Читать книгу Surviving Hell - Leo Thorsness - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Sitting in my office in downtown Minneapolis one beautiful summer day in 2008, I received a telephone call from Tom Steward, head of press relations for the office of John McCain’s presidential campaign in St. Paul, Minnesota. Tom asked me how I would like to meet a recipient of the Medal of Honor over lunch at the campaign office. I said that sounded great.

Arriving at the McCain office in St. Paul, I was introduced to Leo Thorsness. He was holding a small audience around a table in rapt attention. I vaguely recalled Thorsness as a Vietnam veteran who had narrowly lost a 1974 Senate race to George McGovern in the toxic aftermath of Watergate. That recollection proved accurate, but his record contains a few other items of interest.

He is a native Minnesotan, having been born into a farm family near Walnut Grove, and graduated from Walnut Grove High School in 1950. Walnut Grove is now known only as the home of Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of Little House on the Prairie, but it should also be known as the birthplace of the author of Surviving Hell.

Thorsness left Walnut Grove after high school to attend South Dakota State College, where he met his wife in the freshman registration line. In January 1951 he enlisted in the Air Force, and he graduated from pilot school in 1954. He was a career fighter pilot, reaching the rank of colonel and accumulating 5,000 hours of flying time.

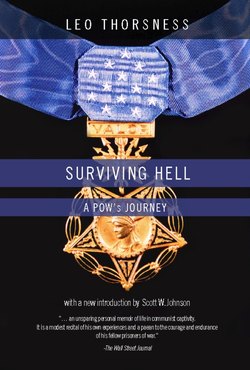

Colonel Thorsness flew 92 and a half Wild Weasel missions over North Vietnam. He earned the Medal of Honor for a Wild Weasel mission he flew on April 19, 1967, eleven days before being shot down. He tells the story of what he calls his Medal of Honor Mission in Chapter 1 of this book, but the Air Force account also makes good reading:

Thorsness, then a major, was “Head Weasel” of the 357th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Takhli Air Base in Thailand. On April 19, 1967, he and his backseater, Capt. Harold Johnson, fought a wild 50-minute duel with SAMs, antiaircraft guns and MiGs. They set out in a formation of four planes. Their target was an army compound near Hanoi, heavily defended. Thorsness directed two of the F-105s north and he and his wingman stayed south, forcing enemy gunners to divide their attention. After initial success at destroying two SAM sites, things turned for the wors[e]. First, Thorsness’ wingman was hit by flak. He and his backseater ejected. Then the two Weasels he had sent north were attacked by MiGs. The afterburner of one of the F-105s wouldn’t light, so he and his wingman were forced to return to Takhli, leaving Thorsness alone to fight solo.

As the F-105 circled the parachutes, relaying their position to the Search and Rescue Center, Johnson spotted a MiG off their left wing. The F-105, though not designed for air-to-air combat, responded well as Thorsness attacked the MiG and destroyed it with a 20-mm cannon, just as another MiG closed on his tail. Low on fuel, Thorsness broke off the battle and rendezvoused with a tanker.

In the meantime, two A-1E Sandys and a rescue helicopter arrived to look for the crewmen. Upon being advised of that fact, Thorsness, with only 500 rounds of ammunition left, turned back from the tanker to fly cover for the rescue force, knowing there were at least five MiGs in the area. As he approached the area, he spotted four MiG-17 aircraft and initiated an attack on them, damaging one and driving the others away from the rescue scene. His ammunition gone, he returned to the rescue scene, hoping to draw the MiGs away from the remaining A-1E. It could very well have been a suicidal mission, but just as he arrived, so did a U.S. strike force and hit the enemy fighters.

But Thorsness’ day wasn’t over yet. Again low on fuel, he headed for a tanker just as one of the strike force pilots, almost out of fuel himself, radioed him for help. Thorsness knew he couldn’t make Takhli [his home base] without refueling. ...

Thorsness quickly determined that he might be able to make it past the Mekong River or even to Udorn Air Base in Thailand, just across the river. He climbed to 35,000 feet over Laos. Seventy miles from the river, his fuel gauge showed empty. He throttled to idle and glided to Udorn; his tanks went dry as he touched down. By giving up the refueling tanker and directing it to the other strike fighter, Thorsness saved the pilot from ejecting over Laos.

