Читать книгу Three Bright Pebbles - Leslie Ford - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5

ОглавлениеIrene and Major Tillyard were standing in front of the bright wood fire burning behind the great old polished brass andirons, in what had been the dining room of the original house but was now a sort of family sitting room, with soft chintz-covered chairs and sofas instead of the formal period pieces of the drawing room across the hall—lovely but not particularly comfortable with its delicate Sheraton sofas and straight-backed fireside chairs. They were still talking about the farm, and they stopped abruptly as I came in.

Irene held out her hands to me.

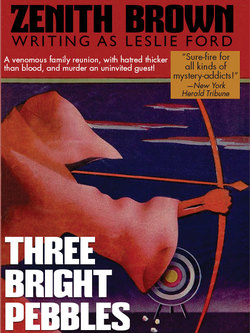

“Oh, darling, it’s really so nice to have you here—like old times!” she said, smiling. All trace of annoyance and petulance was gone, like a cloud in April. “And I do hope this dreadful weather clears up, because in the morning we’re going to shoot a full Columbia round!”

I’m afraid I blinked, because Major Tillyard smiled.

“Archery, Mrs. Latham,” he said.

“Then that lets me out,” I said—adding to myself, in the expressive jargon of my younger son, “I hope I hope I hope!” Archery is not one of my favorite sports.

“Why Grace, aren’t you awful!” Irene cried. “We really need you! And besides, my dear, it’s awfully good for the figure!”

“I’ll stick to a horse, if you don’t mind.”

Irene shrugged her slim bare shoulders. She certainly, I thought, didn’t look like fifty-five . . . or act it, I added to myself as she said, “Oh, of course, Grace, if you want to spoil—”

Major Tillyard poked the fire a little abruptly, and she broke off.

“Of course you’ll come in, Grace—don’t be silly,” she laughed.

Major Tillyard put down the fire iron. “I think I’ll be getting along, Irene.” He took her hand. “I’m sorry about tonight. Don’t let it upset you, will you, my dear.”

He shook hands with me, and he and Irene moved toward the door. I looked at his broad straight back and thick iron-gray hair, thinking that Irene showed remarkably good judgment at times, and sat down by the fire. As I did I felt a sudden draft on my cheek, and glanced around at the window. And I started, not sure I wasn’t definitely seeing things.

A perfectly mammoth creature had pushed aside the curtains and walked in, blinking two light blue eyes through a ridiculous fringe of long dirty gray hair. I don’t know what, at first sight, I could have thought it was, because quite obviously under the three bags of curly wool it was a dog. He grinned very amiably and wagged his tail. Irene and Major Tillyard in the door both turned, and Irene said, “Oh, there’s Dr. Birdsong,” which seemed a little confusing to me until almost immediately the curtains parted again and a very tall man came in.

He was even bigger than the dog, and looked rather like him, in a slightly different way. He didn’t have as much hair, and it wasn’t gray, except a very little near the temples. His country tweed jacket was rough and baggy, with chamois patches at the elbows, and was definitely for use and not beauty, and his high laced boots and riding breeches were streaked with mud. His hands were enormous, and yet gave an impression of being extraordinarily mobile and sensitive. His eyes, like the dog’s, were a light pale bluish-gray, his face was burned almost black and looked more like corrugated iron than skin. And somewhere about him there was an astonishing quality of detachment, in his eyes probably—as if they seldom looked at the things close by.

He didn’t smile as he strode in through the window, and the dog looking up at him, and apparently realizing that he had been a little previous, took the grin off his face, walked over to the fire and lay down with a solid comfortable grunt, divorcing himself from whatever unpleasantness was about to ensue.

“There’s a tree down in the road, Sidney. You can’t get your car out. I thought if you were ready I’d pick you up.”

The smile died on Irene Winthrop’s face. Whatever she’d started to say went with it. Her lips tightened.

“Why doesn’t Mr. Keane move the tree?” she said sharply. She reached for the needlepoint bell pull hanging from the carved overmantel. “I’ll send—”

“Mr. Keane has been fired, Irene,” the tall man said curtly.

Irene’s delicate face flushed. “That’s silly! There’s no reason for his letting things go just because—”

Dr. Birdsong—I took it that he, not the dog, was the doctor—jammed his ancient felt hat on his head and interrupted her brusquely.

