendor’s stand and reached for his staff, a murderous weapon tipped with iron.

Matsuzo stopped laughing and watched the approach of the monk with grim satisfaction.

He now had a perfect excuse for drawing his sword.

Meanwhile Zenta had not been idle. He had noticed something which Matsuzo had not, that among the onlookers were two other monks wearing identical headdresses. When Matsuzo reached for his sword, the other two monks hurried forward to the aid of their companion. But well before the first monk had picked himself up from the eel stall, Zenta had already acted. Quickly and inconspicuously, he worked his way through the crowd until he was standing directly behind the two watching monks. He took out a piece of looped cord used by all samurai to tie their wide sleeves out of the way in preparation for action. But instead of tying his own sleeves back, he tied the sleeves of the two monks together.

The monks noticed nothing so long as they walked forward side by side; but when they separated to attack Matsuzo, they jerked to a standstill. Annoyed, both men simultaneously gave a sharp tug. It was the height of summer, and the men were wearing thin cotton kimonos loosely tied at the waist with a sash. At this tug-of-war the man whose sash was less tightly knotted found himself stripped down to his loincloth. The other man’s kimono was pulled off his shoulders, but his sash held tight, and he was left bare to the waist with his friend’s kimono draped over his ankles.

The angry curses of the two monks drew the attention of the crowd away from the drama at the eel stand. When the girl saw the near-naked men, she burst into fresh peals of laughter. “Look at their fat stomachs!” she cried. “I don’t think these monks are very strict about their vegetarian diet!”

One of the monks had finally discovered the cord that was tying the two sleeves together. After trying without success to loosen the tight knot, he whipped out a short, ugly knife and slashed apart the sleeves. Then, knife in hand, he advanced on Matsuzo as the person responsible.

Now that bloodshed seemed inevitable, the crowd fell silent and pressed back, leaving an arena cleared for action. Zenta shook his head gloomily. His hand dropped to his sword and his thumb pressed against the guard, easing the sword up for instant release.

The sound of hoofbeats suddenly broke the silence, and a man at the edge of the crowd cried, “Some soldiers are coming! They look like Nobunaga’s men!”

The crowd quickly drained away. The first to leave were the three monks, who thrust themselves roughly past the townspeople and disappeared into a side street. After his troops had occupied Miyako, one of Nobunaga’s first acts had been to suppress all lawless elements in the capital city.

Zenta grabbed Matsuzo. “We’d better leave, too. We can’t be brought to Nobunaga’s attention as participants in a public brawl.”

But before the two ronin could leave, a voice said, “Don’t go.” It was the girl. Indicating the leading horseman, she said, “I know this officer well, and I shall tell him that you came to my rescue.”

When the officer saw the girl, he dismounted and hurried to her. “Chiyo! I heard that some monks were attacking you. Are you hurt?”

“I only have a few scratches,” replied the girl called Chiyo. “I’m in better condition than my attacker, thanks to the help of these two kind gentlemen.”

The officer turned to look at the ronin. When he saw Zenta, his eyes widened. “Konishi Zenta!” he cried. “Now that I look at the total shambles here, I should have known that it was you!”