It is difficult to comprehend that the heroics recognized by Colonel Thorsness’s Medal of Honor were followed by further displays of heroism approximating the valor he displayed on this mission. When he was shot down by an air-to-air missile in late April 1967, he ejected from his exploding fighter doing more than 690 miles per hour, injuring both knees and sustaining multiple fractures of his back. Like John McCain, he was “tied up” for the next six years. He was captured and held as a prisoner of war in the Hanoi Hilton and several other North Vietnamese hellholes, including the one known as Camp Punishment, reserved for especially “difficult” cases.

His Medal of Honor was awarded in 1969, but was kept a secret so that the North Vietnamese would not use the citation against him and aggravate the conditions of his captivity. As it was, he was tortured unmercifully for his first three years in prison. Upon his capture, he was tortured in interrogation for 19 days and 18 nights, without sleep.

In my meeting with him, Thorsness mentioned to me in passing (as he writes in this book) that he didn’t “break” for 18 days, after which he finally provided something more than name, rank, and serial number. As I sat listening to him, I thought to myself, Someone has to write up this story. Fortunately, someone has. Thorsness himself has done so in this moving book.

At 127 pages, Surviving Hell is brief and understated. It presents itself as a self-help book. “For the past 35 years,” Thorsness writes, “my mind has worked to process what happened.” Through the book, he means to make his experience of use to others: “With the benefit of perspective, I wanted to write a book that would be helpful to people going through tough times.” For more reasons than one, this book deserves a wide audience.

Thorsness calls the ordeal he endured hell, and no reasonable reader will disagree. Thorsness survived. So can you. He states right up front: “Time heals most things, and we are stronger than we think.” Hellish experience lends a certain perspective. “In the 35 years since my release from prison,” Thorsness writes, “I’ve never really had a bad day.”

He documents several forms of hell. Regarding the torture he endured upon his capture, for example, he remarks: “I would say that my 18 days and nights of interrogations were unendurable if I hadn’t endured.” He observes that “[t]here was nothing particularly imaginative about the North Vietnamese techniques. They hadn’t improved much on the devices of the Spanish Inquisition.” Nevertheless, he relates that he received a sampling of the innovations in torture practiced by a team of three Cubans who had been dispatched to assist the North Vietnamese.

He was distraught when he was broken on day 19 of his initial captivity. “I tried to cry. But I was past tears.” Upon his return to his cell, however, he was reassured that everyone who is subjected to such an interrogation “has one of two things happen: either they broke or died—some did both.”

The book is divided into short chapters that may alternately elicit tears and laughter. The mistreatment and degradation endured by Thorsness and his fellow prisoners of war—our fellow Americans—are by turns enraging and heartbreaking. At one point Thorsness relates his discovery that the North Vietnamese essentially left those airmen who had lost limbs upon ejection from their aircraft to die. To the North Vietnamese their burden was deemed to outweigh their potential benefit.

When he reached Camp Punishment, Thorsness writes, his interrogator told him several times: “You must learn to suffer.” Thorsness drily records: “This I had already done.”

The book is also shot through with the black humor that Thorsness and his fellow prisoners directed at their captivity. The humor played a role of its own in surviving hell. The humor appears regularly throughout the book, but in this connection I especially commend Chapters 13 (“Boredom”), 17 (“The Home Front”), and 18 (“Prison Talk”).

Even wives, girlfriends, and the families left behind at home could become the subject of humor. When the prisoners of war finally were allowed to receive brief letters from home, for example, they not only reread them as long as they were allowed to hold onto them, but turned the reading into a group activity. Thorsness recalls from memory the worst-ever letter from home received by one of his fellow prisoners, a particularly tough middle-American farm boy who had survived his original captivity in Laos and deserved better:

Dear Raymond, this has been a bad year. Hail took our crops—no insurance. Your brother-in-law borrowed your speedboat, hit a rock, it sank. Aunt Clarice died suddenly last August. Dad tipped the tractor but only broke his leg. Your 4-H heifer grew up, became a cow, but she died calving—calf too. We think of you often. Mom and Dad.

“There was dead silence for perhaps a minute,” Thorsness relates, as the assembled POWs absorbed the letter:

Finally, someone said, “Ray, read it again, maybe there’s a hidden meaning.” He shook his head. After more encouragement, he read it again. When he got to the part “your speedboat sank,” a POW in the back could no longer hold his muffled laugh. When Ray read, “she died calving,” the snickers turned into open, uncontrolled laughter.