“Some day you’ll find you can’t have your cake and eat it too, Irene.—If you’re ready, Sidney. We can take your car to the tree—mine’s on the other side.”

He strode out. The dog, who apparently had been quite sound asleep, got up and ambled after him.

Irene held out her hand. “Good night, Sidney.” She closed the door sharply, came back to the fireplace and stood looking down into the yellow flames. She was very angry.

“If they think they can bully me into letting that man stay on, they’re wrong,” she said quietly, after a long time. “I must say I can’t understand Sidney Tillyard. He acts as if Alan Keane was completely in the right, stealing from the bank. He wanted to take him back, at the time—goodness knows what would have happened if his Board had let him have his way. Just because I’ve taken his advice from time to time is no reason for him to think he can dictate my affairs.”

“Is he trying to?” I asked. He had seemed to me amazingly patient, that night.

She drew a deep breath and shook her head. “He thinks I ought to give each of the children an allowance, and let them live wherever they please . . . including Mara, for heaven’s sake, who obviously isn’t capable of taking care of herself. He thinks it’s a mistake to divide the estate, and that if I give Rick his share now I’d have him back on my hands in two years.”

“I thought you were going to give Rick an allowance when he married,” I said.

“I certainly had every intention of doing so, until he flew in the face of all my . . . my prayers, and married a total stranger, that he picked up heaven knows where!”

“She seems to me like an extremely nice girl,” I said.

She looked at me with a slow astonished expression on her lovely face.

“My dear Grace, how can you say such a stupid thing? Anyone can look at her and see she’s nothing but an adventuress. And this business tonight certainly proves it. You didn’t see the look on Dan’s face when he saw her! At the table in his own home, his own brother’s wife, was certainly the last place in the world he expected to run across her again.”

I smiled. That part of it was certainly true.

“And I’m glad Rick’s eyes are finally opened,” Irene went on. “I’ve made it—I think—perfectly clear to him that as long as he’s married to her, he needn’t expect anything from me. I think he sees now what a fool he was not to be the one to marry Natalie.”

“Do you think Dan is going to marry her?” I inquired.

“Of course. He’s got to.”

“Why?”

She came over and sat down in the deep love seat beside me.

“Grace . . . the reason I sent for you this week end is this.—My husband was your husband’s own first cousin.”

I nodded.

“When he died, Grace, he left his estate entirely to me, except that at my death, or before if I chose, and if the need arose, three-fourths of one quarter of it was to go to his sister’s child. The other one-fourth of that quarter was to go to your two children.”

I looked at her in complete surprise. It was the last thing in the world I should have expected.

“And . . . Natalie is that sister’s child.”

“You mean she’s Dan’s cousin?”

She made a quick impatient gesture.

“That doesn’t make the least difference—she takes after her father and Dan takes after me, so it’s exactly as if they weren’t at all related.”

It seemed very convenient, and definitely, as Dr. Birdsong had said, of the eat-your-cake school.

“Does she know about this—the will, I mean?”

Irene shook her head. “The point is, however, that she’s an orphan, and a very nice girl, and a really quite beautiful girl . . . and if one of the boys marries her, I won’t have to divide the estate now . . .”

She got up abruptly.

“At least that was my idea this morning!”

Her slim white hands moved in a limp, weary gesture.

“I don’t know, now. I don’t suppose you realize how awful that scene at the table was, with Rick and Dan and Mara at each other’s throat, hating each other . . . and me. Of course, nobody understood but Sidney and myself that Rick is bitterly opposed to my marrying. He’s always hated Sidney. I think if Sidney hadn’t been in the bank Rick would have stayed on and perhaps amounted to something. Perhaps if I gave him his money now he’ll still do something. Sidney’s opposed to it, but it’s because he doesn’t understand Rick.”

She leaned her head on the mantel and stared down into the fire, the flames lighting her filmy crimson gown, making the shadow of her body seem too light and fragile to hold up against her strident warring family.

“I wonder if any other mother ever felt the way I do, or if I’m nothing but an unnatural beast,” she said quietly, after another long pause. “But Grace . . . sometimes I almost hate Rick, and . . . Mara. And I know they hate me.”

