Читать книгу Charles Pachter - Leonard Wise - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

Оглавление“What is the point of reading biographies of artists?” asked Deborah Solomon in her New York Times review (December 2, 2015) of Julian Barnes’s Keeping an Eye Open: Essays on Art. Coral Ann Howells, in The Cambridge Companion to Margaret Atwood, remarks that “biography is the making of pâté from the duck.” Is it possible for an entire life to be contained within a book of a couple hundred pages? How does one write someone’s biography when they’re not even dead yet? Solomon suggests that “the details of a life are helpless to explain the majesty of art.”

So the question remains: Should we try to separate the artist from the art?

What matters, Solomon contends, “are not the despairing childhoods and difficult relationships” — whether a particular artist was altruistic like Cézanne, or plainly cruel like Picasso, or publicity-seeking like Warhol — but “the object that emerged in the end, an object unburdened by life, succeeding or failing on the basis of its appeal to the eye.” Yet, she also admits that “biographies of artists offer us a chance to view a life from all sides, to be moved not only by triumphant masterworks but by the stirring efforts underlying even the supposed duds.”

Jacques Barzun, in his book The Modern Researcher, tells us that “biography gives us vicarious experience.” Whether you admire or revile their subjects, biographies can inspire us, encourage us to dream, and, at minimum, let us see how others handled the trials and tribulations of life.

Meanwhile, in Michel Foucault and Theology, a book by James Bernauer and Jeremy Carrette, Foucault is quoted as saying, “We need biography as we need history, in order to dispel the chimeras of the origin. We use biography for its jolts, its surprises, its unsteady victories and unpalatable defeats.” It is usually argued that the point of a work of art is not to learn about the artist but to have an aesthetic experience, regardless of the artist’s intentions. However, information from an artist’s life can sometimes help us understand the meaning of their art.

Charles Pachter emerged as an artist in a country that was previously inhibited by colonial insecurities, a country that gradually grew into a new era of nationalistic pride and confidence. The Canada in which Pachter has worked all of his life is one that, save for a few exceptions, does not celebrate its living artists. It is also a country with a tight and exclusive arts bureaucracy, one that offers little room for or support of artists that don’t play by its rules. Despite this, Pachter has consistently created works that communicate joy and passion, along with humour and a great pride in Canada. It is a body of work of immense achievement.

When we look at his art, though, few bother to appreciate the articulate genius behind his wisecracking facade, or to think about the psychological burden he has had to endure from years of rejection by government granting institutions, curators, art critics, and members of the art establishment. The works succeed or fail by themselves, of course, but knowing the context in which they were created lends greater resonance to them.

Charles’s struggles to survive and thrive as an artist are ones that he shares with other artists, too. The fracturing of relationships and the forfeiture of any semblance of normal life are common occurrences for many artists. Few readers ponder their sacrifices — the sleepless nights; the years spent alone, painting when depressed, when elated; the self-promoting; the need to be constantly socializing, networking, trying to sell.

Of course, Charles is by no means the only successful self-promoter in the art world. Gustave Courbet was a great painter, but he was also a serious publicity seeker. So was Salvador Dali, and so is Jeff Koons. Andy Warhol was another big self-promoter; he felt that being good in business was the most fascinating kind of art, and that making money is art and good business acumen is the best art.

After decades without any official recognition or support, Pachter began to finally receive acknowledgement for his achievements in the 1990s. One of the highlights of his life was the year he received an honorary doctorate from Brock University in 1996.

The media release stated, “In the 1960s he completed his undergraduate education in Toronto, where his parents hoped he would pass on being an artist and become a doctor.” Finally he had become one.

In his honour, Atwood sent him the following ode:

The Life of Charles

(short version)

There once was a young man named Pachter

in whose life fine art was a factor

He painted and painted

until he was sainted

by an honorary degree for which

we shout congracht[1]

In 1999 Charles became a Member of the Order of Canada at an elegant ceremony in Rideau Hall in Ottawa. The award was itself a great honour, of course, but the whole thing was made sweeter by the fact that Governor General Adrienne Clarkson, an old friend, bestowed it on him. She congratulated Charles before the crowd, and then, knowing how much the award also meant to him, said, “I’m so glad you were able to bring your mother.”

Thirteen years later he was promoted to Officer of the Order of Canada. Letters of congratulations arrived from Shirley Thomson, head of the Canada Council, an organization that had turned him down a dozen times for a grant, and Matthew Teitelbaum, the director of the Art Gallery of Ontario, an institution that has yet to purchase any of his work.

In 2009 Pachter received an honorary doctorate from OCAD University, and a year later another one, this time from his alma mater, the University of Toronto. Following Pachter’s acceptance speech, Chancellor David Peterson told him, “Charles, you gave the best speech I have ever heard at a commencement.”

