Читать книгу Cult Sister - Lesley Smailes - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеI am a people person. I love the sense of belonging that comes from being part of a group, a greater whole. Community. ‘You should have been an impala, you are so gregarious,’ my Granny Precious once told me. She was right. So was my Nanny Goodness. With me tied to her back sitting straddled across her ponderous buttocks, she told my mom: ‘This one – her name is Thandabantu!’ That means ‘the one who loves people’ in isiXhosa.

My friends have always been important to me, especially when I was a teenager. We were rebels, wild and free, smoking joints, gate-crashing parties and getting sozzled at popular drinking spots. Like strands of thread on a poncho fringe, we joined our lives. What we had in common was the ‘jol’. The high. The experience. The strangeness of growing up in our apartheid-censored country of the late Seventies and early Eighties.

Patti Smith, Talking Heads, The Cure, Rodriguez – music helped us define ourselves and make sense of our world. Sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Are You Experienced? Confused and full of wow-wonder, the lyrics of this Jimi Hendrix song became my personal anthem.

The way I saw it, rules were there to be broken. Even now at age 52, though wiser and more circumspect, I am still an unconventional, boundary-pushing person. This has sometimes landed me in a whole lot of trouble, but it has also opened the door for some incredible adventures, leaving me with my abundance of stories.

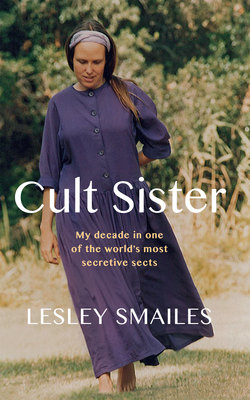

This one has been painful to remember. How do I explain that for ten long years I was a member of one of America’s most conservative and secretive cults? That for most of the Eighties I dropped out of the world, changed the way I dressed and spoke, bought into a system of beliefs in which women are completely subservient, married a man I barely knew and had three children with him – all of this while crisscrossing the United States, camping in the woods or squatting in unoccupied buildings that often had no electricity and running water, and eating food from garbage bins. I know it sounds crazy, but I did it. For a whole decade I turned my back on almost everything I knew to be part of a religious group in which adherents spurned almost all modern comforts and behaved as though they lived in olden times.

We did not have an official title, although we referred to ourselves as ‘The Church’ or ‘The Brothers’. Others called us ‘The Bicycle Christians’, ‘The Jim Roberts Group’, ‘The Brethren’ and some ‘The Raincoat People’, probably because of the long garments the brothers wore. The less imaginative called us names like ‘The Dumpster Divers’ and ‘The Garbage Eaters’. Many people would be revolted at the thought of eating ‘rubbish,’ but to be fair the items we procured were generally more than edible and I can’t say I lacked for sustenance. Nor was I made ill by any of it in my years of scavenging for what was freely available. In fact, I reckon I probably ate better than the average American.

One could find anything in dumpsters, it seemed. If a bakery advertised fresh bread, then day-old loaves were thrown away. If cans had even the slightest dent, they were tossed, if fruit was a little bruised or banana skins brown, out they all went. When a bottle of juice in a crate broke, no one cleaned off the broken glass from the remaining sticky bottles – the whole crate just landed up in the dumpster. Anything that reached expiry date was discarded. All goods that were in any way damaged were dumped. There was a cereal factory that threw away hundreds of boxes of All Bran Flakes because they contained too many raisins. We once found almost twenty litres of organic honey turfed out by a health-food distributor because it had crystallised. Huge blocks of cheese were trashed because of a bit of mould. I could go on and on.

If we needed anything we just went to the back of the shop that sold it and there was a good possibility that it could be found in the trash. The Brothers called this ‘checking stores’.

I could go for months with only five dollars in my wallet and not have to spend it. I neither went hungry, nor paid rent, although I lived in many different houses spanning the whole of the States. We ‘checked stores’, found things, traded, bartered and lived by faith. There is a scripture that says ‘out of the waste places of fat ones shall strangers eat.’ This really applied to us. Because we got almost everything for free, we didn’t need jobs and that allowed us to focus on what was really important. Our main aim was to talk others into forsaking everything and joining the Church. We used the scriptures to manipulate them into abandoning their families, their jobs, education and lifestyles, encouraging them to drop out of society and be ‘separate from the world.’

We were ‘fishers of men’. I was really gung-ho about this aspect of my discipleship. I can be a very persuasive saleswoman when I set my mind to it. During my years as an ambassador for the Church I had a profound effect on quite a few lives and was successful in talking a number of people into joining us.

Members of the church were constantly on the move, our locations a secret to keep ourselves from being found by our deprived families and friends. I don’t think we ever put ourselves in the shoes of the traumatised relatives who were being ‘forsaken’. We referred to them as ‘flesh relations’ and arrogantly dismissed their grief at being abandoned as ‘worldly sorrow’.

‘Cult’ sounds like such a harsh word. It instantly conjures up images of weird and dangerous sects such as the Children of God, the Moonies and the Branch Davidians. We weren’t as far-out as these groups. But in many ways, although I would never have admitted it at the time, we were a cult. A fairly benign cult but a cult, nevertheless. A man named Jim Roberts was our leader and we based all our actions on his interpretation of the scriptures in the King James Bible. We referred to him as ‘Brother Evangelist’, or ‘the Elder’. He called the shots. There was to be no questioning, no criticism, no complaints. What he said went.

How could a rebel like me buy into this? Ironically I think it was the rebellious side of me that found the group so fascinating. They were just so darn radical. It felt romantic, like I was joining a gypsy caravan. We crisscrossed America, drifting between towns and cities, setting up home in abandoned buildings. When we arrived in a new city, the brothers would scout out empty houses and apartments, then go to the deeds office to find the owners’ contact details. They would then phone and ask permission for us to occupy their properties. Often landlords were just grateful to have someone living in these buildings rather than having them stand vacant at the risk of being vandalised. So in return for us doing a bit of light maintenance, we were often allowed to live rent free.

It was only years in that disillusionment set in. My rose-tinted glasses slipped and the cracks started to show – but by then there was no turning back. I was married and had three children. Where would I go? The Church was my life. I was Sister Lesley.

We were hardcore, almost militant. Our Church made most others seem wishy-washy. On fire, we burned with zeal, often at the expense of our own compassion. So how does a girl from a small town on the southern tip of Africa get involved in all this? Good question.