Her voice had sunk almost to a whisper. Outside a gust of wind buffeted the windows, a shutter banged. Above it came that dreadful shrill shriek. I got up abruptly.

“You’re being stupid. Irene,” I said, rather brutally, I’m afraid. “You’d better go to bed and forget tonight.”

I went to the window to close it, and for some reason that I wasn’t quite aware of I drew the curtains aside and looked out. Someone slipped quickly behind one of the white fluted columns, but not quickly enough to escape the shaft of light falling on her auburn hair. I let the curtains fall . . . wondering what difference it might make that Natalie Lane had heard all this too.

I drew the window down and came back to the fire.

“Who was the man with the dog?” I asked.

“That’s Tom Birdsong,” she said dully.

“Is he a doctor?”

“Among other things. He doesn’t practice—nobody knows why. He’s the local man of mystery.”

I started out.

“Please go to bed, Irene.”

She kissed me lightly on the cheek.

“You probably think I’m a very wicked woman,” she said softly. “Good night.”

It wasn’t, I thought as I went up stairs, the old pine banister satin-smooth under my hand, as much a matter of thinking that Irene was wicked as of thinking that since I’d seen her last she had really changed incredibly . . . or that perhaps I’d never really known her, never had seen her before in a situation that was anything but rather charmingly casual—certainly not one as fundamentally emotional as this night’s.

I went to bed and turned out the light, but I didn’t go to sleep. Even if it hadn’t been for the wind moaning in the old chimneys and tearing like dead hands at the wooden shutters, and the eerie screaming of those birds, like souls lost in hell, Romney was still too full of ghosts for me, ghosts of my own dead past. I must have dropped off at last, however, for I’m sure I woke up hearing hushed frantic voices outside my door in the hall.

“You can’t leave now, you can’t! Don’t you see it’s just what they want you to do?”

It was Mara’s voice, urgent and passionate.

“Cheryl—you can’t go!”

“But I’ve got to go, to-night! You don’t understand, Mara! A horrible thing has happened . . . please let me go, I tell you I’ve got to!”

“But you can’t! The tree’s down over the road—you can’t walk, you can’t stay in the village all night!”

“But you can phone Alan—he can take me to Washington. I’ve got to go, Mara.”

There was a long silence. I heard steps on the polished pine floors then, and in a few minutes the tinkle of the country phone. I looked at my clock. The hands pointed to twenty minutes past one. I lay there as long as I could without going quietly out of my mind, and got up. However bad the situation was, it seemed utter folly for Cheryl Winthrop to go barging off into the night in Alan Keane’s open car . . . it would only give Irene and Rick another stick to thwack her with, and it wouldn’t help Dan.

I put on my dressing gown and slippers, opened the door into the hall, and went along the hyphen corridor to the main upstairs hall where the phone was. The receiver was hanging down, but neither of the girls was there. Then as I stood there, wondering what to do, I heard low and bitterly intense voices below. I looked over the pine rail. Down in the lower hall, cowering in a corner, was Mara Winthrop, in front of her, a riding crop in his raised hand, was Rick. His voice was like a hissing madman’s: “Where is she, damn you! Tell me where she is, or I’ll—”

Mara’s answer was a strangled terrified sob. “She’s gone, out there!”

For a moment I stood there, not knowing what to do. Then I saw, quite suddenly, a figure standing in the shadow of the landing just below me, watching this as I was watching it, and my blood froze with horror. It was Irene Winthrop . . . just standing there, not raising a hand or saying a word to save her youngest child in that moment of abject mortal terror. My hands on the dark wood rail were cold and shaking like a leaf. Below me then I saw Mara sink down on the sofa and sit perfectly rigid, staring white-faced at the door that had slammed on her brother’s back.

Irene hadn’t moved. I stood there for a moment, frightened and angry—angrier, I think, than I ever remembered being in all my life. Yet I knew that if I made a scene it wouldn’t help—anybody: Mara, or Cheryl, or Dan. I could, however, keep something pretty terrible from happening to Cheryl. I thought of that riding crop and of Rick Winthrop’s face, convulsed with rage.