How I Met Charlie

In September 1969 I was at a friend’s house in Rosedale. I bumped into Charlie Pachter, a twenty-seven-year-old artist who’d already had two solo exhibitions. He was talkative and amusing, attracting attention with his wit and his storytelling. At that time he was living in a house he had just purchased on Shaw Street, where he was building a printmaking studio.

His creative enthusiasm about everything was infectious. Somehow we became friends. Over the next forty-seven years I got invited to his parties and exhibitions, met his friends, and watched collectors acquire his paintings. My wife, Sandy, and I were also guests at his winter home in Miami Beach and at his summer home in Orillia.

What’s he like? Well, for starters, he’s generous, loving, non-judgmental, sensitive, articulate, quixotic, cheeky, mercurial, capricious, and roguish. He’s also self-centred, and has a tendency to tell tasteless jokes — though he does so with great timing. A natural entertainer, he likes working a crowd, and he is a gifted raconteur, a historian, and an outstanding public speaker. He’s also an insightful architectural designer and developer, entrepreneur, promoter, bargain hunter, and negotiator. In short, he’s a Renaissance man. But the most remarkable feature about him, according to those who know him well, is that his kindness is boundless. His generosity is unsurpassed, whether it’s the artworks he gives to charities or the use of his home and studio that he freely provides for fundraising events.

Paradox defines him:

1 His studio is messy, and his clothes are often paint-spattered, but his living space is spotless (thanks to Guida, who has been his faithful cleaning lady for years).

2 He’s happiest when he is surrounded by people, and he’s happiest when he is by himself.

3 He’s a monarchist who loves royalty, yet he delights in satirizing them.

I was given the opportunity to write this book after I dropped in on Charlie a few months ago and he asked, “What are you doing these days?”

Having retired as a lawyer, I mentioned that I was now writing memoirs for various individuals. That prompted him to phone Kirk Howard, publisher at Dundurn Press, to inquire, “Are you still interested in publishing my biography, because if you are I may have a writer for you.”

Kirk’s response was simple: “If you want him to write it, then so do I.”

And so began the process of my researching Charlie’s life.

One of the things that made this easy (and difficult) is the fact that Charlie is a pack rat. He keeps a copy of almost everything he’s done, said, or thought, including records of almost everyone he’s ever met. So there was a great deal of material to look through.

His papers are now in the archives at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto. I spent my first few weeks working on the book there, poring through seventy boxes of Pachter lore, from his Grade 1 report card, to letters from camp that he wrote to his parents, to the voluminous correspondence between him and Margaret Atwood, whom he has known since they were teenagers.

I had the great pleasure of interviewing fifty of his friends, some of the most interesting people I have ever met. I particularly enjoyed the mischief of John Fraser, the erudition of Michael Marrus, the graciousness of Marcia McClung, the wit of Rosie Abella, the thoughtfulness of Rick Salutin, and the penetrating insights of Margaret Atwood. I chatted with eighty-nine-year-old Norman Jewison and was treated to lunch by philanthropist Nona Heaslip.

I watched Charlie give a funny, informative speech to one hundred elderly monarchists at the Canadian Royal Heritage Trust dinner at Wycliffe College in the University of Toronto about the creation of the Town of York by Ontario’s first lieutenant-governor, John Graves Simcoe.

A day in the life of Charlie, assuming you can keep up with him, entails following him on Dundas Street as he heads for Dim Sum King, one of his favourite Chinese restaurants, where the waiters call out to him “You VIP!” and where everyone seems to know him.

Being at home with him is like living in a circus. The phone rings, the email pings, the doorbell dings, and people come and go. An emerging artist asks him for a critique of his work, a lady solicits a donation of his art for her charity, and another wants to reminisce about the old days on Queen Street. And on it goes. He donates his artworks to fifty charities a year, gets fifty emails a day, spends three hours a day on the computer, and has 4,500 followers on Facebook.

Nowadays, at age seventy-four, Charlie is still on a roll, selling his work to serious collectors, and, totally unexpectedly, finding a life partner. He has built a second home and studio in Orillia, and he envisions a major cultural arts campus there on the site of the former Huronia Regional Centre. As many have noticed, he’s never been happier.

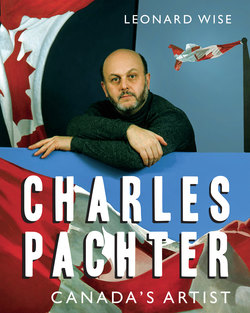

Welcome to Charles Pachter: Canada’s Artist.

Charles Pachter exhibition in the Throne Room of the Charterhouse, London, August 2016.