In six years of prison, there was never a more genuine slap-yourthighs, roll-on-your-side laughter. We were in stitches and couldn’t stop. Ray, bless him, realized how ridiculous, how totally inappropriate it was for family to write that letter to someone in prison. He joined in the hilarity.

Thorsness ultimately found the resources to “survive hell” in the four F’s around which he orients his life: family, faith, fun, and friends. (He gave up a fifth F—flying—as a result of his injuries.) Without expressly highlighting the role of gratitude in helping us come to terms with our personal “tough times,” he nevertheless heightens our awareness of it. He reflects, for example:

In my nearly six years in prison, not a day went by when I didn’t think about and hope for freedom. I daydreamed about it, and I night-dreamed about it. I dreamed about it in the indistinct moments that separate sleep and waking. I dreamed about the physical sensation of freedom: how it felt on the body. I dreamed about how freedom might happen: by a daring rescue, by the military defeat of North Vietnam, by a POW exchange.

If Surviving Hell is in part a self-help manual, it is also a straightforward memoir of Thorsness’s captivity as a prisoner of war. As such, it takes its place on the bookshelf alongside such noteworthy memoirs of captivity during the Vietnam War as James N. Rowe’s Five Years to Freedom, Jeremiah Denton’s When Hell Was In Session, Robinson Risner’s The Passing of the Night, Medal of Honor recipient James Stockdale’s In Love and War (written together with Stockdale’s wife, Sybil Stockdale), Medal of Honor recipient George E. “Bud” Day’s Return With Honor, and John McCain’s Faith of My Fathers (written with Mark Salter). The title of this book obviously recalls Denton’s. As a memoir, this book could also be titled Remembering Hell.

Thorsness’s book is extraordinarily understated in its remembrance of hard times. Especially when it comes to his own ordeal, much of the suffering is left unstated or implicit in the text. Consider Thorsness’s reflection on his first three years in captivity: “It was indescribably difficult surviving the first three years of prison, and, if treatment had not improved, I would not have made it through the next three years.”

Thorsness’s story is also representative of the stories of those whose service has brought them the Medal of Honor. Thorsness is one of only five living Air Force recipients of the Medal of Honor. He is active with the Medal of Honor Foundation, seeking to convey the stories of living Medal of Honor recipients to a wider audience. One of the foundation’s projects was the production of Medal of Honor: Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty, a book that depicts and briefly tells the stories of living Medal of Honor recipients.

The text of Medal of Honor was written by the founder and original publisher of Encounter Books, Peter Collier, who donated his services to the project. Collier drew on his experience writing the book for a Wall Street Journal column on Memorial Day 2006, called “America’s Honor.” He noted our inattentiveness to heroes such as Thorsness, and our decreasing ability to understand them. “The notion of sacrifice today provokes puzzlement more often than admiration,” Collier explained. “We support the troops, of course, but we also believe that war, being hell, can easily touch them with an evil no cause for engagement can wash away. And in any case we are more comfortable supporting them as victims than as warriors.”

One reason we have a hard time understanding men such as Thorsness is their rarity. In this book, Thorsness provides a case study of the “great-souled” or magnanimous man at the summit of human excellence of whom Aristotle speaks in the Nicomachean Ethics. If it were not for the example set by men such as Thorsness, we might doubt that such men actually exist.

Aristotle explains (here I am borrowing from the superb translation by Joe Sachs) that the great-souled man is especially concerned with honors and acts of dishonor. The great-souled man, because he holds few things in high honor, is not someone who takes small risks or is passionately devoted to taking risks, but someone who takes great risks. When he does take a risk, he does so without regard for his life, on the ground that it is not just on any terms that life is worth living.

In his Memorial Day column, Collier eloquently explained why we should attend to the story Thorsness exemplifies:

We impoverish ourselves by shunting these heroes and their experiences to the back pages of our national consciousness. Their stories are not just boys’ adventure tales writ large. They are a kind of moral instruction. They remind of something we’ve heard many times before but is worth repeating on a wartime Memorial Day when we’re uncertain about what we celebrate. We’re the land of the free for one reason only: We’re also the home of the brave.

Thorsness’s memoir proves this point several times over. It is a book that can provide comfort and assistance to us in our own hard times. It is also a book that can point the way to a life well lived. In its own modest style, this is a great book by a great man.

—Scott W. Johnson

November 2010