I turned as silently as I could and crept along to the other wing, the dining room wing where Dan’s room had always been, and opened his door. In the dim light I could make out the great fourposter bed and its blue resist print curtains. I could see Dan’s bags still unpacked on the rack. I ran across to the bed and put my hand out to wake him, and touched the soft cool linen sheet still folded neatly back.

My heart stopped dead at a sudden wild shriek outside, and beat again as I realized that it was only one of Irene’s fancy buzzards. My knees were shaking and my hands were icy, and I don’t know how long I stayed there, just standing by the bed, afraid to go back for fear of meeting Irene. I had a profound conviction in my heart that she would make Mara, and Cheryl, suffer for that night . . . so charmingly and delicately that no one but they would know what was happening.

Just as I was gradually realizing that I had to go back, I couldn’t stay here, I heard slow cautious footsteps coming down the hall, something in them so secret and stealthy that without fully realizing what I was doing I slipped behind the tall painted screen in the corner. I heard the door close and the latch uncatch, and a match strike. Looking out between the sections of the screen I saw Dan Winthrop go very quietly to the window and pull down the blinds. Then he took off his shoes and went into the bathroom and turned on the light. I saw him look in the mirror. A long streak of blood trickled down from a cut above his right cheek bone. He mopped it off with a cleansing tissue and painted it with iodine, and examined another cut on the side of his mouth. Then he came back into the room, took the pajamas off his bed, went back into the bathroom and closed the door.

I got back to my own room . . . with a feeling of considerable satisfaction at the idea that if Dan had been marked up a bit, Rick Winthrop was probably unrecognizable.

It was half-past eight when I went downstairs the next morning. Breakfast at Romney is served English fashion, in the summer, on the terrace of the dining room hyphen, overlooking the lawns stretching down to the Potomac. As I came down the wide staircase it seemed incredible that it was less than eight hours since I had seen Mara cowering there in the corner, her brother’s upraised crop, her mother watching, detached and impassive, from the landing by the grandfather clock. The hall was quiet, a fresh breeze from the river came through the front door and out the garden door where Dan and I had come in. It was the cool airy silence of a summer morning in the country, before the day’s life begins and the sun becomes hot and drowsy. A humming bird hung motionless like a jewel in the white wisteria on the garden porch, a wasp nosed at the copper screening on the door.

The old rubbed pine made the hall dim and shadowy inside. I pushed the screen open and stepped out onto the pillared portico, and stood looking down at the green lawns sloping to the glistening waters of the river, almost blue under the clear cobalt sky, and the white urns full of brilliant flowers, and the Italian marble balustrade and benches, drenched with sunshine, that marked off the formal gardens on each side of the long dark alleys of box; and I caught my breath at the loveliness of it. The night, and the storm, and that passionate scene at dinner, were a nightmare—the wind whipping the cedars and the box, the buzzards in the oak, were as unreal as remembered pain. My heart rose inside of me with a sensation of almost physical release . . . and dropped again as suddenly, out of all this loveliness and light and sunshine came that horrible scream again.

I turned my head, hardly knowing what I must see. There parading majestically out of a tiny domed and pillared temple of love set in a crimson sea of roses, came a long troupe of peacocks, strutting the living beauty of their coverts, spread like great jeweled fans above their soft iridescent breasts. I watched them move sedately across the garden, their trains spread, glittering magnificently, a shimmering glory in the sun, to where an odd-looking woman in a wide straw sombrero was sprinkling corn on a marble rose-colored balustrade and calling them in a strange high-pitched voice.

I turned quickly toward the terrace, a quite sheepish flush rising to my cheeks. The glamorous entourage parading through the sunlit flower-decked lawns of Romney made the fantasy of the night an even madder child of my disordered brain. I wondered with some amusement even if the rest of the night was also a horrible imagining: Cheryl’s flight, Mara cowering under the upraised crop, those tell-tale cuts on Dan’s face.

I stepped out on the terrace, and stopped dead. Cheryl Winthrop was sitting at the table, in a blue backless tennis frock, her warm gold skin unbelievably lovely under her thick wheat-gold sleekly waving hair, her eyes as blue as hyacinths, her brown legs bare except for short white socks, her feet in stubby woven grass slippers. And beside her in a Lincoln green archery costume with a peacock feather in her hat, and looking very gay and lovely, was Irene.

“Darling—good morning!” she cried. “I’m so glad somebody can get up in the morning! Do hurry and have a bite of food, and then come along to the range. Cheryl’s not going to shoot, so you really must.”

I steadied myself against the walnut hunting table and poured myself a large cup of coffee from the fluted Sheffield urn. I must, I told myself, be quietly losing my mind. I was convinced of it a minute later when Irene said, “There comes Mara!” and in Mara came, dressed in tan mud-spattered jodhpurs, her jodhpur boots wet and muddy too, her yellow shirt open at the neck, her dark eyes shining, her pale cheeks flushed. She tossed her hat and crop and a yellow glove on one end of the table and sank down in her chair. Then she sprang up again.

“Let me get something for you, Grace. Kidney stew—ham and eggs? Did the peacocks keep you awake all night? I think they’re ghastly, but you get used to it. They’re only vocal once a year—mating season.”

I shall never know how I got through that breakfast, though it didn’t take long, Irene was waiting with such marked impatience for me to finish. She chattered gaily along like a bird among the apple blossoms while Mara and Cheryl ate in silence. When I got up she took my arm, and we went through to the hall and out on the back porch. I glanced up at the spot where she had stood silently looking on at that scene between Rick and Mara. It seemed utterly incredible.

We went out onto the porch.

“Dear, dear, look at that!” Irene cried suddenly. “One of my best bows!”

Lying at the edge of the porch was the bow Dan had fallen over. It’s shaft was broken, the string tangled and snapped at the servicing.

Irene picked it up. “You wouldn’t think these things cost money, the way they’re treated,” she said irritably. “Young people simply haven’t any sense about things.”

She tossed it back on the stone flagging and held up her arms suddenly to the morning, her annoyance over the broken bow completely vanished. “My dear—isn’t it divine! Do come along!”

We crossed the oyster-shell drive, toward the big target that my lights had picked out in the driving rain the night before. It was glistening in the sun now, and a peacock was perched on it, exhibiting the glory of his outspread train to a crowd of gray little peahens.

Irene waved her arms. “Isn’t he lovely!” she cried.

The cock sailed slowly down, alarmed but dignified, as Irene hastened down the green stretch. The sun glistened on the raindrops caught in the tiny cups of the box leaves. I saw it glistening also on some little glass pebbles lying in the close cropped grass not far from the target. I bent down to look at them, they looked so like diamonds fallen there; and as I did so I saw Irene stop suddenly, ahead of me, and heard her give a strange strangled cry, so frightening that I stopped myself, bent halfway to the round. She ran quickly past the target then, toward the box hedge that formed a back drop for the range, stopped again and stood perfectly rigid, staring down at something on the ground.

I straightened up and stood for an instant staring at this odd pantomime. Then, still rigidly poised there, one hand out in front of her as if to ward off some terrible sight, she moved her other hand in an almost mechanical but so imperative a summons that I ran toward her.

Lying huddled at the base of the box hedge was Rick Winthrop, and a slender, feather-tipped shaft was buried in his throat. A stream of blood had trickled down, dyeing his white coat an ugly brown, and dried along the white folds of his collar.

I stood there for an instant, as petrified with horror as Irene Winthrop. Then I felt my eyes moving back, almost automatically, to the golden ball of the target. The arrow that had been there last night, that Dan and I had seen in the beam from my headlights as we rounded the white oyster-shell drive, was gone.

It seemed to me a thousand years that my eyes had to journey from the empty gold back to the inert figure huddled under the box, and at the feathered shaft stained with blood, to realize that it was an arrow, to understand that Rick Winthrop was dead. It seemed a long time too that we stood, his mother, all the jauntiness gone from her archer’s suit of Lincoln green, and I, staring down at him. I didn’t see as much as simply know that her hand was moving out to touch that arrow. As it closed on the green and yellow crest I felt something cold and wet and alive touch my own trembling fingers.

I couldn’t move my hand, or could hardly look down, without forcing myself to do it. When I did, I was looking into a pair of pale, almost white eyes, very alive and strange, behind a fringe of long curly gray hair.

“It’s Dr. Birdsong, Irene . . .” I managed to say.

“Oh, my God, no! No!” she whispered frantically. Her sharp red nails were buried in my arm.